In November, Fantasy Records will reissue the original version of Cybotron’s classic 1983 early Detroit electro/techno album, Enter — which previously had been reissued in 1990 in a different configuration under the title Clear — along with previously unreleased material (singles, B-sides, and alternate mixes in their full 12-inch versions). The following is partly excerpted from Dave Tompkins’ liner notes and his book, How to Wreck a Nice Beach: The Vocoder from World War II to Hip-Hop. Happy Halloween.

—

More space, Willy, more space soon!

— Wilbur Whateley of the Decaying Whateleys, The Dunwich Horror

Rik Davis has spent the afternoon blowing up trees. Deposited by helicopter, the Marine from Detroit squats in a blast crater somewhere north of Dong Ha, near the DMZ reaches of South Vietnam. It’s 1968. Ops and borders are fluid. Davis carries a chrome M-16, some C4 to heat his cocoa, and a leaflet picturing cheerleader smiles and soft drinks. On the flip side is a photo of a B-52 Stratofortress spilling bombs. This psy-op propaganda is intended to convince the Vietcong to defect while promising chieu hoi, “Open arms.” If the promise of girls, cola, and hugs couldn’t lure kids out of the jungle, faked necrophonic recordings of their dead ancestors — wailing from loudspeakers attached to backpacks and helicopters — were used for further persuasion.

Also Read

Compact Discs: Sound of the Future

Davis’ associations with his three-year tour of duty were no less phantasmic. When I spoke with the now-63-year-old Ann Arbor resident (and co-founder of Cybotron) over the phone, he summed up his Vietnam experience through H.P. Lovecraft, by way of his nose, in a desiccated voice. I wonder what I’ll look like when the planet is cleared off. The question originated with The Dunwich Horror but ended up with a Private First Class who invested his post-malaria, combat-disability pay in an Arp synthesizer and programmed it to replicate machine-gun fire. This is how Rik Davis dealt. A little bugg shogg y’heah from a guy who split his teenage years between riots in Detroit and getting shot at while peeling leeches in a remote jungle on the other side of the planet.

“I was not in the rear with the gear,” he says, deployed in time for the Tet Counteroffensive. While Davis was deforesting helopads in Vietnam, a seven-year-old named Juan Atkins was in a basement in the suburbs of Belleville, Michigan, getting his mind blown by his granny’s skills on a Hammond M3 organ. At 11, Atkins walked around the house in his father’s white motorcycle helmet (visor down) hoping to pursue a career in funk, an astronaut who wanted to grow up to be a starchild.

Atkins and Davis became friends in 1980 while taking electronics classes at Washtenaw Community College in Ann Arbor. “I had that strange feeling like I knew him from somewhere, though I never met him before,” says Atkins. “One of those people you know will have an impact on you.” Davis would introduce Atkins to films like Apocalypse Now (which famously embellished the CIA’s Urban Funk Campaign with “Flight of the Valkyries”) and John Carpenter’s The Thing (which, by the power of astro-parasitic yecch, violated mankind’s trust in arctic sled dogs). Their taste in music complemented each other: Atkins, the teenaged Parliament nut, and Davis, the only black Vietnam vet in Detroit going into record stores in his mirrored sunglasses asking for Tangerine Dream and Morton Subotnick. Upon returning home from the war, Davis immersed himself in Dells and Delphonics, lush Charles Stepney arrangements, and sweet soul for the pain and alienation. After that, it was all brain salad surgery.

Atkins remembers first walking into Davis’ house and feeling like he was entering a spaceship. “It was during the day, but it was dark — the blinds were closed. The only lights you could see were coming from the keyboards. It wasn’t really consumer gear — the stuff you could see anywhere. They had these LEDs. It looked like an airplane cockpit.”

Davis had purchased an Arp Axxe after watching Dario Argento’s Italo horror classic Suspiria, realizing this synthesizer could take him from a German ballet school run by witches to a substrata of natural gas existing on the ocean floor. Before meeting Atkins, he had released his first undanceable single, “Methane Sea,” named after an alternate fuel source which could also increase global melt and raise drexciya levels. The song was an electronic spanking of water babies of sorts. Davis calls it “new age psychedelic-trip music inspired by the end of the world, Jim Jones, clouds of flies, and seas of bloody corpses.” In short, the evening news.

