In one of many houses in a row on a winding downslope in northern Philadelphia, Baroness are jamming in the basement. On the front porch where I’m waiting to be let in — I texted that I had arrived, but unsurprisingly, my alert has gone unheard — a delivered-but-unnoticed box of musical gear lies next to a discarded pink toy convertible. I can hear the low rumble of the band (minus guitarist Pete Adams) running through a couple of songs, but otherwise, the stillness of the sunny November day in the suburban neighborhood is stunning. I’m more likely to attract attention for my milling around the house’s entrance than the group is for the stadium-ready racket emanating from below.

Though you wouldn’t know it from the outside, this is the Baroness compound — the home base and practice space for one of the biggest crossover acts in metal. The band drills in the basement, next to the washer and dryer, and several floors up, lead singer and lyricist John Baizley designs the group's visual artwork in his personal studio. Somewhere in between the basement and the studio, Baizley also actually lives in the house, along with his wife and their 6-year-old daughter, while his bandmates routinely schlep to Philly — Adams driving six hours from Virginia, bassist Nick Jost and drummer Sebastian Thomson taking public transportation from New York — to write, rehearse, and crash in the living room.

The quartet’s other three members are a regular-enough presence in their frontman’s home that they’ve become surrogate uncles to his daughter. “Nick teaches her piano, Seb does math with her, Pete draws pictures with her,” Baizley recounts. “I get too romantic about it, but the band is like a family.” And his family is part of the band, too — his wife is invested full-time in all things Baroness. “She just helps me administer all the band stuff... I can’t keep up [on my own],” Baizley says. “She’s part of the chaos in this house.”

As we speak in late Autumn, that chaos is focused around the December release of Purple, Baroness' massive and majestic fourth album, and its accompanying promotional tour of smaller venues across the U.S., which the band will embark upon at the end of the month. Over their decade-plus career — the group formed in Savannah, Georgia, in 2003, though Baizley is the only remaining original member — Baroness has built a fanbase much larger than they can play to in 200-capacity clubs. This tour will be a throwback to their road-tripping days behind their earliest EPs and first few albums (2007’s Red and 2009’s Blue), before they expanded their audience with 2012’s less obviously metal Yellow & Green, the double album that attracted some of the strongest reviews of their career, and debuted at No. 30 on the Billboard 200.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/DnYO7iQfQDQ

Aside from the pressure of following up their breakthrough effort, the band has added on the burden of releasing the album themselves, via their newly founded label, Abraxan Hymns. So with weeks remaining before Purple hits stores, Baroness are still deliberating last-second questions of packaging, and coordinating with retailers. (The band insists that they had no issues with Relapse Records, the iconic metal label that put out the first three Baroness albums, but merely wished to ensure creative autonomy at this point in their career: “I’m terrified of major labels, man,” Adams summarizes in a later phone conversation.)

The process appears to weigh heavily on Baizley, whose droopy eyes, nervous hand tics, and manic conversational style make you wonder if he’s slept in the last month. “I haven’t slept at all this year,” he blankly clarifies, and it’s hard to tell how much he’s exaggerating. Objectively, he can acknowledge that a perpetual lack of slumber isn’t a sustainable lifestyle (”And I’ve been doing it for 15 years!”), but this is clearly something of a natural state for Baizley, whose skinny frame and unwieldy beard suggest an obsessive who regularly skips meals and personal upkeep while in the throes of artistic tinkering.

That perception is hardly downplayed by Baizley as he shows me the scores of demos — instrumentals, first takes, and other rough drafts — that he’s recorded over the years for the dozens of songs that have eventually wound up on Baroness LPs. Not only has he saved and organized all of these on his computer, he’s given every collection its own fake title, cover art, and even artist aliases like “Michael McDonald Fagan.” I half-jokingly ask if he’s saving these early editions for bonus tracks to the far-off (but surely inevitable) 20th-anniversary reissues of the first four Baroness albums, and he zero-jokingly answers that a lot of them could be.

