This is Part One of “Miles Style,” SPIN‘s two-part story on the life and legacy of Miles Davis. Part One originally appeared in the November 1985 issue of SPIN. (Check out Quincy Troupe’s other essay, as well as his contributions to the American Book Award-winning memoir, Miles: The Autobiography, here.)

“By me having a $60,000 yellow Ferrari, being black and living in a beachfront house in Malibu, the police have already stopped me three times,” Miles Davis is saying, in that famous hoarse whisper of his.

He bites down hard on his Danish, takes a long, deep drink from his Perrier bottle, and continues. “This happens all the time. They’re always saying they thought I was drunk, that I was weaving all over the place. This happens especially at night on the Pacific Coast Highway.”

“One time, my wife, Cicely, was asleep beside me in the car when they stopped me. When she woke up she heard them accusing me of being drunk. She told them I didn’t drink. But they don’t care about that. It’s just racist. But we black folks know about that. It happens every day to a black person. It happens here just like it happens in South Africa.”

“The police make me mad, and I never say the things they want to hear,” Miles says as he arches another line in one of the drawings he is constantly doing these days, which have graced the covers of several of his recent albums. “I don’t be saying, ‘Yessuh, boss,’ or ‘I’m takin’ the car to be washed and cleaned.’ Shit like that. Man, ’cause the shit I be wearin’ should tell any fool that I belong in the car! They ask me who I work for.”

“I mean, a cop who has to work every day really be mad when what I’m drivin’ costs more than what he makes in a whole year! You know what I mean? One cop, after askin’ me to pull over, says to me, ‘Didn’t you see me behind you?’ ‘Naw,’ I said. ‘I wasn’t looking behind me watchin’ you. You watchin’ me.’ I didn’t know he was behind me. I don’t care if he’s behind me. Fuck him!”

But the cops and Miles have been at odds more than once. He was arrested while sitting in his red Ferrari in a no-standing zone on Fifth Avenue in New York. The cop said he noticed that Miles’s car had no inspection sticker and asked him for his driver license. While Miles was looking for it a pair of brass knuckles fell out of his bag and he was arrested. Brass knuckles are illegal under the Sullivan Law.

Miles said he carried the knuckles for protection; he had recently been grazed by a bullet fired by an unknown assailant. Another time he was beaten by a New York City detective for refusing to move from in front of a club where he was playing.

“Policemen are weird,” Miles says, screwing his dark face into a painted and quizzical expression of almost disbelief. “They do weird shit. They’re like storm troopers. Shit, they even go to Germany on excursions to learn how to do more of the weird shit they do.”

These concerns led Miles to record You’re Under Arrest a few months ago, the closest thing to a pop record he’s ever done. But then Miles has always been on the cutting edge of change in American music, and much of the time he has been highly criticized as well as praised for it.

And now, as then, he doesn’t seem to be listening to the critics, many of whose voices are raised in loud protest over the direction of his new music, but goes his own way, paying attention only to what his band members, trusted friends, and other musicians whose judgement he respects have to say.

Under Arrest is a conceptual album, moving from a political statement musically to a concluding political musical statement. Included among these political concerns are Miles’s human and musical responses to sometimes oppressive political actions.

Thus, the pop ballads “Human Nature” and “Time After Time” from Michael Jackson‘s and Cyndi Lauper‘s latest albums are part of the musical fabric of Under Arrest. Both songs deal with love, touching, loneliness, and isolation. The album’s first composition, “One Phone Call / Street Scenes,” written by Miles, begins with the words, “You’re under arrest, You have the right to make one phone call or remain silent, so you better shut up.”

“See, on the song we’re supposed to be snortin’ coke. So I had my percussionist Steve Thornton say, ‘We just came from Miami and that’s our religion down there. We do this all the time, so you’d better shut up. ‘Cause it’s none of your business.'”

“I had some special, real handcuffs for the recording session. You can hear them clickin’ on ‘Street Scenes,’ and they really put those handcuffs on me!” He laughs at the memory. “I was interested in the recorded sounds of the handcuffs lockin’. I wanted that sound on the record because it happens to so many people all over the world.”

Under Arrest‘s concerns progress from being locked up for being part of a “Street Scene” to being locked up politically and being subjected to the looming horror of a nuclear holocaust. Listen to the synthesizer boiling up and simulating the howling, flaming winds created by the nuclear explosion on “Then There Were None.” Then listen to Miles’ sad, lonely, and haunting trumpet, the “5, 4, 3, 2…” countdown, a baby’s wailing cry, the tolling of bells, and Miles at the conclusion of the recording saying, “Ron, I meant for you to push the other button.”

Art as a mirror of society. The real world put down on vinyl as music. Miles, always on the cultural, musical, and artistic edge.

Miles comes from a politically conscious family. His late father, a prominent dentist and landowner in East St. Louis, Illinois, who once ran for public office, is from a long and distinguished line of Davises who were extremely proud of their heritage and didn’t take shit from anyone.

