On April 8, 1994, Kurt Cobain was found dead at his home located just outside of Seattle, Washington. Twenty years later, we’re still processing the loss. To mark this sad anniversary, the editors at SPIN have dug into the archives and collected some of our finest coverage on Cobain and Nirvana. We’ve dusted off early-’90s cover stories that were written when the now-iconic band was new to the Billboard charts; revisited tributes penned in the wake of Cobain’s passing; and rounded up photos of the man, his bandmates, and his family members that have populated our pages over the years. Now, we present SPIN’s original reviews of some of Nirvana’s most beloved recordings, because, after all, it was the music itself that inspired our devotion in the first place.

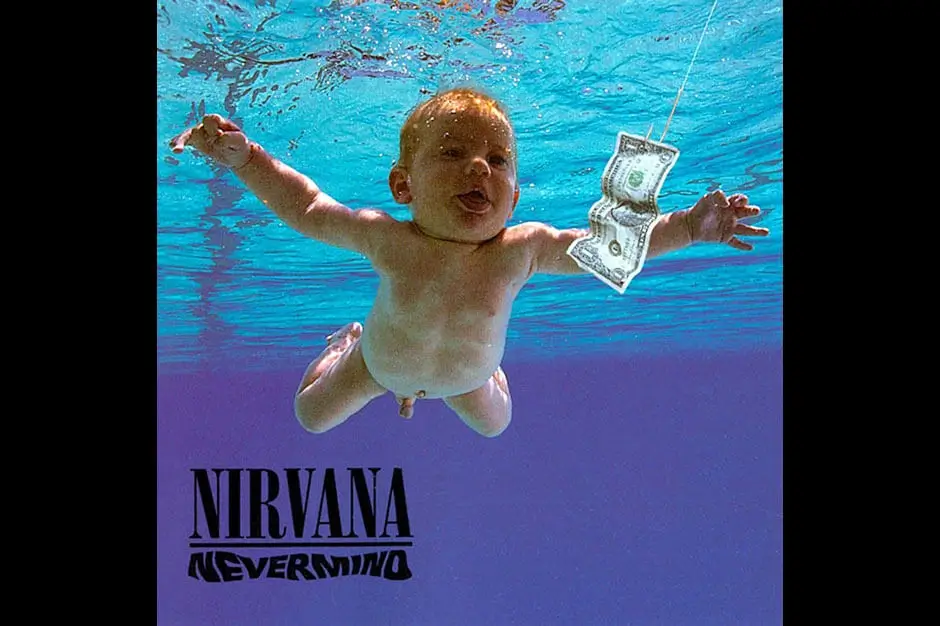

1. Nirvana, Nevermind (DGC), 1991

After a most fine lunch on a bright sunny New York day, Nevermind is blasting through the little box on my desk and the finance department here at the lovely SPIN offices are probably going ballistic… But so what. Forget the new Guns N’ Roses double overkill. Forget Rush’s Roll the Bones. Nirvana has built this one for speed — that would be speed with a capital “S” — and it sure is fun to drive. A little bit punk, a little bit metal, a little bit country, a little bit rock’n’roll. What the hell more do you want?

Nevermind’s got a full-out rock assault on “Territorial Pissings,” and a beautifully harmonic “On a Plain,” and a really cool song called “Breed.” Anyway, I swear you’ll be humming all the songs for the rest of your life — or at least until your CD/tape/album wears out. I’m fully about this record, and you will be too.

