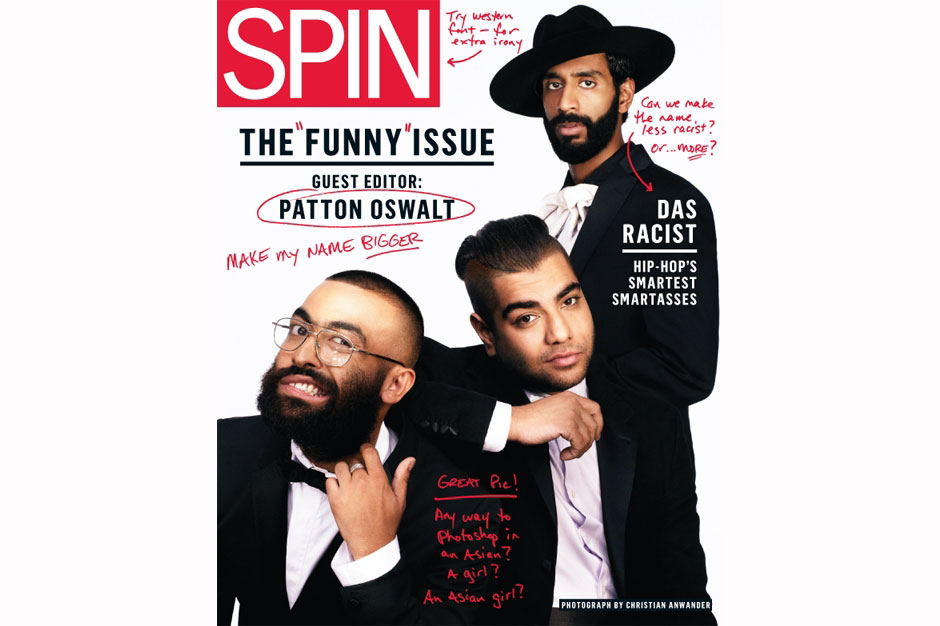

Why funny is deadly serious: Read guest editor Patton Oswalt’s introduction to SPIN’s first ever “Funny” Issue.

NOTE: I will refer to the Brooklyn-based rap trio Das Racist as “DR” for the majority of this story, both for convenience and to guard against the readership of this publication from either flipping to or clicking on a different article after repeated use of the word racist. (Yes, I am a writer of color, but feel free to pretend I’m white if it makes this paragraph seem less accusatory and more snarky. White people love snarky. Minorities reading this: We’re good, right?)

My little brother Ashok, or “Dap” as he is known and I refuse to call him, is DR’s hype man. His job is to know all the lyrics to the songs and enthusiastically repeat them onstage, often while dancing, which somehow makes my occupation as a professional comedian sound stable by comparison. This is reflected in how our relatives in India describe us to curious friends and neighbors: Ashok gets transformed into a “singer” and I become a “lawyer.” This is much more respectable, I suppose, than “crazy man who talks to strangers” (me) and “crazy man who yells at strangers” (Ashok).

When I was first told about my brother’s job, I didn’t know how to feel. Part of the confusion, I suppose, was that I hadn’t bothered listening to the music, despite knowing that my brother, his best friend since high school Himanshu Suri (Heems), and Hima’s Wesleyan University classmate Victor Vazquez (Kool A.D.) were performing regularly in Brooklyn and Ashok was excited about it. Part of me still sees Ashok’s existence on this planet as a result of my parents not wanting me to be bored. The possibility that he could have a life and destiny unconnected to my own seemed absurd.

Older siblings can be assholes.

According to the official description on their booking agency’s website, DR is “a white-guilt art project/science experiment/ponzi scheme piloted by Heems, KOOL A.D., and the Honorable Prophet Dapwell.” The inclusion of the word project at least is accurate: The music is, of course, the primary aspect of their work, with songs that seamlessly weave self-aware deconstructions of racial politics into a rapid-fire collage of pop-cultural, historical, and academic references reading both as poetry and comedy. There is also something inherently political about brown men (Ashok and Himanshu are Indian) who do not scan as black or white (Victor is half-black and half-white) talking about their place in a nation and an art form — hip-hop — that sees them as outsiders.

Hima expresses this frustration in the track “Shut Up, Man,” off their first proper album, Relax, released in September: “They say I act white, but sound black / But act black, but sound white / But what’s my sound bite supposed to sound like?” It is part of a trademark style of shrewd social observations and references to people, places, and things that add to a longer discussion only hinted at in the music. Their lyrics are a reading, listening, and viewing list for a later time — you can dance and nod your head to the music now, but if you want the full experience, start Googling.

