We sent Titus Andronicus singer Patrick Stickles to the Toronto stop of Riot Fest to cover the first Replacements concert in 22 years. His witty, wide-ranging, often-philosophical impressions are contained in the following 9,000 words. There is a somewhat more straightforward description of the show itself toward the end, but we suggest you absorb the full impact, which we’ve come to term within the SPIN offices as “Stickles Gets His Tonsils Out.” Audience footage from the concert can be found on YouTube.

I. Nowhere is My Home

A very long time ago, before you were born, there was a city, or two cities, really, in a very cold, very remote place, a place you’ve never been before and are unlikely to go. Into this cold and remote place, people just like you and I were born. Being born there, typically they would die there, and, in the interim, more or less try to lead decent, quiet lives, to embody simple and practical values, to provide for their loved ones and not hurt anybody. This tiny corner of the world would get few visitors, and those they did get were usually just passing through. The wide world was far, far away, off by some endless arrogant ocean, and of very little concern to anyone. With a thousand-plus miles of open space on either side, the people of these twin cities moved through their lives demanding very little and often receiving less, but never complaining, because they knew that, when all was said and done, they were essentially going to get what they deserved. So it was for the Common People, like you and I.

Also Read

Every Replacements Album, Ranked

Yet, they were not alone. Yr not going to believe this, but in those days, gods walked the earth, beings wholly unlike those you see today trying, and failing, to emulate them. They stood maybe ten or 11 feet tall, with long golden hair and elegant clothes of many colors, and by screaming and moving their hands a certain, mysterious way, they could have anything, or rather, everything. Periodically, these gods would gather their loyal subjects before them in some kind of cavernous or wide-open space, and with the mortals on one side and themselves on the other, elevated and illuminated, an elaborate ritual would be performed. There was smoke and bright, flashing lights, and noise upon noise, and as it all washed over the huddled masses, they would undergo a strange transformation, and the pain that seemed their birthright would float away with the smoke, even if only for a night. The gods seemed possessed with some kind of unearthly strength, some kind of insulation against the pangs and pricks of normal life, and, still more amazing, they had the ability to share it, however temporarily, with those who could not get it for themselves (like us). For this, the gods were adored in a way that you have never seen anyone adored, and when the ritual was complete, the gods would retreat back to their misty mountain where there awaited magic potions and piles of gold and silver and lavishly appointed banquets and eager virgins. They said they were virgins, anyway.

Amidst all the smoke and the lights and the noise, there amongst the mortals, stood four boys, young as you are now, one of them even younger, watching in wide-eyed wonder. These boys were remarkable only for their advanced ability to slip between the cracks of the system, to fall off the bottom of the social ladder. Beneath that ladder and after that fall, they found each other, grasping into the gaping infinite blackness of the Abyss and touching soft, warm flesh. Some were bonded by blood, all by boredom. Still, they were four faces among thousands and, love or hate as they may, still there was the Line and none had crossed it before and returned. It seemed unlikely that crossing the Line, moving from Ape to Overman, was a choice that one could make for one’s self. It was destiny, the divine right of kings, the natural order of our world. Maybe it wasn’t fair, but the scales remained balanced and basically everything shook out all right, more or less, most of the time, or so the boys were told, by parents, preachers, principals, police (for practical purposes, people of power).

They were laughed at, the way yr laughed at now. They were denied attention and affection and fellowship. Cast out from society, they found sanctuary and solitude beneath the earth. In this underground lair, the air hung thick with strange smells and loud noises, as the boys incanted the words and the rituals of the gods they had been watching so diligently and reverently, and in emulating these rituals, they felt a budget version of what they could only imagine the gods felt, the unimaginable power, the impossible freedom. On the surface, they were failures, losers, substitutes at best, smelling of dog breath. In the basement, they were taking care of business. “Tonight, there’s gonna be a jailbreak.” Not really, though.

They found themselves in the depths of the Void, completely cut loose from meaning or purpose. They were losers, and they would always be losers. Winning the game that the gods had played and won was not an option for these humble serfs, and they divorced themselves from their desire to rise above their station. Within the infinite blackness, nothing meant anything — their triumphs were meager, their hopes humble, their quest quixotic. They grieved for the lives they had known, for the rules that they had been forced to learn to love and to cling to for what sense of security one could hold in The Void. Like Ulysses, they were mere playthings of the higher powers, pawns in a game far beyond their control or comprehension, tossed about on a rough sea like a terrified tugboat. No better life awaited them. They were born into the life that they would die in, and the view from just outside the womb was not to be substantively different from the one just outside the grave. Everything was Nothing. Everything.

Everything, even… the rules? Fucking right, the rules! They too, the boys discovered, were arbitrary, absurd, created for their own sake by those who would preach the lie of the Greater Meaning to manipulate the weak and afraid. In the infinite blackness, what freedoms awaited our boys! God did not exist, and thusly, everything was permitted (I didn’t make that part up). It was all there for the asking, if one had the bravery to face the unspeakable, unthinkable terror of the Abyss.

It seemed, for a moment, that there was some crack in the wall which separated our boys from the world they had been told about, the world that they had been denied, and the faintest light was beginning to creep in. If only they had a hammer.

