This article originally appeared in the February 1988 issue of SPIN. In memory of Tony Bennett, who died on July 21 at the age of 96, we’re republishing it here.

Tony Bennett is cool.

I have felt this way since the early sixties. Sinatra was hip, but Tony was cool. He was a swinging singer. He was a rocking role model. He was a hip cat. His bow tie looked good undone.

When I was about 15 I went to a concert downtown by myself. At the time I thought I was the only white person there; I was definitely in a minority situation. When Nina Simone came out in Afro regalia and started talking black power, I got scared, but I remained cool. I was there to see Dizzy, Cannonball, Jimmy Smith, Dinah Washington, and Nina Simone too. I decided I was just going to stay put. I figured, fuck it, I’m 15. I didn’t fuck up the blacks. Hey, I’m on their side. I’m a hip cat. I’m staying. And it was cool.

My friends and I were cool and we knew that Ray Charles was seven to the eleventh power cooler than Peter, Paul, and Mary. If anybody asked me who my favorite rock group was, I guess I’d have said the Coasters or Major Lance. I knew I was living in a classical period. And I knew that Tony Bennett was as cool a singer as Mel Torme, if not more so, and good-looking too. Tony Bennett was cooler than Peter Lawford, Jack Kennedy, Joey Bishop. He was like up there with like Caroline Jones, Ernie Kovacs, or Steve Allen.

To me Tony Bennett was always a great jazz singer and a serendipitous cat. The fact that he sang a song about San Francisco is, I think, entirely extra, gravy, lagniappe, the frosting on the cake.

He was a role model of white cool. He was one of our few heroes who never acted like a jerk. Now I know it’s because Tony Bennett always wanted to be an artist first, and to lead “The Good Life” second, and the money and the hype were like secondarysville, man. He knew where it was at because he was with it. The cat dug to blow.

Some years later I started listening to Tony Bennett again. Columbia Records issued a package of some rare vocal sides, Singin’ Till the Girls Come Home, including unreleased jazz sides with Stan Getz, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Elvin Jones. Wow. It swings in perpetuity.

Then in ’87 a big double LP appeared: Tony Bennett, Jazz. Alright. More of the same: remarkable sides of the singer as a musician among musicians. And what musicians: the aforementioned plus Count Basie, Art Blakey, Nat Adderley, Milt Hinton, Joe Newman, Zoot Sims. Like wow. Play it again. And then came the new one, Bennett/ Berlin, Tony doing all Irving Berlin, the way Irving Berlin is supposed to be done: right. With flawless orchestration and great playing and a little help from cats like Dexter Gordon.

I went to see his show.

It was a great show. The whole family had a great time. First Tony gets down with his trio. Then a huge string orchestra levitates from the cellars of Radio City and it’s Tony with jazz trio and serious strings doing the great songs. Then the Diz comes out and blows and sweats and the joint is jumping. Yo, that’s show business.

I took the release of Berlin and this concert as an opportunity to interview my old role model and see how he stacked up.

