The whereabouts of Joakim Bouaziz’s worldly possessions are currently unknown. To be more precise, they’re somewhere between Paris and New York, packed inside cardboard boxes which are stacked on top of palettes which are lined up inside a shipping container. The whole bulging shebang is either on a boat or, he suspects, sitting in a warehouse in New York, waiting to clear customs. The French musician sounds remarkably calm about not knowing where it all is, despite the fact that the bundle includes tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of recording equipment, not to mention some several cubic meters’ worth of records.

“Honestly, I don’t even know how many,” says Bouaziz, speaking by phone from his apartment in downtown Manhattan, on the border between Chinatown and the Lower East Side. “I never counted. It’s like three — two and a half, maybe, or three — of those Ikea shelves, the big ones.” He’s talking about the Expedit, a shelving unit so revered by vinyl lovers that a Facebook campaign to save the product was launched not long ago, when the Swedish furniture behemoth announced that it was phasing out the design. By “big ones,” he means the 5x5s. Each of its 25 slots holds roughly 100 pieces of vinyl, so that’s 2500 records per unit. Three of those, full of records that are almost certainly cooler and rarer than your records, all boxed up and displacing a commensurate amount of seawater as the ship plows its whale-road all the way from France to New York, where the Statue of Liberty will greet their arrival with her torch held aloft, as she has greeted the arrival of so many newcomers to our shores.

But the records, he clarifies, are just a small part of the move. The studio gear — that’s the bulk of the load. And boy, he isn’t kidding. That becomes immediately clear if you watch Future Music‘s virtual tour of his Parisian studio from a few years back. Once it has cleared customs — and you can practically hear him wince when I tell him how much I had to pay in customs duties when I shipped my own record collection, perhaps half the size of his, from the United States to Germany, and I wasn’t shipping a whole recording studio on top of it; hopefully, he says, the Americans will be more lenient than the German bean-counters — all those records and synthesizers and sequencers and samplers and drum machines and rack-mount effects boxes are destined for a studio that Bouaziz is building in a former garage in Gowanus, Brooklyn.

If all goes well, it will be a dream studio, suitable for producing bands as well as solo electronic music, and “more professional,” he says, than his former studio in Paris, where he has recorded acts like Poni Hoax and Panico for his own Tigersushi label, as well as acts like Paris’ soulful house bricoleurs Acid Washed and the Giallocore revivalists Zombie Zombie, whom Lady Gaga sampled on “Venus.” It helps that he’s been working with this guy who knows his shit, a guy whose resume goes all the way back to the ’70s, including stints at Electric Ladyland, the New York studio that gave the world Arcade Fire’s Reflektor, Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories, Patti Smith’s Horses, and a goodly chunk of Led Zeppelin’s catalog. “He’s a super-pro,” says Bouaziz.

As bootstrap stories go, of course, it’s not exactly arriving at Port Authority with $20 to your name and a dog-eared copy of Playbill stuffed in your pocket. But making it in New York isn’t going to be easy, either.

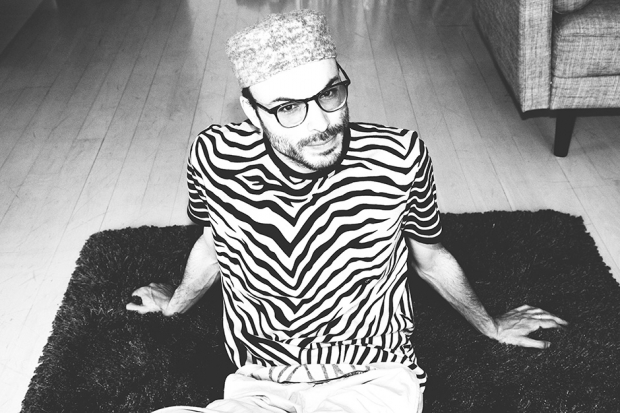

Among other things, the 37-year-old musician occupies a sort of grey area that, while hardly unfashionable, isn’t exactly popular. His music is often song-based, but it’s definitely not indie rock. It’s electronic, but it’s a world away from the kind of adrenaline-fueled festival bangers that currently define America’s youthful taste in EDM. While he’s French, his music has always been stranger and smarter than, say, the Ed Banger crew, or even Daft Punk.

