Fabulously rich and slightly lost, Giorgio Moroder decided to build a pyramid. “It was some years ago,” he says, slipping into a reverie. “This structure was planned for Dubai. Oh, it was going to be huge. It would’ve been empty in the middle with apartments all along the sides — just beautiful. I spent two years designing it. I wanted to do that instead of music.” He sighs and shakes his head. “So much time chasing stupid things.”

Moroder, an Italian who looks a bit like a suave Joe Biden, is sitting with his dewy, ringlet-haired wife Francisca amid olive trees and under a retractable glass roof at Spago in Beverly Hills on an opulent spring evening. He’s been coming here since the restaurant — which he named; Wolfgang Puck is an old friend — opened in 1982, back when he was arguably the most successful music producer in the world and an in-demand film composer with one Academy Award and two more soon to come.

Our waiter, a pinched, pinkish man with the unidentifiable accent of a Bond villain, arrives with menus, purring, “So glad to see you, Mr. Moroder. It has been too long.”

Moroder, blessed with the warmly dignified bearing of a benevolent duke, scans the menu. “Things have changed, guapito,” he says to his wife.

Francisca frowns. “They don’t have the Jewish pizza anymore.”

A waitress in a crisp white shirt and black apron, her rigid aura and pursed lips bringing to mind a moonlighting dom, places an oyster amuse-bouche in front of Moroder as he wearily recounts the projects he undertook during his decades devoted to whimsy.

“I made a cognac; it was really quite good. I had an idea for a technologically advanced luxury watch. I got involved in digital art and neon painting and put on shows of my work. I designed a sports car, the Cizeta-Moroder, with Marcello Gandini from Lamborghini; he did the Countach, of course. The Cizeta cost $600,000, but we could bargain — if a Japanese businessman says he wants it for three, fine.”

In the past year, though, spurred by Daft Punk’s Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo, two musicians who share his interest in dance music and pyramids, Moroder has rebooted.

“When the news came out that Daft Punk did a song with me [Random Access Memories‘ ‘Giorgio by Moroder’] all of a sudden I started getting calls from management companies. I got an agent for DJing when I’ve hardly ever DJ’d before in my life. I got an offer to do an album from a major record company — I can’t say which. David Guetta loves me. I’ve spoken with Avicii. Two months ago, not one of those people was talking to me. Daft Punk has given me credibility.”

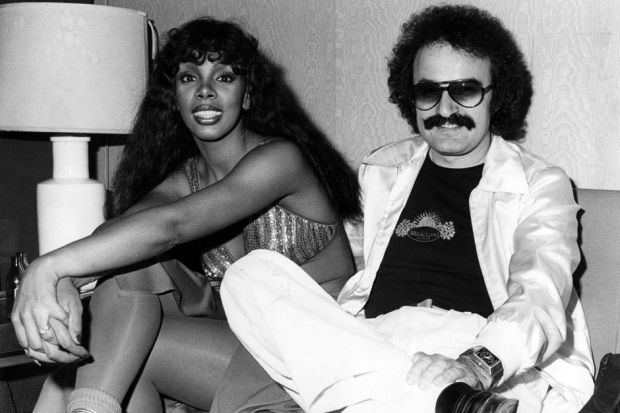

For more than a decade, Moroder was at the top of every hit-hungry schmoozer’s call list. Beginning in 1975, when he cowrote and arranged Donna Summer’s breakthrough disco come-on “Love to Love You Baby,” and through to his work on the Top Gun soundtrack in 1986, this soft-spoken man uncannily anticipated and sleekly satiated the desires of the music-buying public, and in so doing altered the trajectory of pop, dance, and film scoring. Aside from his collaboration with Summer, Moroder produced and cowrote hits for David Bowie, Blondie, Janet Jackson, Sparks, and Freddie Mercury. Which is like noting that Michelangelo did some solid doodles away from his work on the Sistine Chapel. He made ’80s-defining songs with small names (“What a Feeling” with Irene Cara, “Take My Breath Away” with Berlin), and generated anthems for global pageants — in 1984, he co-wrote and produced “Reach Out,” the official song of the Los Angeles Olympics. Four years later, he was called upon again for the Seoul Summer Games, producing proto K-pop confection “Hand in Hand” for the group Koreana. (Both are classics of panhuman kitsch, and exceptional accompaniment for jazzercising in legwarmers.)