A thousand or so miles away, that hammer was cooling by the side of the furnace. Near the ocean, there were Others, and Others they were. Hair of bizarre, unnatural color. Holes where holes shouldn’t be, in apparel and flesh alike. Not a smile but a sneer. Not strolling but stalking. Not speaking but screaming. These Others had seen the gods, too, had stood before the altar but could not worship. Where others had opened their hearts to the gods and let love in, the Others opened up and let hate out. The gods were not perfect, infallible, untouchable beings, as the world had been taught to accept them. They were dirty fuckers. Boring. Pigs. Rubbish. The wool had been pulled over the eyes of the earth, and the Others thought themselves to hold the shears. The gods would be exposed for what they were — charlatans and carpetbaggers, preying on the weakness of those who could not know any better, dedicated to some kind of Great Swindle. The Others would tear down the temple, they promised, and build a new one, an altar to the Common People, where all would be received and loved. First, though, the old gods would have to die, and they would have to die amid screaming and whirling limbs.

It took a long time, but word of the Others’ plans reached the remote corner of the world that was home to our four boys. It was written in a crude hand on copies of copies of copies, or came in all-too-fleeting, two-and-a-half-minute (at most) bursts, concealed on sacred discs of severe scarcity which passed from hand to anxious, grateful hand. One of our boys (the last to join the team, he who lurked unseen outside the window of the basement sanctuary with eager ear to marvel at the way these underworld dwellers attempted to steal the fire from the top of the mountain) claimed to understand, that the god-killer had been within him all along, slumbering. He had been changed, he believed, so let’s call him not Saul but Paul. The other three, especially the elder of the two brothers, were not ready. Life under the loving eye of the gods had been good — not great, perhaps, but good enough, good enough to not just throw away. The life they had known was more than just trash to be taken out, for now at least.

As word of the divine assassination plan spread through the community, more and more came to stand on the side of the Others, and it became more than a coastal phenomenon, an intrusion, an outside agitation. It became a part of the lives of those who had heard the call, and they began to assemble and develop an awkward infrastructure, or as they called it in those bygone days, “a scene.” It was free from the influence of those who worshipped the ocean, the money-changers who toiled and schemed a hundred stories above the capless heads of the hapless populace. There were those on either side of the great and indifferent ocean who saw the plot as a way to ascend to the level of, and replace, the old gods, but they had tried and failed. What the people of the twin cities were undertaking was not to be an escape, but more the planting of stakes.

As the community began to coalesce, a new church was raised, as promised, and the New Others would gather and share their hard-learned secrets. Money changed hands here, but it is said that more than that, ideas changed minds. At the center of all this was a man, not a boy, but a man, the man who acquired the sacred texts, collected the money, and directed the stream of information. He too loved and hated the gods — he knew that they needed to die, but that when they did, they also needed to be grieved for and remembered reverently. One fateful day, from forth the hands of our boys and into his came not even a disc but a small rectangular enclosure. When the man was able to coax that which was within it outside, he came to believe that the boys were the answer to the lingering dissonance between wishing the end of the gods’ reign and rightly giving thanks and praise. With his mind in the rapturous ecstasy of this new faith, he sought out the boys and prostrated himself before them. “Take my hands,” he said, “and let us do this noble work.” So they did.

The first transmission was little more, on the surface, than a facsimile of what the gods had done previously, translated into the new aesthetic of the others. Faster, more ruthless, undaunted by history or happenstance. Subtlety, grace, finesse — all these fell by the wayside. The ways of the old gods were distilled to their purest essence and shot straight into the mainline.

With the second transmission, the lessons of the gods all but faded into memory, if even that. Our boys fully committed themselves to the cause of the Others. It seemed a worldwide campaign was all too ready to begin, and the boys fancied themselves willing foot soldiers. For eleven glorious minutes, there were no finer recruits and the toppling of the ivory tower seemed to be just around the corner. “God dammit. God dammit. GOD damn.” Also, “Fuck School.”

By the time of the third transmission, our boys came to understand that the Others had done little more than put up a different sort of a prison, just another cage more suited to the new aesthetic parameters. The boys had set out in search of freedom and found only new rules. From that point forward, the death of the gods would not be enough, for when one god falls, two rise to take its place. Nothing less could be settled for than the end of a world in which a god could rise, a complete dismantling of the divine birthing apparatus. To this end, our boys discarded not only the rules of the gods, but the rules of the Others, alternately embracing one to spite the other and then vice versa. So did they open up the doors to their new world and let in anything, everything. Nothing was good or bad, thinking makes it so (didn’t make that up, either), so let us stop thinking and start acting. Succeed, fail, prosper, starve, live, die, whatever. It’s a hootenanny.

Word of their deeds spread far and wide. The boys traveled their broad land, leaving behind a trail of detritus like so many appleseeds. They lived in absolute squalor, all over each other. Many that met them were baffled, disgusted, insulted, offended, indignant, furious. They were punished for their efforts more than compensated, execrated more than they were praised. For every dozen new enemies they made, however, there would be one new ally, and if their enemies soon found new targets for their vague rage, forgetting the boys and their strange, disturbing ideas about life, the allies they made kept the fire burning long after the taillights had receded into the dark night. From town to town, Duluth to Madison, they lit tiny sparks, never daring to hope the burning could be an eternal flame. Way up in the sky, the spheres moved slowly, but surely. Far beyond the temporal concerns of our hopeless heroes, the banquet was prepared.

