In March of this year, a few weeks before thousands of electronic dance music fans (the most photogenic of which wore fuzzy boots and little else) swarmed Miami for Ultra Music Festival, Chicago house honcho Derrick Carter fired off some well-timed barbs on Twitter. Though he didn’t name names, it was pretty clear he was addressing some of the EDM-heavy headliners — Hardwell, Avicii, Alesso — that this latest generation of ravers had come to see. “If every track you play, has a gratuitous, unnecessary breakdown in it… you might be ‘derp house’,” he tweeted, before launching into a subtweet tirade hashtagged with his portmanteau of the genre deep house and the word “derp,” basically a synonym for boneheaded.

If it takes more than three DJs to play one set, you might be #DerpHouse

— Derrick Carter (@blucu) March 3, 2015

“If your V-neck is deeper than your music you might be #derphouse.” – Ben Siegert — Derrick Carter (@blucu) March 3, 2015

If that Korg M1 or Yamaha DX preset is your default bass sound…you might be #DerpHouse

— Derrick Carter (@blucu) March 3, 2015

For the uninitiated, the Korg M1 is a synthesizer, and here Carter refers to relatively cheap software that provides comparable plug-ins like that “default bass sound,” minor-chord keyboard phrases, and gated, percussive hand claps are commonly featured on songs by boilerplate artists on the label Spinnin’ Records. If you’ve ever listened to Top 40 radio, chances are you’ve heard some comparable program’s preset string melodies on a song like Armin Van Buuren’s “Another You” featuring Mr. Probz; that track’s unimaginative lyrics, wan melodies, and cut-and-paste builds and drops have become the signifiers of lowest-common-denominator EDM.

Deep house is starting to become equally formulaic: In a representative video, London DJs Disciples jokingly sing along to compatriot David Zowie’s straight-ahead ode to going buck, “House Every Weekend” while cuing up the chorus to “How Deep Is Your Love,” a song they essentially gifted to Calvin Harris, which is also his most legitimate attempt at a claim to house music’s legacy. The two songs overlap so perfectly they may as well be the same. And to many listeners these days, anything with romantically yearning vocals and a kicking beat constitutes deep house, a growing misconception that’s homogenized what began as a soulful safe space for a more marginalized audience.

Though the “deep house vs. deep house” debate seems at the surface like nothing more than a pissing match between historically significant makers of this kind of music and the snobs that critique it, the distinction is just as important as, say, the difference between “bro country” (which for a while represented country music on the Billboard charts and on the airwaves) and country music that’s about more than celebrating traditional displays of masculinity, like tailgating or hitting on chicks at bars. One of the very first tracks defined as “deep house,” Larry Heard’s smoothly mechanized 1988 jam “Can You Feel It?” as Mr. Fingers, originally gestated behind the decks of Chicago clubs like Warehouse (under house music’s minor deity Frankie Knuckles), a bastion of gay communities of color. Around the same time half a nation away in New York City, Larry Levan’s alcohol-free Paradise Garage welcomed all dancers — gay, straight, black, white — as long as they respected his sacrament of parting the undulating crowds to climb atop a ladder and clean the disco ball.

Now there isn’t nearly the same sense of communal participation in such body-moving music as many more people go to clubs not for the music, but to imbibe vodka shots and ask, “So who’s playing tonight?” as a way to strike up conversation with attractive strangers. “I’m so frustrated by guys sticking their fists into the DJ booth for hetero ‘bro’ fist bumps, which I refuse to bump back,” says prolific producer and intellectual Terre Thaemlitz, who goes by DJ Sprinkles. “At one of my DJ gigs in Brooklyn a couple years back, a trans-male friend of mine took it upon himself to run defense for women who were being encircled by aggressive drunk guys.”

Thaemlitz defines deep house — one of the forms of dance music she’s been producing for over 20 years now — as “primarily instrumental, mid-tempo (usually between 110 and 120 beats per minute), focusing on minor chords.” Her arguably best-known release, 2009’s Midtown 120 Blues, fulfills this criteria with sublimely melancholic pianos and meditations on why Madonna’s “Vogue” has no claim on dance music rooted in African-American and Latino identities. Just four years later, in 2013, deep house went bigger, louder, and more mainstream with four-on-the-floor stompers like Duke Dumont’s euphoric “(Need U) 100%” and Disclosure’s inescapable “Latch”; and two years after that, both of those formerly U.K. garage revival producers have transitioned into full-blown pop. Disclosure have slowed down the tempo and amped up the guest-star wattage on this year’s Caracal, and Dumont’s “Ocean Drive” sounds more like the Drive soundtrack than anything Levan might have spun 25 years ago. Because of such rapid genre-shuffling, there still seems to be some confusion about how to classify Disclosure’s Lawrence Brothers — just look at the “What genre is Disclosure?” thread on the EDM subreddit — even though the duo themselves adamantly maintain they are not deep house.

