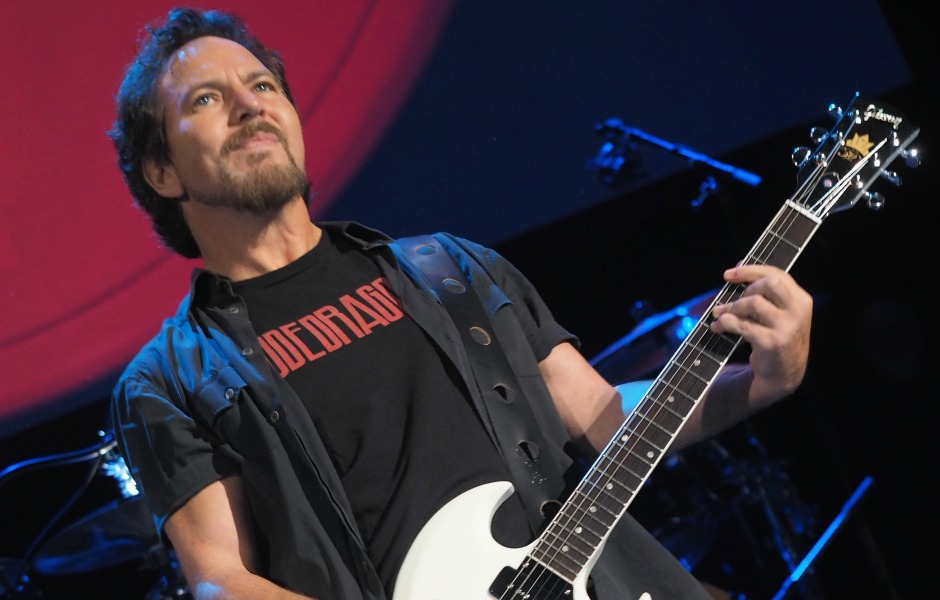

“I know I was born, and I know I’ll die / the in-between is mine,” Eddie Vedder sings on Riot Act, Pearl Jam’s recently released seventh album. From his earliest days, Vedder’s in-between has been filled with music, from the dynamic voice of the young Michael Jackson to the world-weary growl of the eternally old Tom Waits. Somehow, Vedder’s lifelong passion for music has landed him in the position he’s in today: sitting on the terrace of a New York City hotel’s penthouse suite on a windy fall day, chain-smoking and sketching the arc of his life through the records that have moved him the most.

Holding his head in his hands, he looks skeptically at a list he’s spent a week preparing, filling the pages of a black composition book. “I have some hesitation about this, because it might demystify everything,” he says. “Our influences are who we are. It’s rare that anything is an absolutely pure vision; even Daniel Johnston sounds like the Beatles. And that’s the problem with the bands I’m always asked about, the ones derivative of the early Seattle sound. They don’t dilute their influences enough.”

Vedder doesn’t sound bitter, but it’s clear from his list that he’s got a soft spot for artists who carve out their own niche with little regard for trends or fashion, from nerd-core pioneer David Byrne to indie experimentalist Jim O’Rourke. Perseverance is a theme that pops up repeatedly on Riot. “Love Boat Captain” is by turns elegiac and propulsive as it mourns the people trampled to death during a Pearl Jam set at a Danish rock festival in 2000 (“nine friends we’ll never know”). The song concludes with Vedder telling himself that all we need is love, a classic rock sentiment that universalizes the tragedy. Like the musicians he reveres, Vedder is willing to take on tough issues. He saves his scorn for those who don’t try at all, particularly our commander in chief: “Born on third, thinks he’s got a triple,” he snarls on “Bushleaguer.”

To understand Vedder is to understand his favorite music. Taking pains to point out that his bandmates’ lists would need to be factored in for any true summation of Pearl Jam, he turns back to his own. “If you were somehow able to melt all these records together,” he says, “it would be exactly our music.”

Jackson 5, Third Album (Motown, 1970)

“This is the first real memory I have of any music that stayed with me. I was living on the wrong side of the tracks in Evanston, Illinois, in a home for boys. We had these Jackson 5 records. I really related to their voices–they were about my age, but they weredoing it. It was like, ‘Get up girl, sit down. I’ll show you what I can do!’ And you would do it. Whatever you say, Michael.”

The Beatles “The White Album” (Apple, 1968)

“This is almost a textbook for someone born in 1964. I had a tape that was called ‘Revolver White Album.’ I didn’t find out they were two separate albums until years later. ‘The White Album’ has songs that appeal to little kids, like ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,’ Then, if you get into it, you’re listening to ‘Revolution 9.’ I mean, that stuff opens you up. It’s where you first get comfortable with ‘difficult listening.”

