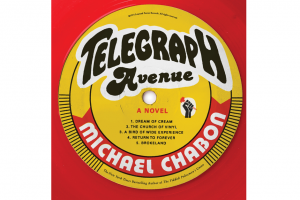

Michael Chabon’s new novel, Telegraph Avenue sprawls, struts, and strolls to the sound of its own funky, jazzy soundtrack. The freewheeling novel tells the story of Archy Stallings and Nat Jaffe, two friends — the former black, the latter white — who run a struggling used vinyl record store on the titular East Bay thoroughfare that divides Berkeley and Oakland. Chabon, whose 2001 novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, deftly sprinkles riffs on soul-jazz, fusion, and rap throughout a story that, at its big-hearted core, is about community, family, and love.

Chabon, 49, who splits his time with his wife and children between Berkeley and Maine, spoke with us about the sounds that inspired Telegraph Avenue over breakfast at a bistro near the Manhattan hotel where he was staying while in town for press. “Especially with this novel,” he said, “talking about music is easy and fun. It’s the other stuff that’s hard. I love to geek out about old records.”

He wasn’t kidding.

First off: Are you a vinyl guy?

I have a lot of vinyl. A lot. I bought my first LP with my own money at age — well, whenever A Night At the Opera by Queen came out, so that was like ’74? ’75. And I kept buying well into the mid-’80s. I had boxes and boxes and boxes. And then I stored it all in my father’s garage to travel. I ended up in California, and I sent for my things, and one box of vinyl out of 13 came back. So I called my dad and I’m like, “Where is everything?” and he’s like, “That’s all there was.” It’s a mystery. It’s like Judge Crater; it’s never been solved. It was one box of records. I have no idea what happened to the others.

Oh my God. My heart would be broken if I lost my albums.

Yeah. It was painful. I didn’t start listening to vinyl again until I was working on this book. It was this cool conjunction of things: I started working on this book seriously and I was walking — running — down the street in Berkeley, and I ran past this house with a dual turntable, the same model as the one I used to have. It was being thrown away! So I go back there and I’m poking around and the guy in the house is like, “You can have that if you want. I don’ t know what to do with it.” So I ran home with this turntable and had it restored at this place in Berkeley that restores turntables. That sort of started me again. I started buying more records.

What have you bought lately?

I’m looking forward to the Sword. Love the Sword — Apocryphon is the new album. It’s coming soon. I’m going to get that one. I also bought the soundtrack to Red Dead Redemption, the game. It’s very Sergio Leono-esque. It’s like elements of Calexico; elements of a Southwestern band. It’s on red vinyl. It’s really good.

Is the appeal of vinyl for you a tactile thing? Or do you think it actually sounds better? I basically think the difference in sound quality between CDs, MP3s, and vinyl is only really noticeable if you’re using ultra high-end stereo equipment.

Three things: I do think the sound is better, especially when you play it on a really good turntable with great speakers and an amp and all those things. I have a high-resolution digital version of Close to the Edge by Yes and I have a really nice copy on vinyl. And it sounds really good digitally — like some things are more defined, maybe, in the sound — but there’s just this power and this warmth [with vinyl]. It’s obvious. I’ve gotten my son and been like, “Listen, there’s no comparison.” The sound quality difference is just apparent. At least it is to me.

What are the other two things?

There’s not just the nostalgia in it, but I like the album sleeves. I like the big photos when you get those CTI records. I never read the excerpts that come with some digital downloads. Why would you? It’s not fun. There’s no pleasure in it. And the third reason is that I have repetitive stress issues in my wrists and I play records when I work and it makes me get up every 20 minutes to change the record or put a new record on. That’s the third reason I do it — not just for my wrists, but for getting up and circulating. It’s not good to sit for long periods of time and all that stuff.

I read that you listen to Yes while writing. It seems insane that someone could do something other than listen to prog rock while they were listening to prog rock.

