On Monday, James Brooks, formerly of the electronic-minded duo-turned-solo-project Elite Gymnastics, debuted his new alias, Dead Girlfriends, with a four-song EP called Stop Pretending. One song, ‘On Fraternity,’ immediately attracted a goodly amount of Internet praise, including an impassioned Pitchfork write-up; though the solemnly sung, noise-damaged track sticks to the ungendered second-person pronoun ‘you,’ critics and fans assumed that with lines like ‘The way your heart speeds up when you notice someone walking behind you’ and ‘In their opinion you were always kind of asking for it,’ he was addressing — or even trying on — a woman’s everyday fear of rape and harassment.

Brooks has since clarified that his new work is partly inspired by Grimes, the art-pop project of girlfriend Claire Boucher, and in particular her 2012 song ‘Oblivion,’ which also addresses sexual assault. (He’s also explained that the moniker Dead Girlfriends is inspired by the work of militant feminist Andrea Dworkin.) But from Tumblr to Twitter, criticism has come just as quickly as praise, taking in everything from the confrontational band name to the song’s allegedly tepid sentiment to the oddly detached video to the general feeling that writer and critic Michelle Myers politely but pointedly summarized as ‘I’m uninterested in having a watery paraphrasing of the words I’ve been screaming for years sang back to me in a male voice.’

So here, we’ve asked Myers to join a roundtable of fellow culture writers and thinkers to discuss the controversy around ‘On Fraternity,’ but also address the more general phenomenon — stretching back at least as far as Fugazi’s “Suggestion” — of well-intentioned men singing and speaking for women’s experiences in their work, and the difficulty of doing so without lapsing into condescension or “mansplaining.” Also joining the roundtable this time are frequent SPIN contributor Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, Village Voice writer Brittany Spanos, Maura Magazine founder/editor Maura K. Johnston, Maximum Rock n’ Roll columnist and feminist blogger Jessica Skolnik, and Vibe columnist Hilary Crosley.

JESSICA HOPPER: Michelle, you had a lot to say about this, and even inspired a response from Brooks himself on Tumblr — do you feel it’s his place to address women’s rape fear in a song, and do you think that’s what he’s doing?

MICHELLE MYERS: My initial impression of ‘On Fraternity’ was that James Brooks was describing how women feel living under the constant threat of sexual violence. Because he used second-person pronouns, I felt as thought Brooks was telling me how it feels to be a woman — and his observations seemed to be superficial takes on women’s fear of assault. I assumed Brooks was paraphrasing a few well-known clichés about female terror he knew secondhand, and passing them off as his own observations.

I’m wary of male feminists who are trying to prove how much they ‘get it.’ I realize it’s frustrating to hear, but no amount of learning or empathy will let you know what it’s like to live every day as a woman. I think there is a very real space for men to speak their truth about how patriarchy hurts them. I am interested in how masculinity and gendered violence affects their lives, as opposed to than hearing men tell me what I already know about rape culture firsthand. On the other hand, it’s possible that Brooks is not attempting to write about rape culture or the female experience at all, but is rather trying to explore a more universal fear of violence. He never specifically mentions sexual assault, nor does he use gendered pronouns. However, by naming his project Dead Girlfriends and aligning his Internet persona with feminist ideas, he invites these interpretations. He set up the expectation that his art was about violence against women when he invoked Andrea Dworkin and used phrases like ‘asking for it’ in his lyrics.

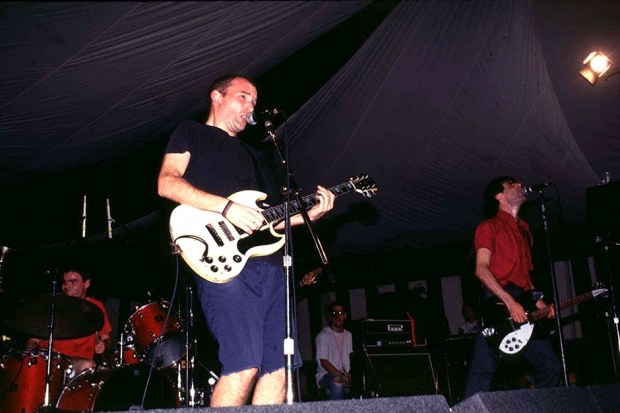

JESSICA HOPPER: Historically speaking, Fugazi were held up and even celebrated for essentially doing the same thing on “Suggestion,” which is kind of the standard-bearer expression of male feminism in punk. Jessica, did you find ‘On Fraternity’ offensive? How did you interpret what Brooks is saying?