The Who, Tommy (MCA, 1969)

“I think a babysitter brought over Tommy. And I’m already into ‘The White Album,’ so I’m used to, like, two hours of music. I was moved by the theatricality of Tommy. It had an overture, a theme. I got really into listening to it as a linear piece. It went beyond the three-minute song. When you hear these things early on, it changes how you feel about music; you start accepting things that are different.”

Ramones, Road To Ruin (Sire, 1978)

“I was never really that cognizant of punk rock–I didn’t have my first Mohawk until I was 22–but this one kind of cracked the egg. It was somehow frightening, maybe because of the way they looked like a gang. When I was 13, I got my first guitar, and I could sort of play Ted Nugent songs, but I couldn’t play the solos. But I could play along with entire Ramones songs.”

Talking Heads, More Songs About Buildings and Food (Warner Bros., 1978)

“After the Ramones, it was more about new wave for me than punk. I forget which album it’s on, but there’s a song with the lyrics ‘Be a little more selfish.’ My parents were splitting up around this time, and I was thinking how everyone else’s family is going well and mine was splitting up. That line really hit me and got me out of that way of thinking.”

Various Artists, Music and Rhythm (PVC, 1982)

“Peter Gabriel put this world-music compilation out. I got it simply because there was a Pete Townshend song called ‘Ascension Two’ on it, this bizarre jam. The album also had the Drummers From Burundi, a Balinese monkey chant, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. It just opened up my musical landscape. Years later, I actually got to play in a band with Nusrat for a couple of days, and it was incredible.”

Sonic Youth, Daydream Nation (Enigma, 1988)

“I’m sure there’s a couple records I’m leaving out before this one, like R.E.M.’s Murmur or Chronic Town. Those were the years when I was smoking pot, so there might be a few things lost to memory. But I definitely remember hearing ‘Teen Age Riot’ [the first song on Daydream Nation], and I was just in. Steve Shelley’s drumming had this momentum to it, and their approach to guitar–the way they created waves of sound and rhythm–I had never really heard that before. And the lyrics on the album felt like an adventure. I could relate to some stuff, but I also felt like I was looking in on something I hadn’t experienced yet. Same with the Ramones. To me, that’s what New York feels like. I was very intimidated by New York, and I still am.”

Jim O’Rourke, Insignificance (Drag City, 2001)

“The first song is almost like a chant, with beautiful melody and arrangements, and Jim singing about how people of the world need to take over, ’cause if we don’t the world will come to an end. I’m probably biased, since I know Jim, but he’s one of those guys who, if you listen to his records–it’s like if you have a friend who’s an artist, who you know pretty well, and then you see one of his paintings and you think, ‘Jesus Christ, there’s a lot more going on with him than I thought.’ That’s kind of like Jim’s records.”

Fugazi, 13 Songs (Dischord, 1989)

“I know I saw Fugazi live before I heard this record. It was at the Capitol Theater in Olympia, Washington. I think it was one of the early International Pop Underground festivals. I went to the show because L7 were opening, and I was friends with them. Fugazi were transcendent. The next day, I got their record.”

Soundgarden, Screaming Life/FOPP (Sub Pop, 1987)

Mudhoney, Mudhoney (Sub Pop EP, 1989)

“Sub Pop was the first label where I knew I could buy the bands’ records and they’d be cool. The band I was in at the time in San Diego actually opened for Mudhoney and the Lemonheads. Little did I know I’d have anything to do with Seattle.”

Tom Waits, Nighthawks at the Diner (Elektra/Asylum, 1975)

“I like the fact that you can’t really categorize this music. I want to come up with a Tom Waits-ish line about Tom Waits: ‘Tom Waits for no man.’ [Laughs] I think he once said that he prides himself on making good background music. But if you try to dissect it or even play along with the stuff, you realize it’s got all these chord changes that are never played straight. They sound like they’re morphing, and the result sounds like an old car that needs a tune-up. You end up with all these sounds that create rhythm, and it’s the perfect bed for a voice.”

Pixies, Surfer Rosa (4AD, 1988)

“The Pixies were huge for me. Frank Black, or Black Francis, as he was called at the time, had this voice–he just let it loose. He’d let it rip, and weird shit would happen. It seemed not so much rebellious, but just free in the way he could just make sounds like ‘aie! aie! aie!’ and still get his point across. He was liberating himself with his voice. David Byrne was the same way. I’ve never really been able to do that. Well, I think I have sometimes, but not like that.”