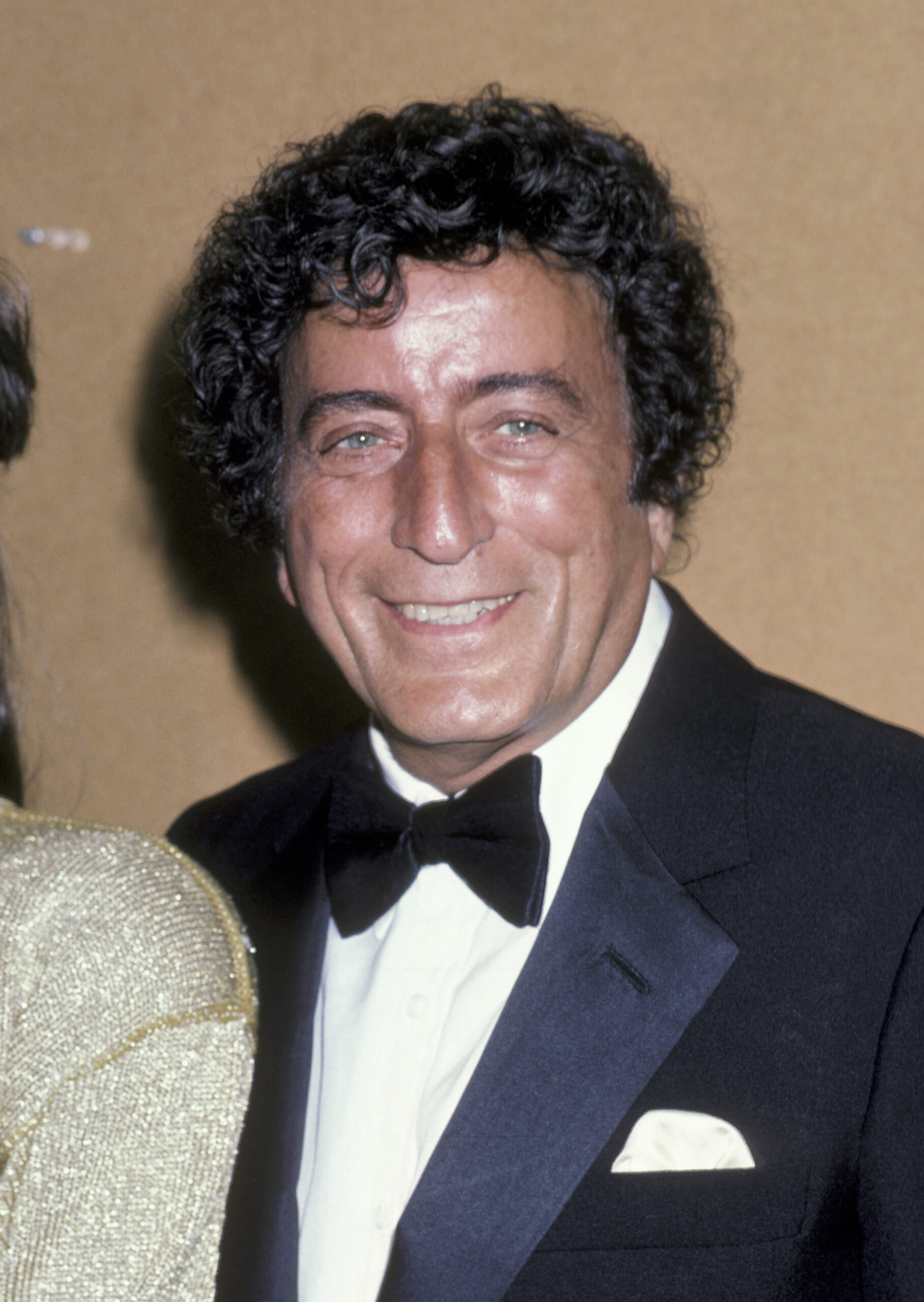

I found him totally solid and down by legal precedent. He was living in the moment, checking it all out. He looks incredibly young for somebody who hit it big in the fifties. When I saw him on-stage, I wondered if he dyed his do, but up close I saw the few white hairs and realized that it was either natural or a very expensive job.

Tony Bennett: Having this Berlin album out is really exciting. I’ve been getting rave reviews on it and that’s fantastic. I’ve never seen anything like it. There’s jazz and there’s pop. But this is being accepted everywhere, even by people who are not really into jazz or pop.

SPIN: But your career has sort of spanned a lot of categories. You’ve been successful as a jazz singer and a pop singer.

Sinatra taught me that years ago. He was very helpful to me when I first started. He gave me some good suggestions and one of the things he always mentioned was: “Stay unpredictable. Don’t be predictable. You might go good for four or five records, but then the ax falls on you if you’re just doing the same old thing.” So you have to do a lot of footwork. You have to be flexible and show up unexpectedly and surprise everybody. It’s an interesting game. The whole game with me is longevity. I’ve been doing this 35 years and I’ve been through every phase of the recording industry. I’ve gone from 78s to 45s to hi-fi to stereo to quadrophonic to digital.

I was amazed when you said during your show that you had released 89 albums.