This weird 45 managed to ooze onto the radio every night as the preamble to Charles Johnson’s show on Detroit’s WGPR. Mr. Johnson was the most fluid of boarders when taking to the air as Electrifyin’ Mojo, known to play the B-52’s, Prince, and Kraftwerk amid Funkadelic all-nighters. Listeners would herald each broadcast of Mojo’s Midnight Funk Association by flickering porch lights and blaring car horns. In 1981, Mojo reciprocated by playing “Cosmic Cars,” an automotive escape recorded in Davis’ walk-in closet in Ypsilanti, Michigan. To a pair of bloodshot studio eyes, streetlights blurred into stars during those late-night drives home. At the time, Davis drove a black-and-yellow Plymouth Horizon and listened to Goblin. Atkins bumped “Cosmic Slop” in a white Cutlass Supreme with gold interior.

//www.youtube.com/embed/aOBUqCIXXWY

“‘Cosmic Cars’ was the beginning of driving for me,” says Kevin Saunderson, who DJ’d parties with Atkins as part of the collective Deep Space. Saunderson was borrowing his mom’s Seville at the time. “It was music for progressive black kids, who came from the lower class but dressed like middle-class preppy kids, smoking sherm cigarettes, wearing Polo sweaters, khaki pants and penny loafers.”

Cybotron were just two guys pushing Korgs through a city that lived and died, and died again, by the machine, and somehow ended up on the same label as Creedance Clearwater Revival and Two Tons O’ Fun. Atkins, the future of Detroit techno, and Davis, his soul on Eldritch, rumored to be unbeatable at throwing darts underhanded. Inspired by the neologisms of Alvin Toffler, the duo was a hybrid of a particle accelerator and the type of robot that puts humans out of work, if not out of business altogether. On the label, in parentheses, Atkins’ partner is identified as 3070, a value that Davis assumed from Zoharian mysticism, a number of names. (Atkins would call his next project Model 500 to “repudiate ethnic designation.”)

“Cosmic Cars” was released on Deep Space Records, a label initially funded by “500 smackers” from 3070’s VA benefits. (They’d already recorded a track called “Cosmic Raindance,” for the hood of one’s cosmic Oldsmobile.) Cybotron’s first release on their own label, “Alleys of Your Mind,” would prove to be a handy excuse for Derrick May to meet his radio hero, Electrifyin’ Mojo. Late one night, after the Midnight Funk Association had convened, May waited for Mojo in a deli in Detroit and passed him a cassette of the Cybotron demo. It was some half-past-three in the morning, and you’ve got “Alleys of Your Mind,” a sandwich, and Mojo, an ex-Vietnam radioman who once identified himself as a figment of the imagination.

Deep Space 001 spoke more to early-model Ultravox and Kraftwerk than funk and disco. (“We were not Kraftwerk,” says Davis. “Kraftwerk had deep pockets.”) Minimal Third Wave, cyberpunk — whatever the assignation, Atkins can’t help but slip into Dead or Alive’s “You Spin Me Round” when performing it live. I recently heard “Alleys” at a wedding, celebrating the future of two people finishing each other’s thoughts. A friend told me that his beater copy of the 45 always got stuck on the redactive line, “Don’t tell what you see,” repeating itself for the unforeseen future, while the rest of the world moved on.

//www.youtube.com/embed/tbieq_x7zuI

To Rik Davis, “Alleys of Your Mind” was urban renewal. Go cry barren land. Ask where the song came from and he’d say nothing, in the most foregone sense. “There is not a brick left standing where I grew up. The neighborhood is gone, the schools are gone. My childhood no longer exists. You ever see that 1953 version of War of the Worlds with Gene Barry? When the general tells him, ‘Nothing remains.’ I grew up in those alleys, that post-industrial wasteland. That deurbanization.” While “Alleys” was yet another way into what Mojo called the “mental machine,” it could also be the soundtrack to Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, set in a midwest metropocalypse, often believed to be an analogue to 1960’s Detroit. “Detroit was one of the first cities to see how the technology affected the lives of working people,” says Atkins. “A lot of artists and musicians here were affected by the change.”