After reading articles about DR over the past couple of years, the question that comes up repeatedly is: “Are they joking or are they serious?” This has followed them since 2008, when their song “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell” went viral. Was it simply a funny song about two friends going to the wrong fast-food restaurant, or did it say more about the state of American culture? Does the repetition in the song symbolize the Mobius-strip repetition of chains that appear throughout the country? Or something more? They officially responded in the song “hahahaha jk?” from last year’s mixtape Sit Down, Man, with the chorus “We’re not joking / Just joking, we are joking / Just joking, we’re not joking.”

“People who ask things like that are unfunny idiots who take themselves too seriously and don’t understand how jokes work,” Ashok has told me. You can be funny and say what you mean; these ideas are not mutually exclusive. Some of the best jokes came from people who meant it. See: Pryor, Bruce, Carlin, etc.

I discuss many of the same issues DR does in my comedy, including but not limited to: racism, colonialism, politics, and cocoa butter. We use jokes as a way to defend ourselves and to call out bullshit that angers us while attempting not to be corny or preachy. However, the last album I bought might have been Modest Mouse’s The Moon & Antarctica or TV on the Radio’s Desperate Youth, Blood Thirsty Babes. I am frozen musically somewhere around 2004. Compared to my brother, I’ve always felt like a 45-year-old “cool dad” (I’m 29 and childless).

It’s a mild Thursday in September, two days after Relax has come out and is currently, if briefly, holding at No. 3 on iTunes’ hip-hop chart behind Watch the Throne and Tha Carter IV. I walk into my brother’s railroad apartment in Bushwick, Brooklyn, which has become DR’s makeshift headquarters. Victor and Hima are on the couch, drinking tea, bleary from a long day of promo. Ashok is on his computer in the adjacent room, and pops in and out of the conversation. I give Victor a hug and rub Hima’s belly.

They are educated men of color, the children of immigrants from diverse and complicated places on both coasts (Victor from the Bay Area and Hima and Ashok from Queens). They are aware of the historical and social context of this moment, their place in it, and how to manipulate the media, which I am now, awkwardly, part of. I press record and stumble through the first question. I avoid eye contact initially because I worry we’ll all start laughing.

“You like Victor more than me,” Hima says later, joking or not joking. “You gave him a hug and you didn’t give me one. Why don’t you write about how you like him more?”

To be fair, Victor is extremely charming. Despite my mother having two sons and a husband, Victor is the only man who has brought her flowers for no particular reason. He already had some success fronting the electro-pop band Boy Crisis before DR started to take off. Victor’s job in DR is to be Victor, and he’s aware of this.

“I think I can do my own thing a little more because all that’s expected of me is to do raps and hooks,” he says. “I kinda liked playing with instruments, but it’s way easier to have a sense of dignity as a rapper because you’re not seen lugging an amp out of the place you just played. You can just bounce.”

Himanshu, on the other hand, doesn’t have the same kind of detachment. He is a 26-year-old former Wall Street headhunter with an interest in postcolonial theory, and much of DR’s success is due to his desire, shrewd marketing, and a business plan he devised as the group’s manager. When the time came to release Relax, the group decided to avoid major labels and release it on Hima’s own Greedhead Music. “There’s no white dude behind this band telling us what to do,” he says. This is his full-time job — he estimates eight to ten hours a day answering e-mails, tweeting, and building contacts. He has put DR and his nascent label in a position to succeed with the support of little more than a few friends and interns. The only tasks outsourced are their publicity and the distribution of their music (via Sony Megaforce).

For a self-made future music mogul, Hima is surprisingly accessible online, which, along with making their earlier work free, has earned fierce loyalty among fans. Ashok posts his phone number on his website and engages in long conversations with strangers. Also, Victor may hook up with you.

“I’m out there more than Victor when it comes to social media,” explains Hima, sipping tea, “but in person, I’m more reserved. He’s the consummate artist and rock star.”

Himanshu credits my brother with introducing him to a lot of music in their high-school years. Stuff like MF Doom, Pete Rock, and New York underground label Definitive Jux, as well as what Ashok describes as “My Bloody Valentine?type stuff.” In contrast, by the time Victor and Himanshu met at Wesleyan and started working together, much of their musical influences had been defined.

Though their lyrics indicate shared politics, their flows and style reflect a difference in personality and influences. Most rap groups tend to be from the same geographic region — this is the rare partnership of MCs from two different coasts, a defining characteristic of DR that Hima thinks gets overlooked.