“My father was a big influence on me,” he says, pausing to think for a second, stroking his chin thoughtfully with his long, bony fingers, his normally fierce eyes softening for a moment at the memory of his father. “He taught me to choose what was important to me and not look back. Or care what anybody else thought.”

And Miles has done that—chosen what was important himself—for all of what is an amazingly creative and important musical career. His music and the groups he has led have changed jazz at least five times.

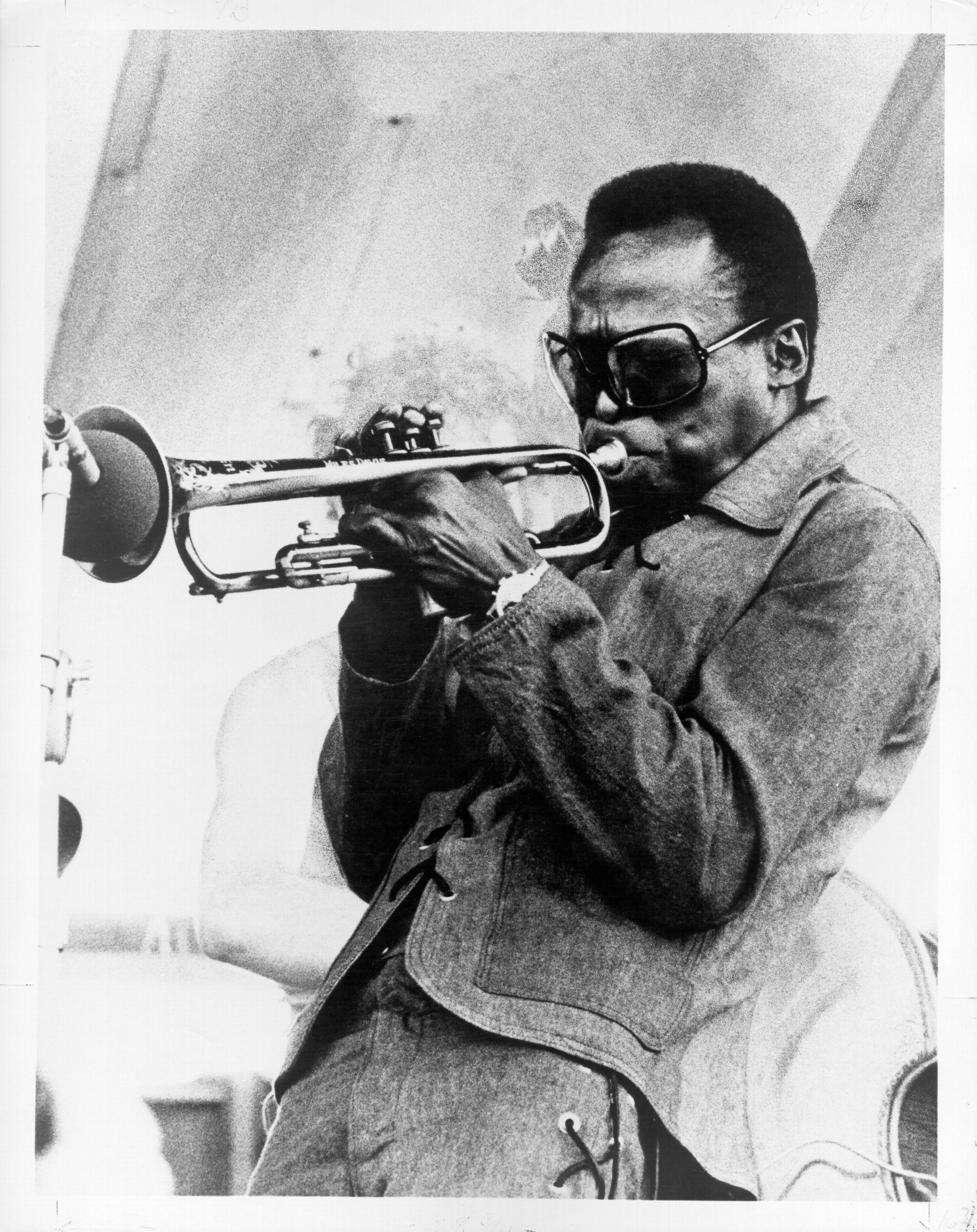

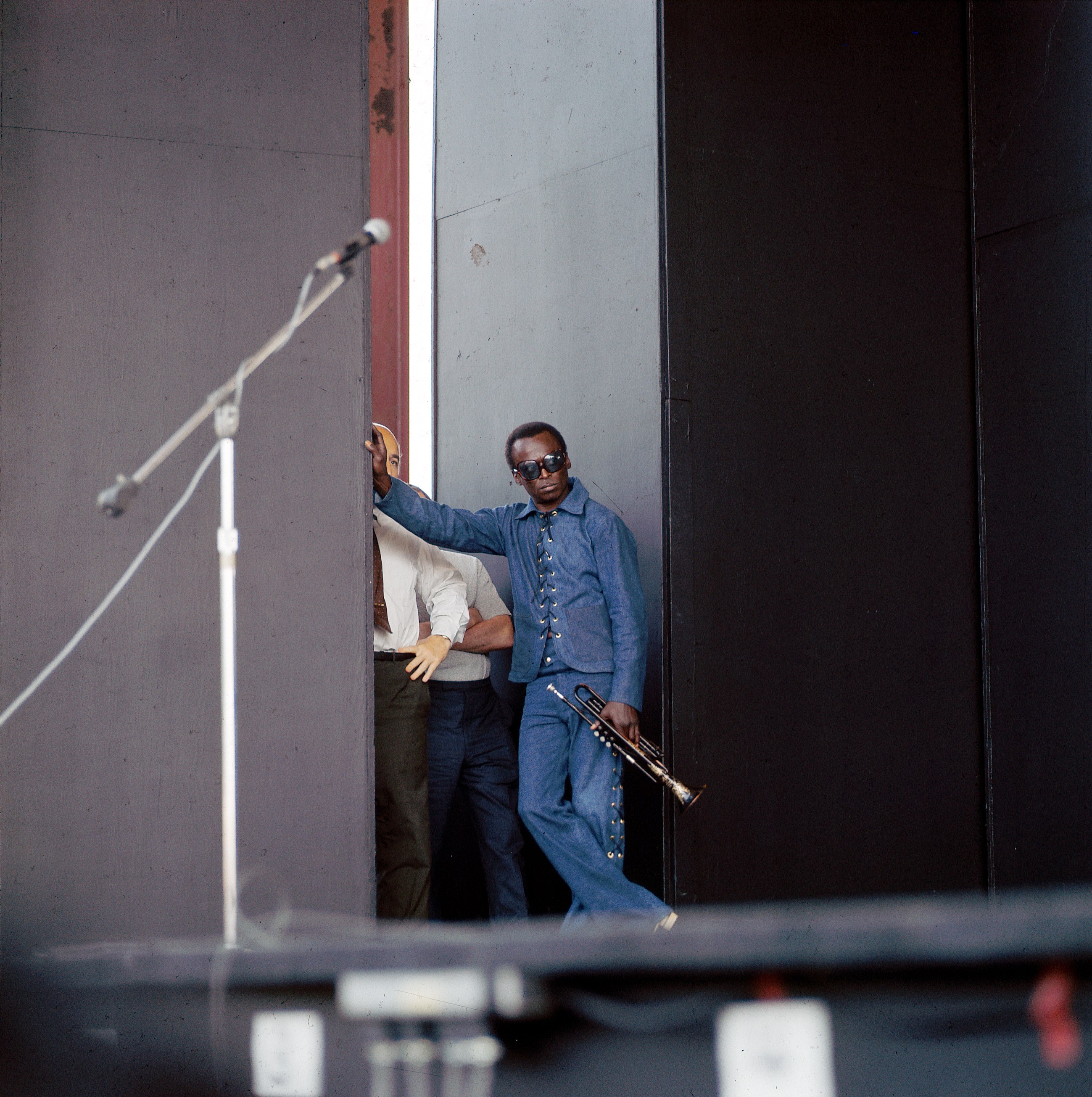

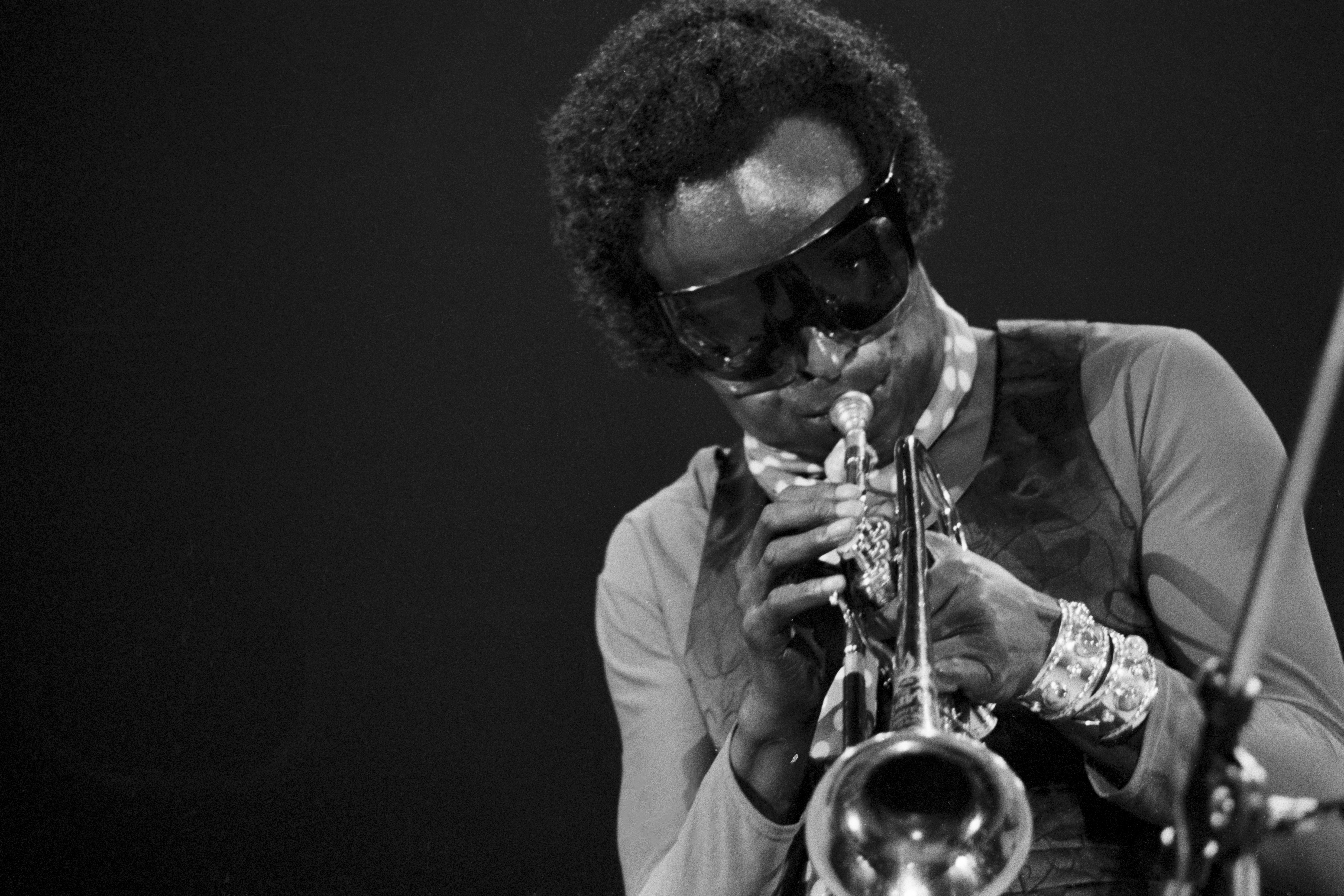

But his influence extends beyond music. He affects clothing styles, fashion, the way people speak, their attitudes toward themselves and the world, the way they stand, the way they hold a drink, everything. Some people go to his concerts not to listen to the music but to see what he has on, the way he’s standing that night on stage, the style in which he’s carrying himself.

According to George Butler, who was Miles’s executive producer at Columbia Records, the late Soviet head of state, Yuri Andropov, an ardent jazz fan and a fanatical admirer of Miles’s music, once sent his personal limousine to chauffeur Miles around Poland when he was playing a series of concerts there. Andropov was the non his death bed and too sick to attend. But rumor had it that had he been well he would have been there.