Lauren Spencer

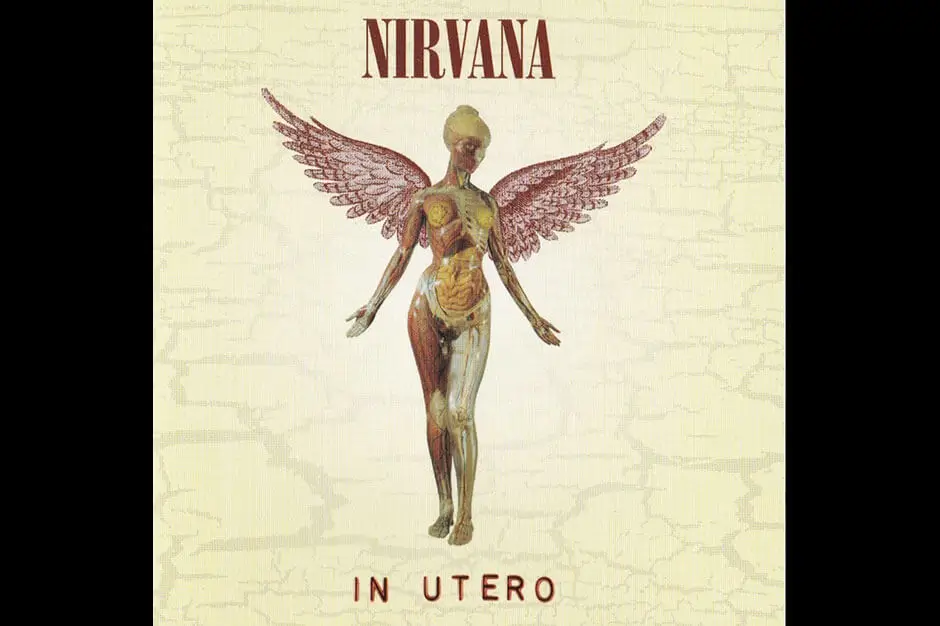

2. Nirvana, In Utero (DGC), 1993

You can almost taste the mixed emotions in Kurt Cobain’s mouth on In Utero, spat out as if the singer were trying to expel his tongue along with the lyrics. The more extreme that voice gets (the screams of “go away” on “Scentless Apprentice,” the wash of babble on “Tourette’s”), the more music rises to the bait: grinning slash-and-yearn feedback that’s half drunken game of chicken, half accident scene postmortem. It’s only been two years since Nirvana suddenly gave punk the face of profit with Nevermind, but from the sound of the new album it could be two decades. Fame has aged Cobain’s plaintive rasp, as if celebrity were some kind of public dungeon that turned his shout into a prisoner’s, looking for an echo in solitary confinement.

The songs of In Utero are fractured, spasmodic, wrenched out of shape — notes pulled inside out, meanings stood on their pointy little heads and spun for kicks. Pushed to the brink, Cobain’s mercurial guitar, Dave Grohl’s self-contained drumming, and Chris Novoselic’s split-the-difference bass have never been as cohesive. The sinister, inexorable momentum of “Serve the Servants” leads straight into the bottomless riffs of “Scentless Apprentice,” a playground dissolving to reveal the mouth of a volcano.

This sound — an inclusive black hole — was taking shape on Bleach and the best leftovers that Incesticide collected, only now the scaled-down contradictions of “School” and “Aneurysm” have been blown up (in every possible sense). “Smells Like Teen Spirit” taught how much revulsion and excitement Nirvana could cram into that four-minute format, but it left the rest of Nevermind looking like stock gestures, flimsy excuses, a failure of nerve. But despite the rumors that had In Utero being rerecorded or otherwise toned down (two tracks are acknowledged as having been remixed), and the subconsciously melodic hooks embedded in the noise, this is as reckless as anything since the early ’70s Cleveland punk prophets Rocket From the Tombs went down in flames.

The album’s starting point is the old stardom-as-martyrdom routine, most vividly announced in the back-to-back “Rape Me” and “Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle.” The former opens with a snatch of these now generic “Teen Spirit” chords, gutting them to hint at media vampirism. “Frances Farmer” is an allusion turned into a slick pun by “Rape Me” — in honor of the hometown actress who was persecuted, institutionalized, and eventually assaulted while undergoing “treatment.” Driven by the music, self-pity is purged and the sense of violation expands, returning as a curse on life itself: “She’ll come back as fire / To burn all the liars / And leave a blanket of ash on the ground.”

Set loose on In Utero, that spirit is able to make all sorts of invisible connections, bringing the ruptures of history to bear on the present. Perhaps that’s how ghostly echoes of “Apokalyptickej Ptak,” recorded by the banned Czech group Plastic People of the Universe in 1975 (and not released until 1992), could have passed through borders of time and place to emerge from the guitar carnage on “Radio Friendly Unit Shifter.” Maintaining this fugitive spirit, it’s not liberation but its absence that gets illuminated in Nirvana’s songs. Instead of barbed wire and secret police, there’s paralysis.

In “Pennyroyal Tea,” as bitter and empathetic a song as Nirvana has attempted, the nominal subject is abortion. The title refers to a homemade recipe for inducing one, but it’s not a song likely to comfort people on either side of that issue. With a nod to the Beatles’ “I’m So Tired” (Lennon is surely Cobain’s deepest source as a singer), it’s about the ugly scars any difficult choice leaves. Officially sanctioned guilt bleeds into private despair, false consciousness merges with real pain. “Pennyroyal Tea” gives us repression and denial as conditions on which nobody has a monopoly. The song’s not a righteous placard of a fetus or a bloody coat hanger, but a desperate, unresolved awakening to how much of ourselves we’re required to kill and maim every day.