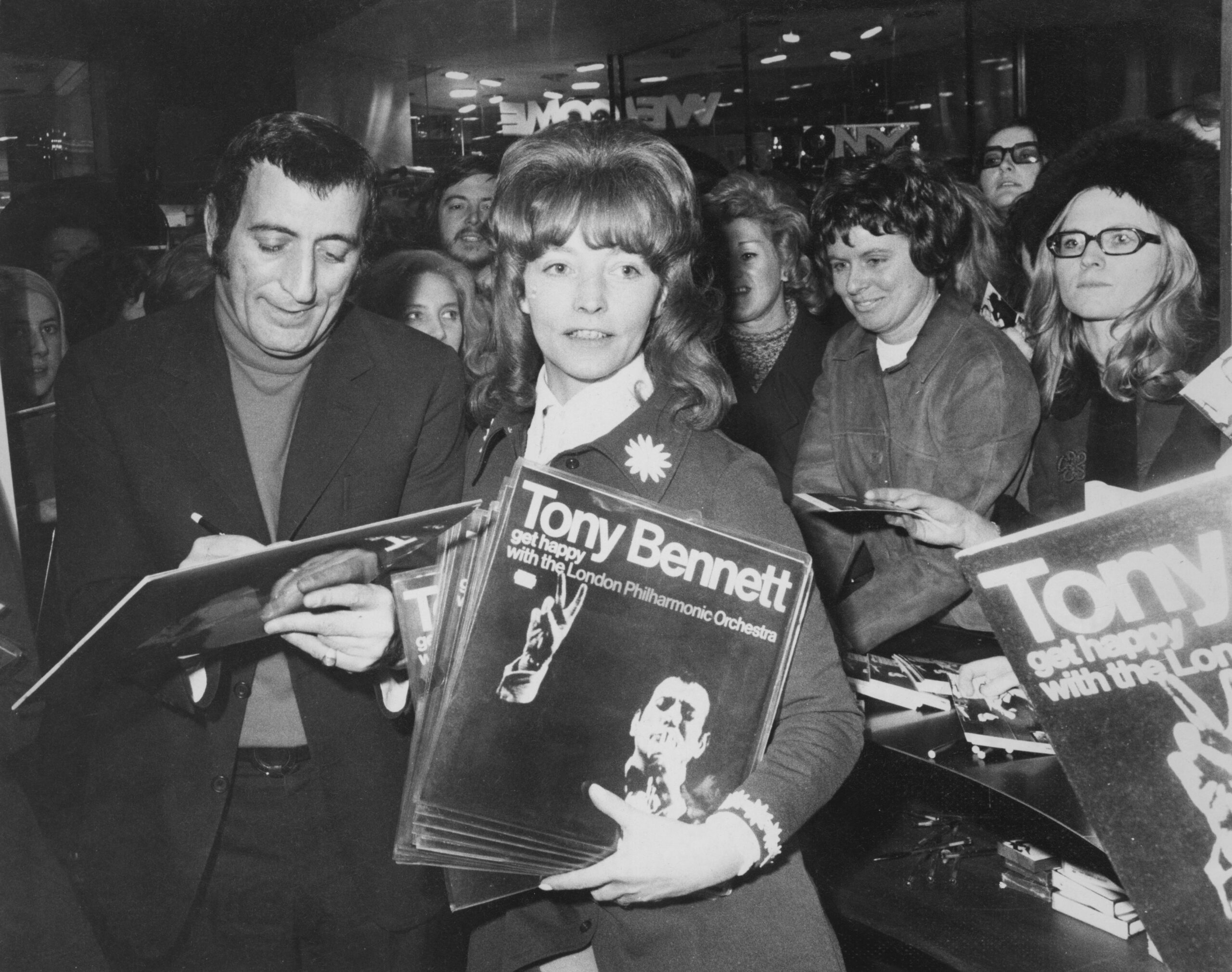

I did three albums a year for 23 years straight. It was good, though. It was a great musical adventure. To be able to sing with Bill Evans on the piano, to sing with the Philharmonic, to sing at Carnegie Hall, to sing with Count Basie and all these wonderful musicians — Zoot Sims, Buddy Rich, Woody Herman, and all of them. To rub shoulders with them and get to know them was a thrill. I met Art Tatum and Billie Holiday. I used to follow her into the recording studio. In those days we used to have to cut four songs in three-and-a-half hours. And those are her great standards today.