Miles’s grandfather, Miles Dewey Davis the first, was a successful bookkeeper and landowner in Arkansas in the late 19th century. He was said to be so good at bookkeeping that local whites came to him clandestinely to balance their books. Later, around the turn of the century, he was driven from his land by whites who grew jealous of such a smart and enterprising black man.

Miles’s father was wealthy, by black standards of the day. He had a city home and a country farm 20 miles outside of East St. Louis where he raised prize-winning pigs and where young Miles could retreat to hunt, fish, and ride horses, a passion that remains with him today.

Miles’s father was a “race man” who favored Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement over the integrationist tendencies of the NAACP. These ideas were passed on to young Miles. Doc Davis once took a shotgun and went looking for a white man who had called young Miles a nigger (he couldn’t find him).

East St. Louis, like St. Louis across the river, was a very tough town. While St. Louis closed down after midnight and didn’t serve alcohol anywhere on Sundays, across the river, East St. Louis never closed. The clubs were wide open and gambling flourished.

Like New Orleans at the bottom of the Mississippi, St. Louis has always produced outstanding trumpet players. In both cities, riverboats ferried up and down the river, carrying outstanding musicians who made good livings playing for the passengers. Both cities have long traditions of brass marching bands and were home to some of the very top jazz trumpet players: Buddy Bolden, Louis Armstrong, Wynton Marsalis, and Terrence Blanchard, all from New Orleans, and Louis Metcalf, Levi Maddison, Harold Baker, Eddie Randall, Clark Terry, George Hudson, Davis, and Lester Bowie, all from St. Louis.

So when Miles’s father gave him a trumpet for his 13th birthday (his mother wanted to give him a violin; when this was rejected it was the cause of much friction between his parents), he was in a fertile area to grow musically on the instrument.

By his senior year in high school, Miles was already looking past East St. Louis and St. Louis. His teacher, Elwood Buchanan, had taught him to “play without any vibrato,” because he was going to “get old anyway and start shaking,” and to play “fast and light.”

He turned him on to Clark Terry, a friend and drinking buddy of his, and Harold Baker’s playing. Miles began sitting in with Terry down on the Mississippi with riverboat musicians from New Orleans and playing in jam sessions all over St. Louis. Then Terry, Miles’s idol, went into the Navy in 1942. Miles graduated from high school and joined the Billy Eckstine band at the Club Rivera in St. Louis. The band already included Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Art Blakey, who told Miles he should go to New York. Convincing his father to send him to the Juilliard School of Music, in 1945 Miles arrived in New York City.