The third Cybotron single, “Clear,” intended to transform desolation into promise. But to Davis, it was Lovecraft’s Old Ones depopulating Earth, if the Rapture didn’t beat them to it. In 1982, “Clear” was far too busy filling skate rinks, too busy melting the wheels off your shoes — too busy being proto — to worry about who left open the last gate to hell. “Tomorrow is a brand-new day” never held such cheerless menace, but kids in Detroit, the Sons of the P, danced out of their constriction.

Juan Atkins remembers “Clear” as being misread as Scientology propaganda, auditing the reactive subconscious for an L. Ron Hubbard time-share. To Davis, the song could be face-down in the mud in Vietnam. “Clear” was carpet-bombing, a new Motor City interstate and Lovecraftwerk, a secret history of destruction buried in a song that greenly believed, “Earth is ours for us to save” — like a mothership on methane — though the Old Ones already owned the property. “Embrace the world-destroyer,” says Davis. “It’s the only way to live. Because whatever you cling to, it’ll be destroyed. The hippies perished in it. They thought it was forever. When you go away into something like that [Vietnam] and come back, you find that everything has been destroyed. Your youth is gone. There’s no place for you. Everybody has moved on. The pain is terrific. Nobody wanted to be bothered with us. When you come back, you’re out of style.”

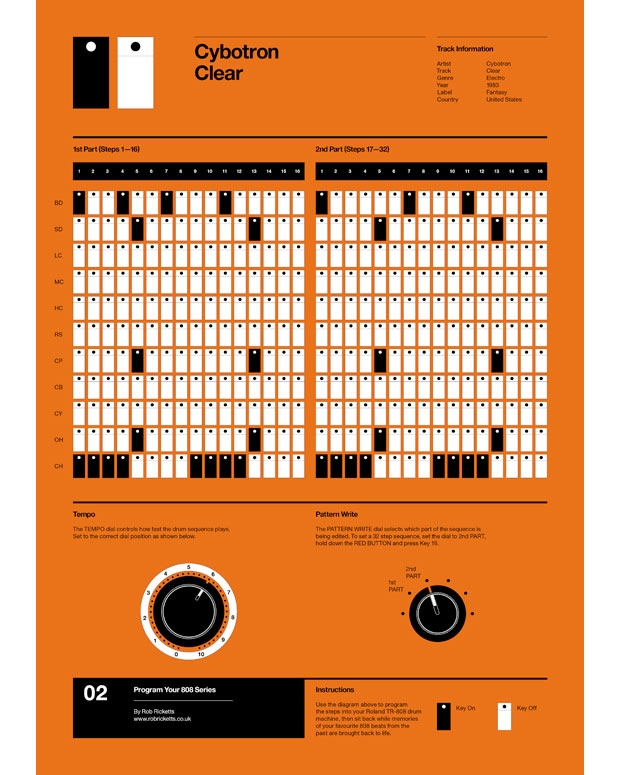

For Atkins, “Clear” was technocratic optimism, putting machines to work for him. The two voices — exchanged in pitches as disparate as the group’s conflicting visions — were created by what Atkins calls “slap-back delay with a comb.” Atkins would tell the Bay Guardian that he was using primitive speech software in the Commodore 64. “The delivery was due to the software. Even the choice of words to a certain degree is predicated on how well you can work the software.” The words were also haunted by an unintended irony: Would machines replace human assembly lines, so GM could chew up the highways that had already destroyed black neighborhoods? “Clear” ended on a positive note that nobody heard: “Out with the old / In with the new.” “They deleted it from the radio version,” says Atkins. “That was basically the concept behind the whole album. Clear out the old program. Technological revolution.”

//www.youtube.com/embed/fGqiBFqWCTU

For me, the technological revolution started in a Zenith clock radio with fake teak finish, inherited from my parents’ divorce. “Clear” was the first electro song I heard, an escape from junior-high psy-ops. My mother was in the room when it happened, fooling with a dislocated window shade, the sunlight crushed by October, Les Norman, the Night-Time Master Blaster of WPEG, on the radio. “Clear” came from nowhere, swooping from above. I didn’t know whether to nod my head, duck, or just blow up the request line. (Blowing up request lines was not easy before the invention of redial.) “That’s the idea,” says Davis. “It’s all coming down from above. It’s outside what exists.” What I saw outside that day was a swirl of dead leaves chasing each other in the street like children, as if something had just taken off. The song ends in a turbine swoosh, leaving you behind. White flight, black flight, from a city that ran itself into the ground.