Such was the scene upon the arrival of the fourth transmission, which could not have more perfectly encapsulated the totality of the boys’ mission up to that point. All that they had tried to do before, they did now for real. If grieving for the old gods was painful, that pain met its match in the joys to be found exploring the new, wide-open landscape. Not only was anything possible, all was encouraged, from the highest to the lowest. They validated their choices simply by making them — nothing further was demanded or expected. The world wants to be what we want it to be, so we will let it be, and these words of wisdom will be not only whispered but also screamed. Bloody fucking murder.

Thusly did they hurl their love and their hate alike into the Void, into the open arms of its forgotten population. Obscured in darkness as they were, their numbers were unknowable, but as our boys laid out their feast, one by one, the abandoned and unloved took their first tentative steps out of the cave and into the light. First a few, then several, then many, many, many.

It was not long before the gods of that time took notice of our boys, saw what divine essence they could see in the ragamuffin gang, and began to believe that they may not have been the mere mortals they were painting themselves as. A gloved hand reached out to our humble heroes, and soon they stood where they had seen the gods standing a few short years earlier. The view from this vantage shocked and appalled the boys, and in the thousand eyes that stared at them in silent (or sometimes not so silent) judgment was a hideous reflection of the gods they had sworn to bury. For this, the boys lashed out at all within their reach, doubling down and spitting the judgment back in the face of those before them. Still, the taste of the divine nectar lingered in our boys’ ever-gaping mouths. It was sweeter than they had dreamed.

First they came with gifts. Then promises of greater power, control, and freedom. Then silver and gold. All this was laid out before the four boys. They looked at it and considered it, poking and prodding and probing it. In their eyes, it looked a lot like everything else — just a lot of nothing. Better than the life they had known? What’s “better?” Worse? What’s “worse?” Sorry, Ma. It’s life, and life only. Red light. Red light. Run it.

Then you were born, and even if we weren’t expecting you, we loved you more than you can know.

Three months later came the fifth transmission and the four boys had become four men, yes, even the littlest one. It seemed they had proved all that they needed to prove. Their mission had been something of a success — tiny little pockets of enthusiasm and faith had grown to budding groves of new possibilities. That work would continue, but someone else could do it. You don’t have to turn yr whole life over to this shit, right? We all deserve a little bit of peace and security, don’t we? We can come down off the cross now, can’t we? Surely we can find a better use for all this wood. Put up a T-shirt stand or something.

The ideals they had worked so hard to spread had become an albatross. The pursuit of them promised only further frustration. Paul was ready. He looked within himself and recognized the familiar god-killer, but beside him there was a new partner, with hands free of blood and alabaster skin. He looked to his left, and saw the elder brother, still intoxicated off the freedoms they had found underground (among other things), and though Paul still saw the value in keeping that first spark alight, he saw that two breaths upon that flame would blow out the whole thing, that chasing the dragon all the way down the path they had forged together would bring destruction and death. So the elder brother was cast out. He would survive ten more lonely and frustrated years.

Another man, who had never been a boy as far as we know, stepped into the hole left by the elder brother, and Paul had the safety net he needed to be the sort of high-flying, death-defying artist that he needed to be. Three more transmissions followed at fairly regular intervals, each more beautiful, in their way, than the last. The heroes of destruction had become constructive, they began to build rather than tear down. The men struggled and slogged to bring their new message to the people, only to find that the same people they had flummoxed so before were furious to find a new group of dedicated professionals where there once stood a motley crew of ne’er-do-wells, who lived only to validate the worthless dipshit we all find in the mirror. You can please some of the people some of the time etc. etc. (T.S. Eliot said that.)

It all came to an end ten years after it started, on Independence Day, beside a bell which showed the signs of being tolled too hard one too many times. As it was cracked in the pursuit of liberty, so too were they cracked. They had set out to exterminate the gods, then decided to become gods themselves, only to realize the metamorphosis was more pain than it was worth, and so they stepped back into the darkness that had been their nursery. They were never, ever heard from again

In their quest to be the worst, they became the best. In rejecting the pursuit of perfection, they achieved it. They were so much better than the real thing, they could only have been the Replacements.

II. The Hardest Age

This is the legend, as it was taught to me, when I was yr age. My education began at the CVS Pharmacy in Glen Rock, New Jersey, within the pages of a retrospective issue of a now-defunct print magazine. (Apparently, they still generate new content on the Internet, but fuck if I care to read it.) From there stared at me eight eyes, hidden behind shaggy mops and the hazy, momentary complacency of cheap weed and cheaper beer. They didn’t look like the Beastie Boys or Madonna or the Notorious B.I.G. or any of the other semi-contemporary gods in the preceding pages. Under their gaze, I was not seduced or coerced or intimidated.