Listening to “Pennyroyal Tea” and the rest of the album, I thought of a nearly forgotten punk masterpiece of 15 years ago: Magazine’s hopeless, exhilarating “Shot by Both Sides.” That’s Nirvana’s motto here: surrounded, lost in a hostile crowd, gagged but trying to talk back anyway. With In Utero, I suspect Nirvana intended on some level to summon up the specter of punk in order to give it a proper burial — drive the final nail in the heart-shaped box and leave behind a fitting tombstone. Setting out to make the last punk album, it made what sounds like the first one instead.

Howard Hampton

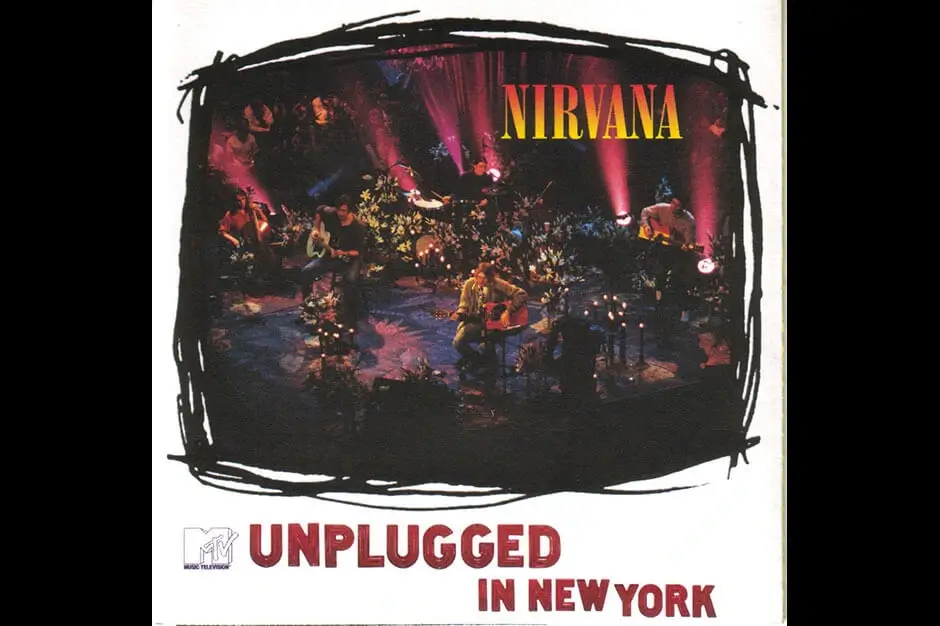

3. Nirvana, MTV Unplugged in New York (DGC), 1994

Like most of us, you may have first encountered the spooky grandeur of Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged performance in April 1994, after Kurt Cobain opted for a death worse than fate. It’s a tribute to Nirvana’s musical power that listening to the resulting CD doesn’t feel much like staring at a train wreck. Instead, it feels more like great rock’n’roll. Cobain’s purist tendencies on Nirvana’s official releases could be grating, often making him sound like an electrified Tracy Chapman, but the acoustic setting of MTV Unplugged lets him explore his folky strengths at an open-throated peak. Buoyed by the one-take intimacy of the format, Cobain sings with a sinewy, rough-hewn timbre of truly Dylanesque proportions.

Cobain’s death forms the inescapable context for Unplugged, giving it an aura of sanctimony that doesn’t do justice to its sonic beauty. His legacy to rock’n’roll was a mixed blessing, especially for those of us who expect music to pay at least lip service to the pleasure principle. In the wake of Nirvana, American rockers cling to their own back-to-Africa movement, an escapist fantasy away from fake music into real music. You know the drill: Rock’n’roll would be so much better if we could just make tapes and give them away at shows, or maybe just hitch from town to town and sing for the kids! This fantasy has done more to bleed the humor and spontaneity out of music than samplers ever did. After all, the blandishments of corporate rock never stopped Boston’s “More Than a Feeling” from sounding like divine intervention, or prevented ZZ Top’s “Rough Boy” and Def Leppard’s “Photograph” from communicating recognizably human emotions. If Poison wrote better songs than Beat Happening — and it did — then there’s something crippling about the purist scam.