Yes are one of the few pieces of music that have vocals in English that I can listen to while working. I think it’s partly because the lyrics don’t really make a lot of sense. And plus I’ve heard the songs so many times I don’t really listen anymore. But: Close to the Edge and Tales From Topographic Oceans, Relayer. I listen to those a lot while working. And then another one that’s always fine is The Verve’s first album, A Storm In Heaven. Not their second album. There’s something about the lyrics on A Storm In Heaven, they’re somehow buried in the mix in a way that they don’t get into my head.

The book is full of references to soul-jazz from the ’70s, even down to including discographical information in the text. Were you familiar with stuff like Johnny Hammond and Freddie Hubbard already? Or did you have to educate yourself? And if so, what got you excited about the genre?

It was a cool thing. Everything became important in this book; a lot of things came up by chance. It happens a lot, like if I hadn’t been in a certain place at a certain time I never would have encountered this and I don’t even know where the book would have been. So for my last book, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, or maybe it was Manhood for Amateurs, I was in Raleigh-Durham. I did an event downtown and then they took me out to this bookstore in the suburbs. A very white suburb and this shopping center had this nice, independent bookstore. And I was walking through the store, I was going to the back room to sign stuff, and I saw it had a really good magazine section, like any bookstore, with quirky titles. And I look up and Michael Jackson is looking out at me from the cover of a magazine. It’s like a 10, 12-year-old Michael Jackson just looking so sweet. He had died within the past couple of months, so I hadn’t really sorted through my whole complicated feelings about Michael Jackson and his death.

What did seeing him mean to you in that moment?

I loved Michael so much, I loved the Jackson 5 so much. I remember cutting out the 45 of Goin’ Back to Indiana from the back of a cereal box. I remember cutting it out and putting it on my record player. I remembered all that from looking at the picture and I was like, “What is this magazine?” It was Wax Poetics. I picked it up and thought, “This looks completely awesome.” So I read it and then I went online and ordered back issues from the website and then I became kind of obsessed with it and got every issue up to that point. And in reading all this, this whole world of soul-jazz and jazz-funk that had been the source of so many samples of hip-hop DJs had been using, I was like, “What is this shit? CTI Records and Kudu Records?” It just felt right. And then I really got into the music and I started with this collection called Blue Break Beats — all the stuff that’s been sampled. That was my first introduction, was through those collections. And then I started checking them all out.

I got into the first two Deodato albums on CTI. I loved those. And then Johnny “Hammond” Smith’s Wild Horses Rock Steady, Idris Muhammad’s Power of Soul. There’s this one: Grover Washington Jr.’s Soul Box. It’s this two-disc set. It’s amazing. It has a whole side-length version of Marvin Gaye’s “Trouble Man” that is just so good. He was amazing.

In a lot of sections in the book, the cadences of your sentences have a kind of vintage, funky ’70s blaxploitation vibe to them. Was that influenced at all by the music? Was it difficult to modulate your writing so that adopting that kind of style felt natural?

Not really. The sentences just come cadence first, before I even have any content for the sentence. It’s like an instantaneous process that’s measured in nanoseconds. I feel a rhythm of the sentence first, like three clauses and the third clause is going to be just two words long, undercutting what I said in the clause immediately preceding it. But it’s just intuition, it’s a feeling. And then, nanoseconds later, the words themselves just fill it in. It’s like I made a little indentation in the sand for water to seep into and it’s done. And I just walk away from that sentence and never touch it again.

Obviously the novel’s subject matter dictated this, but did you have any apprehension about writing in a voice that was meant to signify as “black”?

I was very careful. Careful, alert, and I tried to be very sensitive. I also solicited the opinion of other people in some cases. You know, was I laying it on too thick? I trusted myself and I trusted the reader to understand my intentions. But still, there was a really generous review in The Guardian by Attica Locke, and she gave me props for the dialogue and said there were times when she forgot I had written it and it could have been written by Percival Everett or Colson Whitehead. That made me really relieved.

Something that Telegraph Avenue deals with is the shift from brick-and-mortar record stores to online retailing. What do you see as being lost in that change?