Movies were also within Moroder’s domain. The moody, electronic scores for The Social Network, Drive, and Christopher Nolan’s Batman films are essentially tributes to the music Moroder composed for Midnight Express (1978), American Gigolo (1980), Scarface (1983), and Flashdance (1983). He also produced and cowrote the theme song for 1984’s children’s fantasy picture The NeverEnding Story (sung by an English chirper named Limahl, the former lead singer of Kajagoogoo), which despite having willingly heard it twice in 25 years remains forever stuck in my mind, much like the ill-fated horse Artax in the Swamps of Sadness.

This music — indeed, all of Moroder’s best music — has a 26th-century cybernetic gleam, a sweeping sense of melodic drama, synthesizers that signify as state-of-the-art even when they’re not, a deep beat, and an eager-to-please-ness that only could have been produced by a robot programmed to appeal broadly but who is still waiting on plug-ins for irony and cool. Or, say, a European. That such a description could fit the work of Europop-inflected chart champs Calvin Harris, Guetta, and Dr. Luke, as well as countless Italo disco, house, and trance club kings is testament to how deeply encoded Moroder’s default settings have become.

This content is no longer available.

“The way Moroder was pushing synths with live instruments and a four-on-the-floor beat invented the language that I’m using now. You can easily draw direct lines,” offers Dr. Luke, frequent producer for Ke$ha, Katy Perry, and countless others.

Movers and shakers slightly closer to the margins also caught the Moroder virus. “When DFA [Records] started, people like [LCD Soundsystem’s] James Murphy and myself were saying the name Moroder a lot,” says house DJ and producer John “The Juan” MacLean. “He was a model for us. You could hear him taking the electronic innovations of people like Kraftwerk and doing the arguably more innovative thing of putting those sounds into a pop context. It was, and is, incredibly inspiring.”

It’s also easy to argue that Daft Punk’s mysterious image was prototyped by Moroder, who for much of his career hid his face behind black sunglasses and a resplendent black mustache. The cover of his entirely digitally recorded, vocoder-heavy 1979 solo album E=MC2 showed him holding his jacket open to reveal an Iron Man-like torso of dials and glowing guts.

Google has enlisted Moroder to soundtrack Racer, a new mobile game for tablets and smart phones. And on May 20, as part of the Red Bull Academy Music Series in New York City, Moroder performed his first-ever American DJ set — further evidence of a culture coming back around on one of its chief architects.

“I set a Google Alert for myself and now I’m seeing people say my music influenced them and how great it is all the time,” says Moroder, poking at the puny mollusk. “Sometimes I listen to this stuff that’s supposed to be influenced by me and I can’t hear myself in it. But I’d rather they say it than not. It used to be just occasionally I’d read these things.”

What does this atmospheric change mean for Moroder?

He slurps his oyster and smacks his lips. “It means I’m back in business.”

Giovanni “Giorgio” Moroder was born the son of innkeepers in Ortisei, a small town in far Northern Italy in 1940. Giorgio’s three brothers liked painting and sculpting, but he liked music. At 15, he bought a guitar; at 19, he won his parents’ blessing to give up schooling and try to earn a living as a musician. For years, he sang pop covers in sleepy coffee shops, peppy originals in discotheques, and played stand-up bass in grand alpine ballrooms.

Because he enjoyed tinkering with a primitive tape machine, he moved to Berlin in the mid-’60s to take a job as a recording engineer. In those days, the profession was still dominated by lumps in white lab coats who saw a shaggy haircut, let alone a lavish mustache, as a warning sign. Moroder found the job, and the city, “like a prison.” In Berlin, “the Wall meant it was hard to leave when you wanted to and the engineers were all so conservative. I liked to experiment; if there was a new machine, I wanted to get it and see what it could do. Setting levels in a studio was too boring.”