I just found out that when Mitch Miller found you, you were working with Bob Hope. How did that happen?

Pearl Bailey. She put me on her show to open up. I was the only white guy in a whole black show. I cracked Bob Hope up. “Look at this guy!” he said. “Let’s go uptown to the Paramount Theatre, I want to introduce you.”

And how did she find you?

I was singing in the club. It was the Greenwich Village Inn. She was coming in next week and she heard me sing and she said to the boss, “If you want me here next week you keep this boy on.”

Before that you were a singing waiter?

I was a singing waiter when I was 16. In Astoria, Long Island. That was fun. Two Irish waiters and myself. When I had to learn something like “My Gal Sal” or whatever that was requested that I didn’t know, we’d go in the kitchen and they’d teach it to me. I’d sing it and get an extra tip. Irving Berlin started out as a singing waiter.

Were you without a deal for a long time?

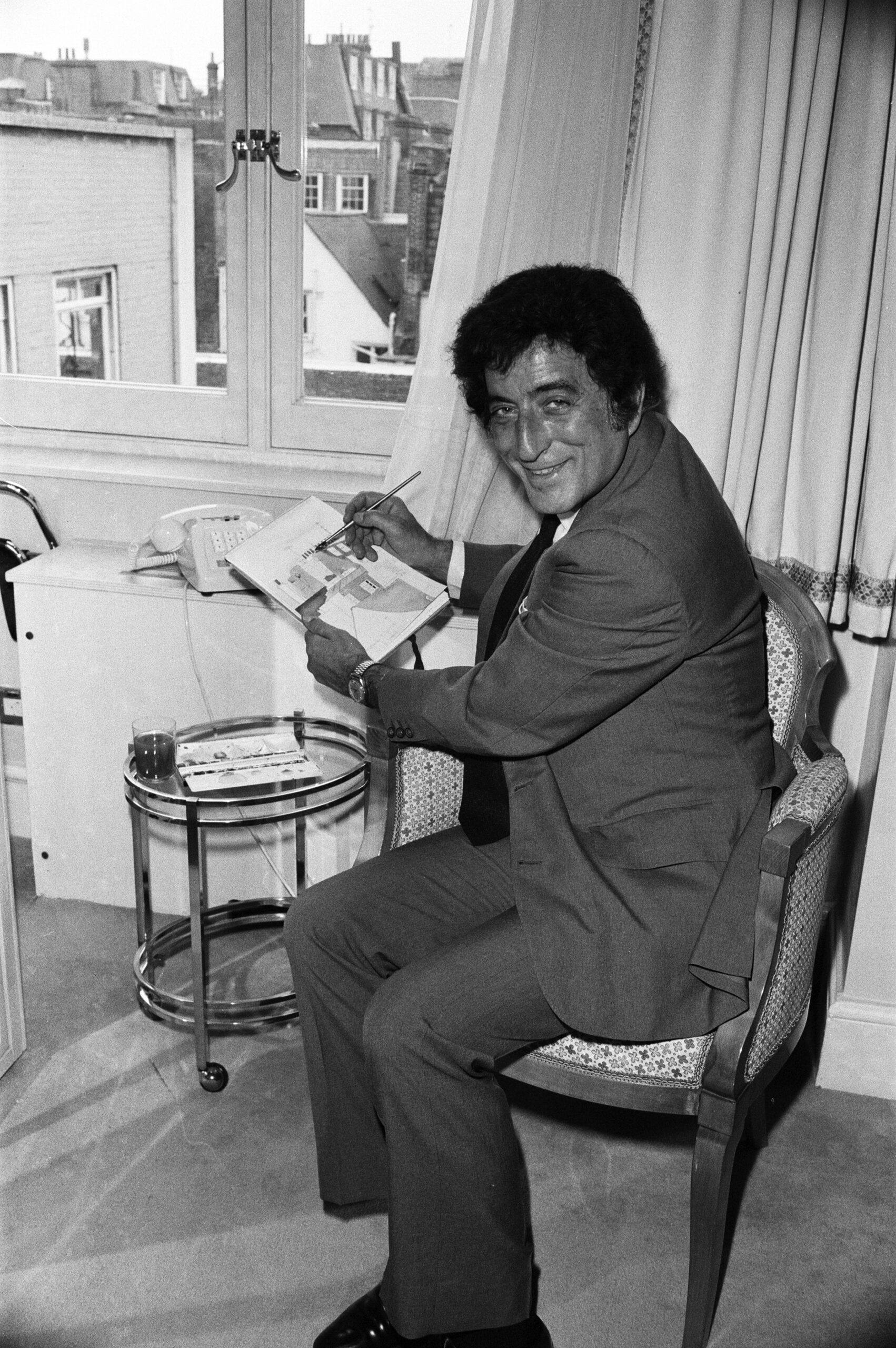

Yeah, but it wasn’t actually that I got booted out. It was my decision. I just painted. That’s what I really wanted to do. I’d never had enough time to paint.

The last album I made before my new deal was with Bill Evans. It was on my own label, Improv. I had a wonderful label. It had critical acclaim. It just didn’t have the distributorship. I made about five of my own records on that label, but I had many other artists on it. We had Charlie Byrd, we had Fatha Hines, Marian McPartland, Torri Zito . . . very good musicians and very good records.

There are smaller jazz labels that are doing well now. Like Flying Dutchman. Maybe you were just ahead of your time.

That’s what Mitch Miller used to tell me all the time. But he’d say it like it was a put-down. I’d say, “What’s wrong with that?” I’d say, “Let me be a spearhead. Let me be a scout.” The credits that I built up I’m proud of. I’m thrilled that my life turned out to be such a musical adventure. I went to Rio de Janeiro and one day a bass player named Don Payne said, “Come out to the beach. I want you to meet somebody.” I said, “Ahh . . .” He said, “Come on down. This is different.” I went down and I met Joao Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim, and Astrud Gilberto. They were on the beach just playing