“Nobody can tell you what happens at the end of ‘Clear,’ says Davis. “Put three or four people in the room and everyone has a different opinion of what they heard.” “Clear” could be Detroit then and now, minus the ruin fetish, urban gardening, and four Danny Brown albums. (“Detroit’s always been bankrupt,” says Atkins. “Ain’t nothin’ new about that.”) Nobody seemed to know what “Clear” meant, other than that abandoned factories made good party spaces — hosted by social clubs with names like Shari Vari and Lipstick — and that the song fit nicely between Kraftwerk and Debbie Deb, between clean Teutonic automation and debauched Miami strip malls. Though designated as the birth of Detroit techno, “Clear” couldn’t wait to get down to South Florida, where the song was adopted and sainted, a reason for DJs to shout out the clarity of bass sub-frequencies before blowing their woofers out to sea. The lyrics, “Clear, you’re behind,” were perverted to make room for that bottom. And so Miami backed into the future through a garrison of speakers, in the gear with the rear.

To the generation that discovers these conspiracies on the Internet, “Clear” would be recognized for what it isn’t, something Missy Elliot sampled in 2002 for “Lose Control.” The conceit was simple: Music makes you hallucinate blue Lamborghinis airbrushed by a Ciara chorus. It’s all seizures and tracksuits, boneless and acrylic. “Lose Control” enabled Rik Davis to drive off in a black Corvette C6, paid with sampling dividends, and to be pictured on his old MySpace page along with a photo of Missy in designer combat fatigues. Yet talking to Davis, you immediately sense that “Clear” was everything but the club. It was someone trying to make room inside his head. “‘Clear’ has a military value,” he says. Securing an area of operation could mean slaughtering the village. “Clear our displays,” their actions. Clear is classified, redacted. The human blank. A contradiction that would never admit as much. In itself, a white sky mindfuck.

Juan Atkins says Davis’ decision to go to Vietnam was the worst mistake of his life. But the motive for enlisting had less to do with godless Communist aggression than it did with just getting out of Detroit, a city that nearly burned to the ground in the riots of 1967. Davis, then 16, witnessed it from the gutted grocery store where he worked. Detroit underwent slum clearance in the Fifties, a policy of racism and deindustrialization that leveled and displaced entire communities that once thrived from wartime industry. By the ’60s, when Davis was catching every Roger Corman film in town, Interstate 75 had ploughed through his east side neighborhood, Black Bottom. “The population was cleared out, for a highway.”