That Christmas — it may have been either 2000 or 2001 — beneath the steadily decomposing tree, there were two carefully wrapped squares. Opening one of them, I found Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation. Read all about that in my review of that band’s inevitable “reunion.” Opening the other, I found those same four figures whose gaze had given me such a funny feeling a month or two prior. Now they were on a roof, and it seemed like a couple of them didn’t even know I was there, or if they did, could not be bothered to acknowledge me. “The door to our world is open to you,” they seemed to say, “but if you enter, prepare to do things our way, because we owe you nothing.”

If you know anything about my life today, even only that I am writing an article about the Replacements, then you don’t really need to learn much about my youth. Basically, read the first part of this article again, the part about being completely cut loose from purpose, adrift in the Void, and replace the four boys with just one — and that was me. I grew my hair long as a kind of forfeiture, my way of saying, “I do not care to rise up in yr sick society, so do not consider me for a promotion.” I did not realize it at the time, but I was a burgeoning manic depressive and a veteran Ritalin Junkie (— @sosoglos ). I was a product of the special-education system in our public schools and of a broken home. I lived a facsimile of a real life in a community set up to protect me from the colossal failures I was sure to achieve if left to my own devices, basically the real-life equivalent of bowling-alley bumpers. I had everything that one could ever want, and I came up with a newer, better way to kill myself almost every day. “Maybe tomorrow,” I’d say, turning out the light.

That life which I had known effectively came to an end the moment that sacred square was pried open. Upon hitting the play button, I heard all the walls around me crashing down. G, A, B, A. Boom bap! Buh. Bah. Ba da buh bah. “How young are you?” I had thought a hundred, but all of a sudden, it seemed to be zero.

The song was “I Will Dare.” Superficially, it spoke to my romantic aspirations, dreams unfulfilled at that point, and furnished me with a number of good lines I could potentially try out on one of the more left-leaning girls at my school, should my balls ever drop (cigarettes were a few years away, but I had already grown fat off my fingernails). Deep down, though, I knew that Paul wasn’t talking to some Minneapolis floozy he would use up and then forget, the way that these rockers will do — he was talking to me, not to fuck me, but to love me? Certainly.

“Do not be afraid,” he seemed to say to me that magic morning. “I come with tidings of comfort and joy. The world that you have known is not the world. It was created to subjugate and anesthetize you. There is another world out there which awaits you, and I am going there. I can not promise you safe or easy passage, but we can get there together. There will be times when you will be afraid, but you will never be alone. The other world is right under our noses, right now. Meet me anyplace. Anywhere. Anytime. I don’t care — meet me tonight. If you will dare, I will dare.”

And so it went. With the final tonic chord still ringing in my ears, the opening count off of “Favorite Thing” and its attendant unison bends shocked me out of the warm comforts they had just been offering and back into the familiar(-ish ) territory of my contemporary favorites (Sex Pistols, Rancid, etc.). But they were not claiming “no feelings,” they were telling me I was their favorite thing. Before long, they were “coming out,” and the juxtaposition of the initial hardcore blast (Minor Threat was just a commonly observed t-shirt on the VFW scene at that point) and Paul’s “one-handed piano” (they just don’t write liner notes like they used to) spit in the face of punk orthodoxy (“We do this, but not this!”), the loogie landing like a four-four slug. Next thing I knew, the bass player was getting his tonsils out, and never had the terror of a doctor’s visit (a very familiar pain to such a maladjusted and diseased, but affluent, young man) sounded like such a gas (it would sound like even more of a gas later that same year, via “Take Me Down To The Hospital”). Within four tracks, the Replacements had covered more ground than I heard another band cover on their entire discography, and without the slightest scent of (cover yr ears, kids) effort.

I would forget all this immediately, with the twinkling, spartan intro of the fifth track. Over a jaunty, but weary, oompah and a patiently brushed snare, I heard something I had been waiting to hear for 16 years. Without fully coming out as a transgender, I can only say that my entire life, I have been alienated from “masculinity” and saw no future for myself in the moves of men, the way that they want to fuck everything. I knew then, without being able to articulate it, that there was one gender which had the power to create life, which could commune with the earth and the moon, which was empowered to not deny their feelings, casting them aside as childish trifles, displays of weakness and denials of virility, but to embrace them and validate them and trust them; and that the presence of my disgusting, protruding penis denied me access to this world and shackled me to the gender which can create nothing but death. I was too terrified, too ashamed, to put these things into words. After all, the other boys at my school loved nothing more than playing football and chasing “pussy” and dominating the field which lay before them, so what was I, some kind of fucking freak? And so I kept a lonely vigil over my earthly prison, the Wrong Body, and no one knew. Or so I thought.

Paul knew. “Mirror image see no damage, see no evil at all,” he told me, knowing what I faced every morning as I was made to brush my yellow teeth. “Kewpie dolls and urinal stalls,” he assured me, “will be laughed at the way yr laughed at now.” The other world is still on its way, he seemed to say. It Gets Better. You may not believe me now, but do me a personal favor, and don’t give up. The other world might arrive tomorrow — maybe it will arrive in a year, or ten years, or 50 years, or maybe never, but you are never going to find out if you don’t survive. I know it is hard, I know how much it hurts, just to look yrself in the face, and I know that the End of Suffering is so, so tantalizingly close, that it comes down the street with every bus, that it’s just beyond the edge of every roof, in Mommy’s medicine cabinet right this second, but a reward awaits you as well that you can not now conceive of. I’ve seen it, I swear. Today is hard, but you don’t know what could happen tomorrow: “Something meets boy, something meets girl / They both look the same, they’re overjoyed in this world.” They’re out there waiting for you, just like yr waiting for them. Get out there and find them. Find me. Anyplace, anywhere, anytime. If you will, I will. “Jefferson’s Cock.”