So it’s profoundly moving that, with Unplugged, Nirvana creates its loveliest music by capturing the simple pleasure of being a fan. Cobain growls David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World” with empathy and wit, and while Krist Novoselic pumps his accordion like a carnival madman Cobain turns one of the Vaselines’ lesser ditties, “Jesus Don’t Want Me for a Sunbeam,” into a folkie mass in the basement of Our Lady of Perpetual Sorrow. Wailing his way through “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” Cobain takes Leadbelly even further than Van Morrison into a realm of gritty splendor haunted by Lori Goldston’s hair-raising cello.

And when Cobain concludes his dolefully drab “Something in the Way” to pluck the opening notes of the Meat Puppets’ “Plateau,” it’s as if he’d just pulled up the shades to see the dawn. Two of the Meat Puppets, Cris and Curt Kirkwood, show up to strum away as Cobain lovingly imitates Curt’s high-lonesome mewl in “Plateau,” “Oh Me” (omitted, like “Something in the Way,” from the original MTV broadcast), and the harrowing but funny “Lake of Fire.” The Meat Puppets’ casually erotic melodies inspire Cobain to indulge in a joyous escapist fantasy of his own.

Incredibly, this fantasy not only influenced Cobain’s songwriting but nourished its growth. On Unplugged, you can hear a world of difference between the selections from Nevermind and In Utero. Sometime between those two albums, after coming in contact with a broader audience, Cobain wrote the songs that fulfilled the promise of his 1990 single “Sliver.” Anyone who’s ever done time in mental illness can tell you that Nevermind romanticizes its subject with too much sentimental hokum, more Hans Christensen Andersen than Lou Reed. But In Utero‘s adult love songs still sound realer than Real Deal Holyfield. “Heart-Shaped Box” utterly convinces you that Cobain has sunk his teeth into another human heart and will never let go. And on Unplugged, “Dumb,” “Pennyroyal Tea,” and “All Apologies” are the music of a lifetime.

“All Apologies” begins hesitantly, fingers tapping on strings in a brittle staccato, until Dave Grohl’s elegantly brushed drums push Cobain into a terse valentine to a lover who has married him and buried him, a lover from whom he can’t escape because after he’s tasted the joy of being easily amused, it hurts too much to go back to jaded detachment. The melody, as my squeeze pointed out, comes from Glen Campbell’s evergreen “Rhinestone Cowboy,” and so does the mood: There’s been a load of compromisin’ on the road to Kurt’s horizon, but he’s gonna be where the lights are shining on him. Unplugged captures the moment of Nirvana bathing in its own richly deserved light, and though the moment couldn’t last, nothing in the music suggests there was anything inevitable or natural about the next chapter of the story.

Rob Sheffield

4. Nirvana, From the Muddy Banks of Wishka (DGC), 1996

Let all the analysis fall away like yellow, aged newsprint. Crank this record up… — Krist Novoselic, from the liner notes

Let’s take it way, way back. How did you feel the first time you saw Nirvana live? High. / Kinda cheerfully wound-up, as if the crowd might riot. / Horny and full of myself, like I had this big red flower of promise growing in my chest. Okay. This is the story Nirvana’s second live album wants to tell: The rocket arc that ended in dull death began by making people feel life more dearly.

Is it a true story? Depends on who you ask; it’s true for this writer. But another narrative invariably snakes across the current, hissing low about the sure demise of possibility. From the Muddy Banks of Wishkah lives to tell that tale too. And how could it not, really? For Nirvana, the tail of one was food for the other, empathy swallowing disgust, despair eating passion; a fine tension until Cobain broke the circle. All Novoselic and Dave Grohl can finally do, in carefully culling and sequencing tracks, is rewrite the ending so that it smacks less of destiny. Turns out that’s no small gift.

Wishkah (“Wishkah,” by the way, being the river next to where Novoselic and Kurt Cobain grew up) sets the scene with a slice of sound check: Amiable chit-chat, bass runs, a brush of guitar, and five corrosive practice screams. In other words, listen up — that trademark Cobain yowl was a style, not (or not always) a festering wound. Six songs from fall and winter ’91 shows at the Del Mar Fairgrounds and Amsterdam’s Paradiso follow, Cobain playing that voice lusty and self-mocking on “Aneurysm,” trapped and thrashing on the visceral “School.” Still, an incandescent “Lithium” — the album’s first stone essential — wails with such a wide open, feverish panic that it’s easy to see how Cobain’s “raw” feelings launched him into the mythic.

