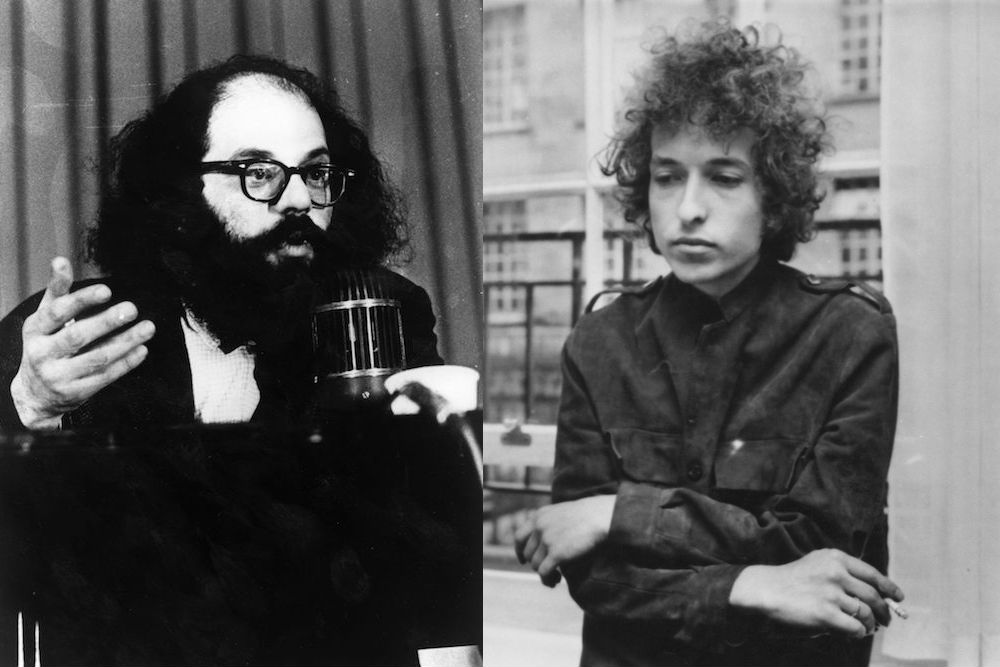

In a career as thoroughly observed, documented, and analyzed as Bob Dylan’s, the emergence of any previously unseen or unheard material is big news. If that material comes from one of Dylan’s prime creative eras–the 1965-66 tour, say, during which the legendary songwriter hired a fire-breathing backing band to help him “go electric” for the first time–the news is even bigger. And if the material happened to be captured by another artist whose legend is on par with Dylan’s–one of the most celebrated American poets of the last century, for instance–you’re looking at a bonafide historical artifact, whose resonance should extend far beyond the cult of fanatics who make up the general audience for Dylan ephemera.

That’s exactly what we got last week, when, with little fanfare, two recordings with nearly identical titles appeared on YouTube. With some interruptions, they document two Dylan shows from 1965, near the beginning of that fateful tour: one in San Francisco on September 11, 1965, and the other in San Jose from the following evening. As you might expect, the performances are enough to knock you out, but the sound quality is up and down. If you’re one of the aforementioned fanatics, you’ll find a lot to love; if your fandom more casual, you’re probably better of listening to one of the much clearer tapes from the same era that have been released commercially.

But anyone with an interest in the American culture of the ’60s will be fascinated with what comes before and after the music. The bootleg taper we have to thank for these recordings is Allen Ginsberg. He and Dylan had been friends for a couple of years already in ’65, and he was testing out a new piece of equipment at the shows, with Dylan’s personal permission. We know the part about Dylan’s permission is true because we can hear the musician giving it, as part of a 20-minute backstage conversation between the two icons that’s preserved at the beginning of the first tape.

The first tape opens with Ginsberg’s bookish Manhattan patter, describing the “absolute, beautiful precision” of his tape recorder, which, he says, he recently purchased for $500. “I don’t know why the fuck I don’t get one of those,” Dylan muses, and then he has an idea: “Hey, why don’t you tape some of the concert?” Dylan says he’s interesting in hearing how the band sounds that night, and Ginsberg offers to give him a copy of the tape when the show is over.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=_sSoVMQhivY

If it weren’t for the fact that their circle of acquaintances included several fellow giants of the era, the ensuing conversation might come off like mundane gossip. Dylan says he recently had a long and pleasant conversation with Marlon Brando, about whom he has apparently mixed feelings. “He thinks about the universe, like you,” he tells Ginsberg, then pivots: “He’s just a very plain, simple, common, ordinary, Nebraska cat. Really that is all he amounts to.” Later, Dylan mentions offhandedly that he talked to Phil Spector about making a record with Ginsberg. The titanic pop producer and the iconoclastic poet would have made exquisitely strange bedfellows. Unfortunately, we’ll never know what the collaboration would have yielded, because it never came to pass.

At the beginning of the second recording, Ginsberg speaks with a fan who apparently recognized him outside of the San Jose show. “Allen Ginsberg…is Joan Baez here tonight?” the young fan asks. (She isn’t.) Between Dylan’s two sets–one acoustic, one electric, as was his standard operating procedure in this era–he and Ginsberg resume the previous night’s conversation. For a moment, they engage in elliptical banter about the crowd at the previous night’s San Fransisco show, sounding a bit like caricatures of their own hipster-mystic public personas. “What you see now is a typical concert. Last night, you saw one that was, y’know, pretty wild. I dug it. San Fransisco. I dug… I sort of felt who they were out there,” Dylan raps as he prepares for the raucous second set, which at times unfolded like trench warfare between the artist and an audience that refused to let go of their earnest folk singer. “Who do you feel they are?” Ginsberg asks. You can hear someone tuning a guitar in the background. “I have no idea, none whatsoever,” Dylan answers.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=77QeVTNvfcI

The Ginsberg tapes evidently came from the Stanford University library’s department of special collections, which administers a large archive of the poet’s papers. The library publicized the existence of the recordings in a blog post in 2015, accurately touting them as documents of “a transformational time in Dylan’s performances.” Though the library has digitized over 2,000 recordings from the Ginsberg papers, the Dylan shows still aren’t officially available online–until last week, you had to physically travel to the library to hear them. The new YouTube videos mark the first time the tapes have become available for the wide listening public.

Keith Gubitz, the California-based Dylan collector who uploaded the videos, says that he’s seen his hero play live about “a few hundred times” since first hearing “Blowin’ in the Wind” as an eight-year-old in 1962. He told SPIN that word about Ginsberg tapes began circulating online amongst a community of fellow Dylan enthusiasts in July, but he’s not sure exactly how they made it out from Stanford’s listening room.

“In ’89, I met a guy that was following the Bob tour. He basically was a Deadhead, and saw Bob and decided to switch tracks,” he said, describing his own entry into the world of Dylan tapers and traders. “I met him in line when I was trying to buy tickets, and we hooked up and started following Bob together. We would stay in hotels and dub the tapes right after the show.”

Gubitz isn’t a taper anymore, but he maintains a large collection of other people’s Dylan show recordings on YouTube. He says he’s occasionally run into problems with YouTube pulling his videos down, but it doesn’t happen frequently, and he’s not worried about anything happening to the Ginsberg tapes. You might consider listening to them sooner rather than later, however, just in case they disappear.