Los Angeles was the molten-hot core of hip-hip in the early ’90s, and no year was more heated than 1993. The feud between Dr. Dre and Eazy-E had bubbled over, leading to the eye-for-an-eye releases of “Fuck Wit’ Dre Day” and “Real Muthaphukkin G’s.” Dre had already positioned himself as hip-hop’s new don and was on the verge of cementing his power with the impending release of the feverishly anticipated debut album from protégé Snoop Doggy Dogg. Tupac, meanwhile, had proved to be a commercial force over the summer with “I Get Around,” but he continued to clash with the law, getting into a gunfight in Atlanta and arrested for sexual assault in New York City.

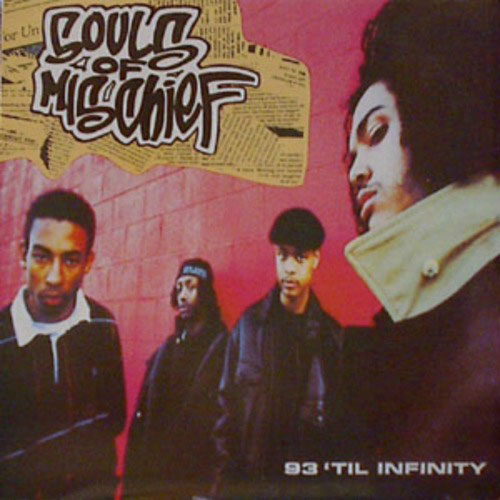

“Sometimes it gets a little hectic out there,” explained Oakland group Souls of Mischief in their 1993 single “93 ‘Til Infinity.” “But right now, yo, we gonna up you on how we chill.” The debut from these four members of the Hieroglyphics crew was defiantly relaxed and laid-back, a cool glass of lemonade in comparison to the gin and juice pouring from the west. Sure, the song fixated on roughly the same things as something like The Chronic — smoking weed, stealing another dude’s girl, talking shit — but the mellow vibes made the few hundred miles between L.A. and the Bay seem a universe away. This feeling was punctuated by the video, which depicts the group in places like Yosemite National Park.

Group members A-Plus and Tajai started rapping together as teenagers under the name Rhythm & Excellence before bringing in Opio and Phesto. Along with Del the Funky Homosapien and a few other Oakland rappers, the foursome then became part of the Hieroglyphics crew. As label interest reached a head in the early ’90s, Rhythm & Excellence became Souls of Mischief. The group went into Hyde Street Studios in 1993 to record their debut for Jive, which soon led to “93 ‘Til Infinity,” a track that had existed in some form since at least 1991. For the beat, producer A-Plus snatched bits of jazz-fusionist Billy Cobham. In speeding up the tempo — the twinkling marimba melody, for instance, is a very slow drip in its original form — he managed to mirror the warp speed with which it means to “chill” as a teenager.

The song was only a modest pop crossover, reaching No. 72 on Billboard’s Hot 100. But by the group’s own admission, the song’s legacy has grown outward since then: You can hear the classic beat used for freestyles by Big K.R.I.T. and J. Cole, two rappers who have also eschewed gangster rap while achieving varying levels of crossover success. Still touring, still recording (much of their last album, 2009’s Montezuma’s Revenge, was produced by Prince Paul), and still hitting young musician’s games like SXSW, the continued presence of Souls of Mischief is illustrative of just how prophetic “93 ‘Til Infinity” was.

Also Read

QUOTE / UNQUOTE

How was the song born?

A-Plus: The original song was called “91 ‘Til Infinity.” We were in high school, just making songs, making demos, trying to get them to send out to people, and it was just a concept for a song. It had a whole different beat. We never really laid the song down, but we wrote verses. Time moved forward and we were working on the album, and we were like, “We should do a “92 ‘Til Infinity.” But the album didn’t come out ’til ’93. So that was that. The other beat was slower, more somber, this was one was more upbeat.

Opio: We were right in the middle of recording the [album], in the studio, doing songs every day. We were fresh out of high school. It was super exciting to be in a big studio. A-Plus would go home and make beats at night.

A-Plus: Back then, we didn’t have any money. People did odd jobs, this and that. So I didn’t have a whole bunch of money to buy records, but I did whenever I could. I found that particular record, it’s a Billy Cobham album called Crosswinds. At that point it wasn’t one of the hot records for people to sample. It didn’t cost hella money, it was in the dollar bin. I just grabbed it, and when I got home, I listened to the sample. I used to listen to my samples on 45, because I didn’t have much sampling time in my sampler. [It was] some cheap shit. [The record is] a little gritty, but listening to it on 45, I was like, “Aw, this’d be dope, I’m gonna make it uptempo.” It was dope, but hip-hop at the time, I was trying to do something faster, a little bit uptempo. I put it together really fast. I didn’t even think it was a big deal, actually, until people were like, “Yo, that’s fucking dope.” It was just another beat.