bossa nova. It was the first time I’d ever heard it. I brought it back to San Francisco from Rio and had the disc jockeys play it on the radio. I never saw anything catch on so fast in my life. But I actually brought the first Joao Gilberto records to America. In Rio they know it. But they don’t know it here. In Rio, if I’m coming down, they’ll preadvertise it as “The man who brought bossa nova to America.” They treat me like a king.

I also did a country record with a big string orchestra on it with Mitch Miller and Rosemary Clooney. Before that, country just had a certain instrumentation and it never broke out of that 300,000 record sales that Hank Williams used to do. We had the first crossover hits from country music. Rosemary and I sold two million records each. I did “Cold, Cold Heart.”

Did you think “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” would be a hit?

No. We did it out of necessity. We were going to San Francisco, to the Fairmont Hotel, for the first time. We were in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and there was Ralph, myself, and a bartender on an afternoon. We were writing the song down and the bartender said, “You record that song and I’ll buy it.” We thanked him, but we didn’t pay any attention. But then we recorded it and it just broke internationally. It just keeps selling. It’s still selling.

Do you ever get tired of people associating you with that song?

Not at all. You see, Maurice Chevalier, who is one of the great international performers, has been a role model for me. I travel all over the world now. And he was able to conquer every country. And he sang about Paris. And in the United States our Paris is San Francisco. It’s full of elegance, quality; it’s attained a very high degree of civilization. It’s handmade. It’s built beautifully. It’s funny, but in the 25 years I’ve been singing that song I’ve never met anybody who said that they were disappointed by a trip to San Francisco.

In your concert when you said that you and Sinatra were the last of the saloon singers, I thought, “Hey, what about Mel Torme?”

That’s what Sinatra says. He says that he and I are the only two. So you’ll have to ask him about that. If you have the courage.

Your voice still sounds great. Do you do anything to keep in shape?