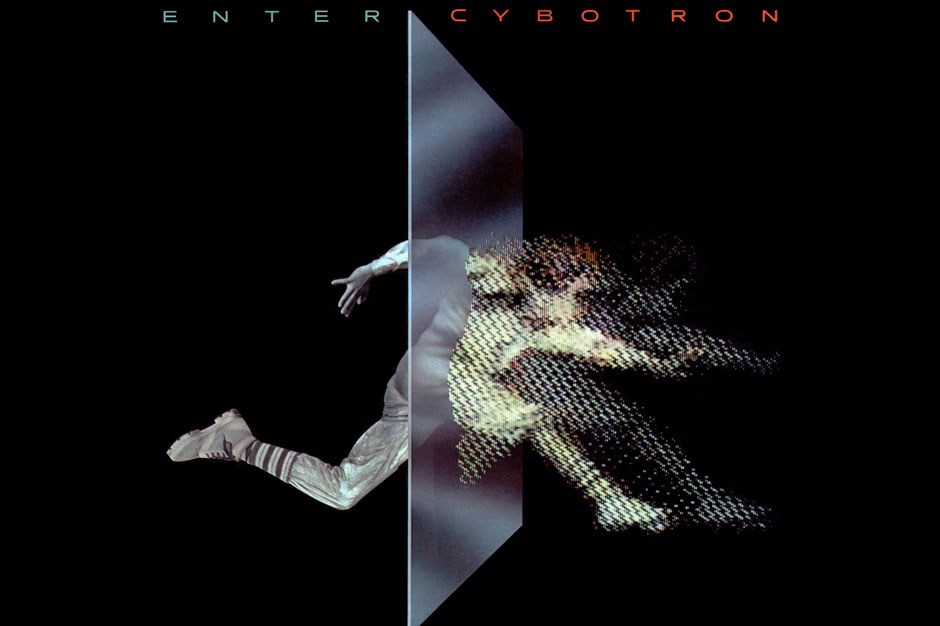

The cover of Enter could be Rik Davis on the run, passing from the human plane into pixelated noise, going binary in his tube socks. He was one of those kids who ran to the library to avoid getting mugged, passing his favorite theaters where he once saw the Temptations and the Miracles, chasing down the latest issue of The Purple Claw. Often he’d find refuge in a fanzine called Famous Monsters of Filmland, stuck on a space suit advertised in the back pages for $7.95. Davis felt a kinship with Ray Harryhausen’s 1958 stop-motion epic 7th Voyage of Sinbad, because he and the actor who played Sinbad shared first names. “You’re not going to believe this, but I joined the Marines to sail the Seven Seas with Captain Sinbad. Adventure and thrills.”

During grunt training at Camp Pendleton in San Diego, Davis went AWOL but turned himself in after learning of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination on April 4, 1968. The 18-year old was then shipped to Vietnam without his Dunwich Horror, though the Marines did provide a bible — all the same for Lovecraft and Cybotron. Revelations would become “R-9,” a Cybotron single about being trapped in the Good Word. Gloomier than “Clear,” and too tractor-beam meteoric for God, the 12-inch was released in 1985. “Human life does not depart from the word,” says Davis. “So you’re forced to step in synchronization, whether you believe it, whether you want it. Irrelevant. You’re programmed to fulfill it.”

On Cybotron’s “El Salvador,” Davis would use an Arp Axxe and a Korg vocoder to get from Vietnam to a Reagan-backed junta in Central America. Filtering noise through a modulated wave, he created machine-gun patter and helicopter drumming, sampled from combat memory in the 17th Parallel and mixed down in his nightmares. The lyrics quaver like algae’s grandmother, sub-tarn and only understood by Davis himself, who was then processing some post-traumatic demons through the vocoder. When I ask for a translation, he replied, “I don’t want to kill you but I have to.” The hook was just following orders, under extreme duress. “El Salvador” was not chosen as a single. With a sluggish zombie pulse, the song can’t get out of its own head much less to the dance floor. “I didn’t want to be a DJ,” says Davis.

Atkins and Davis’ paths have significantly diverged since splitting in 1985. While Atkins travels the world DJing and performing Cybotron songs with his Model 500 band, Davis works on his own music and occasionally materializes in Lovecraft chat rooms, counseling Guillermo del Toro on how to save his embattled film-adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness, a story whose main environmental concern was arctic monster thaw. (“I told him he was essentially pitching a cosmic slave revolt to a bunch of Satanists.”) I would definitely sleep better knowing that one of the guys from Cybotron had a small hand (or tentacle) in the realization of Mr. del Toro’s dream of directing Mr. Lovecraft’s nightmare for the metroplex screen.

In 2011, Model 500 played in an abandoned theater in Nowa Huta, a former Stalinized worker’s city outside Krakow. That night, “Clear” and its machines echoed through a space that had been industrialized for a future that never arrived. For Rik Davis — who would be deployed even further north to fight the Pathet Lao insurgency — the song’s line, Clear your mind, could’ve been wishful thinking. “I can’t swear to you that Ricky Davis ever actually came back out of the jungle,” he says. “We did ops that don’t exist. Ops that weren’t allowed to exist.”

At the end of Enter, somewhere in the darkness between “El Salvador” and “Clear,” you hear crickets chirping, perhaps wondering if anyone out there was tuned in. This would be Cybotron’s only field recording, a decision to drop a mic out the back door and see what a Detroit evening had to offer in 1982. A dim flicker of porch lights, maybe a faint car horn, the only sound still working on cinder blocks. Stridulation would be the way out of “El Salvador” and into being outside what exists. The helicopter and machine guns have faded into cries of “dear mother of God” in Spanish. You’re left alone with the ghost of your nonexistent ops and some bug-wing friction, before everything disappears. It’s kind of pleasant. There’s nobody else out there.

Special thanks to Michael Krimper for his interview with Juan Atkins that appeared in the San Francisco Bay Guardian.