Then they covered KISS. I don’t think I need to say anything else.

III. God Damn Job

Okay, it’s 12 years later. I have tried my best to absorb all the aforementioned lessons and apply them to my own life and work. Most of the architects of the alternative universe which I had tried to make my home, who had been off in exile in the wilderness, returned, in glory, to find the seeds they had planted in full bloom from sea to shining sea and beyond. I saw the Pixies hailed as conquering heroes on the stage of the Hammerstein Ballroom, and watched as all my reservations about the wider world’s ethical implications dissipate in a thick fog of hits on hits on hits. A few years later, the pinnacle of my “suck-cess” as a musician (I’m a musician) found me on the summer-festival circuit concurrent to the Second Coming of Pavement, which enabled me to see them three times in three different countries for free, and count myself the most blessed man to ever walk the earth for yet another reason. It was only last month that I stood in the back of a long skinny rectangle of a room in Williamsburg, watching a band calling themselves Black Flag, and counting the seconds between “Nervous Breakdown” and when I would be allowed to leave. In so doing, I watched artists who had built their kingdom on the undeniable fruitlessness of their efforts, who had promised me that being a total loser was not only as valid as being a winner but actually preferable, not only erase their gambling debts, but become millionaires. (Maybe not Black Flag — you probably don’t get to be a millionaire playing at the Warsaw, even for two nights.)

Part of me had always wanted Stephen Malkmus to be a millionaire, believed that he deserved it far more than some fucking football player or quack doctor, and yet, I could not reconcile the idea that telling everyone you could give a fuck about a million dollars had somehow become a real way to make a million dollars. They had built a world on the notion that you didn’t need to play by the rules of the wider world, a world that looked to me like the home I had always wanted. Then they revealed that when you get to a certain age, that world starts to become more of a nice place to visit than somewhere you want to live. A door open for Pavement and the Pixies and Black Flag, a door to the world which had been denied them in their heyday, and so they passed through, because how could you not? It was “Debaser” and “Gold Soundz” and “TV Party” that had opened that door, not the Everything Industrial Complex, their medicine which had created the opportunity rather than their poison. It seemed, to some, as though “we” had actually won, but it seemed to me that in winning, we had lost. The old gods were dead, and in their place, new gods stood, with the blood of their predecessors still dripping from their claws and fangs. The rules of Bachman-Turner Overdrive and .38 Special and Grand Funk Railroad were gone, and in their place, a different set of parameters as to how you must play the guitar and how you must dress and the funny, no-fucks-given things you must say into the microphone between tunes. Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss? In every meaningful way, probably.

Into this cluttered arena now stroll the Replacements, and from the initial announcement of the Songs For Slim charity EP, the Bullshit Detector hasn’t stopped screaming, and neither have I. Okay, okay, yes, it is a grave injustice that a gifted and wonderful man like Slim Dunlap cannot afford the medical care he so desperately needs, and it is right and noble for Paul Westerberg and Tommy Stinson to put the petty stuff (but hopefully not the Petty stuff) behind them and cash in what chips they may still hold in an effort to be there for one of their own. I mean, fuck, Paul was there for me all these years, why shouldn’t he be there for Slim? The actual sounds that were recorded were drowned out by the flapping of lips, and upon listening to it for the first time in the So So Glos’ van (did you look them up yet? Stop reading this shit and get on it), it went in one ear and right out the other. Following Fear and Whiskey by the Mekons, the world definitively did not need another cover of “Lost Highway,” and even a dumbass like me knew that. I have to admit, however, that for three or four glorious minutes, the magic did come back, and once again, Paul was able to sweet talk a cute girl and make an effort to assuage my fears at the same time. “I’m not saying I’ll be true,” he told me, knowing, and likely sharing, my reservations, “but I’ll try.” I suppose that was all he ever asked of me, just to try, so maybe I should offer him the same respect now.

Or not, for once the Save Slim coffers were filled, the Replacements Inc. apparently came to quite a realization. I can almost hear them now, somewhere off in the recent past. Cue the wind chimes.

Paul: “Can you believe all the magazines and websites and shit that are picking up this Songs For Slim story? People really still remember us!”

Tommy: “I know, right? I am pretty used to this attention by now, being a member of Guns N’ Roses and everything, but people talking this way about the Replacements? Sure wasn’t that way last time we were playin’, was it?”

Paul: “Fuck no, it wasn’t! A lot’s changed since then — the goons we used to run around with are getting paid out the ass for doing the same shit we couldn’t get arrested for back in the ’80s!”

Tommy: “Yeah, you know, when we started this, I thought we could make a little money to help out Slim, maybe have a few laughs, but I didn’t think it was going to get this big!”

Paul: “Yeah… how big do you think it could be?”

