The members of the Bad Brains first met each other at Central High School in the lower-income D.C. suburb of Capitol Heights, Maryland, where Earl and Dr. Know were in the same art and science classes. Earl and HR’s father was in the Air Force — HR was born in England — and the brothers moved from place to place as kids, but they finally settled in an apartment development near where Dr. Know and his friend Jenifer lived. Earl, Jenifer, and Dr. Know (a regular attendee of Frank Zappa and Yes concerts), had formed a progressive jazz band called Mind Power, but when their singer Sid McCray introduced them to punk, they refocused. After seeing the Ramones and Clash in concert, HR decided he wanted to try singing and eventually replaced McCray.

It was 1977, and the foursome were pushing for something new. “We decided to change our name from Mind Power to the Bad Brains after hearing the Ramones’ ‘Bad Brain,'” says HR, a “withdrawn” teenager who found solace as a member of his high-school diving team. “We had seen the Sex Pistols movie [1980’s The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle] and heard Never Mind the Bollocks, but we couldn’t really relate to the message. I thought it was a bit extreme. I wanted to offer something more positive.”

Their version of less extreme and more positive was a furiously kinetic explosion titled “Pay to Cum,” which they self-released as a single in 1980 and eventually re-recorded for 1982’s Bad Brains. Dr. Know can think back to someone telling him at the time that the song was technically speaking the fastest song ever released. HR remembers “telling Earl he should try to make [“Pay to Cum”] as groovy as possible but instead he ended up making it as fast as possible.” As a result, HR continues, “I delivered the lyrics with extra spirit, extra oomph and soulfulness.”

The content of those lyrics was more emotionally complex than, say, Black Flag’s nervous breakdowns and Discharge’s war tales. HR says his words are about “not allowing yourself to give up and being peaceful. I came to know with no dismay that in this world we all must pay — pay to write, pay to play, pay to cum, pay to fight.” Add to that almost-Buddhist, life-is-suffering worldview the fact that Bad Brains could actually play their instruments virtuosically — anathema to the punk spirit of the time — and you had a band operating on a previously unexplored plane.

“On one hand, they had a street-level appeal, but on the other they were also dedicated musos,” explains Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid, who once declared to SPIN that Bad Brains were the best band of the ’80s. “They weren’t just guys who picked up guitars and were flailing away at them. They were very tuneful. The Bad Brains had guitar solos, and they were musical, but it was not like Hendrix. It was like, ‘Don’t blink or you’ll miss it.’ They were apocalyptically passionate and created a field of energy that you were either pulled into or repulsed by. It was pulverizing music in that way.”

Pulverizing, but with a purpose. “I was talking to my dad one day, and he suggested I read a book called Think and Grow Rich, by Napoleon Hill,” HR elaborates. “In the book, one of the teachings was, ‘Anything the mind can conceive, the mind can achieve.’ And one of the principals was to be positive and have PMA: a ‘Positive Mental Attitude.'”

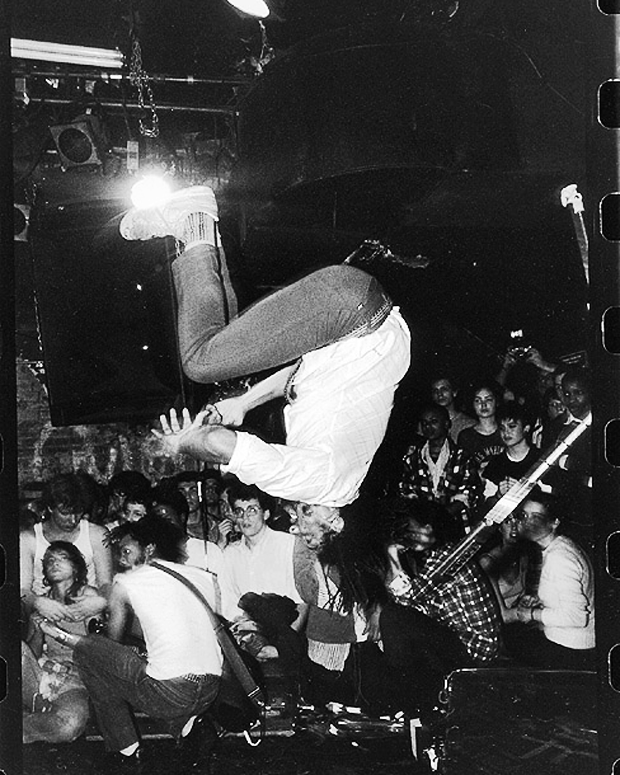

That phrase, PMA, would pop up in several Bad Brains songs, but first appeared in 1982’s “Attitude,” a giddy screecher that the band has often used as a concert opener. And HR, prone to pogoing and backflipping onstage, would similarly command his thrashing audiences to “mash it” while speaking in a faux-Jamaican patois. (The band members embraced Rastafarianism after seeing Bob Marley perform.) That phrase translated as “mosh it.”

Subculture-defining malapropisms aside, the group struggled to achieve consistency or financial success. In the early ’80s, HR was as erratic offstage as he was explosive onstage. There were jail stints and an alleged homophobic incident involving Biscuit, the gay singer for the punk band Big Boys (HR calls it a misunderstanding). In 1984, shortly after the band re-recorded many songs on the Bad Brains release with Cars frontman Ric Ocasek (for 1983’s Rock for Light), he and his brother left to work on a mostly reggae, critically maligned record called It’s About Luv. “We were still friends, still brethren,” HR says of the split. “We wanted to do different stuff, we tried experimental music.” When asked why he left the group just as it was gaining traction he says, opaquely, “for the experience.”