Release Date: March 12, 2013

Label: Nonesuch

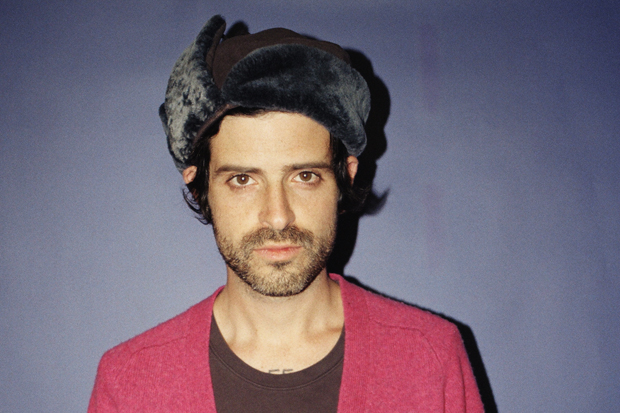

Somewhere in Topanga Canyon (or perhaps on Manhattan’s Lower East Side), Devendra Banhart sits, musing that he might have been crowned King of Chillwave just as easily as he was dubbed Lord of Freak Folk. The Niño Rojo. The Man Who Would Be (Ariel) Pink. And for wont of huaraches, the kingdom was lost. Yet on Mala, his eighth studio album and first in four years, the man seems content amid broken relationships — freed of all expectations, and engaged, literally (the record’s title is inscribed on a ring from his fiancée, photographer Ana Kraš).

At the turn of the 21st century, not-yet-21 Banhart was a five-tool player on the New York farm-glam scene: preternatural troubadour, surreal lyricist, nimble fingerpicker, and enigmatic outsider visual artist, all of it topped off with photogenic Jesus locks and stars in his beard. Riding a white swan, he crooned songs onto Michael Gira’s home answering machine, penned drawings for SoHo gallery shows, and effortlessly rendered home recordings at a Rumpelstiltskin-ian clip, as evinced on his breathless debut Oh Me Oh My…. The golden child’s next two albums, 2004’s Rejoicing in the Hands and Niño Rojo, were released within six months of each other.

Meanwhile, he became the Father Yod figure for “freak folk,” a calico collective which included harp-plucking pixie Joanna Newsom, soft-rockers Vetiver, eccentric androgynous uncle Antony, and in-drag drags CocoRosie. Almost all of whom eventually appeared at Carnegie Hall. Crazy-eyed at center stage, Banhart started to look a tad Manson-esque. (The title of a 2004 tour doc of those freak-folkers? The Family Jams.)

But just as swiftly as he jumped to the West Coast (and to British label XL) for 2005’s Cripple Crow, he also jumped the shark. Banhart showed at Art Basel, showed his acting chops in Nick and Nora’s Infinite Playlist, was showcased as a bearded lady in a T Magazine spread, and showed up in a Page Six item alongside Natalie Portman. But Crow sounded like he winged it. Therein followed a trustafarian reggae move and albums that sounded like a bored perusal of Other Music’s international section. Meanwhile, a Newer, Weirder America was being rendered on the same coast by Angeleno Ariel Pink, fuzzy with tape hiss and equally prolific, cheeky, creepy, androgynous, and glam-gunked as Banhart once had been. Maybe he should have been trading tapes with R. Stevie Moore rather than recording with Vashti Bunyan and Linda Perhacs.

Now comes Mala, which — damn it — is a more gratifying listen than the oft-grating Banhart had any right to deliver to non-believers in 2013. Tidy and concise, clocking in at 43 minutes, it favors the diminutive gesture to the cloying, hammy affectation that derailed so much of his prior discography. Rather than bray, he soothes. Rather than try on a bunch of eclectic genres, he maintains a slinky, low-key mood throughout. Rather than come on too strong, he subtly woos.

Again, Banhart works with longtime drummer and producer Noah Georgeson, but finally the folk timbres have been embellished with some subtle electronics via synth washes and dusty drum machines. See the koan/command “Get on the dance floor” on opener “Golden Girls,” which somehow combines cello, dulcimer, “Dirty Boots” moodiness, and a subliminal bass throb in just under 96 seconds. There’s a percolating analog gurgle and thrum on “Never Seen Such Good Things.” And “Your Fine Petting Duck” begins as a ’50s doo-wop duet with Kraš before slyly veering into a droll, Teutonic take on Human League-style techno-pop.

Lyrically, he still shades toward the surreal; thankfully, the synths and drum machines make palatably whimsical a two-part reimagining of 12th-century Christian mystic Hildegard Von Bingen as an MTV VJ. But primarily, love and its loss resonates through Mala. On “Daniel,” Banhart renders a song of unrequited love that transpires while waiting in line to see Suede play at the Castro. Elsewhere, a relationship is compared to a bombed-out building, to a drunk pissing in an alley, and then to that storied 20th-century mystic, Paradise Garage DJ Larry Levan.

Rather than wallow in pathos or brood for an entire album over a failed relationship, Banhart delivers deadbeat zings like, “If we ever make sweet love again / I’m sure that it will be quite disgusting” and “If he doesn’t try his best / Please remember that I never tried at all.” The album’s lone misstep is a crude ode to the ol’ “Hatchet Wound,” a blatant riff on Ariel Pink. The best moment comes when Banhart sings about love as tenderly as he ever has on the penultimate “Won’t You Come Home”: As guitars gently ripple about, he coos, “Can’t see the shape of the song that we’re singing.” Only it sounds like he’s finally found the shape that best suits him.