The alarming fervor conveyed by “Lithium” has, of course, as much to do with the musicians as it does the singer. Post-Nevermind, countless bands have attempted Nirvana’s sexual seesaw between soft and hard, tune and power, and not one has managed this physical fluidity, this sensual push and pull, this dance. I won’t lie to you: A few of the rock tropes Nirvana trusted in 1991 sound squirmfully quaint — no one should have to hear another guitar drop portentously out of sight before returning in hideous triumph. But the quickening agent between these three survives, and with it the songs. Even a slurred “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” apparently already suffering from Cobain’s sense of overexposure (and now mine?), strikes fresh sparks off the intro and finishes with stampeding grace.

There’s some horror, then, in tumbling from 1991’s frequent heights to a fall 1993 performance of “Sliver,” startling mostly for the peevish vocal — a clenched-jaw shift in tone away from sympathy to self-protection. The song’s mischievous child’s-eye simplicity just drowns; it can’t hold up adult-size disenchantment. The track is followed by Cobain’s Rome ’91 drugged-Elvis impersonation on “the first Nirvana song ever,” “Spank Thru,” as if to remind us that the singer often messed with his delivery. Yet, the nasal, exaggerated whine of “Sliver” rides again on the next three late ’93-early ’94 recordings, a badge of Cobain’s increasing isolation from his audience — now a roaring hunger in an echoing arena.

The happy difference with these three In Utero numbers is that the band (including guitarist Pat Smear) has since caught up with Cobain, challenging his bitchy screech with unison movements of equally imperious midnight depth. Wishkah doesn’t get any more gorgeous and indispensable than this. Blasted free of Steve Albini’s cloudy crunch, “Scentless Apprentice,” “Heart-Shaped Box,” and “Milk It” writhe as blackened, mad, and voluptuous as a tangle of trapped eels. The music once again balances pleasure and dread, although precariously and mindlessly, like urgent, anonymous sex.

Everyone knows what happened next. Here the narrative of Wishkah suddenly backtracks and splinters, attempting to show that there were many Nirvana stories, and no scripted ends to any of them. Callow 1989 versions of “Polly” and “Breed” with drummer Chad Channing suggest that, but for Grohl and producer Butch Vig, Cobain might’ve gone on making obscurely promising Sub Pop records. The spiritually exhausted man drowning in an October ’91 “Negative Creep” (the ending hidden in the beginning) is offset by the merry demon raging through a torrid ’92 “Tourette’s” with his bandmates, making teeth-bared, hands up, roller-coaster fun.

As a closing argument, Grohl and Novoselic offer “Blew,” a Bleach metal-machine backfire reforged in 1991’s brightly melodic furnace. Cobain’s guitar solo shimmers and shivers like the air above hot asphalt; while the band animal surges beneath his last vows adding exclamation marks. “You could do anything [!] / Could do anything [!!] / Could do anything [!!!].” If MTV Unplugged in New York offers prescient presence-of-the-martyr awe, Wishkah wades fists up into a fitful, eternally undecided struggle (he could’ve done anything). The best of these tracks weigh potential against stasis, finally choosing the former because trying hurts, because feeling nothing would be worse. They make me violently, intimately angry. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Terri Sutton

5. Nirvana, Nirvana (DGC), 2002

Conspiracy theorists must love the new Nirvana single “You Know You’re Right.” If you never bought the notion that “All Apologies” was Kurt Cobain’s oblique suicide note, “You Know You’re Right” — Nirvana’s final recording and the sole new track on their greatest-hits package — must seem like absolute proof that Cobain’s true plan was to retire from the music industry and that the most damning lines of his suicide note were actually scrawled by “the real killer.” The lyrics indicate a fierce hunger for life: “I will never bother you… I will crawl away for good… I will move away from here… You won’t be afraid of fear.” It’s, like, so totally obvious.

