Release Date: January 14, 2014

Label: Columbia

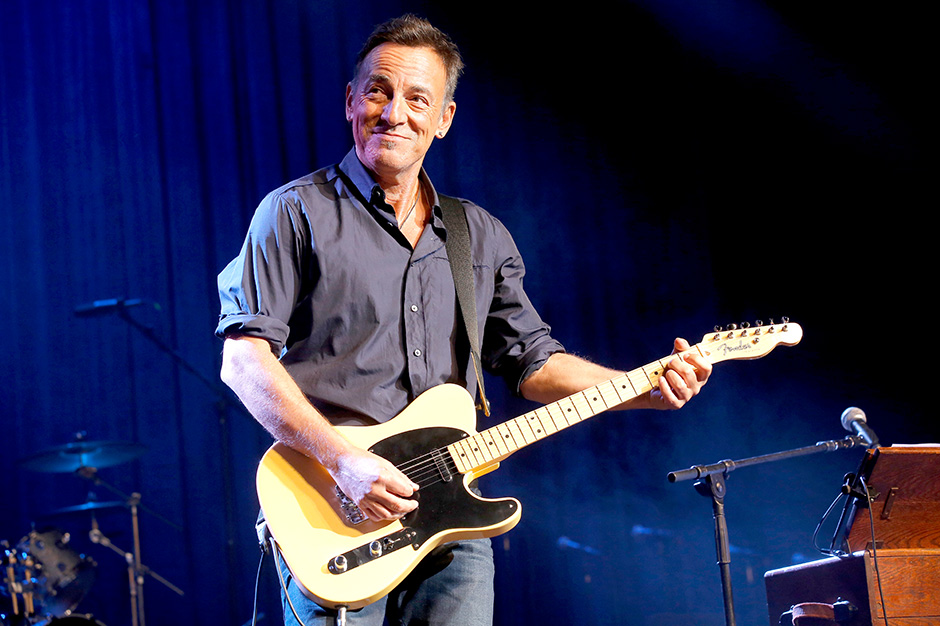

The magic trick that still powers Bruce Springsteen’s epochal career is his ability to rescue clichés, trick them out with an impossible earnestness, and make them resonate as fresh, thrilling sentiments. He’s now four decades into a grand thematic vamp about the life and death of blue-collar America, forever bringing our shame, sadness, and unsaid longing into high relief via a visceral rock’n’roll exegesis. And when he connects, it’s breathtaking: Jersey-born and Jesus-haunted, the dude affirms all those tired old feel-good rock mythologies and revitalizes the very possibility of music as a way to make sense of our pain. Conjuring once more our long-gone youth, and uncorking the vitality that capitalism and cynicism long sucked from our bones, he leaves us splayed out on the gleaming Camaro hood of our own childlike minds, guzzling beer with the Magic Rat.

So when he screws up (he hit Peak Corn with 1987’s Tunnel of Love, with brief echoing flubs on the 10 or so albums since), it’s still respectable, because he’s the Boss, his commitment as solemn as a vow. You always know he means it. But now, on odds-and-ends collection High Hopes, he joins forces with ex-Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello (who more recently has fashioned himself as the Woody Guthrie of the Occupy movement), and the equation is thrown off, casting the Boss into an ocean of cheese. The decade-spanning covers, outtakes, and remakes here — all these disparate moods and eras — make for an unwieldy mish-mash of an album with its seams apparent.

Springsteen has widely cited Morello, who filled in for Steven Van Zandt on an E Street Band tour of Australia, as this record’s muse — a presence who re-ignited and upgraded these rather disconnectedsongs. That enchantment is clear: The RATM engine gets seemingly free reign to apply his signature sound to nine of these 12 tracks. But rather than cloaking himself in Springsteen’s familiar arena-rock grandeur, the guitarist simply exhumes his own early-90’s-defining sound — post-Slash shredding, asynthetic metal-core crunch — and simply slaps it on top, as though he just stepped out of a Tardis from 1993. Morello’s vast influence and distinctive style is a cross to bear, certainly, and it gets the better of him here, resulting in solos so hammy yet pedestrian that they bring to mind a Guitar Center sales floor. The other issue is that such a flashy, relatively “now” sound applied to a record with a lot of vintage soul flourishes (horns, gospel-y backing vox, etc.) evokes a bungled attempt by a late-career artist to reassert his or her cultural primacy, like rapped verses in a Top 40 country song.

This is the small tragedy of the uneven High Hopes: that it doesn’t play like a Springsteen album. It’s well within the Boss’ right to try and freshen up old material, especially 18 albums in, but this one lacks a through-line beyond the distracting (and occasionally straight-up embarrassing) Morello. “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” a 1995 song about the homeless and hungry that marked the Boss’ return to more personal-political narratives (and already got a blaring RATM cover), did not need to be remade yet again with DJ-scratch-simulating guitar replacing the original harmonica parts. Yes, that really happens! Or see the pseudo-“Amen” break on Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream,” a treacly revision with a sweeping string arrangement that offers its own wan ’90s throwback. And the sinewy white fonk of “Harry’s Place” sounds like the sort of smuggler’s-blues perpetrated by lesser artists (all peace due to the Big Man, Clarence Clemons, whose posthumous sax provides welcome relief). There are some astounding low spots on this record.

Also Read

SAME AS THE OLD BOSS

Fortunately, even Morello’s three solos can’t tamp the intensity of “American Skin (41 Shots),” a 2001 song written for NYPD shooting victim Amadou Diallo, now given a terrible new potency in light of the far more recent murders of Trayvon Martin and Renisha McBride (“You can get killed just for living in / Your American skin”). The modest enormity of “Down in the Hole” (with its fiddles, children’s chorus, and organ) or the boyish energy of “Frankie Fell in Love” bring all the muchness down to calmer, more familiar ground. (Speaking of organ, fellow dearly departed E Streeter Danny Federici shows up on a few tracks, too.) And buried near the end is the quiet late-era classic “Hunter of Invisible Game,” a countrypolitan psalm wherein the Boss, slurring like Dylan about “empires of dust,” dishes up tenderness and apocalyptic retrospection amid the languid, Bacharachian strings. It’s an odd confluence, but unlike much of the rest of High Hopes, it works.