It seems obvious to me that being with people physically and talking to them is a different thing than being with them virtually and talking to them in cyberspace, but whether that’s a better or worse thing, I have no idea. It’s completely different. I don’t think, when it comes to things like information, the Internet is a bastion of culture. The Internet has its own culture, which is invaluable, but I don’t think it can, nor should it stop a physical coming-together.

What happens in that physical coming-together?

You buy your music from iTunes and Spotify and you’re streaming it — that has nothing to do with going into a record store and you asking, “Do you have this?” and the guy goes, “No, but have you checked this out?” And he tells you that band is playing at this location two weeks from now and someone else comes over and you get in a good discussion about it and find out about someone you didn’t know about beforehand. You feel initiated into kind of a tribe. But there are things like Listservs or message boards in which people do form lasting relationships about music. It’s like how you get something from live recordings that you can’t get from listening to records and you get something from records that you can’t get from live performances. One didn’t supplant the other.

You’ve written about your love of Big Star. Was finding that band also the result of some serendipity?

Yeah, that’s another one of those weird little conjunctions of things. I always loved Pete Frame’s Rock Family Trees. I have all those books. I read them still, all the time, just for fun. At one point I saw a promotional poster from RykoDisc for the release of a Big Star live performance from a radio station in Long Island that had been bootlegged for years. That promotional poster wasn’t really on a family tree but it placed Big Star in context as a Memphis band that spawned a little bit of its own family tree and then it had all those sort of followers like Matthew Sweet and REM, and the dB’s. And suddenly “Alex Chilton” was a song on a Replacements album and now I knew who Alex Chilton was. I’d loved that song but I couldn’t just Google it to find out who the hell they were talking about. I had no idea. But that poster, which caught my eye because I loved Pete Frame’s work, just hit me instantly, and I bought that CD, which is interesting: The best song they ever did, “September Gurls,” the channel falls out, so it was fucked up. And I was like, “I need to hear this song in its full glory.” Eventually, I tracked down an import, a German import CD with both #1 Record and Radio City on it, and I heard the song for real. I love power pop, it’s one of my single favorite genres of music. I love the Raspberries and Badfinger and Built to Spill, and this whole, incredible body of work that had just been hiding on me. There’s always this element of tragedy. A lot of power pop is about suicides and tragic deaths. The songwriter for Gin Blossoms killed himself and Brian Wilson suffered from depression. With Big Star, you have Chris Bell’s death. It just fit. It all fit.

Another one of the book’s motifs is how music can function as a wedge between generations. The character of Jules confuses his jazz-loving father by listening to prog rock. Growing up, did you use music to set yourself apart from your parents in any fashion?

I accepted all my parent’s music. I never thought, “I can’t like this, because my parents like it.” From classical to jazz to Broadway show tunes, I’d play those records when I was with them and play them when I wasn’t with them. It would’ve been hard — when I got into The Clash, for example, in high school, my mom liked it. When London Calling came out, that song “Spanish Bombs” was one of my mom’s favorites. But it’s not like listening to Pere Ubu, you know, [“Spanish Bombs” is] kind of poppy. But still, whether my parents liked it or didn’t like it wasn’t that important to me.

Is the musical relationship you had with your parents repeating itself with your children?

I’m very musically accepting. I mean, I love hip-hop and I know a lot of parents who don’t love hip-hop and their kids do. But that’s not an issue for me. My son listens to a lot of stuff. Adele. He’s into that. The fact that he’s from Oakland means a lot to my son. He likes to listen to stuff like Wu-Tang. But it would be very hard to find music that I wouldn’t be able to take. Some shitty electronic stuff, probably, I can’t think of any examples. Initially the xx left me cold, but I like the new album a lot. My kids, they introduced me to that. They introduced me to the National. It’s great.

There must be something they play that you’re at least tired of hearing, no?

My daughter, who’s 11, likes to listen to pop. Carly Rae Jepsen. I’ll listen to it because I’m curious and I like pop. But having heard “Call Me Maybe” 415 times I really don’t ever need to hear it again.