She’s lying flat on her tummy on the carpeted floor of a wood-paneled TV room, legs scissoring playfully, elbows propped up, notebooks and legal pads full of scribbling scattered all around. Sports drones from the 20-inch set, but her hands are clapped tight over a Walkman’s headphones, guitars blaring audibly. It’s the reverie of an American girl, raised on rock’s broken promises and suburbia’s lame spoils, and Kim Deal has wallowed in it more than most.

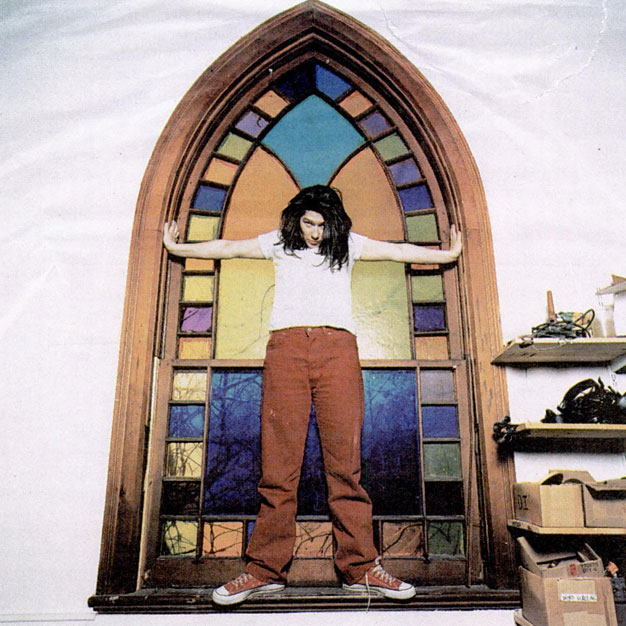

Like one of her teen fans listening intently to the oblique lyrics on the Breeders’ 1993 platinum album, Last Splash, Deal is still trying to figure out what the hell she’s trying to say. The Walkman’s blare comes from basement demos for her first solo album—songs written while the Breeders were on vacation after almost two years of touring—which she’s rerecording and mixing here at Dreamland, a spacious studio in a renovated church in upstate New York. Engineer John Agnello, twin sister-Breeders guitarist Kelley Deal, and Breeders drummer Jim Macpherson are hanging out and pitching in, but this is clearly a one-woman show.

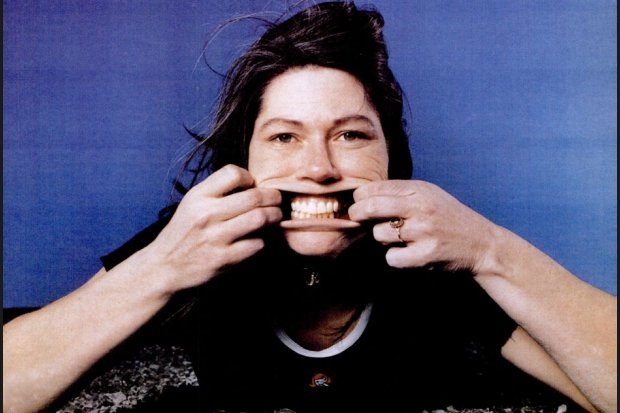

And even though I’m flopped as innocuously as possible on the sofa behind her—we agreed that I could watch the NCAA Final Four if she could run down my Walkman’s batteries—Kim is distracted, her mind flitting back to an earlier conversation we had about the artwork for this article. Notoriously not photogenic, vigilantly democratic and group-oriented, she’s stressed about facing a photographer alone. She’s also painfully aware of the fact that she’d probably move more units if she spruced up her image. “Of course, I know how my photos look,” she says, hopping up, taking a seat on the arm of the sofa. “I know I come off lookin’ like a fuckin’ haggy housewife compared to all these other women in rock, and that’s fine with me, man. So I don’t wanna wash my hair, fuck you, this is how I look.” She cringes, sticks a finger down her throat, and turns up the sarcasm. “Of course, I want to help you out and be nice. You need a good cover, I know that. You don’t care about me, I know that. You just need me to look good for the cover so you can sell magazines.”