It is a few months later now, and it is big. Big Big. Like headlining-those-summer-festivals big. Like Pavement big. Like million-dollars big. Merely by announcing that they were throwing their hats back into the ring, the Replacements became, in an instant, probably a hundred, if not a thousand times more popular an “active band” than had ever existed under that name with any of that personnel. The world that they had worked so hard to make so inclusive had expanded to the point where it could elevate its most revered forefathers to, or perhaps even beyond, the status of the titans whose arrogance had at once emboldened and enraged them.

It is for this reason that I have come to Canada, where I now sit. It turns out, not that I knew before, that there is such a thing as Riot Fest (Riots on the streets of Denver / Riots on the streets of Chicago / Riots on the streets of Toronto). The powers that be behind this brand apparently were able to load a sufficiently large bullet that, upon its firing, was able to shatter the glass wall which kept the Replacements, hard-working rock’n’roll band, in the past and sent them hurtling into the present (the future??). What was the price tag on this bullet? I could not say, for sure, but I have got a feeling that it was not the only one soaring through the same air. Surely Coachella/Lollapalooza/Pitchfork Festival/so on/so forth prepared some sort of budget that they hoped would allow them to scoop up some of the residual cultural capital this fast-moving train was sure to leave in its wake. The Replacements, however, are not Red Hot Chili Peppers or Radiohead or even Phoenix, and putting them up on the big stage at the big hour probably seemed like an even better crapshoot than the reunion must have seemed to the band — for the bigger brand names I just mentioned anyway. If I had to guess, I would say that the Riot Fest administrators figured they were never going to be able to afford to pull a Radiohead, but maybe if they blew most of the money they had, they might be able to get the Replacements and get their first (only?) U.S. shows. Good plan? Shit, I learned what Riot Fest was, didn’t I?

I am not going to get into too many details, but August 2013 was just about the most stressful, exhausting month of my life, and this Riot Fest I speak of happened to land just between the temporary conclusion of my many big-city concerns and the beginning of a lengthy American tour. (Hey Paul, Tommy, the other two — bands still do this!) Rock to the left, hard place to the right. Stuck in the middle. It was not until 6 a.m. on the second day of the festival that my traveling companions and I made it to Niagara Falls for a five-hour nap. We crossed the border that afternoon.

Upon our arrival, the universe spoke, not once but twice. As we walked from the car, I made the effort to accept that I did not have that thing which makes rock’n’roll and everything else so much more fun and pacifies the ghosts so effectively, but which the border guards would really be unhappy if they found (y’all know what the fuck I’m talking about). And that, at my luckiest, I was going to have an opportunity to buy a headache, but nothing more. It was then that I cast my eyes upon the ground in the dejected fashion of a Charlie Brown and, sure enough, there it was, fallen from the pocket of a careless punter. Okay, universe. I hear you.

Still the universe, in its benign indifference, did not rest, and soon our ears bent to the sound of a stranger, though really a neighbor (Bed-Stuy, do or die), who had come into possession of two tickets he could not use and recognized our party as the people best prepared, at that moment and that moment only, to take them from his hands. So we did, and it was a good thing too, since a certain editor’s promises of multiple passes would be dashed moments later at the media tent. So it was that we three travelers held three tickets. We went through the gates and nobody looked in my shoes.

Over the next hour or two, we mostly sat around and squandered our chance to see the Weakerthans before an adoring Canadian audience. Whoops. In this time, I took the opportunity to stalk a couple of people who had gone out of their way to identify as Replacements devotees (thank the universe people still haven’t learned that “Don’t wear the T-shirt of the band yr going to see” rule, which is bullshit anyway) and get in their grills. Only one of them accommodated me. Dave. His favorite album? Tim, the album on his shirt (albeit a patch of the Japanese import). Why? The songs are the strongest. So then, Dave, you’d say that the ideology of the band is secondary to the practical matters of their craft and artistry? “Rock and roll ideology is, for the most part, pretty bullshit,” he told me, “and you can see, even in the Replacements’ history, how lives get ruined from believing in that. “Not just ruined, but ended,” I responded. “Yeah.” “That’s pretty fair.” It was. #Bob

IV. GIMME DANGER

We had to put all this to the side, however briefly, to pay our respects to the band they nowadays call Iggy and the Stooges. You may have heard them called the Stooges, and in the days and weeks leading up to the festival, that is what we called them. When you read about them in the books, they are the Stooges, but there is no such company as Stooges Inc.

My apprehension was on full-blast as I watched an anonymous man set up an enormous bass rig for Mike “Jam Econo” Watt, late of the Minutemen. Even he, possibly punk’s most righteous but least self-righteous living saint, could not shut the door to the world Iggy and the Stooges invited him into, and furthermore, as he moves into his fifties, he can hardly be expected to be responsible for 160 inches of speaker all by his lonesome. A tiny part of me died watching that man, whose name I will never learn, let alone remember, prepare the ritual for Mike Watt, of all people.

I instantly forgot about that as the band executed the most thrilling stage entrance I had ever seen. In what felt like milliseconds, the house music screeched to a halt, Animal House-style (new In & Out Burger off-menu option?), and the roadies, who seemed to be just idly tuning the guitars, turned to face the previously unseen men now running at them full speed. James Williamson and Mike Watt leap into the straps that waited for them, and before anyone even knew what was happening, they were unleashing “Raw Power,” and in the face of raw power, concerns about the relationship between art and commerce are difficult to focus on.