Pep Love: He came to the studio, and was like, “This track right here is for you. This is hot. I think you’ll kill this track right here.” And he played it at the studio. And a couple members of the Souls were there.

Opio: We were like, “Yo, this beat is crazy.” He was like, “Yeah, well, I gave it to Pep,” and we were like “No, we are pulling rank here, because we’re in the middle of working on an album.” We just kinda bogarted the beat.

A-Plus: Pep’s a good guy, man, he was like, “Aw, for real?” We were recording our first album, and it was just a big opportunity, and I just kinda had to break it to him.

You guys trade bars on the song, which was a bit unusual. What was the reasoning behind that?

Tajai: We did that with a lot of our songs, man.

Phesto: Compositionally, we wanted to include everybody. And it’s kinda hard to do that with everybody kicking a 16-bar verse. You got four 16-bar verses, and hip-hop music is so repetitive, it’s a loop. So in order to keep the ear interested, we were just like, well what if we just trade off, like rapidfire in that sense? And that way everybody gets to have equal time on the track.

Was it crazy for you guys at home once the song became a hit?

Tajai: We were on tour the whole time. We were away from our home when it was blowing up. When we came back it was big, but we were coming off a tour. We could tell during the tour, like after the album came out maybe, who bought the album, because they’d know the words to a lot of our songs. But as far as it being some crazy superstar moment or something like that, man, we’re from Oakland. Nobody cares if you blow up. Hammer could come through and folks would be like, “Yo, Hammer, what’s up?”

Opio: That song in particular, as popular as it is now, and how many people know it, you gotta realize that’s over a long period of time. That song, even though it was really popular, and it really made an impact, and a lot of people really loved it, it never got so popular. Like it wasn’t playing on the radio every day. It wasn’t, just, video on all the time. It wasn’t like that. Over the years, that song has just grown and grown and grown, and touched other younger generations.

Do you remember the first time you ever heard it on the radio or saw it on TV?

Phesto: I remember walking down the street or driving down the street and I would see somebody drive by and I’d hear the song. At that time, you don’t really have a scope of how many people are playing the song. But there was a TV [channel] back then called the Video Jukebox. I used to always watch Video Jukebox because if there was a new video that I wanted to see, I could just call in and request it. I remember watching that show and seeing our video come on back-to-back. And I think just from being in this area, that was a direct indication that people in the area were ordering the video and enjoyed seeing the video. I used to trip off that.

Tajai: Without The Box, I don’t think half of the artists that were on at that time would have broken. It was really at a point where the people could determine what the hell they wanted to watch.

Why did you guys go out to the mountains to shoot the video?

Phesto: People think of California, I don’t know if they realize how many different kinds of microclimates we have out here. There’s beach, there’s snow, there’s mountains, there’s desert. We’ve got a metropolitan, urban, inner-city. That was where that concept came from. And that was the late, great Michael Lucero who directed that video. He came up with the concept, what he saw visually from the audio. When he listened to the song, that’s what he came up with.

A-Plus: Michael Lucero, he was a visionary. He wanted to do something different from everything else that was happening in rap. So when it was our turn to do a video with him, he was just like, “Look, I’m gonna hook you guys up. But I’m gonna do what I wanna do… We’re gonna go to Yosemite, and we’re gonna go to Pinnacles.”

Opio: Northern California is beautiful, and that’s part of what he did. He captured that Northern California vibe. Southern California is warmer. Northern California, the beach is very rugged. It’s very cold, windy. He got the redwoods in there. He got that element that was different from what people think California is.

Phesto: One of the camera guys had this Steadicam on, and he was filming, basically on the edge of this cliff. He slipped and they basically saved his life. They caught him. I just remember being like, “This dude has guts.” Even being on that cliff, it was gravel, so he slipped and somebody else caught him. With this big Steadicam on, you’re like off-balance. Luckily he survived.

Opio: We drove to a bunch of different places, just kinda stopped along the way.

A-Plus: I remember sleeping on top of the RV one of the nights. At least one, we slept on top of the RV in sleeping bags.

Phesto: We were gonna go to Joshua Tree. There were a lot of places we were gonna go that we didn’t make it to.

How do you guys feel about the way the song has continued to grow in stature over the years?

Opio: When people choose to freestyle over that track, I don’t think every single time it’s just the decision of the artist. Sometimes it’s their management. They’re smart enough to know that if you pair your name with this song, it’s such a meaningful thing to so many people.

Tajai: If you tie yourself to that song, you’re tying yourself to the last great — I don’t mean “last” as in “final,” I mean “last” as in “previous” — era of hip-hop. Even if you’re not into it, once you use it, it’s like, “Oh, he’s got good taste in music.” So it’s cool to me because the song used to just represent a year, and now it represents a whole time period.

Phesto: When I think about it, it’s almost like self-prophecy. We said “93 ’til infinity,” and then the song is still here. Now you have people from younger generations who were born in ’93, and they’re like, “93 ’til infinity.” It means so many different things to so many different people.