Of course, she’s winding me up, but before I can squeak out a protest, she’s off the sofa and on the floor, talking back to the screen. When Bryant Reeves, Oklahoma State’s crewcut, leatherface center, argues a referee’s call, Kim hoots: “Hey buddy, stop whining and play the game!” This is the Kim Deal I’ve come to expect: the no-patience-for-whiners Ohio tomboy, the chain-smoking ex-jock-and-cheerleader who charms you with the size of the chip on her shoulder. But as I’ve discovered over time, if you get past that chip, you’ll find all sorts of other personas—the suburban middle-class daughter who needs her parents but gets queasy when she imagines herself in their sensible shoes; the jaded, vulnerable 33-year-old survivor of divorce; the protective sister who worries herself batty.

It was all of those faces that made Last Splash sound so true-blue. Here was the rare album that had all the l-need-you and you-gross-me-out emotions seamlessly bound together. The songs were slick and gorgeous one instant, sticky and hideous the next, always implying that comfort was a curse we’d crave forever. This was the nub of Last Splash, how suburban family values, as the novelist Michael Cunningham puts it, are “sort of romantic and compelling and utterly threatening—the idea of a safe, predictable life, where every day is prosperous and happy, and every day sort of matches every other day…it’s venom, deadly poison.” Kim Deal would probably give him a pound on that one.

Why do we keep looking for reassurance in places that paralyze us? Later, when I mention to Kim that as a kid I desperately watched sports on TV with my dad so we’d have something to talk about, and that now, ironically, watching sports on TV is one of the few things I find comforting, she immediately perks up. “I know exactly what you mean. When I was in Lincoln Tower [the freshman dorm at Ohio State, one of seven colleges Kim attended but never graduated from], I used to go in the TV room every afternoon and watch General Hospital just so I’d have something to talk about with the other girls in the hall. And I guess I mentioned to my mom one day that I was watching it, because then she started watching it so she’d have something to talk to me about.” Kim pauses, takes a deep drag on her cigarette and flashes the most guileless of smiles. “That’s kind of sweet, isn’t it?—in a pathetic sort of way.”

Kind of sweet, kind of pathetic. That’s how Deal has viewed her life following Last Splash‘s surprising success, propelled by the Top 40 single “Cannonball,” one of the most unlikely mosh notes ever penned. What was meant to be a well-deserved rest for the band after opening Nirvana’s last national tour, headlining gigs with Luscious Jackson, and joining Lollapalooza during the summer of ’94, became a boring winter exile for Kim in her childhood home of Huber Heights, the planned community outside Dayton that thrived in the ’50s with the opening of Wright Patterson Air Force Base, where Kim’s dad worked as a physicist. Instead of catching up on laundry and bad TV, she learned to play drums, patched together a batch of songs, and agreed to help produce the next album by her drinking buddies Guided By Voices (of which her fiance and SPIN Senior Contributing Writer Jim Greer is now a member).

Meanwhile, the other Breeders were plenty busy. Jim Macpherson finally spent some time with his kids and renovated a new house. Bassist Josephine Wiggs fell in love (with Luscious Jackson drummer Kate Schellenbach) and out of the closet (courtesy of a November ’94 Advocate story titled “Luscious Lesbians”), eventually moving from London to New York to be near Schellenbach. Kelley Deal made the most publicized move, out of Kim’s place and into a nearby house where she was arrested in November for receiving an Emery Worldwide package containing heroin. Her trial is set for July. Considering the circumstances, Kim’s desire to record a solo album made more than a little sense, for everybody concerned.