In the second song, though, I am given pause, for it is “Gimme Danger.” Iggy demands it as he has for 40 years, and it sounds quite persuasive as the words fly from his eternally lean body, and yet, is it really what he wants? I have a good recipe for “danger” — fire all the people you hired to keep you out of a dangerous situation. All those systems you have in place to prevent you from falling on yr face in front of thousands of people? Throw them away. Pull away the net, and then we will have all the danger we can stand, and that sounds like a great idea until you realize, as these stooges have realized, that people don’t pay 70 dollars to stand in a dusty field and watch an old man flop. So they won’t flop. They can’t. With this much money on the line?

“We don’t believe in nothing!” the man who holds Jim Osterberg’s birth certificate screams at no one and everyone. We don’t believe in free-market capitalism. We don’t believe in punk, either.

The one-two punch of “I Wanna Be Your Dog” and “No Fun” seems to bring the set to a logical conclusion, and Iggy’s persistent cries of “fucking thank you” support that notion. A wave of applause greets the last chord, just as a wave of boos greeted the Sex Pistols’ cover version at the conclusion of their “last-ever show,” at San Francisco’s Winterland some 35 years ago. Just in case anyone had the feeling they’d been cheated, though, Iggy takes his ovation and then turns to his bandmates (his employees?), saying, “We can do one more…’The Passenger?’ I can do that one…okay, ‘The Passenger!'” With that, the iconic chords emanate forth from Williamson’s massive stack, and those assembled are thrilled to hear a song they know. Even if they don’t know it, when the bright light is shined in their eyes for the first time of the day, in the first minutes of twilight, they understand that the lyrics to the chorus are “la la la,” and like the studio audience waiting for the “Applause” sign to come on, they oblige. Loudly.

At this point, I think, Iggy Pop has got to be the most stuck-up asshole ever to be credited with inventing punk, and closing this ‘Stooges’ set with his solo hit the most egregious rock-star move imaginable. Typical big-business bullshit. I am so thrilled to be proved wrong, when I hear a riff I never thought I would hear coming out of a PA this size. Could it be? It couldn’t be. It is. “I GOT A COCK IN MY POCKET AND IT’S SHOVING UP THROUGH MY PANTS! I JUST WANNA FUCK YOU AND I DON’T WANT NO ROMANCE!” Wowza.

“Yr Pretty Face Is Going To Hell” follows and seems like it surely is the true finale, but then the Stooges prove that they are most certainly the definitive American punk-rock band, too early for the real party as they were, as they conclude their festival set with a song from their latest release (“Just ’cause we want to”) called, yes, ‘Sex and Money,’ and it sucks every bit as much as you would fear it does. In sucking at this moment, the Stooges erase every doubt I had as to their intentions, and I am so proud of them for getting rich off of these sorts of shenanigans.

V. TREATMENT BOUND

Okay, full disclosure, I spent the last seven-and-a-half hours getting to this point and now I have literally 34 minutes to cover the whole Replacements set (time management, what’s that?), but whatever. So there we are, and we await the arrival of the band we have been dreaming of seeing for so painfully long. In this moment, though, I realize that the Replacements have honored their legacy exceedingly well, for one crucial reason. The band that I have studied more diligently than maybe any other artist in any idiom, that band is preparing to step onto the stage — and I have no idea what is going to happen. The first wave of Replacements acolytes knew the same anxiety. Standing before the empty stage at Maxwell’s or 7th St Entry or some obscure church basement, these pioneers could not be sure whether they were going to see the transcendent, life-affirming, American Rolling Stones they saw the last time, or the sonic abortion they were subjected to the time previous. In much the same way, I could not be sure if I was going to see the word made flesh, the ideals I had suffered and sacrificed so much to make the biggest part of my life, or a slick cash-grab, old men revising history one last time for a shot at the Hall of Fame. Evidence was strong on either side.

I watched in disbelief as a crew of not less than 12 prepared the stage. The fix is in, I thought to myself. They can’t flop, so they can’t be themselves. The thing that made them Great, not great, but Great, was the fact that they weren’t always going to pull it off. The drama that elevated the Replacements from bar band to American institution had its birth in the knowledge that getting all the way to the chorus was not a given. You had to watch them fail and fail and fail, and say to yrself, “Man, for such a great band, they really fail a lot.” And so you begin to doubt them and fear for them, and like the great tragedies of the ancients, you realize that if it were you up there, you would be shitting yr pants and flopping twice as hard. Those are people up there, mere mortals fucking up the same way you fuck up yr life. Catharsis, it’s called. Pity and fear. It is in the moment of this doubt, of course, that the engine roars to life, and before you can say, “color me impressed,” the greatest rock’n’roll band of all time is right under yr nose. This is how you achieve the sublime — not by being infallible or invulnerable, but by showing yr fallibility and sharing in the glorious moment where, by sheer luck of the draw, the universe smiles on you and you are, even if for only a second, more than what you were born as. That is the true spirit of rock’n’roll. Yr a fuck-up. Yr beautiful. Yr human. The Replacements, however, seem to be fully beyond human, and failure — at this level, with these stakes — is not an option.