Self-imposed genre watchdog Carter (who did not respond to interview requests for this article) has been outspoken about dance music’s increasingly white audience, thanks largely to those artists’ perennial positions on the Top 40 airwaves, a transition similar to what’s been happening in hip-hop. He elucidated his concerns in a Facebook post last year after rapper and rabble-rouser Azealia Banks criticized Iggy Azalea for appropriating black culture: “Something that started as a gay black/Latino club music and is now sold, shuffled, and packaged as having very little to do with either,” he wrote. “RA top 100, DJ top 100, hell ANY top 100…show me the gay brown faces — S**t! Show me EITHER the gay or brown faces — and then discuss ‘cultural smudging’.”

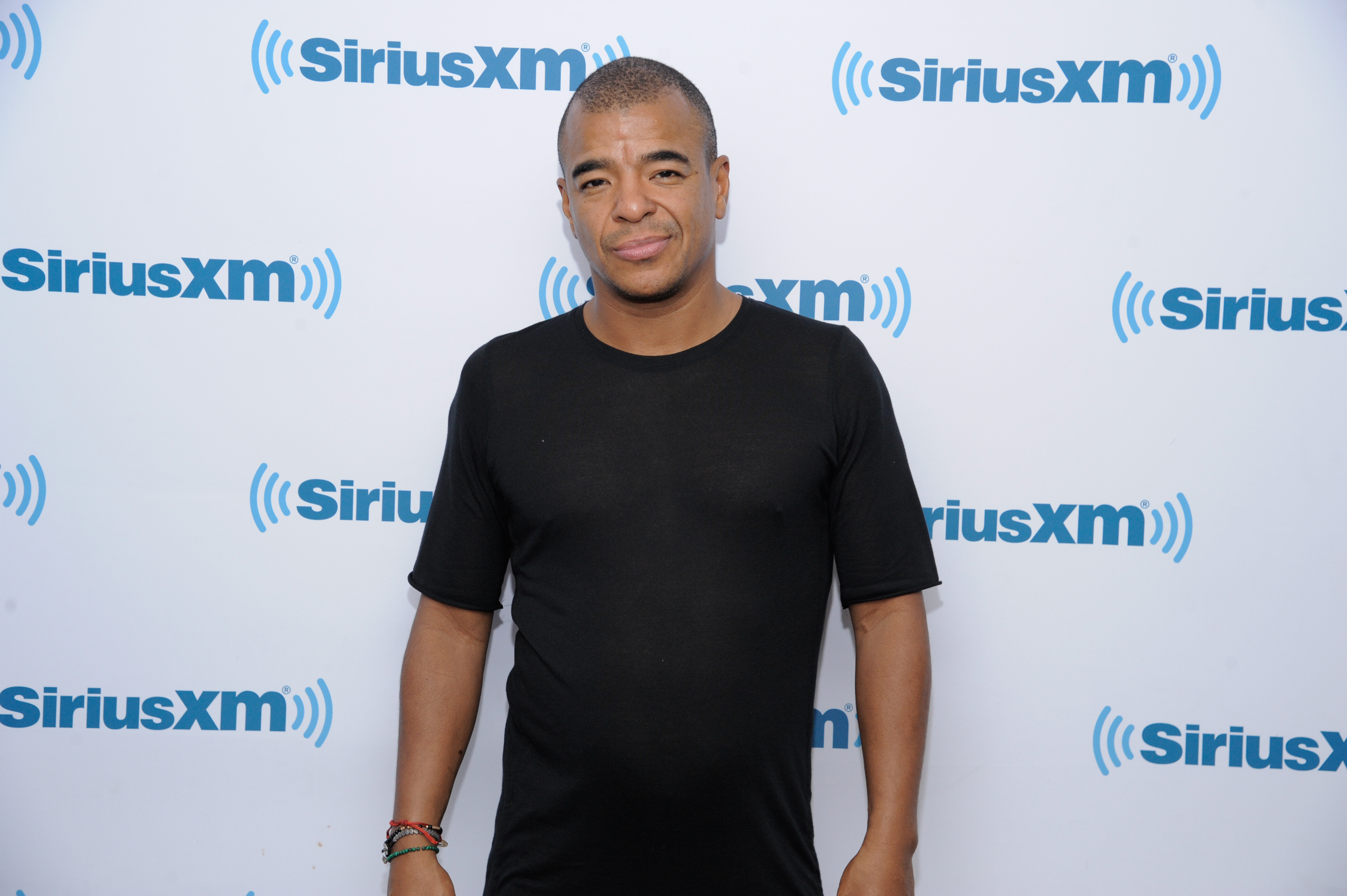

This whitewashing can be seen in Beatport’s Deep House Top 100 Releases, yet another tier of mainstreamed deep-house music that iconic Windy City producer (and Ibiza staple) Erick Morillo tells SPIN is sort of an industry bellwether in America. It’s dominated by Euro-centric artists like Tiësto protegé Oliver Heldens, or the mysteriously smooth and masked Claptone, who recently topped the rankings. Clocking in at 120 BPM, the enigmatic DJ’s easy, breezy, Balearic-beautiful single “The Only Thing” lands somewhere between lounge jazz and electro-pop. Pleasant enough, it still pales in comparison to the brawn and soul of deep-house OGs like Little Louis Vega’s 1993 belter, “Deep Inside,” or the bracing piano bars of Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body” from 1986. Those were harder, closer to the chest, meant for all-nighters in the dank and dark warehouses of Midwest cities, not plushly outfitted midtown Manhattan clubs advertising bottle service and ladies’ nights, or Vegas venues where Calvin Harris will publicly shame audience members who don’t like his build-and-drop shtick.

Michaelangelo Matos, a dance and electronic music journalist, classifies the Claptones of the world as “shallow house.” “It doesn’t always have the gushing melodies and sonic profile, but the builds are really similar, the way that it surges,” he says. “It’s like the difference between R&B and deep soul. Deep soul implies church. If you were to say, ‘Rihanna is deep soul,’ people would look at you like you were nuts.”

New York-via-Detroit producer MK — a frequent, seasoned interviewee about this exact subject — started making house tracks in the ’90s “when it wasn’t as popular as it is now,” he tells SPIN. “Now, it’s different. House music is bigger than some rap music. That didn’t happen back then.” After remixing “Push the Feeling On” by Scottish one-hit wonders Nightcrawlers and subsequently becoming disillusioned with requests to make more tracks with its exact sonic profile, MK retreated from behind the decks to produce and remix superstars — including Michael Jackson, Pet Shop Boys, Moby, and New Order — as Marc Kinchen. Ten years later, he came back with reworks of the 2011 groove magnet “Look Right Through” by Jersey-bred remixer Storm Queen