It also made sense to finish up at Dreamland, an unpretentiously cushy scene with its TV room, video game parlor (Ms. PacMan, Millipede), well-stocked kitchen, and four-bedroom crash pad just a few miles away, near Woodstock. There’s lots of room for boyfriends or stragglers, and on that Final Four night, Kim and friends were up past 5:00 a.m. poring over tracks assembled from previous sessions—Easley Recording in Memphis, Steve Albini’s house in Chicago, Pie Studios on Long Island, as well as Dreamland. By mid-afternoon the next day, Kim was bopping around in a blue cardigan and army pants, fresh-faced and psyched, and with good reason. From the sound of the new album, titled Pacer (not after the ’70s hatchback), she may have written some of her most accessible distorted-pop tunes yet. Musically less skewed and angular than the Breeders, the songs’ lyrics are more sentimental, sarcastic, and in-your-face. More like Kim’s everyday personality. She’s still troubled by the same stuff—like always ending up on the shady side of a sunny street—but she seems more anxious to find out what it all means.

SPIN: So is this album a sign that you’re getting tired of maintaining the band’s dynamic?

Kim Deal: Okay, I wanna make this clear. I’m not doing a solo album because Kelley or Jo or Jim were being uncooperative or irresponsible. It was because I work more and faster than they do and I was downstairs with my four-track. The vocals were cranked, more emphasis on the lyrics, so you don’t need a full, working band to play them. Josephine would be going “bum-bum-bum-bum,” it would be boring for her. Plus, I liked the idea of being a total asshole and playing all the instruments. Kelley went around calling me the Artist Formerly Known as Kim….Anyway, the Breeders aren’t really a signed band. I’m signed to 4AD, but just me, not the Breeders. I can deliver a Kim Deal tuba record if I want. When I decide to do another Breeders album, we’ll do it.

But what was pushing you into the basement to start working?

A lot of the songs are just about living in Dayton since September, and the winter was so awful and Kelley was going through all that crap and I told Guided By Voices I’d help ’em and they’d come over at 10:30 in the morning and I’ve got the most wicked hangover….I mean, we were there a long-ass time and it was nice the first couple of months, you know, I love my family, but please, there was Thanksgiving, birthdays, Christmas, the baby [Rebecca Ann, her brother Kevin’s daughter], Kelley, and I just drank the whole time. I swear it’s like every song is about drinking and it’s bad, really, it’s like a Pogues album—”Empty Glasses,” “Tipp City,” “Mom’s Drunk,” duh. Then there’s a line in “Hoverin'” that goes, “Yeah we’re straight / We get high on our music.” It seems like everything has a reference. I hope people don’t focus on all that. (“Don’t worry, they won’t,” adds Macpherson, winking as he takes a seat across from the two sofas where Kim and I are ensconced with Mountain Dews and peanut butter sandwiches.”They’re just gonna keep saying, ‘Oh, here come Kim Deal and the Breeders, those good Christian rockers.'”)

You didn’t leave Dayton all winter?

Well, when I did leave, it was just to go to Guided By Voices shows and that was frustrating too, seeing them. They’re a band, they’re playing together, they’re having shows, because everybody lives in Dayton. We’re like, the bass player lives in England, Kelley may go to jail…

Did anything good happen?

It’s weird, but as the spring is breaking, I’m actually longing for that time in the basement when it was really shitty. Isn’t that weird? I guess there was something good about it. I learned how to play drums, I got these songs, I came up with a name for myself. I’m going to be called Tammy and the Amps, because I’m Tammy and I’m just playing with a bunch of amps.

Why are you Tammy?

Because my lighter said so?

In high school, we used to call the stoner-rock girls with feathered, angel-wing hair “Tammys.”

Yep, you got it.

One of the best things I read about Last Splash said that the album seemed to question whether women could ever really trust rock, since it’s so structured by and for men.

