“It’s like a game of Whac-A-Mole.”

DULLES, VA — Inside a typical-looking suburban business park in Dulles, Virginia, sits a spanking-new 3,200-square-foot building. It has no signs, a fortified fence, and a lot of security cameras. Each morning, hundreds of employees outfitted in business-casual attire, with their laminated ID badges hanging around their necks, stream inside the cool gray structure for one purpose: to outmaneuver heavy-duty drug cooks and manufacturers.

Arthur Berrier, a bespectacled man in his late 50s, with a likable nerdy demeanor and clear passion for organic chemistry, leads a key group of these shock troops in the new war on synthetic drugs. A senior research chemist, Berrier is in charge of a 46-member team — called the Emerging Trends Lab — that works within the DEA’s Office of Forensic Sciences.

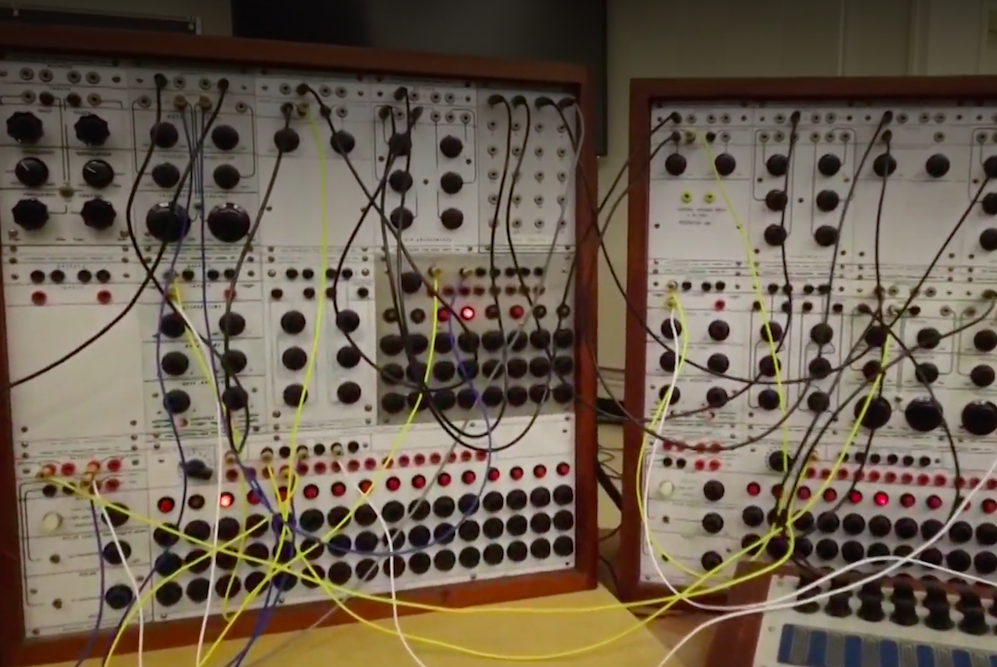

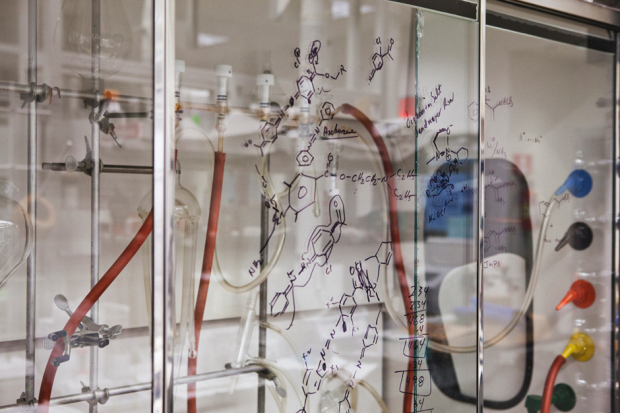

The challenge faced by Berrier’s chemists is more complicated than Bolivian coca leaves or Middle Eastern poppies. “Someone — the people who were making these illegal drugs at first — was simply reviewing some science literature and copying what was done,” Arthur says. “That part is still going on. But what we’ve found more perplexing is that they’ve also started coming up with their own compounds.” Unlike the DEA agents in the field, who don Kevlar vests and ski masks to bust drug rings, Berrier battles the growing synthetic-drug market by using fluorides, crystallizing acids, and countless rows of Erlenmeyer flasks filled with the toxic powders. Not only does the spotless, state-of-the-art lab run around-the-clock tests on seized evidence, but it also brews its own in-house synthetic drugs as an attempt to anticipate what’s coming next.

For the large-scale distribution of bath salts that’s currently taking place in the United States, one needs to know more than your average backyard tweaker. This is advanced-level chemistry. “What they’re doing is taking the molecules they’ve made and that they’ve read about and they’re putting different pieces together to form something totally new,” Berrier says. “And it makes it harder for us to do the analysis because it’s totally new.” In other words, synthetic drug organizations have guys like Berrier working for them, too. “I think, forensically, it’s a game of Whac-A-Mole,” says Jeffrey Scott, a former narcotics agent in the field who now works at DEA headquarters. “We can control these substances with a temporary ban, but we don’t control Purple Wave or Ivory Bliss. We control the components within them.”

When Scott was doing undercover streets busts, it was a little more straightforward. “Coke is coke and heroin is heroin. And it’s pretty easy to know what you’ve got. But now, when you go out and seize a warehouse full of something packaged as Dragonfly, you really have no idea what it is.”

If chemistry is one aspect of the problem, the Internet is another. Take, for instance, mephedrone: It was first synthesized under the name “toluyl-alpha-monomethylaminoethylcetone” in 1929 by a French pharmacologist named Saem de Burnaga Sanchez. It remained an obscure object of academic interest for 80 years until a clandestine chemist working under the pseudonym “Kinetic” uploaded a how-to guide on the Hive website. Then the drug exploded across Europe. The ban on mephedrone put an end to that specific synthesis, but chemistry, like any recipe, is malleable. “The Internet is great at proliferating this sort of information almost faster than law enforcement can really keep track of it,” says Robert J. Bell, a coordinator inside the DEA’s synthetic drug department.

Once the recipe makes its way online, anyone with the financial means can order chemicals in bulk, usually from China and Southeast Asia. The chemicals are most often synthesized here in the States, then packaged and distributed at both the wholesale and recreational level. The DEA has found that most websites selling bath salts wholesale have domains registered in the U.S. Hip to the current DEA ban, these sites will advertise their products as being legal in all 50 states and explicitly say they do not contain substances banned by the DEA.

It’s a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t scenario in terms of legislating synthetic drugs. If the law is specific and names chemicals outright, then manufacturers know which ingredients to avoid. Some states have passed their own version of the Federal Analog Act, which gives prosecutors the ability to try cases against those who traffic in substances that have a similar structure and effect on the human body as outlawed chemicals. But since there’s no clinical data on new substances, trying these cases against synthetic drug distributors has proven to be a Kafkaesque endeavor. “It’s a hard process,” says Bell. “It’s a big ship to turn.”

As of today, no wholesale distributors of bath salts have been brought to trial successfully.

This story originally appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of SPIN, which you can order here now.