Juilliard was only a cover for what Miles really wanted to do, which was become a part of the avant-garde music scene that was happening in and around Harlem and 52nd Street. He was also looking for Charlie Parker. Miles found “Bird” after a short while, and they became fast friends and roommates.

At 18, Miles had arrived. Soon, he was hanging out with Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Tadd Dameron, Thelonious Monk, J.J. Johnson, and Max Roach, among others. In 1947, Miles joined the Charlie Parker Quintet—the quintet of jazz—which included Max Roach on drums, Miles on trumpet, and Parker on alto sax. By this time, Miles had come under the influence of both Freddie Webster and Dizzy Gillespie. He was also developing his own voice—on the horn, based on the St. Louis style of playing—spare and blues-based, but fast, clean, open, lyrical, bold.

* * *

Bebop was a revolution. It came downtown from uptown New York. From Minton’s Playhouse, Lorraine’s, and Smalls Paradise in Harlem to the new midtown club of “The Street”—52nd Street. Parker, Kenny Clarke, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, and Gillespie experimented uptown, then brought the music downtown. Bebop was based in the small ensemble, with an emphasis on improvisation rooted in African rhythms and the blues.

It was a rebellion against the stiff swing arrangements of the 1940s and had a direct influence on clothing styles and language. The literary Beat movement came directly out of bebop, as did many of America’s top avant-garde actors and painters, such as Brando, James Dean, Montgomery Cliff, Jackson Pollock, and William de Kooning.

Max Roach, the legendary drummer, was then, like Miles, one of the many young, unknown musicians who were hanging around Harlem jazz clubs trying to find a place in the new music. “We both worked with Charlie Parker’s band and were roommates on the road,” Max says. “We were staying up all night and all day, looking for jam sessions, some place to play. New York was different then. We could run the streets until we all crashed. I mean, our main thrust was to be a part of the music scene. We had a little group of guys—Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Milt Jackson, Tadd Dameron, Bud Powell, J.J. Johnson, Thelonious Monk, Fats Navarro, and Miles—who were all about the same age, thought the same kind of thoughts.

“The thing I always enjoyed about playing with Miles,” Max remembers, “is that he always went his own way. It helped me to know that creativity was always out there. You see, Miles started playing differently back in those days. Every other trumpet player was so influenced by Dizzy—not that Miles wasn’t influenced by Diz. But Miles decided he was going to do something else.”

What he did, says Lester Bowie, is play “completely different from anybody else in his era. The way he plays his intervals, the way he plays through chord changes, that’s what made him really different. Everybody else played sort of the same, up and down, musical passages, chord changes, in intervals of seconds, thirds, fourths, fifths, and sixths. But Miles plays in between all of that. He plays sideways. He runs through whole tunes sideways.”

“It was really different from the way anybody else had ever approached the trumpet. It takes genius to come up with a different idea, a different way of doing something. Considering all the great trumpet players who had come before him, it took quite a bit for Miles to come up with a new and different approach. He was the innovator on the trumpet.”

And if Miles was beginning to have an impact on the music world with his playing, he was also beginning to influence musicians and others with his great sense of style.

“Miles was always real clean, even back then,” his high school friend Ralaigh McDonald recalls, “like most musicians. We all dressed up our hair, clothes, shoes, everything immaculate. This was our pride. When we waled on the stand, we wanted to be pretty. We wanted to act cool, be cool, play cool, play pretty, look pretty. So we all, Miles included, did that.”

“I used to go to the pawnshop back in the old days,” Miles muses when I ask him to define his style, “and buy a secondhand suit for $20. Then I’d take the vest and put a ticket pocket on it. And then guys would say, ‘Aw, man, you can do this shit because your old man’s a doctor.’ And I would say, ‘Fuck you. He ain’t buyin’ this shit I got on!’ My father was conservative. I had to buy him clothes, you know?”

“I used to watch guys, black musicians mostly, coming through St. Louis, I used to watch how they dressed, how they stood, how they held their horns. I could tell if a guy could play by the way he dressed, how he stood, and the way he held his horn. I mean, although I was influenced by the British style of dressin’, you know, Fred Astaire, he had a little flair that I liked, Carry Grant, Walter Pigeon, people who looked like they belonged in their clothes, I always had to put a little black shit on everything I put on, you know what I mean? It was either in my shoes, or a little belt, something.”

In the late 1940s, Miles’s career was moving at breakneck speed and he was happy at home with his family. He had married his high school sweetheart, Irene, in 1943, and they had two children—Cheryl Anne, born in 1943, and Gregory, born a year later.

(They would have a third child, Miles, Jr., in 1950, and Miles has another son, Jean-Pierre, from his second marriage, to Frances Davis.)

Miles was playing with the most acclaimed jazz musicians of the time. he finished third in the Metronome jazz poll in the trumpet category, behind Dizzy Gillespie and Howard McGee. His landmark recording, Birth of the Cool, was right around the corner.

But there were dark clouds gather ahead: heroin.

Heroin, for many musicians, was the drug of the day. Fats Navarro, Charlie Parker, Tadd Dameron, Gene Ammons, and Bud Powell were among the many well-known jazz musicians who had severe heroin problems. It would lead to the death of all of them.