“New York rap is louder,” he says. “Queens rappers are a little more agitated and a little less experimental in a way. Even from the beginning, I was working on beats that were more geared toward a larger audience.”

“I think West Coast rap is more adventurous and less concerned with the pretenses of living up to any specific ideas about rap as a genre,” adds Victor. “[Bay area rappers] Mac Dre and E-40 are talking about killing and robbing people and it’s still hella laid-back and weird.”

And you can hear those differences in how they rap: On “Rainbow in the Dark,” Victor says, “Just because I rock the secondhand Versace / Wash me, watch me / The second hand couldn’t even clock me.” In contrast, after his opening verse of the single “Michael Jackson,” Hima yells, “Yeah, I’m fucking great at rapping!” The line both cleverly mocks the need to brag in hip-hop while also brazenly doing just that.

While the importance of the dynamic between Hima and Victor becomes clear, I remained confused about Ashok’s role outside of vigorous yelling and jumping. On the business end, he built the DR website, the online store, and is responsible for all the visuals they use in their live shows. He’s also in charge of “digital media content,” including an Internet television and radio show he created called Chillin Island. Though he appears on the sketch “Sit Down, People” on the second mixtape, he doesn’t rap for DR. (Winky Taterz, his debut EP, will be out soon on Greedhead.) Ashok’s importance becomes clearer to me over the course of the interview. During a tangent about First World jobs, my brother goes on a brief monologue about the nature of work after the industrial revolution, our exponentially growing population, and how difficult it is to stay morally sound given such conditions. My little brother, who read almost all the books from my undergraduate career at Bowdoin College in three months, essentially provides Das Racist with their own professor. This explains why I hear Ashok’s “voice” in DR songs, even though he’s not actually in them.

I ask Hima and Victor why they often refer to him as a “spiritual advisor.”

Victor: “He tells us exactly what to do.”

Himanshu: “He writes our lyrics. He picks the producers. Everything. He’s the mastermind.”And then they laugh.

Instead of celebrating our father’s birthday, May 29, 2011, his two ungrateful sons, the singer and the lawyer, performed at the Sasquatch! festival in Washington. My set went better than expected, considering I was performing in front of many white people who had no issue wearing Native American headdresses and face paint and didn’t even have the decency to finish off the impression by being unjustifiably killed.

But it was the DR show later that day that made me happiest. My friend Ahamefule Oluo had arranged a six-piece brass section to play on several songs, but they had never rehearsed with the group. DR open with “Ek Shaneesh” off the first mixtape, which, like many of their songs, is fast and furious with references to anything and everything, including academic Gayatri Spivak, author Arundhati Roy, Persian poet Rumi, Richard Hell, and Anthony Bourdain. (The latter shout-out landed them on No Reservations and got them major cred from my mother.)

Ashok yells “Azuca!” repeatedly, in honor of Celia Cruz. Victor matter-of-factly asks the audience, “What’s up, white people?” Hima starts chanting, “Puerto Rico.” After claiming they are Yeasayer, they do a version of “Rapping 2 U” that ends with a couple of verses of Usher’s 1997 hit single “You Make Me Wanna…,” which continues until the crowd finally joins in.

After welcoming the brass section onstage, they do several songs. The classically trained musicians look terrified as they attempt to play music they barely know, while the audience is all too happy to comply with DR’s demands to chuck free festival-provided SoyJoy protein bars at the stage. It’s amazing theater. “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell” pops with the horns and includes the additional lyrics “combination Fed Ex and Kinko’s” and “combination Baskin Robbins and Dunkin’ Donuts.” However, throwing in “It was the best of times / It was the worst of times / It was the combination best of times and worst of times” is the highlight. The song ends with 30 seconds of screaming and horns blasting. It sounds like the world is ending.

In contrast, at the sold-out Relax album release show in New York City in September, DR rap as crisply as I’ve ever seen them. They have purpose and high energy from their first song. There are moments of humor and spark, but the show is more professional and polished. The chaos is missed, but it’s an understandable concession.

“If this is what I’m going to do, I might as well do it well,” Hima tells me.

During another headlining show in New York last year, Hima asked if there were any Indian people from Queens in the audience, and there was a huge roar. We’ve waited a long time to exist in the American mainstream and on our terms.

Himanshu and Ashok have been best friends since they were teenagers, attending New York City’s prestigious public high school Stuyvesant. I first met Hima in early 2001 when we saw American Desi together, a horrendous film about young South Asian Americans “coming of age” at a college in New Jersey that starred a pre-famous Kal Penn. Still, we were excited the film existed, considering our dominant image in American pop culture was Apu from The Simpsons, voiced by a white guy.