I don’t think it’s not trusting rock, it’s having to trust in the ideal of men in general. You know, you just think you’re going to get married and there’s a future in a person and all that. And there ain’t. Most of the time, guys are weak and cowardly and you come to expect it. Relationships go cold, they do, and that’s sad, and it gets depressing and mean and—

So why are you engaged to Jim?

He asked me and I said okay. So? Yeah, we’ve been engaged for awhile, for marriage, which sucks, which he knows, since he’s done it before, too. We sit around and he’ll say, “Do you want to get married?” and I’ll say, “Why would I want to marry you?” I’d say we’re terminally engaged.

Do you look at motherhood, like marriage, as a shackle? You were the one who sang, “Motherhood means mental freeze,” after all.

No, I never thought being a mom was a shackle. I thought having to be married to some asshole to be a mother just because of the traditional laws of behavior from the fucking 12th century or some fucking papal bull that declared some bullshit rule all of a sudden, that’s what I thought was a shackle. Just because marriage exists doesn’t mean there’s any point to it. It’s made up and stupid and that’s just the sad truth. Babies, you don’t make them up. It’s like when you grow up and find out that your dad’s not the smartest, strongest person in the whole world, or that you recognize faults in your family. It’s sad, but it’s true. I knew this guy who got in a fight with his dad when he was 16 and he knew he could beat the shit out of his dad, and that hurt him more than actually getting into the fight. He knew he could beat up his dad, and that really made him sad.

But you still want to trust in the future of something besides yourself, whether it’s a different person or a different band or whatever. Is it self-negating, then, for women to trust in rock?

I know what you mean, but I don’t think rock exists outside everything and is there to save you. I think rock is more within and you have to bring it out of yourself. The music is within and the love for it is from within, not without. Plus, I think it’s a tad insulting to say that the only thing women can do with rock is to imitate or mock men.

I’m not really saying that, but a lot of women feel distanced from rock stars, like they’re representing or speaking only for guys.

When Jimmy Page was rocking, I didn’t think he was rocking for guys. But there were definitely some bands I felt that way about, where I wasn’t invited to rock along with them. Like the white T-shirt, hardcore punk white guys. They were way meaner than the heavy metal bands and way meaner than some huge Harley Davidson guy with a beard who liked blues. When me and Kelley would get together and play these country songs at bars and truckstops, those big Harley Davidson guys would cry, man, it would move them. Whereas those white T-shirt hardcore boys were very hung up about what girls could do, in bands or otherwise….Now you’ve got guys like Ian MacKaye “saving” girls from the mosh pit. Hey man, fuck you. Girls know what they’re doing when they get in the pit. They don’t need you to save them.

Did you admire any female rockers growing up?

Back when I was a kid I didn’t like chicks in rock, they sucked. The only ones were, like, Pat fucking Benatar and Heart. But I did see Talking Heads in 1979 and I couldn’t believe that that chick [bassist Tina Weymouth] was dressed up like a boy but she looked like a girl. That was really cool. Just about the only chick in rock I really liked was Chrissie Hynde.

I heard you met her last year.

Yeah, there was this rumor that she was going to appear during the encore of an Urge Overkill show at [New York’s] Irving Plaza and I was in town, so I went down there. After Urge Overkill finished, they introduced a special guest and it was Chrissie Hynde and they did “Precious” and man, I was almost in tears. The whole muddy, ugly sound of Urge Overkill just automatically cleared up. The sound system itself sounded better. She just did one song and it was so cool, so amazing. Anyway, there was this after-show party at a bar around the corner and I went over and Ed [“King” Roeser, Urge bassist] was with Chrissie and she’s drinking tequila out of a bottle in her purse and making out with him pretty heavy in the booth. I guess because Ed’s girlfriend person or whatever was in the bar, he started encouraging me, really encouraging me, to come over and meet Chrissie. I guess he was trying to finesse the situation or something. And I’m like, you know, “This doesn’t seem like the right time, Ed,” but I sat down next to the booth and he’s trying to interrupt this makeout session with Chrissie Hynde to introduce me. So finally he pulled away from her and said, “Chrissie, this is Kim from the Breeders.” And Chrissie looked up, kind of confused, and said in this slurred voice, “You’re not a chick, you’re a dude.” Then she reached out and grabbed my boob. So I’m in shock, right, and I guess Chrissie got embarrassed, because then she grabbed my hand and put it on her boob, like it was a boob-off or something. I don’t know why I had to touch hers too, but I just got up and left, it was awful….Actually, though, looking back on it, I’m kind of glad that she didn’t turn out to be all nice and down-to-earth. She was kind of an asshole and I kind of liked that.