JESSICA SKOLNIK: I found it to be sweet and genuine. “Suggestion” was actually in the back of my mind as I parsed out my thoughts about it: Did I feel that I was being spoken for, particularly as a rape survivor?

It’s incredibly important for marginalized people to own our thoughts and stories, given how many times a day the work done by marginalized people is lifted and blown up by those with greater privilege and power. But I didn’t feel like that was what Brooks was doing with ‘On Fraternity,’ despite the fact that the theme is a well-worn one. There is a lot of room to move here. The “you” Brooks speaks of could be of any gender, and it could be one specific person, a small group, a multitude. It was refreshing to me to hear lyrics that could apply to a wide number of experiences with rape culture and the omnipresent fear of violence, rather than attempting to distill one experience and universalize it. Experiences with rape culture vary based on race, gender, sexuality, economic status, and other positions.

I also think it is telling, and fortunate, that Brooks does not attempt to insert himself into this narrative other than as observer and narrator: Instead of attempting to assume a woman’s experience in this song, he seems to be trying to get at that greater truth, that multiplicity of experiences that make up the pattern we call rape culture. Given his citation for his sources in past interviews, I do not get the feeling that he’s trying to profit off his privilege and the work done by people more marginalized than he, but that he is trying to make something sincere out of something painful he has observed time and again.

BRITTANY SPANOS: Michelle mentioned appropriation in her initial Tumblr post, which mirrored my initial thoughts on the song. As a woman of color, I’m a pro at being wary of white-dude guilt. However, I see Brooks’ motivation and this song as coming from a very good place that isn’t seen too often in pop culture, and I find that to be meaningful. Brooks’ song exists within the realm of storytelling to me. An artist working through something that unsettles him or her is important. It’s also very easy to find yourself unsettled by the idea of a man empathizing with an experience that is so closely associated with being a woman — though not just experienced by women. “On Fraternity” exists in a much different time than when Fugazi released “Suggestion,” obviously. If “Suggestion” came out today, I think we’d be exposed to many more critiques of it.

Jessica, you had been tweeting about the idea of taste not aligning with ideology in regards to enjoying R. Kelly’s music, and I think that applies recently to “Blurred Lines” and other songs of that ilk. I think that’s what I’m constantly working through with all of the pop music I love. “On Fraternity” works against my belief that an experience that is inherently part of one’s gender, culture, race, or orientation is most powerful when expressed by the person of that gender, culture, race, or orientation — but I admire his use of storytelling to express it.

Julianne, do you think there have been moments like that, when a song by someone outside a group attempted to reflect the experience of that group, and pulled it off?

JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD: Whether a person can write from a perspective not her own? I would say absolutely: For instance, The-Dream, while not a visage of feminist perfection, has written a handful of the most feminist mainstream pop songs in recent history, for women singers even. But some people are not successful. I appreciate Dead Girlfriends making an effort, and for blogging about feminism. But more often than not I would like to listen to some women opine about this feminist shit, and for the ostensibly down-ass men to, you know, hear us.

