Imagine your favorite song; now ask yourself why it’s your favorite. Some reasons are quantifiable — the musical key, the genre, the tempo, the release date, the instrumentation, and anything else you can train a computer to measure — and others aren’t, such as what you were doing the first (or last) time you heard it. You also “discovered” that song, somehow — via the radio, via a blog, via friends and loved ones — and shared that discovery with friends and loved ones in turn. Let’s call this whole shebang your experience of music, the process responsible for the emotional connection to this thing you love and cherish.

Now guess what? That emotional connection — it’s missing! You’ve lost it! Whether you’ve been buying or streaming tracks, hitting YouTube, downloading free stuff from blogs, or just plain stealing — you’re basically a zombie and don’t even know it, mindlessly consuming music you don’t really care about and aren’t really connecting with, and it’s the Internet‘s fault, man – all those spreadsheets and algorithms. But don’t worry, the Internet is going to fix that thing it broke. It’s going to make your musical self whole again, for just $10 a month.

Now, do you believe me when I tell you these things? What if I was the guy who produced Damn the Torpedoes?

The above only-slightly-paraphrased little pitch is what super-producer and music-biz veteran Jimmy Iovine is counting on: that his ability to straddle the distant worlds of creative artists and media moguls will imbue his latest venture, Beats Music — the streaming service he founded with Dr. Dre, featuring Trent Reznor as Chief Creative Officer, Topspin founder/former Beastie Boys web guru Ian Rogers as CEO, along with Beats Electronics President/COO Luke Wood — with a credibility heretofore unseen in the world of digital music, which remains a veritable Davy Jones’ Locker of capsized gimmicks and schemes.

Also Read

WHY SO MANY MUSIC TECH DEALS FAIL

But here’s the thing: It’s probably going to work. Because whether you’re the cool kid who’s turned off by marketing bluster and attempts at authenticity or you’re simply a housewife in Colorado whose Jackson Browne LPs are entombed in an attic somewhere, Beats is, finally, the service for you. It’s not without its faults, and it’s certainly not the first service to attempt most of what it claims makes it unique, but it is the first to combine everything that came before it into a total package that’s compelling, contemporary, and sexy. After all, these guys are record producers — and as Beats’ success proves, they’re also masterful personal-brand managers. This is, and always has been, their job.

At this very moment, there are roughly eleventy-billion digital-music concerns slugging it out to determine which two or three or four will control how the entire world consumes music — and hopefully other forms of media — for the next decade or so. There are: subscription services like Spotify, Rdio, Deezer, and Rhapsody (where, full disclosure, I oversaw editorial for seven years, up until last fall); established radio services like XM, Pandora, and Slacker; and then the big boys like Apple, Google, Sony, Samsung, Amazon, and Microsoft, with their various music strategies threaded through their larger corporate strategies. So Apple and Microsoft use music as a hook to sell devices, Amazon likely will use it to get you to buy more (physical) stuff, and Google is undoubtedly using it for vastly more nefarious purposes that only Dave Eggers can comprehend.

On top of that, there’s a glut of digital widgets and doo-dads, many of them insta-playlist apps, one of the most popular being Songza, which nailed the music for what you’re doing right now concept, with a fill-in-the-personalized-blanks style that everyone, including Beats, has rushed to copy and squash: “It’s [Monday evening]: Play music for [spending time with your kids],” etc. Furthermore, there’s an entire ecosystem of B2B (business-to-business, sorry) companies that sell technologies — reviews, recommendations, more playlist-generating algorithms — that power the features of many of the above services, three such favorites being Gracenote, the Echo Nest, and Rovi, music think-tanks so deeply woven into the fabric of digital-music consumption that they’ve suggested music to you, even if you’ve never noticed (trust me).

Now you’d think all this competition would be scary, and it is, but it’s also very good news for Beats. Having evolved in the primordial soup of the ’00s, digital music is now a fully fledged ecosystem, and Beats has innumerable shoulders on which to stand: At least theoretically, they’ve improved upon Songza’s playlisting concept; they’ve improved upon Rhapsody’s (and other’s) use of “experts” to hand-curate music in the form of playlists, recommendations, and blog posts; they’ve no doubt taken cues from Spotify’s crowd-sourcing, social, and artist-follow features; they’re licensing data from Gracenote and Rovi.