That’s not to say he doesn’t have his fans. “For me, everything he’s been doing is exactly what I’ve been wanting to hear,” says Tim Sweeney, a New York DJ and host of the weekly radio mix show Beats in Space. (Bouziz recently appeared on the show, playing a synth-heavy set of classics and rarities: Severed Heads, Silver Apples, Flash and the Pan, Tones on Tail, and even Neneh Cherry’s shortlived group Raw Sex, Pure Energy.) “He straddles the line between weird, out-there music and something with a pop sensibility. It’s music that is both challenging and interesting. Weird and fun.”

That also goes for the music he puts out on Tigersushi. In the 14 years since Bouaziz founded the label, he has taken it from an idiosyncratic outlet for forgotten alt-disco rarities and turned it into a home for a motley crew of electronic-music misfits like cryogenic cyber-funk experimentalists Principles of Geometry, minimal techno defector Crackboy (Krikor Kouchian), and the unrepentant electro-pop nostalgic DyE. And in a scene marred by its machismo, Tigersushi is notable for its support of women artists, including Korea’s Nakion, former New Young Pony Club member Lou Hayter and her project the New Sins, the multimedia artist Sir Alice, and even, way back in the early days of the label, the Japanese shrieker MU, of “Paris Hilton” fame.

His activities extend beyond the music scene, too; he has collaborated extensively with the French artist Camille Henrot. For her 2006 installation piece The Minimum of Life, he recorded (and sometimes plays live) a noise soundtrack inspired by Throbbing Gristle and Wolf Eyes, and he explored funk and hip-hop in his contribution to Henrot’s installation Grosse Fatigue, an exploration of creation myths, archival logic, and cascading browser windows for which she was awarded the Silver Lion award at least year’s Venice Biennale.

“I think he’s working towards a personal but complete vision of music — his own unifying theory,” says Adam Bainbridge, a.k.a. Kindness, who collaborated with Bouaziz on “No Time to Waste,” released last year on CRWDSPCR. “Maybe he’d disagree, but I see it in the thoughtfulness and energy he devotes to his work, and to other people’s.”

Joakim’s new album, Tropics of Love, certainly lends credence to Bainbridge’s unifying-theory theory; it pulls together multiple strands of his work — the sonic experimentation, the alt-pop songcraft, the bittersweet emotion, the effortless fusion of high and low — into perhaps the most elegant expression he has managed yet.

“I always think his music has a chance of crossing over to the mainstream,” says Sweeney. “Maybe this album will be the one. Maybe it won’t. I just hope at some point people recognize what incredible stuff Joakim has done. Maybe it will be 20 or 30 years from now, but it will happen.”

It startles me a little to hear this, because it echoes so closely my own feelings about Joakim, right down to the now-familiar burst of optimism that accompanies each of his albums — Surely, this will be the one! — followed by the inevitable letdown when said album goes all but unnoticed.

“I guess when you devote yourself to promoting your artists as much as yourself, your career suffers,” says Bainbridge. “I would argue that being musically ambitious and unafraid to re-invent yourself also works against you. It takes a dedicated, equally sophisticated audience to see the rewards in a moving target. Plus he’s extremely tall and French, and shorter, non-French people are generally intimidated by the extremely tall and French.”

Bouaziz was born in Paris, but when he was six years old, the family moved to Goupilliéres, a small village (pop. 480) an hour’s drive from the center of Paris. His father traveled to and from the city every day for work, but Goupilliéres is less bedroom community than countryside idyll, complete with stone cottages, dewy fields, and a church dating to the 12th Century.

In the mid-1990s, while Bouaziz studied piano at the National Conservatory of the Versaille region, his younger brothers were immersing themselves in the rave scene. “It’s not that they got me into techno, because I didn’t like what they were listening to,” he says, “but they had turntables, and I was buying records, like, Mo’ Wax and Warp stuff. I remember not being able to beat-match two records. Like, how does this work? It’s impossible!”

If a certain kind of outsider status has been a recurring theme of Joakim’s music, perhaps some of it has to do with his age: born too late to have experienced firsthand movements like Krautrock, post-punk, and acid house; born too early have grown up with the universal accessibility to all kinds of niche music (and all eras of music, period) that YouTube has facilitated.

