On the night before Donald Trump would be sworn in as the 45th president of the United States, the Washington D.C. rock band Priests was unwinding at the stately Silver Spring house owned by musicians Kevin Erickson and Hugh McElroy, who’d championed the band at the start of their careers. The next day, Priests were set to stage No Thanks, a charity show at the D.C. rock club Black Cat--it would feature artists such as Waxahatchee and Ted Leo, and raise funds for Casa Ruby and One DC, local organizations that aid the LGBT community and fight gentrification.

Though Priests hadn’t been announced on the bill until a week before the show, the benefit was constructed with their involvement in mind; the band had withheld the announcement to make sure other things fell in place first. (Another benefit, proposed shortly after the election, fell apart over trouble with the venue.) For No Thanks, every artist on the bill had agreed to play for free; the show sold out the day before, massaging fears they would potentially lose money if not enough people showed up.

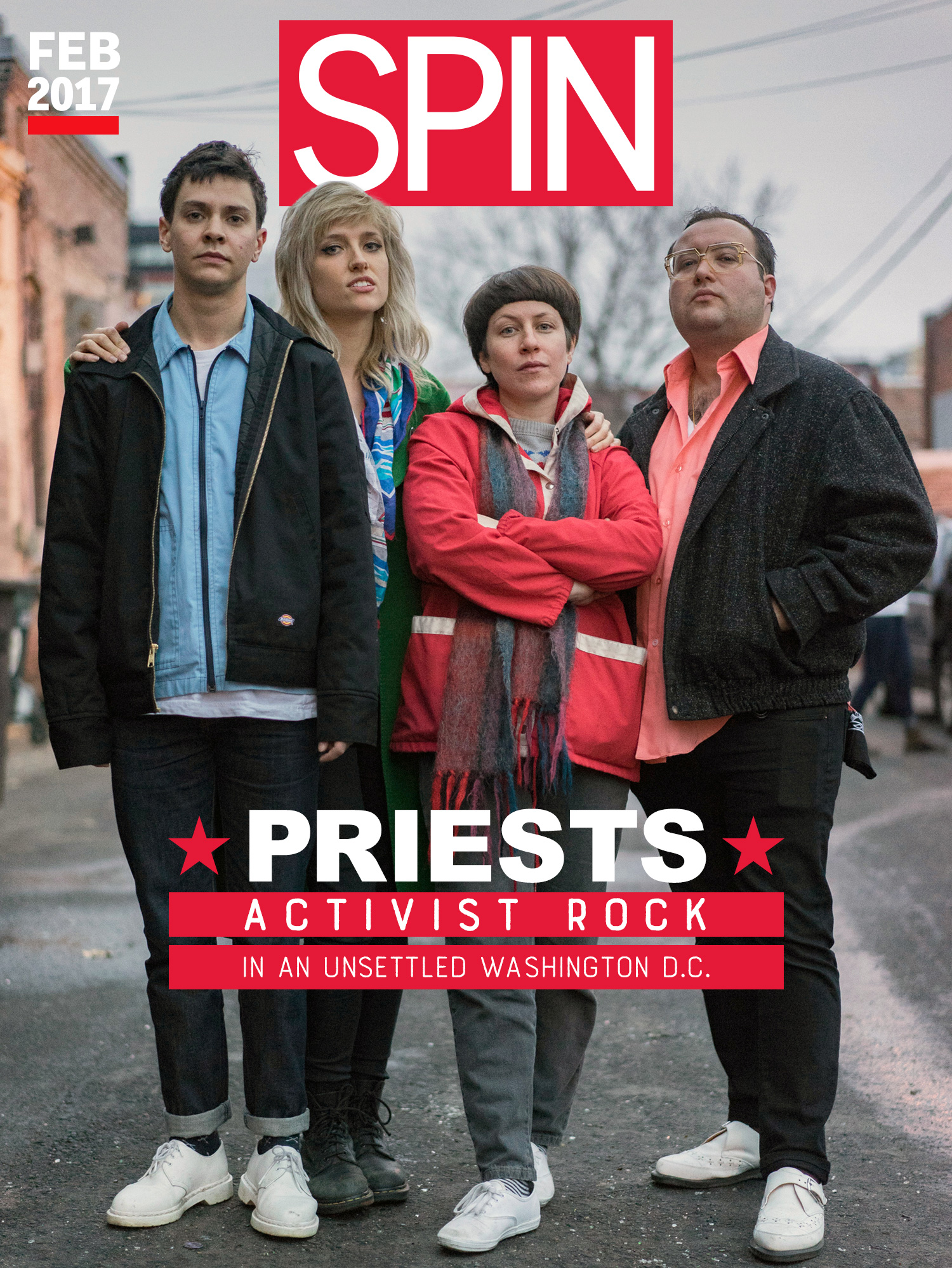

Katie Alice Greer, Priests’ singer and primary lyricist, stoked a pile of logs in the fireplace as drummer Daniele Daniele and guitarist GL Jaguar relaxed on a living room couch. (Bassist Taylor Mulitz was still out, working his restaurant shift.) In December, Greer had started living at Erickson and McElroy’s house following a tumultuous period in which she moved five times in three years, only once by choice. That uneven patch coincided with a down mood for Priests, who were gearing up to finally, after more than five years together, release their debut album--the due date for Nothing Feels Natural was January 27, one week into the Trump presidency. “We've been a very slow and steady band, but it's because our art is very important to us and we want it to be what we want it to be,” Greer said. “We're not just throwing paint at the wall to wait and see what it looks like when it dries.”