All of which is to say that Beats is not exactly new, and not exactly novel. But it does boast an incredibly passionate, incredibly seasoned, and incredibly business-savvy team of industry lifers skilled at making their ideas feel like sui generis revelations. And what they’ve built is the best, most fully formed music service extant, which is a feat in and of itself, and combined with Beats’ marketing agenda should be enough to make everyone from Spotify to Apple very, very worried.

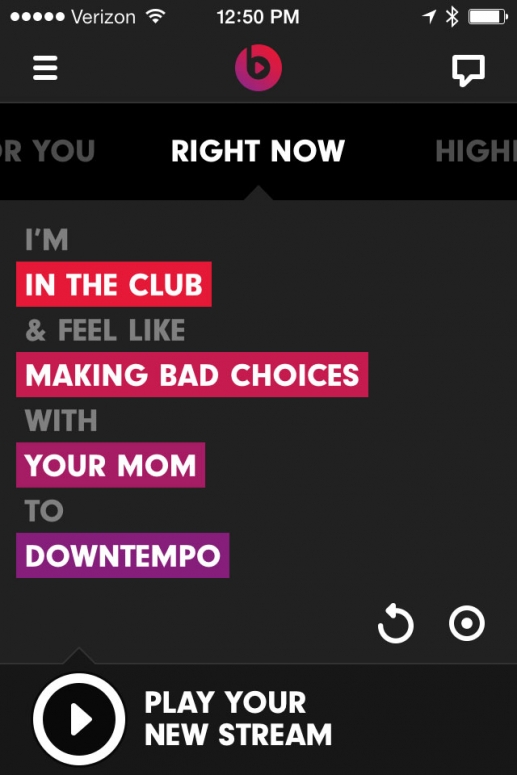

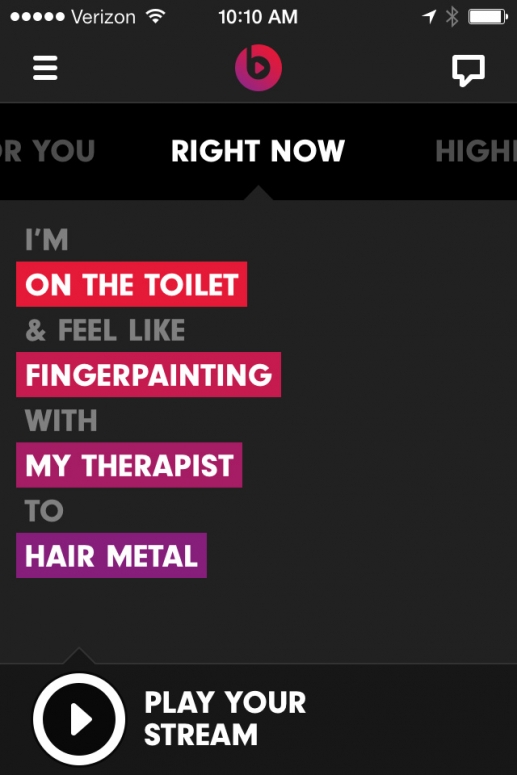

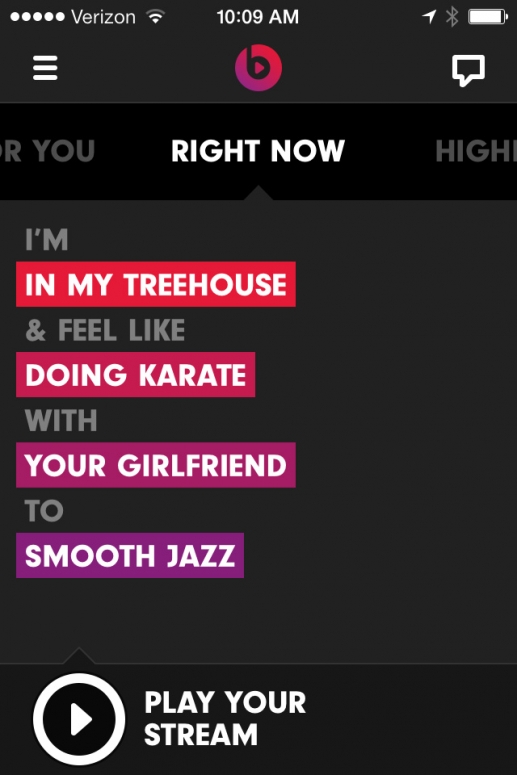

The basic premise of Beats is that it knows who you are, and it knows what you like, and its team of curator elves is working around the clock to hand-deliver music to you. As you consume that music, liking it or disliking it, the system learns more about your tastes and preferences, and presumably delivers better recommendations. The feature that most exemplifies this promise is a Trent Reznor brainchild called “Right Now,” a.k.a. the Sentence, a music-oriented Mad Lib wherein you describe where you are, how you’re feeling, who you’re with, and finally, what music you want to hear. As in, “I’m AT HOME and feel like COOKING with MY PETS to AMERICANA,” which happens to be where I was and what I was doing on a recent Saturday.

While the playlist that combination generated was certainly within the bounds of Beats’ broad definition of the genre (“The borders of Americana are wide open, so long as the artists find some unique way to connect with the country’s rich musical traditions”), it dwelled heavily in the late ’70s and early ’80s, didn’t feature a single Ryan Adams/Jayhawks/Steve Earle song (that’s not a requirement, but still), and in fact didn’t play a single female artist until I changed “MY PETS” to “MY INNER GODDESS,” with whom I shouldn’t be required to spend time in order to hear an Emmylou Harris track.

I spent an entire weekend with Right Now, and the best I can say is that it’s hit-and-miss in an entertaining way: Despite the handful of permutations of “Indie” I tried, I couldn’t get it to play anything more contemporary than three or four years ago (though “Dum Dum” by Idaho was a pleasant surprise). On certain playlists, the same artist would repeat too frequently, and in one case I got both the live and studio versions of John Hiatt’s “Real Fine Love,” one after the other. The biggest, most quizzical boner was when I set Right Now to “AT HOME ROMANCING with MY PETS to DOWNTEMPO,” and 3 Doors Down’s “Here Without You” came on.