Ironically, Tigersushi was initially envisioned not as a record label, but as a far-reaching Internet enterprise designed to offer just that kind of access. Long before “music discovery” was a buzz term on internet execs’ lips, Bouaziz envisioned a website that would combine an encyclopedic repository of music-related information with streaming and downloadable music — a kind of hybrid Allmusic and Spotify, but nearly a decade before Spotify ever launched. You can still find traces of Tigersushi’s early ambitions archived via the Wayback Machine; a snapshot from 2002 turns up a lesson on No Wave, a review of David Bowie’s Hunky Dory, and a short post comparing the sleeve of the Clash’s London Calling with Elvis Presley’s self-titled 1956 debut LP.

Bouziz and a friend spent nights “just scanning records and writing reviews and biographies of artists,” he recalls. “I wrote a huge story on industrial music, and Krautrock, and hip-hop. Every time, it was a really historical approach, like where does it come from, what are the key records, what was influenced by this, et cetera.” In other words, an approach very much like the one that the label itself would take. Compare, for instance, Tigersushi’s 2004 compilation, So Young But So Cold: Underground French Music 1977-1983, a compendium of post-punk and leftfield synth-pop (Richard Pinhas, the (Hypothetical) Prophets, Metal Boys, et al) featuring liner notes by the veteran French journalist and punk musician Patrick Eudeline.

In retrospect, Bouaziz and his buddy may have bitten off more than they could chew — some of those early articles, published in both French and English, suggest an editorial team whose abilities, and translation skills, were stretched to the limit — but in any case, the market wasn’t ready. Bouaziz says, “We wanted to have a subscription system, so we went to see labels, and everyone was just shutting the door on our nose. It was 1999, 2000 — the Napster days — and the Internet was still the big, big enemy. Nobody would trust us.”

Out of this boondoggle, a record label took shape. In fact, the first Tigersushi releases were intended primarily as promotional tools for the web company. A series of 12-inches called More G.D.M. paired archival tracks from artists like Cluster, Max Berlin, and Gina X with new material commissioned from contemporary artists like John Tejada and Metro Area. (The title, short for More God Damn Music, was a play on Gina X’s 1981 single “No G.D.M.,” a new-wave disco classic that Joakim re-edited for the third 12-inch in the series.)

“One side was a reissue, and one side, a new artist, because we wanted to connect things,” he says. “That was really the philosophy of Tigersushi, to say, ‘Maybe you like this today, but do you know there was this before? And maybe you like this old music, but did you know that this comes from there?’ So we started doing the same thing with the records. The first one was Cluster on one side, and we thought, ‘OK, John Tejada made this one track we really like, and it sounds kind of Clustery; let’s ask him to do a track for the 12-inch.’ Then we did Gina X and we asked Metro Area, who were doing the first kind of disco-y, new-disco thing, and so on.”

As licensing deals failed to materialize, they slowly quit developing the editorial side of the website, he says, “because it was so much work for nothing, basically. And then the label became the only income for the company, so we just kept on doing records. It became a necessity, in a way. And we enjoyed it! Releasing that first More G.D.M. compilation, we got a lot of attention. Also, back then, there was not so much reissue product like that. It became much bigger a few years later, with Soul Jazz and Strut, but before, there was not so much. So we had a lot of press and attention for the first compilation. And we got a lot of demos really quickly. Then we signed our first artist. But before that, we hadn’t even thought of signing artists. It was just like, ‘We’re going to reissue things.'”

Three years ago, Joakim kicked off his fifth album, Nothing Gold, with a sweetly wistful song called “Forever Young.” Over a nervous flutter of keyboards, the chorus — “You used to be young / Where do you belong?” — expressed the kind of ambivalence you don’t hear too often in electronic dance music, what with its emphasis on late nights, boundless energy, high chemical tolerance, and the infinite deferral of anything approaching regret.

Much like James Murphy, Joakim has long found inspiration in the complicated relationship between youth, music, and the vagaries of the cool. His 2003 album Fantômes vacillated between druggy abandon and record-collector cred, mixing up minimalist house and synthetic disco with elements of Krautrock, tropicalia, and musique concrete. Three years later, Monsters & Silly Songs trotted out tersely funky dance-punk rave-ups like “I Wish You Were Gone” — a song as catchy and as punchy as anything in the Rapture’s catalog — as well as muddle-headed psychedelia and modular-synth fuckery; titles like “Peter Pan Over the Bronx” suggested an ongoing search for the Fountain of Youth.