But Miles’s addiction caught everybody by surprise. He was thought to be so clean, so disciplined, so middle class that many felt he could never fall victim to heroin. But there he was, up on the bandstand or sitting at the bar during a break, a cigarette with a long burning ash in one hand, a drink on the bar, nodding off and scratching, his eyelids drooping low as his elbows. Miles told Nat Hentoff that he got strung out on “smack” because “I got bored and was around cats that were hung. So I would up with a habit.”

Miles fell so low that he would do anything to get money to feed his habit. His father sent money to try to help him, but he spent most of it on drugs. His public playing became sporadic because of his increasing drug use and club owners’ reluctance to employ him.

He turned to pimping to feed his drug habit.

“I was a pimp,” Miles says. “I had a lot of girls. They didn’t give all their money to me; they just said, ‘Miles, take me out. I don’t like people I don’t like. I like you, take me out.'”

On one occasion, Clark Terry came across Miles on the street, looking down and out. “He was wasted,” Terry said, “actually sitting in the gutter. I asked him what was wrong and he said, ‘I don’t feel well.'” So Terry bought him some food and took him to his hotel room around the corner. “You just stay here,” Terry told him, “get some rest, and when you leave, just close the door.”

Terry, who was playing with Count Basie’s band at the time, was just about to board the band’s bus to go on the road. “But,” he says, “the bus was delayed longer than I’d expected, so I went back to the room. Miles had disappeared, the door was open, and all my things were missing. I called home, St. Louis, and told my wife to call Doc Davis to get Miles, because he was in bad shape and had become the victim of those cats who were twisting him the wrong way.

But Doc Davis was very indignant. He told her, ‘The only thing wrong with Miles now is those damn musicians like your husband who he’s hanging around with.’ He was the type of guy who believed his son could do no wrong. So he didn’t come get him.”

Miles meandered all over the country causing bad scenes. He moved in with Max Roach in Hermosa Beach, California. After a few weeks, he had run up bar tabs at a club called the Lighthouse that he couldn’t, or wouldn’t, pay. After several arguments with the bartender one night, he started getting on Roach.

“But after the argument,” says Miles, “Max gave me $200, put it in my pocket, and said I looked good. It drug me so much. I said, ‘That motherfucker gave me $200, told me I looked good, and I’m fucked up and he knows it.’ And he’s my best friend, right? It just embarrassed me to death. I looked in the mirror and said, ‘Goddamn it, Miles, come on.’ So I called my father and he sent me a ticket back to East St. Louis.”

He left immediately and found his father waiting for him. he told Miles, “You have to do this by yourself, you know that, ’cause you have been around drugs all your life. You know what you have to do.” Miles immediately went and locked himself in his bedroom, stared at the ceiling, and cursed for 12 days.

“Sugar Ray Robinson, the boxing champion, inspired me to kick my habit,” Miles says. “I said, ‘if that mother can win all those fights, I can break this motherfuckin’ habit.’ I went home, man, and sat up for two weeks and sweated it out. I laid down and stared at the ceiling for 12 days and cursed everybody I didn’t like. I was kicking it the hard way. I lay in a cold sweat. My nose and eyes ran. I threw up everything I tried to eat. My pores opened up. Then it was over.”

After a period of recuperation, Miles went to live in Detroit because the city had an impressive array of local jazz talent for him to play with and hard drugs were not as prevalent there as they were in New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. When Miles finally went back to New York in the spring of 1954, many found him changed. Babe Gonzales, the famous jazz singer, said, “When he was strung out on heroin—and he’s one of the very few who broke the habit all by himself, completely, without treatment—Miles was desperate enough to fall in with some pitiless people. Some of them exploited him musically, made him play for very little bread, but he needed that little bread.”

“Also, the hoods who ran the jazz clubs in New York used to beat up on Miles and Bud Powell and other musicians who were strung out and in hock to them. Miles has always been a proud man, and while they didn’t break him, they hurt him for a long time. Ever since then he’s been leery about everybody. With exceptions—and they never know who they’ll be.”

“He thinks that most people are full of shit,” says Tony Barboza. “But if he likes you he treats you like a brother, a friend. With most people he’s very arrogant and tough. He protects himself with his arrogance. He intimidates people, and people don’t fuck with him if they don’t know what they’re talking about. Here’s a man who has lived his life and is a genius. But he’s still a brother off the block. He can be angry with you one minute and back to laughing with you the next. And he’s playful, too. But he needs one-on-one strength. That’s why he fucks with people. It’s like revitalization for him.”

* * *

Miles’s landmark Birth of the Cool (recorded during three sessions, two in 1949 and one in early 1950) marked him as a leader of a new generation of jazz musicians. Remarkably, despite his drug addiction, Miles had produced a number of great small combo albums, including Blue Haze, Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants, Bags Groove, Walkin’, Miles Davis Volumes 1 and 2, Relaxin, Workin’, Steamin’, and Collectors Items. He worked with the creme de la creme of jazz, and in all but a few instances, he was the leader.