Did you think she’d know who you were?

Oh, I don’t know why she would have. I just didn’t think she would be a gender person. I don’t know why it was important to her whether I was a girl or a guy, but I guess it was.

Do you think that Veruca Salt rips off the Breeders?

No, I don’t really think so, although I’ve heard people sing the chorus to “Seether” and change the words to “sounds like the Breeders.” I think it’s just because they’re two girls with dark hair. Their guitars are mixed completely differently, their vocals are higher up….But I could never not like Veruca Salt because I read an interview with them where they said they went to the Cabaret Metro in Chicago to see our show and that it was a “profound and enlightening experience” or something, and this was before they started the band. They said they just looked at each other, equally beaming, and “the room was filled with love.” They were also asked if they hated being compared to the Breeders and they said, “Oh no, we just hope they don’t hate us.” So I just want to say right now, “No, we don’t hate you, girls.”

There’s a stirring in the back bedroom and Kelley emerges with a blanket, curls up in a chair, and yawns. Jim Machpherson exclaims, “It’s Alive!” But Kim Doesn’t acknowledge her sister, instead staring at me. Awkwardly, I plunge back in, asking how often the band members get recognized in public nowadays.

“We live in Ohio,” Kim says blithely, “and when we go to some place in Ohio, nobody knows the Breeders. There might be two 15-year-old girls in the mall who know who we are.”

Machpherson fidgets and says, quietly, “Ooh, I don’t know about that.”

Kim looks surprised. “Why, do you guys get recognized a lot?”

“We do now,” deadpans Kelley. Kim sputters out a laugh.

“Mostly I get the high school kids,” says Macpherson. “You know, all the cute little high school girls, eyeing me when I’m in my car. Then I open the door and they freak out when they see I have two kids and a wife.” Kim and Kelley share a giggle, followed by a silence as they teasingly glare at each other.

Kim: “So do you wanna ask Kelley questions about her thing? Are you allowed to talk about it?”

Kelley: “No comment. My lawyer says I can’t say anything.”

Kim: “You’re going to go up.”

Kelley: “No, I’m not.”

Kim: “They’re going to send you up. We’re touring without you.”

Kelley makes a pouty face.

“So, what’s up with the case?” I ask somewhat innocently.

Suddenly, Kelley brightens up. “They’re writing a motion to suppress evidence right now. And the judge is concerned about three things: One, is that someone who worked at the Emery office opened the package and evidence was tampered with. Second, my house was searched without a warrant, they put me in handcuffs and took me off to jail, but when I asked for a lawyer, they didn’t give me one, that’s the third thing.”

Kim, who’d gone to the kitchen to put on some soup for dinner, sticks her head in mischievously. “Cheeseballs, anyone?”

“They announced my address through just about every media outlet you could imagine,” continues Kelley. “They showed my house on TV so cars could drive by and honk and kids could come up to the door, which was actually kind of cute. Plus, I got a lot of mail.”

Kim scoots in from the kitchen. “Oh God, we got this letter sent to my parents’ house and it was this crazy guy saying, ‘Jesus died on the cross for Kelley Deal, call me if you need help.’ He was like, ‘I’m not a Jesus freak, but we’ve been worried about you for a long time.'”

“And the really freaky thing,” adds Kelley, “was that the address was like two doors up from my parents’ house on the other side of the street.”