By 2009’s Milky Ways, a pattern of sorts had developed, a kind of bait-and-switch game: Reel ’em in with shimmering, seductive pop songs like “Spiders,” then pull the rug out with quixotic studies like “Fly Like an Apple” (Captain Beefheart at the disco) or “Glossy Papers” (Stax meets Silver Apples?). In retrospect, it was a transitional record — just check “Back to Wilderness,” the eight-minute drone-metal opener — but it has held up better than most artists’ marginal albums, and it also offers crucial clues as to the contradictory impulses that have always driven his music. At the time, he said that the inspiration for the album had been the idea of youth as a kind of paradise lost — a mythical, utopian state. “It probably has to do with getting older,” he told me in 2009. “It’s always linked to something personal. Probably I think I’m not grown-up enough, being a 33-year-old guy. It’s between nostalgia and the refusal to lose these things, or to forget.”

Now 37, he asks whether growing up is really that hard to do after all. Tropics of Love is his sixth album (in 1999, before he adopted the Joakim alias, he recorded a jazzy, broken-beat record as Joakim Lone Octet), and it feels both like a summing up and a new beginning. Above all, it feels effortless, which is surprising, given the circumstances behind its creation.

Joakim gave up his apartment in Paris and moved to New York in January, 2013, but he had already been shuttling back and forth for two years before that, since around the release of Nothing Gold. “Since it was a very sort of transitional period, I’m not sure I had a precise idea of where I wanted to go with the new album,” he admits.

The majority of the album came together in a room in his Manhattan apartment, using a pared-down selection of machines that he shipped over from France in advance of the full move. There was an E-Mu SP-1200 sampler and drum machine; a Korg MS-20 synthesizer, one of his trusty, go-to instruments; and a set of modular components racked into a suitcase-like box. (Modulars are something like the craft beers of electronic music, but Joakim is no snob; he also used a Korg M1, a digital workstation from the early ’90s that remains the top selling synthesizer of all time, and whose glassy buzz gives the album its air of cozy approachability.) The whole setup was a world away from the carefully arranged banks of gear in his Paris studio. In a photograph of his improvised studio that he recently posted to Facebook, the SP-1200 is perched atop a cardboard box and a Technics turntable sits on a chair; a tabletop laid across sawhorses brims with patch cables and effects pedals, more evocative of the noise scene than nu-disco.

“The tools I use, the instruments I have, are very much part of the process,” he says. “I’m very attached to the tools. It’s a big inspiration for me. So being here in the studio with that drum machine and the modular synth and the M1, those things sort of gave a direction to the record. The early-’90s sampling sound — dirty, 12-bit sampling; the New Agey pads of the M1; and then the modular synthesis that I started to get really into.”

The watery “Laser Fingers” recalls Thomas Dolby’s “One of Our Submarines,” and “On the Beach” — a cover of Neil Young’s 1974 lament about a rock star who just can’t deal anymore (“I need a crowd of people / But I can’t face them day to day”) — is rendered as a slow-motion electro dirge, like Kraftwerk strung out on barbiturates. Its weary futurism would be perfectly suited to a film reboot of Nevil Shute’s post-apocalyptic novel of the same name, come to think of it. Even “Bring Your Love,” featuring the Rapture’s Luke Jenner, cradles a melancholy sensibility beneath its sunny chords and windswept effects. The whole album, in fact, feels pretty darn downcast.

“That’s funny,” says Bouaziz when I tell him this, “because I had an interview a week ago with a guy who was convinced that it was a very bright record, very happy. I was like ‘Really? You really think so?’ ‘Oh yeah!’ I was really surprised. It obviously depends on how you listen to it, but I think it’s probably a bit darker. You think it’s less pop? I thought it was more accessible, but I’m always wrong when I think how accessible my music is. I tried to do something simpler, with less instruments and less stuff, going more directly to what I want to do.”

At least on the first third of the album, this makes sense. “Bring Your Love” is among the most immediately gratifying songs Bouaziz has ever written, and the somber “Laser Fingers,” a collaboration with Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh (of the group Dragons of Zynth; he’s also the voice on the soundtrack to Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue), is, formally, a pretty straightforward example of instrumental electro-pop. It may be more nuanced than the vast majority of 1986-referencing, acid-tinged synth ditties these days, but it’s unlikely to leave many listeners feeling flummoxed, either. The slow-motion synthesizer ballad “Heartbeats,” likewise, has the easygoing feel and sumptuous harmonies of someone like fellow Frenchman M83, and hell, that guy’s scoring Hollywood movies these days.