So last month, I interviewed punk and feminist icon Kathleen Hanna for an upcoming SPIN feature on her new band the Julie Ruin, and interestingly enough, we talked about “Suggestion.” I’d asked her about women of color being marginalized within, and by, riot grrrl; she expressed a lot of regret and remorse about that, and then we started talking about the idea Brittany brings up. Here’s her quote:

“I wanna admit that I’m not perfect, that I’ve made mistakes. I’ve written songs about police brutality, because when Amadou Diallo was murdered, I cried, and I went to tons of protests. That song may not be perfect, but you gotta stick your neck out. Or ‘Suggestion,’ by Fugazi. I have issues with Ian MacKaye — who I love — singing as if he was a woman. But that song changed my life, because it was the first time I ever heard a man singing about something that was predominantly a woman’s issue. I didn’t like the way he did it. I’m sure there are tons of people who didn’t like ‘Bang Bang,’ a song Le Tigre wrote — who are pissed about the way we did it — but we did it, and we put ourselves out to be criticized, and I hope that people criticize things that I said, because it’s all about the exchange. It’s not about being perfect, it’s about opening the conversation.”

Hanna’s response is the antithesis of “mansplaining,” of the way men often make every argument about themselves, even and especially if it’s unequivocally Not About the Men. She’s advocating the really logical, mature, yet ridiculously rare concept that we are culpable for what we put out into the world, and that as writers, musicians, artists, and even freaking Supreme Court justices, we might at some point have to answer for our shit. (Though it should be noted that Hanna’s song about police brutality is written from her own perspective.)

It’s the concept I tried to keep in mind in my response to Grimes’ Tumblr post defending the Dead Girlfriends song, in which she called a piece I wrote about her for Stereogum “fucking sexist,” because I respect her reality, and I obviously do not take that shit lightly. It’s the same care, I would hope, that Dead Girlfriends would take in response to my friend Claire’s much more recent piece about him for Stereogum, in which she wrote, fierce and true, about her reality, and how his music makes her feel pretty shitty. To bring it back to Kathleen Hanna’s quote, while I don’t like that Dead Girlfriends song — mostly the way he sings it, which sounds pat and disaffected, but not quite in the (pleasurable) realm of feminist boredom — at least maybe it is opening this conversation for wider topics. Like how almost every woman I know, including myself, has been affected by some form of sexual violence, and we’re regressing in so many ways across the spectrum.

MAURA K. JOHNSTON: In a blog post Brooks put up earlier today, he talked about how he didn’t intend for ‘On Fraternity’ to be from the perspective of a woman, nor did he want it to take the place of women making their own statements about feminism. I appreciate his clarification. The song is fine; its lyrics are obvious in a Tumblr-aphorism way. I probably will not listen to it by choice again, although the noise elements brought in to heighten the feelings of unsettledness bend my ear in a particularly convincing way.

What concerns me is how the regression of gender relations and the demands of the always-on news cycle have resulted in the reflexive response to men taking stances that are pro-women, yet barely radical by the standards of 20 (or even 30!) years ago, being the equivalent of a spontaneous parade with fireworks at the end. From the title on down, “On Fraternity” is a song about being a dude; that dude’s discomfort is highlighted, although like other people noted when the song first came out, the things he’s cold-shower-shocked by are realities that women live with as a matter of course. To paraphrase Shania Twain, “So, you noticed that women are treated like second-class citizens as a matter of course? That don’t impress me much.”

And I guess that’s what frustrates me about this debate, and the fact that I know the name “Hugo Schwyzer,” and other instances of Men Explaining Why Women Are the Way They Are. A lot of my thinking about online content has rested in the idea of the straight, white, cis male — preferably aged in the demographic sweet spot between 18 and 34 — becoming a “default” of sorts. Much of the lowest-common-denominator BS that appeals to “everyone” online actually targets this demo, and if the angle’s more Reddit-ready, all the better for it. (Geek culture! Comic-Con! FRIDAYYYYS!)

I don’t think it’s an accident that as this catering to young, straight, white men has been embraced by a heretofore-unseen torrent of media outlets all grasping for the same eyeballs, male-female politics have devolved into feminist bloggers engaging in ridiculously overblown, page-view-hoarding half-readings of song lyrics, with supposed adult males claiming that “reverse racism” and “misandry” are actual phenomena. At the same time, legislatures all over the country chip away at our rights to have autonomy over our physical selves. The debate that’s flared over the last couple of days has been a microcosm of this phenomenon: Actual social change is lost in the race for retweets, drowned out by the male voices that get privileged way too naturally.