Or then again, maybe note. Nothing Kurt Cobain ever howled through his Throat of a Generation was self-evident, which is why Nirvana came to represent everything to everybody. That anticlarity is all over Nirvana. It’s a retrospective that resurrects all the questions Cobain left unanswered when he left us. Are mosquitoes and mulattos (“Smells Like Teen Spirit”) truly connected? Is it wrong to like pretty songs if you like to handle firearms (“In Bloom”)? Is there really no difference between the past, the present, and the theoretical (“Come As You Are”)? Much like the Led Melvin riffage sluicing off Cobain’s left-handed guitar, everything was distorted. Oh, he proved he could write a narrative pop song when he felt like it (“Sliver”), but he felt like proving that only once. The rest of his musical existence was spent inside the soft-loud-softness of his own consciousness (“Lithium”) or behind the singularity of one oddly specific thought (“About a Girl,” “Been a Son”).

It feels a tad weird to be so excited about a collection of ghost songs, many of which have never stopped haunting alt-rock-radio playlists. “You Know You’re Right” aside, we won’t hear any of the supposedly mind-boggling unreleased material Cobain left behind until the box set comes out in 2004. The target audience for Nirvana (released just in time for the holiday shopping season) seems to be kids who’ve read about the band in articles about the Vines, kids who know they’re supposed to respect the hell out of Cobain but don’t really know why. In death, as in life, Cobain remains the man who sold his world, in all its puzzling contradictions. Now that world has been repackaged and sold again, and I’ll buy it, and so will you.

Chuck Klosterman

6. Nirvana, With the Lights Out (DGC), 2004

Listening to this, I can’t help but think of the wisecracking carnival barker in that famous 1960s antiwar song “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin-to-Die Rag”: “You can be the first one on your block / To have your boy come home in a box!” Kurt Cobain has indeed come home in a box, rectangular rather than heart-shaped, after years of legal wrangling between his bandmates and his widow. Sure, the material on the three-CD/one-DVD With the Lights Out — outtakes, B-sides, demos, live cuts, radio performances, and video footage — is mostly great. But this kind of posthumous vault-cleaning is always depressing, especially when it illuminates roads not taken, which this set does. So prepare to be depressed, when you’re not being blown away.

Or cracking up. Disc One recalls how funny Nirvana could be, at least in the early days. It begins with a 1987 live cover of Led Zeppelin’s “Heartbreaker.” Someone yells the title, and Kurt yells back, “I don’t know how to play it” — before ripping through the song almost perfectly, speed-wank breakdown included. It’s not the only Zep cover. There’s also a partial “Moby Dick” and, on the DVD, a startling version of “Immigrant Song,” from a rehearsal-cum-hang videotaped at bassist Krist Novoselic’s mom’s house. It’s amusing to see the self-deprecating punk aping the self-aggrandizing rock gods. But you quickly realize that musically, Cobain’s not kidding. The camera pans, mid-song, to the face of a beer-swilling dude on the sidelines; his slack-jawed amazement is priceless.

At bottom, Nirvana was always a mix of Zeppelin-esque heavitude and arty punk rock. You hear the latter in the early demos here: the Ween-like “Beans,” the strummy indie-pop tune “Clean Up Before She Comes,” and the dubby post-punk of “Don’t Want It All.” There’s also a 1989 trio of Leadbelly covers — the howling acoustic “They Hung Him on a Cross,” a blues-jamming “Grey Goose,” and a rockabilly-ish “Ain’t It a Shame” — that show the band experimenting in ways they never did on their album releases.

Disc Two has acoustic demos both familiar (“Lithium”) and unknown (the brilliant “Opinion”), plus bootleg fodder like “Verse Chorus Verse” that shows the band hitting its creative peak. Things get scary by Disc Three, beginning with two versions of “Rape Me” — a brittle acoustic take and a shredding band demo in which you hear a baby (Frances Bean?) wailing in the background. The DVD ends with a 1993 cover of ’70s pop hit “Seasons in the Sun” — you know, “Good-bye my friends it’s hard to die / When all the birds are singing in the sky” — with Kurt singing and playing drums, intercut with heartbreaking goofy home-movie footage. Like the Zep covers, it’s the sound of a guy who penned his own script, playing it for all he’s worth.

Will Hermes

7. Nirvana, Live at Reading (DGC), 2009

Nirvana’s headlining gig at the 1992 Reading Festival looms infamously large because of (a) that amazingly creepy photo of Kurt getting wheeled onto the stage looking like Norman Bates’ mother, and (b) the show was a mind-blower — sloppy indie rock as stadium-filling psychedelic punk. Most of Nevermind and a fair portion of Bleach are here, as are fetal versions of “All Apologies” and “Dumb,” and a cover of über-influences the Wipers’ “D-7.” As one might imagine, Kurt sounds alternately world-destroying and already dead.

Joe Gross