But beneath the pop-oriented openness, there are darker, shiftier qualities at work. The rumbling “Chapter 2” gestures to the blasted ambient-industrial dread of artists like the Haxan Cloak; “Chapter 3” pays homage to Delia Derbyshire; and the closing “Hero,” despite the title, sounds like a tribute to side B of David Bowie’s Low — 10 minutes of gurgling electronics slowly giving way to dawn-like chords, a portrait of optimism at its most abstracted.

“There’s some weirder moments,” acknowledges Bouaziz. “But it wasn’t that I wanted to do something less pop or more pop; I just thought that I shouldn’t care. I thought of the Knife doing a record with one ‘song,’ and the rest is just weird, experimental things. I thought, ‘They don’t care. I shouldn’t care.'”

The centerpiece of the album, both literally and thematically, is a song called “This Is My Life.”

The premise is simple: Over a fantastically bouncy drum-and-synth groove — think Gershon Kingsley’s “Popcorn,” but made by tossing a fistful of gold ingots into a particle accelerator — a computerized voice reads off important milestones in Bouaziz’s biography:

In 1976, I was born in Paris

In 1978, I drowned in a swimming pool in Miami

In 1981, I fed my brother with a cigarette

In 1983, all my favorite Italo songs were recorded

In 1986, I fell in love with a Vietnamese girl…

There are quite a few girls involved — one gets the sense that Bouaziz may be something of a hopeless romantic — but the tone is light and the milestones, such as they are, appear to be largely inconsequential. (“In 1993, I started to wear lumberjack XL shirts. In 1994, I saw the woman of my life on a speeding train.”) It’s less a Bildungsroman than a flipbook of blurred snapshots, both arbitrary and otherwise.

Quite unlike LCD Soundsystem’s “Losing My Edge,” a song it superficially resembles, there isn’t an ounce of one-upmanship implied in Bouaziz’ musical recollections, which are limited to listening to Jimi Hendrix on the school bus in 1991, seeing the Wu-Tang Clan live in 1997, and purchasing his first two Warp records in 1995. (My favorite moment from the whole thing: “In 1996, I failed trying to mix those two records.” I’m someone who, in 1997, tried to learn to DJ by mixing Squarepusher with Amon Tobin — a fool’s errand, believe me — so that one struck a chord.) The song it most resembles is Daft Punk’s “Giorgio By Moroder,” in which the Italo-disco icon recounts stray moments from his own life in similarly low-key terms.

“This Is My Life” isn’t a real autobiography, of course. You could learn more about Joakim’s career by reading Wikipedia. But I find it both incredibly moving and refreshingly unguarded. As its 135-BPM quasi-acid sequence really gets going — oscillators squealing, ring modulators creaking like platinum bedsprings, trim piano-house chords offering halcyon echoes of Ibiza, circa 1988 — the beat drops out and the harmonized chorus kicks into high emotional gear over a rush of backwards reverb:

This is my life

What will you do with it

How do you change it

How do you stick to it

What is the price

Of holding onto your dreams

I just want to try

To keep feeling true to it

We won’t give up

We won’t give in

On paper, it looks kind of corny, I’ll admit it. It reads like self-help pop, like Up With People, like fucking Journey, for crying out loud. Don’t stop believin’! But there’s something about hearing those sentiments coming from an impossibly tall, impeccably dressed French dude that helps land it. Not to mention that chorus: vocal harmonies stacked to the heavens, the rhythm just a hair faster than it should be, so that your heart feels like it’s going to burst out of your chest, and your heart is a small, fuzzy animal and your chest is made of glass and everything is shot through with rainbows and insulated with dandelion tufts — my god, it’s kind of a moment! And it works! And for the nerds among us, seriously, when was the last time you heard a retro-not-retro piano-house jam that was more effective; when was the last time you heard a modular synthesizer squeal with quite that degree of gritty pathos?

I won’t shit you, as a 43-year-old man who frequently worries that his best years could be behind him, this song has become kind of a big deal for me. As someone whose relationship with music has gone awfully stale in the past year or so, this song actually makes me feel kind of alive. Kind of optimistic. Kind of like, gee — maybe I’m not the only person who wonders what it’s all about, and what’s the point, and wouldn’t it be nice, for fucking once, if this were my year?