In 1955, Charlie Parker died at the age of 34, succumbing to years of abusing his body with alcohol and drugs. Miles had kicked his habit and was back in the recording studio with a vengeance.

It was 1955, and Miles was on the phone, trying to find Sonny Rollins to be a part of his new band. The problem was that Rollins had become a desperate drug addict and had disappeared somewhere into the maze of Chicago’s black South Side. When Miles finally caught up with him, Sonny declined his offer.

That left Miles in a bind for a tenor saxophone player. He settled on a young saxophonist out of Philly named John Coltrane, an unknown and raw player who was the same age as Miles. Coltrane would become the most influential tenor saxophonist of his time. With Coltrane, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, “Philly” Joe Jones on drums, and Miles on trumpet, this group became the most important jazz quintet of its time.

Hamiet Bluiett, the renowned baritone saxophone player, recalls that Miles’s music during that period was such an influence on him, he had to force himself to stop listening to Miles fora while so he could concentrate on his own music. “I worshipped every record Miles made. I couldn’t wait to see what his new direction would be. Back then, jazz was on the jukeboxes, and if you were hip, slick, and advanced, you listened to jazz instead of rhythm ‘n’ blues. And you aspired to be like Miles.”

Miles became a pacesetter in music, style, fashion, and attitude, the leader of a new generation of American artists that included Marlon Brando, Norman Mailer, James Baldwin, Jackson Pollock, Elizabeth Taylor, Harry Belafonte, and Sidney Poitier, among others.

“What Miles did for me and others back in the late 1950s and early 1960s,” say Ron Milner, the highly respected playwright from Detroit, “was give us this cool arrogance. His attitude said that you could stand your own ground, do it your own way, that you had—if you looked for it—a singular, isolated self and that you could stand on it if you could pay for it. It was inspiring.”

Miles Davis reigned as king of all jazz. His recordings on Columbia (he had switched from Prestige) were superlative, including Milestones, Kind of Blue, ‘Round About Midnight, Jazz Tracks, Porgy and Bess, and Sketches of Spain, which were notable for the brilliance of Miles’s playing and composition. These recordings were the seeds of the fusion and avant-garde movements.

Although Miles was at the pinnacle of his success and popularity, he was beginning to get restless about the music he was composing, his own playing, and the makeup of his bands.

“The way I was playin’ was kinda gettin’ on my nerves,” Miles says, pulling at the frazzled ends of his hair. These days he’s wearing his hair straightened. It has grown thin on the top, and the way he wears it pulled back, showing off his high forehead and large, expressive eyes, can give him a severe look that hides his playfulness.

“You know,” he continues, scratching his chin, “it’s like a favorite pair of shoes that you wear all the time. you got to change them. I had to change my music, my approach to it, you know what I mean? The way I played, what I played.”

When Tony Williams, Herbie Hancock, and Wayne Shorter joined Miles and Ron Carter in the band in 1964, the change had a profound effect on American music.

“If we played a song for a whole year and you heard it at the beginning of the year, you wouldn’t recognize it at the end of the year,” says Miles. “Because the way the music was played had changed so much. Tony is a little genius. I had to react in my playing to what he was playing. And this goes for the whole band. The way we all played together changed what we were playing each and every night. And, man, it was great.”

“I liked Miles’s concept, especially with Tony Williams,” says Olu Dara, the exciting cornet player, “because the trumpet and drums are like a family. A great trumpet player can make a drummer great by giving him space to play. Miles, because of his use of that space, created a conversation with Tony. Call and response, an African thing. That was the greatest thing I had ever heard, those musical conversations between Tony Williams and Miles Davis.”

It was so because of the playing and musical theories of one of the most misunderstood and maligned musicians of his time, Ornette Coleman, the alto saxophonist from Fort Worth, Texas, who had been laughed off many bandstands in the ’50s and ’60s by jazz luminaries, including Miles himself. But in the middle to late ’60s, Miles began paying attention to what Coleman was composing and playing.

“The one thing Miles has always had is an almost perfect melodic order,” Coleman says. “Melodic order is what I call the internal unison that everyone is looking for that makes them play their own voice. Miles discovered that he was playing four notes on his trumpet when he played one. That’s my theory of harmonics. He discovered that Don Cherry was playing transposed saxophone solos on trumpet. This is what he discovered in music that made Bitches Brew so successful. Miles added rhythm to the concept, and rhythm is what makes western music popular. He put the backbeat in and put the drums out front and not top, like in African music.”

By 1969, Miles had had his first hip operation, divorced his second wife, Frances, married a young black singer and songwriter, Betty Mabry, and watched his popularity and record sales slowly decline. That year Betty gave a party at their Manhattan townhouse and invited all of her girl friends and Jimi Hendrix.

Betty Mabry Davis’s scene was the rock crowd, whose music was now the thing in America and the world. Coltrane had died in 1967. So the party at his home was geared to put Miles in touch with Hendrix, the uncrowned king of this new music.