Which, okay, fine: Not only is this stuff hard, but Beats doesn’t yet have the glut of user data it will eventually crunch to make this feature better — and even when they do, it’s not a lock. Pandora’s wizards (who were the first to really market their human curators via the mysterious “Music Genome Project,” a term that conjured images of beakers and lab coats and Willie Nelson songs) have been at this for a decade, and they’re still far from perfect; meanwhile, even now, Apple, with its near-infinite resources, continues to scrub the Christmas music from its iRadio feature. Auto-playlisting is far easier to market than to execute — hence Songza, and hence Beats’ Right Now, what with its reliance on the power of suggestion to convince users of its accuracy, because is there really a sub-genre of Americana that’s only appropriate for when you’re hanging with “Zombies”? I doubt it, and that probably explains why my playlist didn’t vary much when I futzed with any of the variables besides, you know, “Americana.”

In the industry, we tended not to talk about promoting or featuring music, but rather merchandising it, and in that sense Beats is using a very heavy hand in both its product and its promotions. Maybe that turns you off, and maybe it doesn’t. Regardless, the rest of the service is spectacular; in many instances, it improves upon the best features from its competitors: offline playback (download stuff to play off your phone on airplanes and such); the ability to “follow” artists and users; thousands of hand-programmed playlists, and the ability to browse them by genre, activity, and “curator,” e.g. you can flip through playlists made by Pitchfork, Downbeat, Rap Radar, etc.; and a sleek overall package that, perhaps most significantly, was designed for mobile first, meaning you’re not getting a bunch of website or desktop features clumsily crammed into a lousy mobile app.

Because it was designed for mobile from the ground up (and as any executive will tell you, mobile is where the streaming battle will be won, or more likely lost), Beats is far and away the most elegant and compelling streaming app on the market, a pole position it can expect to enjoy for something like three to nine months, before, in the grand tradition of the music business, its best ideas are stolen and repurposed by its competitors.