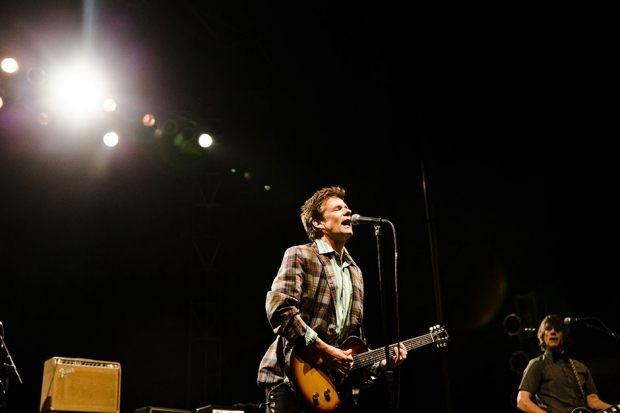

I cannot deny the smile which creeps upon my face as they emerge from the shadows, clad in the most garish “formal wear” they could find, just like old times, and yet, I am afraid. There might not be going home after this. The next time I put on Let It Be might not mean what it meant last time.

Paul steps to the mic. “We’re gonna play some old shit, if that’s all right.” Then they go into it, and they pop it off the same way they popped it all off, “Takin’ A Ride.” The minute that I realize this, I forget everything — this article, my home-life concerns, my professional woes, the greater meaning of it all, maaaan — and from beyond the grave, I heard the words of Bob. “One thing about music,” he told me, once again, “when it hits, you feel no pain.”

With that, I felt my feet leave the earth. The stage grew closer and closer. Maybe elbows rubbed mine. By the time of the chorus, I was fully ensconced, surrounded by people with whom I had nothing in common but the belief that, beyond what we were presently engaged in, nothing mattered. I was baptized in their sweat once again. “Stop right there, go no further.” Please don’t stop.

I could probably crank out a thousand words about every song in the set list, but I am staring down the barrel of 13 minutes right now, so I will simply relate this anecdote.

“Should we do ‘Androgynous?'” Paul asks into the microphone, though the object of his question is unclear. If the audience is unsure if they are that object, their screams of affirmation suggest otherwise. Soon, they are doing it. In that moment, the 28-year-old who worries about money and where he is gonna live and how he is going to manage all of his ongoing concerns ceases to exist and all that remains is a 16-year-old staring once more in absolute terror into the Void. All those fears, those pains, those aches and agonies, wash over me as that same twinkling intro, arranged for guitars this time (this is a fucking rock’n’roll show, okay? What’s a pee-yeah-no?), gently wafts across the field. I hear a familiar voice, a voice that has comforted me in so many dark hours. “He might be a father, but he sure ain’t no dad,” a few thousand lonely people form a chorus, and I realize, that in those moments of crushing loneliness, I wasn’t alone at all. We weren’t alone, only dispersed, and now we are together.

But Paul doesn’t remember the words. After the two somethings become overjoyed, he starts to mumble. It is then that the heart swells, and before I know what I am doing, I am shouting at the top of my voice, just the same as all these other lonely people.

TOMORROW DICK IS WEARING PANTS

TOMORROW JANEY’S WEARING A DRESS

FUTURE OUTCASTS

THEY DON’T LAST

TODAY THE PEOPLE DRESS THE WAY THAT THEY PLEASE

THE WAY THEY TRIED TO DO IT THE LAST CENTURIES

And we love each other so, every one of us, because in this moment, we found the cure. Paul may not remember, but we do. We remember every day. It is now that I realize how foolish I have been all along, picking apart the motives of strangers, trying to qualify the “right” reasons to be doing this. I see, in this moment, that their reasons don’t really matter. Paul, Bob, Tommy, Chris, Slim, the other guy, the guy in the bow tie, and the former drummer of A Perfect Circle, ya know, they go through life and they do things and they leave stuff on the ground. We follow in their wake and we pick it up and what happens next is up to us. When I was 16, I decided what was going to happen next, after I picked up what Paul put down. I decided I was going to keep going. I was going to find a home for myself, and if I couldn’t find one, I would make one. The world would feed me poison and I could make it medicine, and I could do for those who came after me what Paul did for me, what Alex Chilton did for him, what Roger McGuinn did for Alex Chilton, and on and on and on and on back to painting on the walls. Two interlocking circles. Never give up hope. If you will dare, I will dare.

How many lives were saved by this thankless work? How many people were talked down from the ledge by a disembodied voice on a little slab of plastic? How many times did Paul Westerberg do what no doctor, no parent, no teacher, no president could do? How was he compensated? He wasn’t. He was shit on and degraded and denigrated by the powers that be, his parents’ generation. Well, all those kids, all those orphans he took under his wing, for no “good reason,” for no bottom line you could point at to justify yr actions, they run the world now, and we have found a way to compensate Paul and Tommy and even the other two for doing what had to be done when no one else was stupid or brave enough. Paul Westerberg is a millionaire now. It still seems a little funny, maybe (“Oh, the guilt”), but maybe, just maybe, the world wants to be a fairer and more loving place.

Let it be.

P.S. They sounded awesome.

xoxo