There was talk of a musical collaboration between them. But because of a prior engagement Miles could not attend the party. However, he left some music for Hendrix to read. When Miles called to discuss the music, he discovered that Hendrix couldn’t read music. Though the collaboration never came off, Hendrix, a master user of electronics, had a profound effect on Miles.

“Jimi and I got to be friends. He used to come by the house,” Miles says. “He wasn’t a schooled musician, but he could play. I used to show him stuff. I like the way he played. He played natural. Like Sly Stone. They was both bad motherfuckers.”

Both Sly and Hendrix, along with Coleman and the then emerging rock music, had an impact on Miles; he began to use electrical instrumentation extensively.

New musicians were showing up on his albums: paints Chick Corea and bassist Dave Holland on Files de Kilimanjaro, Joe (then Josef) Zawinul on electric piano and organ, and John McLaughlin on guitar on In a Silent Way.

The band underwent an entire metamorphosis, with Lenny White, Jack DeJohnette, and Charles Alias all playing drums, Jim Riley on percussion, Harvey Brooks on Fender bass, Bennie Maupin on bass clarinet, and Larry Young on electric piano. These musicians joined with Dave Holland, John McLaughlin, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, and Joe Zawinul on Bitches Brew.

Bitches Brew was more than a forward-looking album; it was an event. “Miles wasn’t prepared to be a memory—somebody to go and see because you used to dig him,” says Dave Holland, then Miles’s bassist. “He wanted to be somebody who appealed to the generation that’s happening now. And he’s always done this. He always makes music that goes right to the next generation.”

“Bitches Brew devastated a lot of people,” says George Butler, “because suddenly, here was Miles using electrical instruments, synthesizers, and R&B rhythms and incorporating all of that with jazz stylings. Many people were content just listening to Sketches of Spain, Kind of Blue, Filles de Kilimanjaro. Suddenly, Miles makes this drastic and dramatic musical change, and it was just really distressing to a lot of people.”

Bitches Brew was released in 1970. By this time Miles was already experimenting in live performances with an electric piano, electric guitar, and electric bass.

But if Bitches Brew was a critical and commercial success, it was the beginning of a schism in the Miles’s audience that still exists. Many of his most loyal admirers turned off and tuned out of his new music.

The albums that followed—with few exceptions—caused many critics to howl in protest. But Miles was reaching out to both a younger black audience and a young white rock audience.

To keep up with the changes in his music, Miles’s fashions also underwent a remarkable transformation. Miles, who had popularized the “cool” look with his Italian and British suits, was now wearing mod threads, flowing African robes and shirts with fringes, knee-high leather and cloth boots, scarves, and tight-fitting leather jackets. It was still hip and ahead of its time, but it had been definitely influenced by the rockers.

He also took issue with the term jazz. “The more they use the word jazz,” he says, continuing his feverish drawing, “the more people didn’t want to hear that kind of music anymore. It’s diminishing, because it don’t mean anything. It don’t do nothin’. I don’t know what it should be called. Maybe it should be called social music.”

Miles was now playing large stadiums and rock clubs. he was opening for Lauro Nyro and the Band, among others. The younger audience was groping with his new, free-form music. They were unfamiliar with the African rhythms he was playing. They were accustomed instead to rock’s insistent drum backbeat and a rock-steady bass line (elements Miles would incorporate into his later music). But they hung with each other at the same time that many of the older audience had begun drifting away.

* * *

During the early morning hours of October 9, 1972, Miles, out for a spin in his gray Lamborghini sports car, crashed into a traffic island near 125th Street on New York City’s West Side Highway, totaling the car and breaking both legs. On crutches, he began playing again in 1973 with a new band.

The music he was now playing had moved away from individual soloists and into a collective musical sound with multiple rhythms and textures. It was almost beyond western notated musical concepts, beyond transcription.

In 1975 he was rushed to a hospital suffering from pneumonia. later that year he had a hip operation and received an implant. Cannonball Adderley, his old friend, died that year. And that year, Miles disappeared from the music scene.

“Miles left because of a combination of things,” says Max Roach. “When you’re black and well known and you’re in this business, you’re never really compensated for what you have contributed to the industry. So during the course of your climb to fame and notoriety it can sometimes make you bitter, and you might get sick psychologically.”

“I don’t think Miles was so sick physically—though he was that too—as much as he was sick of the music business. Because if you’re very sensitive and tough at the same time, like Miles is, and if you don’t have to take shit economically—and Miles didn’t—then you just forget it, like Miles did, for a whole. But he was being monitored by Dizzy, myself, and others the whole time he was out. We knew what was going on in his life because one of us was always going by to see how he was.”

Miles hardly ventured out of his house. There were persistent rumors that he had a large cocaine habit, that he had cancer, that he was hanging out in the early morning in numerous after-hour clubs. “I once saw him sitting outside his house when I passed by on my way to a photo shooting,” says photographer Tony Barboza, who has been photographing Miles since 1971. “He seemed so sad. Really lost. It seemed like he was lonely, like he didn’t have any close friends. I really felt sorry for him. After I left him, I just went into Riverside Park and cried and cried.”