HILLARY CROSLEY: Maura, fantastic use of Shania Twain. I miss her and her interlock braids at times like these. So Dead Girlfriends’ “On Fraternity” sounds like white male privilege trying to do right but ultimately looking like an interloper, and the song and the Internet backlash remind me of a few things. I thought of the artist formerly as Mos Def subjecting himself to Guantanamo Bay prisoner conditions to highlight America’s controversial incarceration practices: Despite his intentions, the demonstration just came off a bit… self-righteous. And this is how I see Brooks and his awkward anti-rape-culture song: It seems well meaning, but misguided. I don’t believe he actually knows how a sexual-assault survivor feels, so a musical poem from his perspective isn’t very effective, and it just all seems sort of attention-hungry.

Now, I could be totally wrong. Brooks could be coming from a pure, naïve place, as he tried to explain on his Tumblr, but with a name like Dead Girlfriends — unless I’m missing its deeper, spiritual meaning — I’m thinking he wants at least some attention. So, moving forward for Brooks, I’d advise giving strong but measured support to feminist principles and fights, volunteering at a crisis hotline, and keeping yourself from dipping into the womynist Internet Kool-Aid unless you a) have steeled yourself for inevitable “What are you doing in this conversation, MAN?” backlash and b) totally know the flavor.

JESSICA HOPPER: Aside from The-Dream, where are we seeing effective male feminism in pop? It’s been a long, hot summer (or, uh, lifetime) of rape culture up in our faces — do we even want some dude’s reflections on Steubenville up in our earbuds?

HILARY CROSLEY: I agree with Julianne. The-Dream is a beast when it comes to channeling a woman’s finger-wagging thoughts. But I don’t expect to hear him speak out about Steubenville or advocate for wage equality, because he’s an artist. Sort of like when Kanye West said, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people,” and then later admitted he just felt it at that moment, but he’s not a political activist. Maybe West is Dead Girlfriends’ spirit animal, and Brooks just wants to highlight illogical and dangerous behavior among men in a song — and a Tumblr post or two — and leave it at that? I don’t think we should eat him alive for that, but again, it’s all in the delivery. Still, I’m not much for just talking when it comes to things like social equality, I’d rather said artist be active for change with the awkward singing rather than just singing about said bad situation, awkwardly.

MICHELLE MYERS: I want more men to be feminists and try to understand how sexism affects us, but I also know that when they try to speak about patriarchy, no matter how pure their intentions, no matter how flawless their rhetoric, their voices will drown ours out. The best, most feminist straight cismale will always get more credit for his feminism than what the rest of us are saying. I’m sure Brooks doesn’t want it to be like that, but it is. There’s nothing I can do about it, and there’s nothing he can do about it. For that reason, I will probably always be a little suspicious of male feminism.

JESSICA SKOLNIK: The line between being genuine and being appropriative of trauma when you’re writing from a support role is a difficult one to tease out, though, and as art — pop included — is in reception as much as it is intention, I think it’s critical for those of us who find “On Fraternity” and songs like it genuine and enjoyable to listen with respect and understanding to those who found it appropriative, and to not shut them down. After all, a large part of rape culture is the silencing of survivors, the insistence that our feelings, if they don’t align with the status quo, are invalid. Survivors, and people who live directly with the threat of rape even if they haven’t encountered it yet, have varying experiences and interpretations, and it is key for us to support one another in these circumstances, even if we read the song in question differently.

JESSICA HOPPER: Do you think that with Kitty Pryde, Grimes, Sky Ferriera, and Angel Haze — female artists who are all being vocal about or making work about their experience with sexual assault — should dudes just sit the F down? Or do we owe Dead Girlfriends encouragement, in the hope that it encourages, rather than discourages, other men from considering how the patriarchy is crushing them as well?