Kim returns to the kitchen, obviously trying to maneuver us toward dinner, but more Kelley talk ensues, and you can tell that at a certain point Kim wishes her sister would just clam up. Eventually, Kelley tires of telling stories about being on the road with the Frogs, heads back to her bedroom, and dozes off for the evening. Slightly weirded out, Kim and I finish our dinner and resume chatting.

You’ve said that there’s nothing inherently wrong with drugs, it’s the social circumstances around them. But have you ever done drugs to the point where it damaged your work?

Cigarette smoking. I’d sing better if I quit smoking.

What about heroin and “harder” drugs?

No, I’ve gone through my periods of chronic use, but it was never an acute problem.

After Kurt and Courtney, do you feel that alternative rock has become synonymous with romanticizing heroin?

You know, one thing that’s pathetic about it, and one thing that I thought about heroin addicts and junkies when I was younger, was that they were free to do whatever they wanted. Well, when I was 19, I was hanging out with this addict. He shot up in an artery in his wrist and lost a couple of fingers. And what I noticed with him was that with all this talk about going here and going there and maybe visiting in the spring, despite all that talk, he was tied to whatever town he was in, because that’s where his dealer was. He couldn’t leave for any length of time to do anything. So what we should be doing, instead of glamorizing junkies, like with that offensive, stupid Matt Dillon film [Drugstore Cowboy], what we should be doing is showing how fucking boring junkies are. They’re like little old ladies who need their medication and can’t be away from a doctor too long. But unlike little old ladies, after awhile, they can’t get anybody to give them money, and they run out of money and they’re not free and wild and experiencing life through drugs, they’re delaying life. These young, sexy 22-year-old junkies aren’t doing shit.

Did you ever get really fatalistic and depressed this winter? I remember one interview last year when you just walked out on a balcony and stared into the distance and said, “Life. I thought it was gonna be better.”

Oh, that was ridiculous. That was the fucking Rolling Stone article, and they wanted me to say all this deep stuff and it’s like, finally, I just said, “Life sucks sometimes,” you know, and I’m standing with the sunlight in my hair. (Kim goes over to the open front door with the ripped screen and poses, gazing into the yard, smoking her cigarette Marlene Dietrich-style, and affecting a Continental accent). “You know, Charles, I’m suffering through a bit of ennui right now. Really, sometimes, I feel as if life just… sucks.” When she closes with a flourish, Macpherson stands and applauds the performance. “Thank you, thank you,” says Kim, with a wave of an imaginary hanky. “Hey,” she continues, turning back to me, “life sucks, it’s true, but that’s okay. I mean, didn’t you think it would be better than this? Is that a new thing to say? There have been loads of good parts, but come on.” Winding her up, I mention that the scene on the balcony was just this perfect tragic-romantic vision, like she was starring in a Truffaut flick or something.

“Oh, fuck you, Charles.” She sticks out her tongue.

Macpherson chimes in: “I actually had a tear in my eye, as well, Kim.”

Collapsing back onto the sofa, Kim mutters, “Shitheads,” and then breaks into her widest smile of the day.

What’s refreshing and also exasperating about Kim Deal is that she’s completely off-the-cuff, unpremeditated. Unlike Courtney Love, she has no specific agenda; she’s still figuring things out as she goes along. Which means that her opinions—and she’s always got a fistful—can get sloppy. She’ll rant, for no particular reason, about how the call-and-response in hip-hop and funk is “stupid fucking bullshit,” then go off on how sensitive white boys who try to understand women’s issues are more sexist than rappers who say “bitch” or “ho,” and think the latter has something to do with the former. She’ll berate the phoniness of feminists and middle-class college kids, but then praise sexist, working-class guys for “not trying to be something they’re not,” in a way that only a middle-class college kid would. Sometimes it’s as if Kim wants us to believe that she and Kelley were never more real than when they were making those truck drivers get all misty over Hank Williams songs.