On May 3, 2011, Ashok and I did an edition of our mostly improvised, live comedy talk show The Untitled Kondabolu Brothers Project at the People’s Improv Theater in New York. It’s loosely structured so Ashok can go on long digressions, generally about the Illuminati and peak-oil theory, but then I can reel him back in to keep the show coherent. Our guest was Ajay Naidu from Office Space, one of the few South Asians who had been a visible presence on television and film when we were growing up. Another familiar face, Aasif Mandvi of The Daily Show, was also in attendance.

This was the day after Osama bin Laden had been killed. The moment was rife with bigotry and hostility, which Hima had illustrated by retweeting a barrage of racist comments. Things like “Ground Zero celebrations a ‘sandnigger’-free zone” and “RIP Osama bin laden, fucking hindu [sic]” provided fodder for Ashok and I to joke about and analyze. But as fun and cathartic as this was for us, Hima was drunk and depressed. The day brought back a lot of painful memories.

Stuyvesant was in Battery Park City, not far from the World Trade Center. The students both saw the second plane hit and the towers fall. They saw people jump out of burning buildings. They had to evacuate and escape on foot. Knowing what was on the way, Hima and Ashok and their friends organized the South Asian and Middle Eastern students with the goal of protecting the Muslim girls who wore a hijab. They were forced to think quickly to protect themselves from falling buildings and other Americans. The days that followed compounded their self-images as “outsiders” by labeling them — us — as “potential threats.” These are themes that are not just part of DR’s music, but explain their very existence.

“I don’t think about [DR] in the context of trying to figure out American racism or institutional racism,” says Hima now. “Everyone says we talk about race, but I just talk about being Indian.”

Relax is more accessible to a mainstream audience, and DR themselves refer to it as a “pop record.” It features a diverse roster of producers and guests, including Diplo, Danny Brown, Yeasayer’s Anand Wilder, Vampire Weekend’s Rostam Batmanglij, Chairlift’s Patrick Wimberly, and hip-hop revered MC/Def Jux cofounder El-P. The first single, “Michael Jackson,” has a Bollywood-inspired riff and a “Black or White”?inspired video with an infectious chorus: “Michael Jackson / A million dollars / You feel me??/ Holler!” The album also has a lot more singing on it than you’d expect, particularly in “Booty in the Air” and “Girl,” which feels like a New Edition song. Still, the title track features Hima talking about the conflict in Kashmir and his immigrant parents’ struggle in America. The first words are Victor’s: “White devils like it.” (We hope so!)

In Hima’s mind, the goals are uncomplicated, though the path may not be: “I want to make a lot of money,” he says plainly. “I mean, what am I supposed to do? Start a revolution? I’d like to provide for myself and others, here and in India, and just stay happy and not, you know, go crazy. That’s all I feel like I really owe anybody.”

Another thing that struck me about the release show in September was the lack of diversity in the audience. “I feel like the more it’s reported that white people come to our shows, the more white people will feel comfortable coming to our shows,” says Victor, “and the less that people who aren’t white will feel comfortable coming to our shows.”

When DR yell, “If you’re white and from the Upper East Side, go home! We don’t want you here,” it means more when there are minorities there to see privilege being flipped for a moment. I have the same feeling when I’m doing stand-up to a mixed crowd — there is catharsis. I want to play in that space between laughter and discomfort, and that is something DR do extremely well. Even the silliest song can have something sharp, powerful, and unexpected in it.

I don’t know how successful a group with DR’s personalities, style, and lyrical content can be, but anecdotal indicators are good. This summer I performed at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in Scotland. As I waited for the doors of my venue to open, I noticed three young men staring at me. I then overheard one of them say, “Is that him? I think it’s him. Should I say something?” I assumed they recognized me from my appearance on the BBC show Russell Howard’s Good News. Or perhaps this was one of those superfans who downloaded my Comedy Central special off a torrent. Strange, I thought, that usually happens to me in India.

One of the boys finally says something: “Hey, I just want you to know that we love your brother Dap.” His friend opens up his jacket to reveal DR’s limited-edition Mishka T-shirt depicting a genie with his head cut off.

“Yeah, me too. You’ll love the new record. It sounds amazing. Ashok’s hilarious in the music video for ‘Michael Jackson.’…” They look confused. “Dap is hilarious, I mean.”

They smile, nod their heads, and I walk inside. My ego looks a lot like the gruesome image on that kid’s T-shirt. But I’m proud.

Follow Hari Kondabolu on Twitter @harithecomic.

BUY THIS ISSUE

Read the entire November 2011 issue of SPIN.