and Berlin newcomer Wankelmut’s unstoppable “My Head Is a Jungle” from 2013. The latter especially, with its lifted keys and relentless drive, feels like a more organic re-assemblage of the floor-fillers that preceded and inspired the first wave of MK’s career. Now, unlike Carter, MK is more forgiving of the fist-pumping dude-bros in tank tops who flock to the increasingly crowded Brooklyn sweatbox Verboten, regardless of whether it’s Disclosure’s peers in Gorgon City or legendary vinyl maestro Danny Tenaglia on deck. To him, the rising tide of interest in deep house lifts all DJs and producers, even if it dilutes the most popular strains of that music.

There doesn’t seem to be a solution yet for the increased masculinity of the audience and ensuing loss of diversity in the music the crowds pay to see, but there are those trying to reclaim — or at least respectfully re-imagine — deep house’s origins. In the United States, Queens newcomer Galcher Lustwerk fractures signature tropes with prismatic synthpads and deadpan delivery, while boutique Los Angeles label 100% Silk noses for only the sultriest seven-inches. Across one ocean there’s Hunee, in Amsterdam, who practically time-travels 20-plus years (at the minimum) for his vocal- and piano-driven DJ sets; and in the other direction there’s Tokyo-based producer Gonno, whose 2015 LP, Remember the Life Is Beautiful, could be read as another reminder that deep house doesn’t have to be quite as banal as what’s blaring from the radio, topping the Beatport charts, or shuddering festival main stages. Even Output, a mid-sized dance club that generally caters to upper-middle class members of the finance industry who’ve recently relocated to Williamsburg, hosted DJ Sprinkles and Brooklyn-based house-music maven Ital in its velvet-walled Panther Room.

As long as you’re not looking at the headliner stages or most-trafficked clubs, deep house is still alive and dancing; you won’t find the kind of margin-pushing house music Thaemlitz remembers and celebrates at EDM festivals. As 4/4 beats and their bejeweled melodies rise to the top of the Billboard charts and take over larger platforms, more adventurous house music will continue to retreat further underground. The ensuing whiter and wealthier audience probably wouldn’t have recognized the sample of Lil Louis’ 1989 “French Kiss,” a vaguely pornographic classic that perennial Beatport Deep House chart-topper DJ Solomun mixed into one of his sets. Still, the hope glimmers that deep house’s mainstreaming will be remembered as just a trend of this year that was quickly replaced by the increasingly mass consumption and dilution of another dance music genre — one need only look at this year’s long-running Detroit-based techno festival, Movement, which featured Snoop Dogg at the top of its bill. Rhythm is a dancer, after all.

“When Deadmau5 does a record and does the drops?” Morillo asks rhetorically. “It’s all house. When they start making all these categories I think it’s kind of silly but fine, divide it all up. It’s all house at the end of the day.”