During inauguration weekend, the Silver Spring house was set to host Greer’s parents, the musician Sadie Dupuis (who was playing at the benefit), a pair of music writers (one of whom wrote the 36-page zine that accompanied their release), and many more house guests taking advantage of the space for the forthcoming Women's March. Priests was set to begin a national tour the following week, but that concern felt too far away to worry about; the fact of Trump’s presidency was settling in, and the band was resolved to hold down their hometown. “Hundreds of thousands of people come to our city and trash it, whether they're in favor of Donald Trump or against him,” Greer said. “And then we’re left to pick up the mess.”

[featuredStoryParallax id="225117" thumb="https://static.spin.com/files/2017/02/DSC03680-1486053135-300x200.jpg"]

In 2011, Daniele moved from Brooklyn to D.C. to get a Master’s in English at Georgetown. A week after coming to town, she met Greer at a Foul Swoops show. “I was really determined to start a band,” Greer says. “I was pretty immediately like, ‘Cool, you play drums? You want to start a band with me? Great, we're gonna do it.’” (Daniele had, in fact, just started to learn drums after purchasing a kit.) Soon after, Greer connected with Jaguar at a Black Cat show—(the two had been Facebook friends while attending American University, but had never met)—where they took each other up on an offer to jam.

The three started to play as Priests, releasing a debut tape and single in short succession. They became a four-piece in 2012 when Mulitz started playing with the band as Greer was on tour with her other group, Ian Svenonius’ Chain and the Gang. A slow trickle of material came over the next few years, as the band won notice for their charged songwriting and lightning rod live performances, influenced by D.C. bands like Fugazi and galvanized by Greer’s whiplash presence and Jaguar’s physical playing style. (Jaguar and Mulitz grew up in D.C., while Greer is from Michigan and Daniele was raised in Texas and Colorado.)

[caption id="attachment_id_225126"]  Photo by Pete Voelker[/caption]

Photo by Pete Voelker[/caption]

Nothing Feels Natural did not come easily. It was recorded first in Olympia, Washington, though the band found that initial takes were disappointing. Daniele, who hoped to have the record out before her 30th birthday (which passed in March 2016), was resolved to get it over with and move on to the next project, but Jaguar and Mulitz hatched a plan: They suggested re-recording two of the more unusable songs in D.C. with McElroy and Erickson, whose Swim-Two-Birds studio is in the basement of their home.