I do 20 minutes of bel canto scales just to keep my voice in shape. I’m always thinking about music. Music and painting. I’m doing both all the time.

How long have you been painting?

My whole life.

Did you study?

I’ve studied a lot. I’m studying right now. I’m studying portrait painting right now. I’ve had nothing but good teachers. There’s a fellow named Rudolph de Harak who had a lot to do with building the Egyptian wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he’s like a brother to me. My mother had him come in with us when his mother died. He’s now the number-one graphic artist in America, and he’s always pointed me toward painting and put me into art schools. Then I had private tutors the rest of my life. But I like to go to schools, like the Academy of Art down in the Village. That’s a fantastic place. You have to learn form before you can be free, and they teach the old Michelangelo techniques of studying the bones and then the muscles and then the skin and then the shadings. You learn from the bottom up. And I like that kind of traditional teaching. There are no shortcuts and if you do it the right way it really gets good. I love the whole process.

Who are your favorite painters?

Well, among the masters I like Michelangelo. And then among modern painters I like David Hockney. I love David Hockney’s work. I consider him the greatest leader of the era. He has a way of improving the way we see things, a lot of new concepts that are legit. But there are so many. You fall in love with Matisse, with Cézanne, with Raphael. And the Chinese could see clearer than anybody.

So what do you think of Sinatra as a painter?

Well, he paints modern. I think he’s very good. The couple of things that I’ve seen of his are very nice. He knows what’s happening. His favorite painter is Frank Stella.

On your album Jazz, you play with some of the great musicians of our time. There are a lot of different sessions from different years. How did those sessions come about?

Well, like the Stan Getz sides with Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter and Art Blakey and Tony Williams . . . CBS used to have the 30th Street Studios. It was a big old church. Great studios. I heard Stan Getz was recording down there. It was a nice sunny Saturday afternoon. I said, “I’m gonna go down there and just sit in the booth and listen to this.” And sure enough it was great; they were cookin’. A wonderful group and a great sound engineer, Frank Laico. So all of a sudden Stan says on the speaker, “Come on, Tony, come out and sing with us.” I said, “You’re kidding. I just came here to hear you.” He said, “No, do a couple of sides.” And it was just that off-the-cuff, spontaneous kind of thing.

Basie and I just hit it off and we became buddies and I said, “Let’s do something on the road together.” And he said, “Well, come on.” That was that great fifties band that he had with Joe Williams. He was such a wonderful human being and a great humorist. I just loved being around him. He had a great aura about him. He would just look at an audience and they would react. He didn’t have to play a note.

She’s not on the album, but I was on the road with Lena Home for two-and-a-half years. She taught me how to be disciplined onstage. I had all these wonderful teachers. It’s almost like a performer has to fall in love with the whole business. And, funny enough, my peers have treated me so fantastically through the years. Just when I had my darkest periods of doubt, there would always be some entertainer who just lifted me right up by my bootstraps. Sinatra is the number-one guy. He said that I’m his favorite singer. Then Bing Crosby did it. Then Judy Garland did it. It’s even happened with my painting. LeRoy Neiman and David Hockney and Elaine de Kooning, these are the top people in the art world and they’re saying I know how to paint. I say, “Oh, you’re just saying that to make me feel good,” and they say, “Oh, no, you’re a painter, a strong painter. Just keep painting.” And it’s very encouraging. It lifts me up. It gets me inspired.

It seems that there was a lot more of a community of musicians when you were starting out.

There was an incredible scene. You had a land of geniuses. On 52nd Street, where I studied singing with Mimi Spear, a wonderful singing coach, she taught Peggy Lee and Helen O’Connell and Margaret Whiting, you’d look out her window at the awnings and you’d see all these clubs, and you had Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, George Shearing, Stan Getz, Oscar Peterson, Big Sid Catlett, you had Erroll Garner, you had Billie Holiday, all on one little street. You had all the great, great musicians who were famous in the bands. Ralph Bums is a great orchestrator, now of movies and Broadway, but originally he came out of Woody Herman and Count Basie’s band, along with Johnny Mandel and Neil Hefti and Bill Holman. These are the great orchestrators. And everybody found themselves migrating around Ralph Burns. You had Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Lee Konitz, all these magnificent players on the New York scene. It was just the best group of musicians I ever ran into ever, anywhere.