After a few years of feeling fenced in, Moroder moved to Munich because it was closer to Ortisei. In 1967, he produced some bubblegum tunes — which the Germans called Schlager music — for a dusky Lebanese-French pop poodle named Ricky Shayne. The songs sold well, and Moroder’s career was off, though not quite running. A natural behind the recording console, he stubbornly kept stepping into the spotlight, writing and singing catchy and cleverly arranged candyfloss dross that made the Archies sound edgy.

His genius for melody and arrangement turned much of that material into respectably successful singles — the cream is compiled on Schlagermoroder Volume 1, released in April by Repertoire — but Moroder was pushing up against his performing limits. His voice was thin, and even as a young man, he looked middle-aged. Still, the DNA of his later successes can be found in such curious collections as 1972’s proto-disco strudel, Son of My Father. “That was my first record where I used synthesizer,” Moroder explains. “I’d met a classical composer in Munich, Eberhard Schoener, who had a Moog and showed me how to use it. I was absolutely taken — it sounded totally new. I decided I needed to figure out how to use Moogs and sequencers and synthesizers in commercial music.”

At the same time Moroder was futzing around with these high-tech tools, two bands of Germans, Kraftwerk in Düsseldorf and Tangerine Dream in Berlin, were using the same machines to evoke, respectively, robotic romanticism and interstellar safaris. The keenly curious Moroder released his own highly experimental electronic record, 1975’s Einzelganger, which sold squat.

“The way I know if something works is if it sells,” says Moroder. “When I heard Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, I thought they were doing some interesting things, but there was no strong melody. After Einzelganger, I wanted do more with synthesizers and I wanted it to be popular. I needed an extra element, something more human. ”

So, he added orgasms.

Donna Summer was an expatriate American musical-theater singer living in Munich when she came to Moroder’s attention while doing session work at Musicland, the studio he opened in the bottom of a hotel complex. (Musicland would eventually host T. Rex, Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Queen, Electric Light Orchestra, and other British rock stars with an extreme aversion to paying U.K. taxes, before Moroder sold it in 1979.)

“Donna had a very sexy and soulful voice,” says Moroder. “She was obviously great-looking. You need that combination of talent and image. I never had that before, and I couldn’t have predicted finding a beautiful black American singer in Munich. She made the music hot. I was incredibly lucky.”

If the 17-minute version of Summer’s first Moroder-helmed disco single, “Love to Love You Baby” — recorded for Casablanca Records and filled with the singer’s pulse-quickening erolalia — was the warning shot, 1977’s “I Feel Love,” with its sequenced bass and rippling synthesizer, signaled that the future had arrived. Moroder’s solo groove LP, From Here to Eternity (released the same year), was similarly epochal, though for DJs and producers rather than dancers.

Moroder went on to captain six gold and platinum albums and nine No. 1 Billboard dance hits for Summer before the singer left for Geffen Records in 1980.

“Hearing his stuff with Donna changed my whole mind about playing dance music,” says Chic’s Nile Rodgers, himself a disco godhead and Daft Punk collaborator. “Giorgio’s groove and syncopation were so tight. He’s the guy who made the synthesizer move. Prior to him I wasn’t interested in getting people to dance. I was doing hardcore jazz fusion. Then I heard this modern-sounding music that was so funky and I thought, ‘I can now make dance music and hold my head up high.'”

Once he’d found his sound, Moroder worked fast. “Giorgio was always trying to get out of the studio,” recalls his protégé Harold Faltermeyer, a Musicland session keyboardist who went on to compose the electronic scores for Fletch and Beverly Hills Cop (Blame him for “Axel F”). “One time, he told me and [drummer] Keith Forsey and [lyricist] Pete Bellotte, ‘You all go into a room and compose a song, then when I come back, we’ll record it.’ And I said, ‘So, Giorgio, what are you doing then?’ He said, ‘I’ll be playing pool.’ He wasn’t one to linger on a song.”