When those new takes turned out well, Jaguar and Mulitz insisted on re-recording the entire album. By her own account, Daniele, who keeps rigorous watch over the band’s schedule and finances—her Facebook lists her job as “Accountant at Priests”—lost her damn mind. Why not wait until she turned fifty? Why didn’t they take twenty years to finish the album? “I was just so, so angry,” she said. Erickson, who says he thought their new songs could “change people’s minds,” was afraid the band would dissolve before releasing the record; Daniele told Greer she would quit the band if Mulitz and Jaguar got their way. They did, Daniele never quit, and the record was completed over a series of weekends beginning in March and ending in the summer.

“We weren't getting along,” Katie said. “None of us had any money; all of us were on the outs of our jobs for taking so much time off. There were just a lot of pressures coming down on us, which I think made it hard for us to get along. In the back of my mind, I thought, ‘Is this the equivalent of when someone is super depressed and just makes all these subconsciously shitty life decisions to sabotage their life because they're too depressed to do good things? Are we just trying to kill the band without actually break up the band?’”

Every member in Priests has veto power over the band’s decisions, and they aren’t shy about exposing the fault lines beneath their group struggles. When I ask how Daniele ended up penning the lyrics to “No Big Bang,” a stunning spoken word piece about feeling paralyzed by the future’s possibilities, and the only song on Nothing Feels Natural not written by Greer, Daniele says it’s because Greer was moving too slowly. “One of the things we both struggle with is that we’re competitive,” she said, “and there was a part of me in the back of my mind going, ‘This will put a burner under Katie’s butt!’”

“So that song is about Katie,” Mulitz said, smiling. “No, I’m just kidding.”

“I was just so sad,” Greer said of her songwriting lapse. “It wasn’t that I was being lazy or something. I was working in a restaurant where sometimes I had to be in at 6 a.m., and then I’d have to get to practice. I would have to go into the bathroom where I worked and try to quietly cry and then come back and try to not look like I had been crying. I was in such a bad place.”

https://www.youtube.com/embed/VbWfKVBpvZY

A well-circulated story in the band’s mythology is a 2013 show booked by Pitchfork at the now-defunct Brooklyn venue 285 Kent. The concert was sponsored by Doc Martens; Priests, driven by insouciance and their conflicted feelings about the brand association, lobbed Chipotle burritos into the crowd and thanked Chipotle for sponsoring them. But anti-corporate credibility doesn’t pay the bills, and for the band to continue writing music without working themselves to the bone, they had to compromise.

“We've realized that if we want to make the art that we want to make, which is the first priority, then the way we're doing it right now is not sustainable,” Daniele said. With increased exposure from the new record, offers to play bigger shows and festivals would be likely to roll in—and Priests, who hired a booking agent and a publicist for the first time to manage the surge in interest, said they’d probably accept. “If I have to one-time partner with a shitty capitalist with a lot of money, that's OK. I'd rather do that than partner with a shitty capitalist who's running a record label, who's then going to have control of my music going forward.”

Carson Cox, the lead singer of Merchandise, was also staying at the house, and sat in during our interview. During a discussion of their hectic work schedules, he interrupted to point out their work ethic. “You guys are the only band I know that practices at eight o'clock in the morning because they literally can't do it at any other time,” he said. “I don't know anybody else who's like that. It's inspiring; it's important that somebody cares so much about what they're doing that they're willing to treat it like the military.”

“But it doesn't feel like that,” Greer said. “That's the point: We’re all here, and we really want to do this. It's like a relationship or building anything else that you really believe in. You're gonna go through rough patches sometimes or less-than-ideal circumstances, but if it's who you want to be with and what you want to do, it doesn't feel like torture.”

Daniele jumped in: “Plus, we realized that we want to make art that is really beautiful and takes a lot of time and as it turns out, costs a lot of money, mostly because we want to control it ourselves.”

Before she could finish the thought, Greer cut her off. “I don't want to make art that takes a lot of time,” she said. “I'm hoping this next record, we write in two weeks.”

[featuredStoryParallax id="225119" thumb="https://static.spin.com/files/2017/02/DSC03533-1486053266-300x200.jpg"]

Around the time Trump was elected, an oft-repeated canard declared his rise would make punk great again. Barack Obama’s presidency was characterized by all that hopey changey stuff, hardly a target for righteous rebellion. After a long hiatus, angsty and angry kids in garages across the country would have a machine to rage against.