I loved it. It was a land of geniuses. We were all going somewhere. It was all happening. The audiences were fantastic. In those days they were the boss. Now, because of computers and media push and Madison Avenue philosophies, it’s all into demographics and accountants and people figuring things out. They don’t care whether the public gets it or not. They know the amount of promotion is what’s going to make it go. So it doesn’t even have to be good. It’s an obsolescence philosophy. But in those days they used to listen to the audience and whoever the audience applauded for the most were the ones that got booked. It was primitive, but it was really correct.

There are really a lot of promising young people coming up. The only problem really is that there’s no place, like George Bums says, “for them to get lousy before they get good.” It takes time to hone a good performance. That takes months. Years ago you had a circuit. You left New York and went all around the country and back and by the time you got back you were ready to play the Palace.

Also there used to be more of an accent on individualism. There was a difference between the way Erroll Garner played the piano and Art Tatum played the piano. But today it’s almost like a robot thing. Everybody’s doing the same thing. Things look pretty much alike. Everybody thinks they’re different, but they all look alike. Today, it’s almost like if you do something and it stands out they say, “Hey, you’re out of step here. You’re not wearing a yellow tie. What’s the matter with you?”

Do you remember the first time you heard bop?

Yeah, sure. Charlie Parker at Birdland. I went out in the street and regurgitated. Not in horror. But it moved me so much. I just went in and this guy put a horn in my face. He started playing and it had such intensity, it was so strong, I actually became ill from it, it was so great. It was the best thing I ever heard.

In the liner notes of Jazz, there’s a quote from your teacher Miriam Spires: “Don’t imitate singers, imitate musicians.”

Yes, that’s right. I imitated Art Tatum, the way he made a production out of a simple song. He’d take “Don’t Blame Me,” he’d get a good intro, he’d start with some incongruous tempo. he’d go out of tempo into tempo. It became a production. I liked Stan Getz and Zoot Sims, so I imitated that sound as far as tonal quality. By doing that you don’t sound like Dick Haymes or Frank Sinatra or Mick Jagger or anybody. You sound like yourself.

Who are your favorite female singers?

Ella Fitzgerald is way on top of the list. Then there’s Sarah Vaughan, Peggy Lee, Carmen McRae, Nancy Wilson, Rosemary Clooney. You know that’s something interesting. Girls . . . this is starting to happen to me with tennis, too, by the way . . . but they taught me more than any of the men.

I think there are more great women singers.

I think all women can sing. Even when they say they can’t. They really know how to sing. It’s just physical with them. What we have to learn through Zen, they know it already. There’s something laid back about them. They’re ahead of it, but they’re relaxed. They have a relaxed machine in them. Much more than a man, I think. But maybe it’s just the distortion of a greedy society that makes a man go out and become a slave or something. But who knows? I’m not a psychiatrist or a psychologist, but I was watching Chris Evert last night and she just has a way of hitting the ball that’s just right. It’s not pushing. It’s natural.

I’ve learned a lot from women singers through the years. Sylvia Sims. Mabel Mercer. Dinah Washington. There’s all these good singers and they all sing different.

Do you listen to music when you paint?

Oh yeah. I listen to Bach, I listen to Sinatra, I listen to Louis Armstrong, I listen to myself, I listen to Sinatra. Anything that just hits me nice.

I see that you sign your paintings “Benedetto.” That’s your real family name?

Yeah.

Do you know what it means?

It means “blessed one.”

As I was ready to leave, Tony wanted to play back some of my tape to hear if my recorder had picked up any of the solo cocktail-jazz flugelhorn being blown for spare change down on the sidewalk below Tony’s window.

Clear as a . . . flugelhorn echoing through the midtown rush-hour canyons. Tony was into it. And as I passed the guy on the street, steam oozing out of his horn, I couldn’t tell if he knew Tony was up there listening or not.

That’s show business.