As much as he’s consumed by his own music, he may be even more voracious consuming the music of others. He tells me he’s listened to at least one new album every day for the last four years — schooling himself both on older artists he never understood, like the Beatles and the Eagles, and fresher albums by artists out of his musical purview, like Grimes and Ryan Adams. He also says that, despite being a 37-year-old family man, he still tries to go to four concerts a week, seeing acts of all stripes. “It’s my job to not lose touch with what people are doing,” he explains.

By Baizley’s own admission, Baroness probably couldn’t function with four members as meticulous and compulsive as he. “I’m just a weird ball of energy,” he says. “What’s needed [for balance] is Pete.” Adams, lead guitarist and backing vocalist, is indeed a stark contrast to his more frenetic bandmate, who he’s been friends with since they were teenagers. Even though Adams is responsible for a healthy percentage of the band’s artistic vision and the label's day-to-day, he’s far calmer and more casual when discussing group affairs, he prefers the honesty of first takes to the fineness of hundredth takes, and he draws lines between business and personal where Baizley will not. (Does he share Baizley’s tendency towards sleeplessness? “No, I sleep — that’s what I do well,” he responds. “I need eight hours, man, that’s what’s up!”)

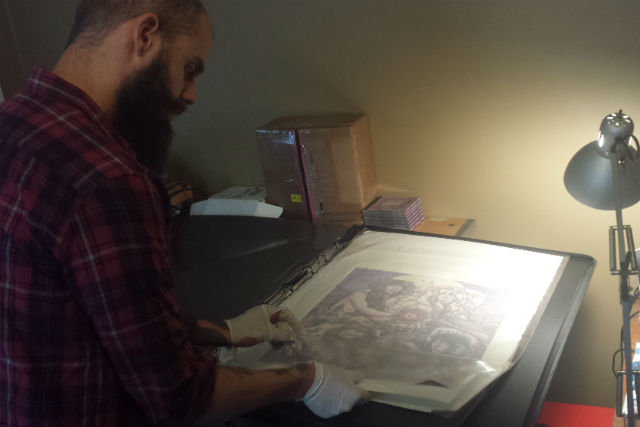

[caption id="attachment_id_176986"]  Andrew Unterberger[/caption]

Andrew Unterberger[/caption]

The most obvious rewards of Baizley’s relentlessness come with his artwork, which he’s designed not only for every Baroness release, but also for LPs by peer shredders like Torche and Skeletonwitch. The lead image for Purple is an incredibly detail-rich painting of four nude women — his longtime visual archetype of choice — adrift in an appropriately purple-hued sea of flora and fauna. The artist says it took somewhere between 200 and 300 hours to create, and required a great deal of research into mythology, philosophy, and theology. His investigation into religion is particularly necessary because of Baizley’s lack of personal history in the area. “I’m most definitely an atheist,” he says. “Especially after 2012.”

The year 2012 should’ve been Baroness’ biggest and best, with Yellow & Green dropping that July to near-universal critical acclaim and first-week sales that were the best in both the band and Relapse's history. But the triumph was cruelly short-lived. On August 15, barely a month after the album’s debut, Baroness and five touring crew members were heading down a particularly steep hill in Monkton Combe, U.K., when the brakes on their bus failed, and the driver lost control of the vehicle. The bus went through a guardrail and a cluster of trees before becoming airborne, falling more than 30 feet to the ground below. (“We had spent enough time in the air to appreciate, make peace with and accept a fate we thought inevitable,” Baizley later recounted.) Miraculously, all nine souls on board survived the crash, but the band’s then-rhythm section — bassist Allen Bickle and drummer Matt Maggioni — both had fractured vertebrae, and Baizley suffered a broken leg and his left arm was shattered so badly that it nearly necessitated amputation.

Baizley remained in an English hospital for two weeks recovering, and then another couple of weeks immobile with his family in a U.K. apartment. The toll on the band and its frontman was tremendous — not only physically, but financially. Because of medical expenses and the cost of recuperating overseas, the windfall Baroness should have seen from Yellow & Green’s success had been completely wiped out. “We were given good advice [from our management] early on, which was, ‘You guys are screwed,’” remembers Baizley. “What they were saying was, ‘This work — you’re not going to see the fruits of your labor.’” Even today, the band remains in financial straits — Baizley doesn’t own the house that serves as the Baroness compound, and he says the rent is more than he can really afford.