Meanwhile, though its overall product design and loudly trumpeted artistic credibility are what’s justifiably drawing so much attention to Beats, the lynchpin to its success is the absolutely shocking array of blue-chip marketing deals it’s secured, deals so canny and impactful it makes the service’s impending Super Bowl ad seem like a sandwich board in Times Square. First, there’s Ellen DeGeneres, who will be dutifully promoting the service on her show to her devoted audience of mostly technophobic women, the same people who routinely send Susan Boyle to No. 1 via CD sales alone. (And speaking of CDs, Beats has a deal with Target, which means that Dr. Dre’s music service will now compete with Ms. Boyle’s little plastic coaster for the average Target shopper’s buck.)

But most importantly, there’s AT&T, which will bundle Beats with its service: $10 for a single subscription, $15 for a family pack of five; the latter deal point — and again, just trust me — is on par with Edmund Hillary’s summiting of Everest, in terms of how long and how intensely the streaming industry has coveted it. Beats may prosper based on that agreement alone.

So they killed it with their product, and killed it with their marketing. There’s a third leg to this stool, though, one familiar to anyone who’s followed the debate over subscription streaming in the last year: Is Beats good for artists, i.e., will its business model and the amount it pays for content create or at least contribute to an economic climate that feels fair and doesn’t piss off Thom Yorke? Maybe. Beats claims it pays the same rates to rights holders as everyone else, which means it’s making the same argument everyone else is making: Until we can attract enough users to replace all the revenue that the music business has lost from everybody stealing its shit, the business — i.e., the labels — will continue to take their huge cuts, with the rest trickling down to artists based on whatever quaint arrangement artists have made with the labels, not with the services.

It’s worth noting, though, that Beats, like Rhapsody, is not offering a free version of its service, which means that unlike Spotify, its paying users aren’t subsidizing the cost of giving all that music away for free. Ian Rogers — who, from his Beasties experience to his founding of Topspin and running of Yahoo! Music all the way down to his skateboarding prowess, has earned a level of credibility among musicians that’s practically bulletproof — told me that one of the first things he insisted on at Beats was that indie labels get paid the same as majors, which is the kind of policy that would get you fired pretty much anywhere, let alone at a music service. And so Beats’ argument with regard to artist payments resembles its larger positioning of the service as a whole: Our heart is in the right place, and trust that our money will make it there soon.

Here’s a question neither I nor Mr. Jimmy Iovine know the answer to: Do you trust Beats, or any of these services, to recommend music to you? Does the trust you have in “curation” approximate or even slightly approach the trust you place in friends, loved ones, or even for that matter the now-largely-extinct record store nerd, that quotidian human who, when you asked about something, could talk back to you, could listen to the nuances of your speech and witness your body language, combining all that with his or her knowledge of your tastes to recommend something truly tailored for you, and/or to insult you?

The answer to this question will play a large role not just in whether Beats succeeds, but how the industry evolves from this point forward. Beats represents the biggest bet anyone has placed — if only in marketing dollars alone — on the value of human music experts to a music service designed for humans, which up until now has largely been regarded as a novelty by an industry driven, like all industries, by scalability and low overhead. If Beats succeeds, it will change the way all of us who experience digital music experience digital music, and the extent to whether that change will be for the better will depend on whether you were ready for it to change at all.

There are at least two charming future anachronisms in Spike Jonze’s haunting man-and-his-operating-system love story, Her. First, as folks on the Internet already have pointed out, Joaquin Phoenix’s character calls it “Internet porn,” as if in the future there’ll be any other kind; and second, near the beginning of the film, during Phoenix’s commute home, he asks his OS to play a melancholy song. This is not quite right, you see, for in the future — in a Beats future, at least — the OS won’t require so much as an adjective’s worth of input. In the future, it’ll understand your myriad musical preferences, all those component parts of all the music you love. It will know where you are and what time it is, what current events took place that day, and which of those you’re aware of. It’ll know the weather, your relationship status, everything you’ve ever purchased. You won’t have to say, “Play a melancholy song” — you’ll just have to say, “Play music,” and the right song for that moment will play.

Maybe it’ll be 3 Doors Down. And maybe not.