In 1978, British director Alan Parker asked if Moroder would score his prison nightmare film Midnight Express. “I remember seeing that movie and thinking, ‘Why hasn’t anybody done this before?'” remembers Hollywood composer Hans Zimmer, an Oscar-winner for The Lion King. “If you put electronic sounds up against scary images it gets ten times scarier because with live musicians you can instinctively tell when the tension in the music is going to break. With Giorgio’s synthesizers, it’s this inevitable stream of notes coming at you. The viewer never knows when something is going to alleviate the tension. He did absolutely brilliant, revolutionary work.”

Zimmer adds that when he built a new synthesizer to use for The Dark Knight Rises score, he named it Giorgio.

Moroder’s work on Midnight Express was the first all-electronic score to win an Academy Award and compelled him towards Hollywood, both the place and state of mind: He moved to L.A. in the early ’80s and bought a vast white mansion he dubbed the Ice Castle. He invested in restaurants and had weird encounters with iconic oddballs. “Sylvester Stallone, a real gentleman, asked me to do a song with Bob Dylan for Rambo III,” shares Moroder, who’d previously scored Sly’s 1987 bicep-epic Over the Top. “I went over to Bob’s house in Malibu, this gorgeous all-wood place, and played what I’d written. He was talking about the message of the movie and saying it wasn’t right for him with all the Russians and politics. Those kinds of meetings were common. It was a wonderful time.”

This golden era felt eternal. “I knew how to make hits,” Moroder says matter-of-factly. “Sometimes, I only used the synthesizers a little, like with Blondie [on 1980’s ‘Call Me’]. Other times, they were the key to the song. Even when disco went out, I could still make hits. Once I had so much success, every idea became concentrated. I had so much confidence. I knew how the bass should sound, what rhythms would work. The tempos I knew: 110 to 120 BPM. I knew they would dance in the clubs in New York or anywhere. You can’t be sure what songs will take off, but it was almost like I had a magic formula.”

Until the magic went boom, bap, and gone.

The elevator opens into Francisca and Giorgio’s apartment on the 21st floor of a Westwood high-rise. Through the floor-to-ceiling windows, the Santa Monica Mountains sprawl spectacularly in the distance. “At night, when the lights from the houses are all that you can see, the view reminds me of Ortisei,” says Moroder wistfully.

The Moroders have been living in this rented space for three years, having sold the Ice Castle when the mansion began to feel forbiddingly large. Candy Spelling, the widow of television mogul Aaron, is now a neighbor, although a reported $600 million fortune isn’t enough to make her smile at Francisca in the lobby.

For two years before she died (in 2012, from lung cancer), Donna Summer lived here, too, a couple of floors down. She and Moroder had grown apart after she’d switched labels. “David Geffen pushed her to make music that wasn’t right for her. It was a big mistake in my opinion,” says Moroder, who produced two slightly commercially disappointing Geffen albums for Summer before Quincy Jones took control on 1982’s Donna Summer.

Divergent personal beliefs turned that professional fissure into a fault. “Donna became quite religious,” says Moroder, as he strides past a wall of gold and platinum records. “She made me record a dance song about Jesus, dear God. And she really did not like gays — her attitude was sometimes difficult in the ’80s.” (Summer has denied ever making anti-gay statements.) “We were never ‘estranged,’ but for a long time we did not have the relationship we once did.”

Towards the end of Summer’s life, Moroder says that they would talk and text often after she moved into the building. “I saw her more in those two years than I had in the previous 20. It was lovely.”

[ooyala code=”9neHJwdTqPGktZpIBaqW84kCxo7ApKlY” player_id=”8bdb685537af477d8cd5ea1ebd611511″]

We walk through Moroder’s living room. A painting of his — an abstract azure wave — dominates one wall, though the neon-light strip running through it has gone out. Thigh-high ochre vases line the floor by the windows. On top of a white piano are photos of Moroder with Venus Williams and Raquel Welch. His Oscars and Grammys fill a small end table. I ask where he keeps his stereo. “I don’t have one. I never listen to music at home, only what I’m working on. I listen to pop radio when I drive. That’s it,” he says.

We take a seat at the long glass dining-room table. Francisca brings Moroder some orange juice. I ask about the slow-down in his discography that began in the late ’80s and continued till, well, now.