In the meantime, the four members of Baroness had to decide if they were even going to continue on together. “Within the first week or two, after the bus crash, I was definitely very concerned about the band,” says Adams. “I was just kind of like, ‘Yep, that’s it.’” But he was heartened by his first conversation with Baizley — who says he never questioned the band’s future — after the frontman was finally able to get out from the haze of medication and overwhelming pain he’d been under. “[I was] like, ‘Well, what do you wanna do?’ And John was like, ‘I’m gonna get better,’” Adams recalls. “And he was like, ‘What do you wanna do?’ And I was like, ‘Well, yeah, right. Let’s not end this band.’”

https://www.youtube.com/embed/0fbK53mQ3Wk

But both Baizley and Adams knew soon after the accident that the group’s rhythm section was not long for Baroness. “I was pretty sure that Allen and Matt would leave,” the frontman says. “They seemed very shaken up by it very immediately, so it wasn’t surprising.” Neither of the remaining members held it against Bickle and Maggioni when they did leave the group in early 2013, saying that the combination of their injuries and their post-traumatic stress responses — Adams, a veteran of the Iraq War who says he’s lived with PTSD for 13 years, is particularly sympathetic — made their decision understandable. “It is what it is, and no hard feelings, man,” says Adams. “But, you know, I saw it coming right off the bat, and was prepared to replace people immediately.”

From there, Baizley and Adams say they got really, really lucky. Through mutual friends in the music industry, they tried out two prospective new members: Sebastian Thomson, drummer for influential Maryland krautrock trio Trans Am, and Nick Jost, a jazz-trained, all-purpose bassist. And when the pair of tryouts were over, Baroness were suddenly a foursome again — an audition process that was, by all accounts, shockingly simple. “I played with John, and then Pete showed up the next day to jam, and then we were just hanging out,” Thomson says. “And then they’re like, ‘Well, you know, we’re going on tour next year, blah blah blah,’ and I was like, ‘OK…’ It was that sort of casual.”

The new members slotted into the lineup with disquieting ease, strengthening the outfit's four-way assault and adding new elements of jazz and electronic music from their diverse backgrounds. And though half the band now shares a particularly gruesome history that the other two have no part in, Thomson says that maybe the “fresh element” he and Jost bring is what’s needed in a group that’s been through so much. “I think it might actually be a plus that Nick and I don’t understand every single thing that’s happened to them,” he suggests. Adams would probably agree, as he seems elated with the current state of the band. “I think the most important thing was going, ‘OK, well here’s what we needed to fix, and this is what we want, if we’re gonna get two new dudes,'” he remembers. “And damned if we didn’t find them! It just worked! And we didn’t even f**king try!”

Baroness would try out their new roster with extensive U.S. gigging in mid-2013, a set of dates “to prove to people that we didn’t disappear.” The tour was a bittersweet one, given the calamity the band was still reeling from, but it was a successful trial run and a particularly validating experience for Baizley. “The mood and the energy and the vibe, on and off stage, was so good,” the singer says. “We still felt proud of the process of making [Yellow & Green], creating it, putting it out, and also very happy and proud to have been able to survive and get through the thing that just easily could have been the end.”

Adams knows Baroness has miles to go before they sleep, but he refuses to dwell in the past. "Man, we’ve got such a good thing going on right now that it’s really hard to look back," he says. ""

[featuredStoryParallax id="176983" thumb="https://static.spin.com/files/2016/01/Baroness-purple-cover-story-2-300x133.jpg"]

Baroness may have lucked into surprising stability in the years following the bus accident, but such peace is still hard to come by for its frontman. Baizley has scars that simply aren’t going to heal, the most literal of which runs almost the entire length of his left arm. “There’s giant metal plates in there and there’s a ton of nerve damage, and it really feels like I’ve got this part of my arm dipped in a bathtub with a toaster oven in it,” he says. “It never goes away. There’s been no break for three years.” Making recovery even trickier is the necessity for Baizley to medicate with painkillers, perilous waters for the singer, who once dropped out of Rhode Island School of Design with substance abuse problems. “It was a problem that I thought I had seen the last of,” he says.