MICHELLE MYERS: I hope that Brooks and other similarly inclined men continue to write about and make art that incorporates feminist ideas. My intention was never to shame Brooks into silence, but rather to question his methods. Part of being a male feminist is that when you make a misstep —even a small one — we’re going to call you out on it. I guess it’s a little unfair that once you declare yourself a feminist, we will scrutinize you even harder than before. But I don’t think the answer is giving every dude who calls himself pro-woman a free pass to make mistakes, just so they’ll want to be on our side.

JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD: Criticism is part and parcel of being an ally, like all you other brilliant chicas have said, and I think this goes back to Maura’s point about the conversation being centered around that oh-so-marketable 18-35 privileged white male demo: Those dudes’ free reign on the Internet and in life has made them feel empowered, and a lot of them tend to speak from a position of authority when they don’t yet know what they’re talking about — not just about feminism, but about rap music, politics, you name it. As for being gentler, I firmly believe it’s the role of the ally to learn all they can on their own before trying to speak for and even with the people they’re allying themselves with.

I definitely think we can go hard on men who claim feminism or who try to put forth feminist work — recall the well-meaning but totally bungled Lupe Fiasco “Bitch Bad” fiasco of 2012 — because, well, FEMINISM IS THERE BECAUSE WOMEN ARE MARGINALIZED BY MEN. That’s the point, dogs! Please join us — we want you here with us — but don’t get salty if your art sets off some of our life-honed bullshit meters. I really like Common’s song ” Faithful,” because it’s about him examining his male privilege and how he might act if “god was a her.” (Okay, that line is a twinge corny, but bless that dude.) As for men writing about rape, I mean, for one, Nirvana’s anti-rape song ‘Rape Me’ is written from the perspective of a victim — it’s seething and brutal, in ways similar to that awesome recent Patricia Lockwood poem. And I applaud those woman artists you mentioned for being brave enough to sing or rap or write about their experiences with sexual assault — because, as you know, 54 percent of rapes never get reported — and to their ranks I would add Tori Amos, Fiona Apple, Kathleen Hanna, and a million more I am forgetting. As a matter of fact, I want everyone reading this to go listen to Tori Amos’ “Me and a Gun,” trigger warning in advance, because shit is extremely real.

JESSICA SKOLNICK: We need to be very wary of the way men’s voices are received over women’s (and nonbinary people’s), and to be careful too, if we praise allies’ art, to directly refer back to the art made by survivors that paved the way for allies to speak up in this way. As someone who’s been writing about and making art out of my own trauma for a very long time, it’s really heartening for me to see so many younger pop artists — Grimes, Sky Ferreira, Kitty Pryde, and so forth — addressing their own experiences with sexual violence and in some cases making art from their experiences, because I know firsthand what a healing thing that can be. I also know what an incredible thing it is as a survivor to hear other survivors who you look up to and/or who are part of your community be open about their experiences: Rape is an incredibly isolating thing, and being public about it makes another person who is suffering feel not so alone.

MICHELLE MYERS: Since I wrote my original Tumblr post addressing “On Fraternity,” I realized that some of my frustrations with the song were a little misplaced, and that part of what I’m angry about is they way the media cycle flattens the diversity of women’s opinions. I was first aware of the song because of a glowing review from Pitchfork‘s Jenn Pelly: The song clearly spoke to her, which is totally legitimate. But I wanted to put it out there that as feminists and as female music writers, our opinions often differ wildly. When it comes to complicated art like this, there’s no one feminist response. I thought it was important for me to show that not every woman who cares about music unreservedly loved the song.

In my frustrations with my community, perhaps I was a little overly hard on Brooks. The controversy around “Blurred Lines” is another good example: A few women decided that song was sexist, and people assumed they were speaking for all of us. There’s a tendency for well-meaning men to listen to one female viewpoint, internalize it as the proper female response, and ignore any women who deviate from the party line. I want men to know that there is dissent and ambiguity among us, and being a male feminist isn’t just about finding the “correct feminist opinion” and then blindly disseminating it.