To be a one-man band, you once needed a harp rack at your mouth, a bass drum on your back, cymbals between your knees, tambourines on your sleeves, and the willingness to appear a little mad. Now, if you’re Colin Stetson, all you need is a big old sax that’s mic’d up like a Stasi break room, a raft of extended techniques to command, the endurance to breathe life into your hypnotic mosaics for long periods, and the willingness to appear a little mad. (Actually, all you need is a computer, but we’ll come back to that.)

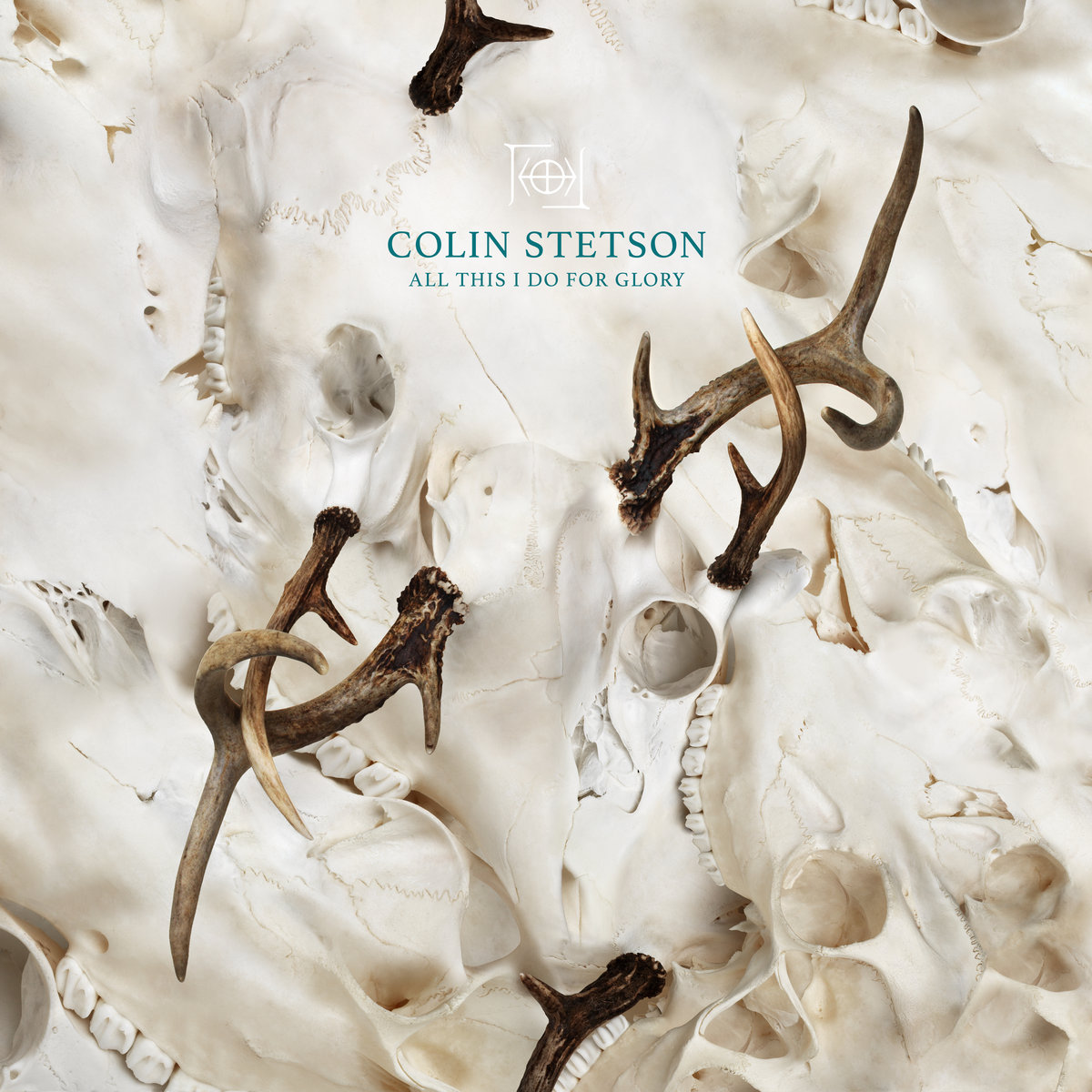

All This I Do for Glory is Stetson’s latest solo album, which means it’s neither too pop nor too classical—the kind of thing he concocts between wailing for the masses with Arcade Fire and reinterpreting Polish modernist symphonies. Consistent with his acclaimed “New History Warfare” series, it captures a human arpeggiator reconstituting post-minimalism, jazz, and metal in growling, moaning pieces with far more syncopated parts—percussion, bass, melody, harmony—than one guy recording without overdubs should rightfully account for.

Stetson is a miser of sound, unwilling to forfeit any squeak or click. Using techniques like overblowing, circular breathing, venting, singing through the reed, and clacking valves, he striates visceral motifs with subtle timbres and microtones. The new album displays his usual chiaroscuro, alternating dark-hued, bassy coils with crystalline ostinatos, but retro IDM influences give it a new slant. The dancing counterpoint and whooshing dynamics of “Like Wolves on the Fold” are as redolent of Aphex Twin as Philip Glass, and there are also more surprising results: the title track’s grungy, granular riffs and disembodied voices sharply recall the sludgy dub of early Liars.

Two tracks begin by capturing Stetson’s first intake of breath, and it’s breathtaking to hear it circulate at length through the strange new instrument his body and horn fuse into. The grueling physicality of the act matches the tenacity and drive of the compositional voice. When hyperreal music can easily be made with digital tools, Stetson’s way is perversely arduous and thrillingly inefficient. Why does he do it? The title says it all.