If that sounds bad, it is — and every question I ask Baizley about the accident and the permanent pain in his left arm makes his outlook sound bleaker and bleaker.

Is the accident something you still think about when you wake up in the morning?

“Not when I wake up in the morning. It’s what keeps me up at night, unfortunately.”

How long did it take for your injury not to become distracting?

“Um, I don’t know. How many days has it been since the accident?”

Well, how long did it take to learn to play with it, live with it, sleep with it?

“I mean, I still am learning. It’s not easy.”

After that last one, he continues:

“It’s evolved because the really, really unfortunate side of my particular injury is it gets worse. Over time it gets worse. The pain level increases and the mechanical difficulty increases, so that’s what I have to stay positive about, you know? ‘Cause there’s no good outcome. There’s no real light at the end of that tunnel. There’s only acceptance, and acceptance is very, very difficult. It was really easy for two years. Because for two years I was just thankful that they didn’t cut the thing off, when that was a discussion. Now, for the past year, for whatever reason, I can’t stop focusing on the next five years, the next ten years, the next 20 years, and feeling like this... I don’t look forward to it at all.”

As despairing as all this reads, the remarkable thing about Baizley is that against all odds — the really astronomical ones, which he keeps spelling out for me and for himself — he never comes off as defeated. He talks without bitterness, regret, or blame, even as he openly discusses his chronic misery as a permanent crescendo of hurt, so much so that I always expect him to transition to the positive part of his prognosis, the part that’s giving him hope, and he never does. He’s not self-pitying about his merciless situation, just tragically self-aware.

“Trauma’s tough,” Baizley says. “It just leaves a big, nasty, permanent welt on your subconscious, and you’re better to recognize it."

And if there is a silver lining to the cloud that’s hung over Baizley for the last three years, it’s that it helped inspire his best album. Recorded over six weeks at longtime Flaming Lips producer Dave Fridmann’s studio in Cassadaga, New York, Purple — the color of bruising — isn’t as outwardly ambitious as Yellow & Green. But at only ten tracks and 44 minutes long, it’s the band’s most coherent LP, and their strongest collection of songs yet. Plumbing unprecedented sonic depths for Baroness, Purple flows like Pink Floyd’s best ‘70s works, one track leading inexorably into the next, the atmosphere of the production as compelling as the intricacies of the songwriting, a concept album without a clear concept. “I think it’s the best record we did, ‘cause we covered more territory in 44 minutes that we have on all of our records,” Baizley says.

If there is a unifying thread to Purple, it’s the accident, of course. The album hardly plays like a narrative of the crash and its fallout, but the tragedy is unmistakable within the oblivion of “Try to Disappear,” the suffering and healing of “Chlorine & Wine,” and the redemption of “If I Have to Wake Up (Would You Stop the Rain?).” Baizley says the latter song — the closest thing Baroness has to a “Wish You Were Here” — hits such raw nerves, his wife can’t even listen to it. “‘Wake Up’ is essentially a love song for my band, my crew, my wife, and the people who were there immediately,” he explains. “It’s just the best way that I have of thanking them.”

Purple is also a logical deepening of the stadium-rock grandeur that Yellow & Green broadcasted, much of it miles away from the Southern sludge that populated so much of Red and Blue. Appropriate for an LP with a lead single titled “Shock Me,” Baroness now sounds more like KISS than Kylesa, Baizley and Adams’ dual riffs riding the lightning, while the new rhythm section shakes the Earth underneath. It’s no less pulverizing for its accessibility, with “Kerosene” and “Desperation Burns” blistering as much as any past rave-ups, but with the emotional catharsis of “Shock Me” and “Wake Up” finally giving the underground titans the kind of anthems that could play on classic rock stations 20 years from now.

It’s been a dramatic enough expansion for the group that many fans have deemed Baroness no longer a metal band. It’s not ground that Baizley gets defensive over. “It’s not a metal record,” he says of Purple. “It’s a record that has elements of metal, and maybe an energy that is metal.” He acknowledges that the band is in a weird place musically and demographically: too heavy for the alt-rock stations and too indie for the metal stations, too big to be underground but not big enough to be mainstream. But more important to him than Baroness not being considered metal is Baroness not being considered any genre at all. “If there is a point in being in this band, it's that none of that stuff really matters,” Baizley says.