But no matter how careless she may be about strangers, when it comes to her family, and especially Kelley, Kim is genuinely devoted, if occasionally at a loss. She doesn’t want anything to harm them, and to that end, she left this message on my answering machine after I got home from Dreamland: “This is Kim Deal, I want to talk to you about something. It’s about the piece you’re doing on us. We’ve had a little bit of a breakdown. Kelley’s no longer with us, and I have an idea, but you have to do it with me, to help her, but…so call me, bye.” When I reached her at her parents’ house, she hesitated and said, “Urn,hold on a second, let me talk to my dad.” Then she hung up and called back later.

According to Kim, the future of the Breeders is uncertain. Since the end of Lollapalooza in September, Kelley had been periodically using heroin. A family intervention in January, which Kim thought successful, proved otherwise. The Dreamland sessions fell apart after Kim found Kelley stretched out on a sofa in the TV room, kicking in her sleep. Kim pulled aside Kelley’s boyfriend, who acknowledged that she had begun using again. “When you left, it got stupid,” Kim told me later. “She was high, and not only was she high, she was really high, dropping-her-bagel high. It was rude.”

After Macpherson drove Kelley back to Dayton, she and her father boarded a plane to Minnesota, where she was admitted to a rehabilitation clinic. The album was on hold. But Kim hadn’t just called to give me a progress report; she was frantically worried about the emphasis of this article. As she’d alluded to earlier, she didn’t want Kelley falling into the trap (cf. Kurt and Courtney) of seeing her name in print and believing that music plus gimmicky drug history equals stardom.

“I feel like anything having to do with Kelley and her little drug thing, anything in print, she’ll look at it and feel like she accomplished something,” Kim asserts. “And I’m trying to get it through her head that that’s bullshit….She has no life right now, she has heroin. She has to understand that she gets her life back if she gets off heroin. This shit is not to be laughed at or scoffed at. This is really important to me and my family. You don’t know what it feels like, it’s so horrible to have to watch your twin sister, your best friend in the whole world, lose her self-worth, lose her self-esteem, lose all sense of who she is, lose everything. It’s the worst fucking feeling in the world.”

It’s been written that every happy family is the same and that every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. But that’s all just bad poetry when you suddenly realize you can kick your father’s ass anytime you want, or when your twin sister and best friend develops a drug habit. Repulsed by “family values” rhetoric, but needing to find comfort and compassion somewhere, many people are in search of, for lack of a better word, “alternative” families. When you get down to it, that’s what most subcultures in this country have always been about.

I was reminded of this on a late Sunday night in the TV room at Dreamland, when I stayed up with the Tammy and the Amps crew— minus Kelley, who was still asleep back at the house—for the MTV “world premiere” of the Guided By Voices video for “Auditorium/Motor Away” on 120 Minutes. If you ever wanted an example of the sacrifices that we make for families, alternative or otherwise, this was it. Treated to the drolleries of Matthew Sweet for almost two hours, we waited as it became obvious that GBV would be the night’s final video. In the meantime, we saw thenew Veruca Salt clip, about which Kim commented, “This is another video I don’t understand.” To which Macpherson replied: “It’s about Levolor blinds, Kim.” Faith No More’s latest was greeted with cries of “What the hell happened to these guys?” and Kim squirmed through the Beastie Boys’ “Hey Ladies.”

Finally, it was time for Guided By Voices, or Guided By Beers, as they’re known in this circle. Sweet introduced the group as being from Dayton, hometown of the Breeders, adding that Jim Greer was not only a rock critic but Kim’s husband. Everybody laughed and congratulated Kim, who actually blushed, and when the video concluded, we all applauded. Greer phoned in for a post-game wrap-up, Macpherson poured some wine, and even though I was an outsider in every way, I felt like I was welcome and comfortable in someone’s else’s home. It was a nice feeling. Too bad Kelley wasn’t able to enjoy it.