This fantasy ignores all the potent music released over the last eight years that did criticize the 44th president for his part in enabling a system that continues to kill people abroad and at home, for however little it seemed to diminish his reputation as the coolest president since Bill Clinton answered “boxers or briefs?” and whipped out his sax. Lupe Fiasco vowed not to vote for Obama because of his inability to ease Israel/Palestine tensions, and performed it at an Obama inauguration party in 2013; ANOHNI wrote a painful lament for the drone strikes and the imprisonment of Chelsea Manning (whose 35-year prison sentence Obama commuted during his last week in office); Killer Mike compared him unfavorably to Ronald Reagan.

But to me, the most powerful declaration came from “And Breeding,” a song that closed out Priests’ 2014 EP Bodies and Control and Money and Power. “Barack Obama killed something in me,” Greer snarled, following a ferocious litany against the shallow patterns of modern life, “and I’m going to get him for it.” Coming from a generation raised on “Yes we can,” it was a brave declaration. Here was hope and change, deferred indefinitely—the song a naked admission of idealism curdled by the steady thrum of exposes about mass surveillance and drone strikes.

Priests are often described as a political band and as a punk band, or if you want to mark off the music critic bingo card, as a political punk band. As a genre descriptor, it’s basically worthless: All music is political, except maybe Ed Sheeran. The music, too, is broader than the aggressive power chords and lyrical snottiness inferred by calling something punk. Nothing Feels Natural features saxophones and oboes and piano, surf rock guitar leads and disco drum beats—its reference point was Portishead’s Third, and the band’s dreamy musical vision extends past some pissed-off kids bashing it out in a garage.

Nevertheless, the co-opting of punk as some idealized standard of rebellion puts the band on edge, and eager to dismiss imagined comparisons. When I brought up the idea that some people think “punk” might be better under Trump, Jaguar leapt in: “That’s so fucking bullshit!”

“It's also the people who have the least to lose who are always making that argument, y'know?” Daniele added. “But people who are actually trying to save their ass are not making this idiot worse so that punk will be better.” Later, Greer said she just refers to Priests as a rock band, so that “I don't have weird feelings about accidentally commodifying a subculture that benefits me way more than it benefits the subculture.” (She specifically referred to 2013 trend pieces about “feminist punk” that helped boost the band’s profile, which had given them all some trepidation.)

“I think we isolated ourselves for a while out of distrust of not wanting to be used as a tool to sell the idea of counterculture or the image of it,” Mulitz said. “But if anything, through making this record we've come to learn that it's OK to let your walls down.”

Anyways, the old song-and-dance about anarchy and government pigs seems naive and disingenuous once artists reach a level of success where they’ve benefited from the system too much to sincerely wish to burn it down. Tom Morello, who made millions of dollars raging against the machine, probably should not have so eagerly compared Hillary Clinton to Donald Trump.

But Priests sing about politics in more nuanced, interpersonal ways that rise above “everything is fucked, everybody sucks” finger-wagging. “Nicki” considers the uneasiness of making female friends when patriarchy dictates how women should treat one another; on “Nothing Feels Natural,” Greer demands respect by wailing “If I walk a hundred days does it mean I get to say / You can’t talk to me that way,” repeating the last two words in a haunting loop. “Pink White House” is a nightmarish rundown of the soured American dream and its default options—“consider the option of a binary,” Greer yowls on end—that sounds even more prophetic when you consider it was written before Trump had secured the Republican nomination.

Beyond that, Priests partake in Washington D.C.’s proud do-it-yourself tradition: They pay their support bands a fair wage; they run their own label, Sister Polygon, which will release Nothing Feels Natural; (Dischord, the storied label founded by Ian Mackaye, helped with distribution and production); they looked up how to establish an LLC instead of hiring a lawyer to do it, even though it took them a year and a half. Daniele keeps a precise spreadsheet denoting every show Priests has played, how many people they drew, and how much they made, so that the band has a firm frame of reference when promoters and booking agents try to undercut them.