“Rap was a big part of that,” he says. “I had no idea about it. None at all. I could hear it was new, but I could never have produced it well. I didn’t understand a word they were saying. I’m not a street guy; I’m not urban. I had no feel for it. I don’t know if I would say I was out of step, because I recognized this music was exciting, but I was not willing or able to make it myself.”

He gives a classic Italian whattayougonnado shrug. “I was okay with this change. I’d done enough. I’d done everything, really. I was sick of hanging out in studios anyway.”

The cosmic joke is that Moroder’s music was enthusiastically adapted by hip-hop. Tracks by OutKast, DJ Shadow, Raekwon, Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, Kanye West, Beyoncé, to name a few, were built on Moroder samples. Those folks knew what to do with his music; he just didn’t know what to do with theirs.

“It doesn’t matter who you are,” reasons Nile Rodgers. “There comes a time when music moves on. That’s nature. They say mathematicians and musicians have similar brains. The idea is that you peak as an idea generator, as a creative person, around 30 years old. Albert Einstein came up with all his best stuff in his twenties, and I wrote all my biggest hits between the ages of 25 and 27. The fact that Giorgio kept having hits into the ’80s is an amazing exception. Hip-hop definitely derailed a lot of people, but there are other reasons why Giorgio might have felt uninspired. No one is endlessly adaptable by himself. You need good collaborators.”

Moroder leads me to his home workstation: Two computer monitors and a keyboard are on a desk. To the left of the desk is a vocal mic. Hanging on the wall to the right is a blank white canvas spotted with burn holes, a piece of art by his son, Alessandro, 23. On the wall facing the monitors is a large, digitally altered photo of Summer. “I changed the color of her eyes,” says Moroder.

Believing that pop music has curved back towards him (“It’s all European disco on the radio now,” he says), Moroder has been asking singers here to record demos of songs that he hopes to send out to labels, publishers, and artist managers. Amanda Warner, of synth-pop act MNDR, sang with Moroder earlier this year. “The whole time you’re looking at him and thinking, ‘That’s Giorgio Moroder,'” she says. “The rest of the time, you’re trying to please him. He’s very hands-on about getting the performance he wants. That’s a rare thing now, when everyone is sending digital files to each other. His music has this amazing electronic sheen, but fundamentally, he’s trying to get a human performance out of you.”

Moroder scrolls through a drive looking for a file. “I’ve never been organized. I don’t label anything in a smart way. There are Donna Summer recordings that no one knows where they are because I put them somewhere and never found them again.”

He finds the file and plays a song that sounds very much like a Giorgio Moroder song, full of strobing synth flash and disco kick.

“Who are the big up-and-coming pop stars that I should tell my manager to connect me with?” Moroder asks. He has many questions like this. Should he have a Twitter account? Should he post material on Soundcloud? YouTube? What’s the point of a Facebook page?

(There are “Giorgio Moroder” accounts on both Soundcloud and Facebook. Neither is legit. That said, whoever is posting on the “official” Facebook page should keep it up: Moroder likes your work.)

Ultimately, consumer-facing questions are secondary. He needs to reach the creators. It’s nice for historically aware hitmakers to bow, but folks other than Daft Punk need to offer a hand if Moroder has any hope of playing the game at the level he used to.

“This business is a copycat business. If the Daft Punk record takes off, then you’ll see more and more people interested in Giorgio and his work and I might be out of a job,” says Dr. Luke, wryly. “If that doesn’t happen? Look, even for the hottest producer at a given moment, this business is completely unpredictable. It’s not easy. A lot of times you need someone to give you a break.”

Someone like Dr. Luke? “It depends on the project. I’d love to talk to Giorgio.”

Back in his apartment, Moroder plays me another new song. A synthesized bass line begins to boogie. He starts tapping his foot and I follow. Four on the floor. Works every time.

“Who do you think would be good to sing on something like this?” Moroder asks eagerly. “I could imagine Katy Perry. Of course, Rihanna is a major talent.” He looks out the window, searching for more. “Lady Gaga, she has a great voice. Who else? Nicki Minaj.”

Moroder turns up the volume. “Tell me,” he says, now bouncing in his chair, scanning horizons in his mind, “Will they dance to this in New York?”