Before it crests the precipice of pure, unbridled bathos and turns into a rainbow-flavored cascade — in the best way, I hasten to add — the song’s chronology cuts off rather abruptly. The final bullet point, before the chorus kicks in, is from 2005: “I decided to become an adult.”

But wait, what was that thing about him drowning? Or anyway, almost drowning? Yeah, that happened.

In fact, it is the first thing he remembers, he says: “That’s my first memory of anything: I remember being underwater, at the bottom of a swimming pool.” His family was on vacation in Miami; his mother, paralyzed with fear, was powerless to do anything about her young son, who bumped against the bottom of the pool and stared up at the rays of the sun as it bobbed in a chlorine haze, impossibly out of reach. And then, at least as Bouaziz remembers it, or at least as the story has been handed down in the family, his father appeared, dove in the pool, and fished the boy out.

“But I don’t remember it being —” he says, and pauses. “I was not stressed. I think that I didn’t realize, being a baby, that I was drowning. But since then, I have a strange relationship to the water. I don’t like it that much. It makes me sad, kind of. Especially open water. After that, there was another experience I could have put in the song: We were on the boat with my parents, a friend of theirs, and that friend said, ‘You know, kids, to learn swimming, you just have to throw them in the water!’ And then he throws me in the ocean. My parents were like, ‘What are you doing?'” He fairly yells the last part, incredulous, laughing a little bit, too.

“But I don’t remember that.”

Maybe Joakim’s two bad experiences with the water — almost drowning as a baby, and then getting thrown off a boat into the ocean, a few years later — primed him in some weird, primal way. “Sink or swim,” as they say, and that seems to be sort of his strategy for New York. Incredibly, Bouaziz’ visa is only good for three years. He’s hopeful that he can renew it, but jeez — that’s a big “if.” The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service isn’t exactly known for its leniency.

When I ask him about this, he laughs.

“I’m not thinking about that yet. It’s been complicated enough, so I don’t want to think about moving again.”

In any case, France holds little appeal for him right now. “You can just read the news,” he says. “I mean, the economy is bad. The political situation is horrible. People are depressed. There was an article in Le Monde recently about how many young people move from the country and they don’t come back. There always used to be students going abroad and then coming back. Now, they don’t come back, because they don’t see any perspective. I think Europe is at the turning point. People don’t see a bright future; they kind of gave up.”

“Maybe it’s easier when you’re abroad,” he concedes, “because I don’t care as much about American politics as I do French politics. But French politics really bums me out. All the things that have happened lately” — he cites protests against gay marriage, immigrants, the environment — “it’s really shocking to me.”

(The day after the European parliamentary elections, when Marine Le Pen’s extreme-right National Front party wins a shocking 26% of the vote, Joakim will tweet, “Vive la France,” accompanied by emoji of a pistol pointed at an un-smiley face. The meaning, I’m pretty sure, is something like, “So much for ‘Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.'”)

In contrast, he says, “I always liked New York. I thought, if I don’t do it now, I will never do it. It’s also a bit of a challenge: ‘A new career in a new town,’ like David Bowie says.”

And that challenge, of course, goes straight to the heart of “This Is My Life,” particularly its emo-to-the-max chorus, I tell him.

“Now we get to the depressing part,” he says, and laughs. “I was reading this article about OutKast at Coachella and people were saying, ‘Yeah, you know, they can’t compete with Zedd and his million watts of stroboscope and fireworks. They’re over.’ And I was like, this is so depressing that people can have such a discourse about music! If you don’t have a crazy-fireworks EDM show, then you’re not relevant. No, but this song, yeah, I remember when I was a teenager, I already had notebooks and I was already writing ideas and stuff that I didn’t want to forget. I already had the feeling that growing up, there’s a lot of compromise that you need to do, of course, but you have to remember certain things that make your life meaningful and remind you why you’re doing things and why I’m making music. So that’s something I always had in my mind since the early teenage years: trying not to give up and not to forget why I am doing this.”

Right now, anyway, there’s no time to worry about all that; there’s a studio in Gowanus that needs building. And the zoning, not to put too fine a point on it, is turning out to be a pain in the ass. “I have to do everything by the book, so it became a crazy nightmare,” he says. “It’s just the city — New York is insanely complicated and stupid when you try to build something. They make everything the most complicated possible. I don’t know why. To the point where it’s just absurd, but I have to do it. Maybe if I knew how complicated it would be, maybe I wouldn’t have moved.” But he did, and so here we are.

Sink or swim.