It’s this behavior, not the angsty sloganeering, that will resonate further and matter most while living next door to Trump. “We're trying to be an open book about—and really vocal about—standing in the face of that and wanting to connect with other people in the area and make other people feel safe to resist,” Mulitz said. Because regardless of how your music sounds, what could be more punk than choosing to play by your own rules in a rigged game—by demanding fairness and respect in a system built to deny both?

[featuredStoryParallax id="225121" thumb="https://static.spin.com/files/2017/02/DSC03905-1486053370-300x200.jpg"]

Over inauguration weekend, the atmosphere in D.C. was alternately welcoming and feral. “Make America Great Again” hats dotted the streets; the day Trump was sworn in, inaugural counter-protests were tear-gassed and 217 protesters were arrested. With images of shattered Starbucks storefronts and smoldering limousines flashing across TV, laptop, and cell phone screens the afternoon of the inauguration, it seemed eminently plausible that a band of disruptors could interfere at the Priests show later that night. Greer said a socialist organization had offered to provide a firmer security presence, though the venue’s management immediately rejected the idea. “I’m worried about getting shot,” she said with a laugh. (The band carries knives for protection, though they’ve never had to use them.)

Before the show, the band flitted about the Black Cat, preparing the space to host a protest. A table bearing leftist literature, and merchandise such a shirt bearing an illustration of Trump wearing a KKK hood, was set up in the back. Greer, who’d swapped a “VICE IS COPS” button onto her pea-green jacket for a simpler “NO,” taped a grid of posters into a giant banner, and hung it on the back of the stage with Mulitz’s help; Jaguar toyed with the amps before their sound check, which had been delayed by scheduling quirks. (Sadie Dupuis was caught in traffic, though she eventually made it.) Backstage, one of the night’s performers walked around strumming Van Halen’s “Panama” on his guitar, which was plugged into a portable amp he wore around his belt.

When the show started, a convivial mood took over. D.C. songwriter Jonny Grave joked with the crowd about their reticence to move closer to the stage at the beginning of his set. “I’m not going to bite,” he said, before they bunched up. Activist songwriter Evan Greer, who earlier in the evening had discussed her interactions with the newly freed Chelsea Manning, offered a set of rousing protest songs. “This fight didn’t start with Donald Trump,” she said. “It’s been going on a long time.”

Ted Leo and the Pharmacists, who were treated with veneration by the younger crowd, gave a vigorous speech about pushing forward before launching into a set of Bush-era fight songs like “Me and Mia”; Dave Longstreth, billed as the benefit’s “special guest,” went through stripped-down versions of his new songs under the rebooted Dirty Projectors name; Dupuis and Waxahatchee’s Katie Crutchfield delivered somber solo performances to rapt crowds. The show moved along breezily, maintaining a full crowd until just after midnight. (Ian Mackaye, forever the patron saint of DIY righteousness, was also in attendance.)

Just before eleven o’clock, Priests came on. Though they didn’t play longer than anyone else, and though their set came in the middle of the bill, they felt like the headliner; they received shout-outs from every performer for their work in putting the benefit together, and their set drew the most engaged crowd. They played “Right Wing,” an older song whose lyrics felt completely appropriate for the occasion; they played three songs from Nothing Feels Natural, which sounded cavernous inside the club.

Their chemistry was magnetic and undeniable: Greer prowling the stage, Daniele whipping the drums while bearing a wide grin, Mulitz providing poised support, Jaguar wielding his guitar like a weapon. They looked like the rock band you’d want to look to for inspiration in this insanity of Trumpland, for however much that could matter.

Before Priests began their set, Greer gave a short speech. By that point, bands had been playing for four hours, and were scheduled to run until 1:30. “Are you feeling exhausted?” she asked. “The fact that you could come be here means a lot.” She announced that the sold-out show had raised more than $12,000 to be donated to the charities—a small, but valuable amount of money that wouldn’t go to waste. “This is the way forward. This is where we can put our efforts and fight this, because we can fight this and we will.” It was only the first day, but the mood was hopeful.