Jerry Williams, Jr. would rather be writing a song than wasting his time trying to wrangle a dumb-love mistake. “That’s the intention most motherfucking mornings,” he says in a reedy southern accent as he stands in the doorway of his six-bedroom San Fernando Valley bungalow. “Then some shit happens.” “Shit” is a car that he wants back. “Two-seater 370Z, I don’t know — said she’d have it for me this morning.” “She” is a mistake.

Williams, 70, is 5-foot-5-inches tall, with a round belly and trim mustache. On this cloudy California day in early February, he’s wearing a tan leather baseball cap, large eyeglasses, a gray button-down shirt, crisp cargo pants, and perfect white Nikes. “I don’t know how to go about getting that motherfucking car,” he says matter-of-factly, and then chuckles and strolls down the hall toward his office. Williams has a perpetually playful, expectant air about him, as if he’s told the world a joke and isn’t sure if anyone’s heard it. “You with the police?” he teases. “They the only ones ever looking for me.”

We pass a wall adorned with commemorative gold and platinum records: DMX’s Grand Champ, Kid Rock’s Devil Without a Cause, Swamp Dogg’s Total Destruction to Your Mind. I linger on the latter: Released 1970, the placard reads, certified gold 1992. “Took its sweet motherfucking time,” says Williams, whom everyone calls Swamp. The Los Angeles-based Alive Naturalsound label, which released the Black Keys’ debut, is reissuing Total Destruction to Your Mind on March 5. The album has a habit of falling out of print.

Swamp lives alone here in this big, dark, tidy house, though this weekend he’s taking care of his granddaughter’s yapping pooch. A vintage Wurlitzer jukebox sits in his living room, loaded solely with his own productions and compositions. I peek into his home studio and see framed Swamp Dogg album covers forming a funky bunting above the instruments and recording gear: There’s Swamp, riding a white rat (1971’s Rat On), looking out from a crumpled photo sitting on a heap of trash (1973’s Gag a Maggot), wearing a white top hat and tails and dancing on a boardroom table (1981’s I’m Not Selling Out / I’m Buying In!). A backyard pool is visible through his studio windows.

Swamp’s affluence is itself a creative project. His most recent, all-new effort, 2009’s An Awful Christmas and a Lousy New Year, the cover of which shows the singer in shorts, as his covers often do, sold 100 copies according to Nielsen SoundScan. Careful with that number, though — the company doesn’t officially stand by sales totals that can’t be rounded up to 1,000. (Swamp’s biggest-selling album of the SoundScan era, which began in 1991, is a compilation called Excellent Sides of Swamp Dogg, Vol. 2. It sold 3,000 copies.)

See SPIN’s gallery of Swamp Dogg’s 11 wildest album covers.

Alternative revenue streams, self-financing, licensing strategies, distribution models. This is the jargon of the musical economy in the digital era, reflecting the harsh realities bemoaned by befuddled indie and major-label artistes alike. Or as the ever-entrepreneurial Swamp understands it, “A bunch of old shit with new names I been doing forever.”

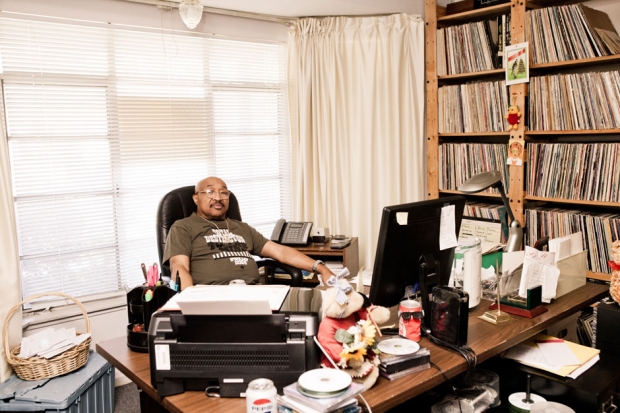

Standing behind his office desk, he puts the phone on speaker and starts to dial. “I can’t even drive stick-shift,” he quips, thinking about the car. “But I still want the motherfucker back.” Based on frequency, “motherfucker” is Swamp’s favorite exclamation, and he pronounces it with impressive variety: MUTHAfucker, muhfuh, motherFUCKER, and myriad other ways impossible to do justice with italics and caps.

One wall of the bright, cluttered office is dominated by shelves holding an eclectic vinyl collection — Funkadelic, Emmylou Harris, The Elephant Man score, all the Swamp Dogg LPs. CD towers holding newer music — Tupac, Faith No More — stand on the floor. On the bookshelf opposite the vinyl are some tools: a rhyming dictionary, unabridged Webster’s dictionary, and a dictionary of synonyms and antonyms. (Swamp has written more than 2,000 songs, and owns the publishing to hundreds more.) A dry-erase board leans against the shelving unit; categories are written at the top of columns: Artist Roster, Friends, Need Songs, Distribution/Licenses, Projects. Each column is filled with names. With the possible exception of retro-soul spitfire Sharon Jones, none would be familiar to the casual music fan. A framed photo of Swamp’s first wife and former business manager, Yvonne, is by the chunky old computer monitor.

An automated voice answers the phone and requests information. Swamp punches in an ID number, then mutters to himself with the puzzling-out tone of someone verbally solving a math problem, “If I can get till Tuesday, then I can wait for…” He hits zero to speak with a loan agent. The phone rings again. “You wanted to observe me. This is what I do,” he says to me in mock apology, “You thought I was a musician or something?”

He is that, of course, and the Swamp Dogg catalog entails one of R&B’s most deliriously idiosyncratic and independent trips. But as a producer, publisher, manager, and impresario of the pop-music margins — with a cottage industry as a cult hero — he’s also a model for how to make a living in the music business in 2013. Well, he’s an idea for a model anyway.

A woman’s voice comes over the speaker: “How can we help you with your loan today?”

“Noooow,” Swamp says, stretching the syllable like taffy, “how do I go about getting an extension?”

Easily, it seems. Extension procured, he’s on to the next task, and dials another number.

“Hey Swamp,” I ask, “did you ever…”

“Twice,” he says, without looking up, “but I don’t fuck with those kind of girls no more.” The phone is ringing on the other end. “I get caught in shit that would make the average motherfucker jump out a window. But it works out. Example: I needed till Tuesday for that loan; they gave me two weeks.”

The phone stops ringing. Voicemail.

“I would really like to have my car back today,” says Swamp. “Now, you promised that I would have it. You texted me at three or four o’clock this morning. I can understand you being tired or something, but let’s just sever all this relationship, and please give me back my motherfucking car.”

He ends the call and sits in the roller chair behind his desk. “All right, you can ask whatever you want,” he says. “You do your job, and I’ll go about my business.”