More than anything, Purple sounds like a triumph — a band haunted by a stormy past, peering into a foggy future, and deciding to put their heads down and plow through. “Trauma’s tough,” Baizley says. “It just leaves a big, nasty, permanent welt on your subconscious, and you’re better to recognize it and talk about it, I think, than to suppress it. And so doing a record that has elements of addressing that and elements of moving beyond it — but ultimately has a sound that we feel is energized and triumphant and overtly hopeful — for me, is a huge accomplishment… So, thank you, Pete, Sebastian, Nick for dragging what could have been a real bummer and turning it into something that celebrates life as opposed to just pointing the finger at the shadows.”

And though Baizley knows his condition won’t improve anytime soon — he says he could have surgery someday to get some of the wire (or even the titanium plates) in his arm removed, but any such procedures would immobilize him for longer than he’s OK with right now — he’s taking his hydrocodone, and he plans to use January to finally get some of the rest he’s long deprived himself. “I’ve figured out a way to get [around] things that I’m not particularly comfortable with,” he says. “But, you know, I’m pleasant. I can laugh. I can do fun stuff. I can be nice. I’m not flying off the handle, and I’m not laying in bed all day.” He pauses. “Maybe I should lay in bed a little bit more.”

https://www.youtube.com/embed/hHPTd8RrDgk

In late December, I pile in with a couple hundred Baroness fans to the metal venue Saint Vitus, in Brooklyn, to see the final date of the band’s mini-club tour to promote Purple. When I visited Baizley at his house a month earlier, he was itching to get back on the road. “It’s torturous for me not to tour,” he said. “I am most comfortable and most at ease when I’m on the road.” I asked if it was hard for him to leave his family. “I mean, it’s hard for any musician’s family when they go. It’s also hard for some musician’s families when they don’t go,” he answered, laughing. Perhaps most incredibly, even after the 2012 crash, he said he still sleeps better on the bus than he does anywhere else.

From the moment Baizley smacks me in the chest on his way to the Saint Vitus stage, I can see the difference in him. He looks about the same as I remember him from a month earlier, but wearing a sleeveless Nails T-shirt and a look of crazed excitement on his face, he’s transformed from the overthinking workaholic I spent that Friday with into the imposing frontman for one of the mightiest rock bands on the planet. When he gets on stage, he raises his hands, and the audience’s hands instinctively go up with him. The band’s set is soaring and exultant, capable of filling a space about a hundred times the size of a small bar backroom in Greenpoint, and the crowd screams along to the Purple material as loudly as for older Red and Blue favorites. The foursome sounds every bit in lockstep as Adams had billed them in our earlier conversation, and towards the end of the show, the guitarist signals that Jost and Thomson’s indoctrination is now complete: “They’re not the new dudes,” he raves of the rhythm section from across the stage. “This is Baroness right here.”

[featuredStoryParallax id="176989" thumb="https://static.spin.com/files/2016/01/baroness-purple-cover-story-interview-4-300x133.jpg"]

It’s clear early on, however, that Baizley’s not at full vocal strength — his growl cracks repeatedly, and he confesses to the audience partway that “I’ve been on tour for three weeks and my voice is f**ked.” But he asks the crowd to sing along to help make up for his diminished power, and they’re happy to oblige; the gig is probably more memorable for the singer’s occasional vocal floundering. Later that night, I text Baizley to congratulate him on the show, and he responds that he had been nervous, having lost his voice earlier that day. I comment that there’s something to be said for showing a little frailty amidst the shredding majesty, and he texts back the simple statement: “We’re rock serfdom.”

I’m still not entirely sure what he meant by that. But my best guess is that he meant that no matter what level of commercial success or musical magnificence they elevate to, Baroness aren’t meant to be viewed as rock overlords, deigning to grace their constituents with their presence. They’re the band that, even after all that’s happened, still gets most excited by the rush of connecting with the audience, that continues to prioritize their DIY mentality no matter how closely they start to resemble the biggest bands in rock history. They might even be living next door to you in the suburbs, toiling away in the basement of a house they can’t afford.

Baroness aren’t metal. Long live the survivors of Serf Rock.