On July 13, 1977–a sweltering summer night, 40 years ago today–lightning struck a Con Ed cable draped over the Hudson River, about 40 miles north of Manhattan, setting into motion a series of electrical failures that soon left the entire city of New York without power.

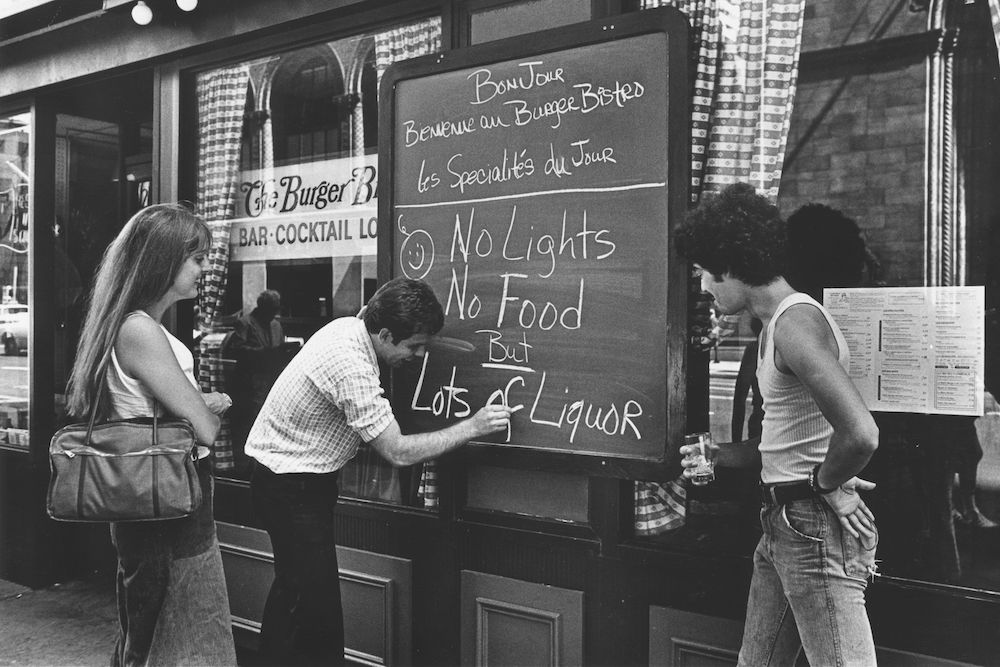

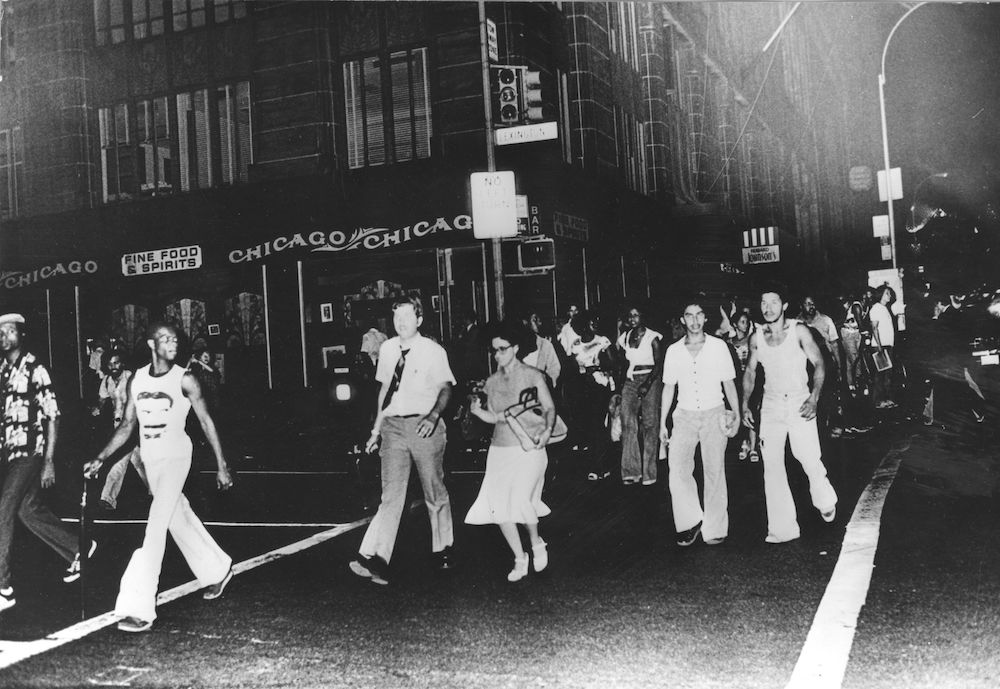

By the time the power came back on Thursday afternoon, entire city blocks were laid to waste. Looters in poor neighborhoods burglarized local stores; petty arsonists and cash-strapped landlords set fire to buildings; according to one account, Brooklyn’s Broadway became a warzone, with cops and looters exchanging open gunfire on the streets and on elevated subway platforms. The ’77 blackout was a defining event of the city’s late-’70s wilderness years. David Berkowitz, the serial killer better known as Son of Sam, had terrorized the five boroughs and lit up the tabloids the previous summer. The year before that, the New York Daily News ran its infamous “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD” coverline, railing against the then-president’s refusal to extend a financial lifeline to a town that was teetering on the edge of collapse and bankruptcy.

But 1977 wasn’t all bad. At the time, New York City was undergoing one of the greatest musical renaissances in modern history, with Bronx teenagers birthing hip-hop at all-night parties in city parks, downtown punks ripping rock’n’roll apart from the inside at CBGB’s, instrumentalists exploring the outer fringes of jazz in SoHo lofts, and renegade composers altering the trajectory of classical music history with a new sound called minimalism.

Former SPIN writer and current Rolling Stone, New York Times, and NPR contributor Will Hermes chronicled the tumult and invention of the era obsessively in his 2011 book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever. The book contains one particularly incandescent passage which takes the reader through the blackout, depicting what several icons of music history were doing when the city went dark. The members of the Talking Heads were placidly grilling hot dogs and hamburgers on the roof of Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz’s building in Long Island City; Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band were in the middle of tracking Darkness on the Edge of Town, and were forced to take a night off.

To mark the blackout’s 40th anniversary, we talked to Hermes about writing the book, and his own memories of that fateful night as a 16-year-old growing up in Queens. After the interview, read an excerpt from Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, in which the pioneering DJ and rapper Grandmaster Caz–then known as Casanova Fly–loses power during a performance.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In the book you have all these great stories of musicians during the blackout: Meredith Monk in a movie theater watching Annie Hall, the Talking Heads barbecuing. How did you go about researching or reporting those anecdotes out?

Anybody who’s a New Yorker, you have your stories about that date, if you were in the city—in the same way that anyone that was there during 9/11 has their stories. They become part of your personal mythology of the city, your battle tales. When I did my research for the book, through books and magazine articles, I was able to find a bunch of stuff. But every interview I did, I asked people what they were doing. Part of the fun of writing that section was wanting to jump-cut between as many disparate scenes as possible, whether it was the cast of [Broadway musical] Beatlemania singing Beatles songs acoustic on a candlelit stage because they couldn’t continue the production on Broadway, or Annie Sprinkle in the middle of giving some guy a blow job on a sex work job she had, or Bruce Springsteen having to bail in the middle of a historic recording.

When people are talking for a magazine feature certainly, but especially for a book, when they’re really laying information down that’s going to become part of the official record, they’re a little circumspect, and maybe a little apprehensive about how you’re going to put things. But ask anyone who was around during the blackout that night, and all of a sudden all guard is dropped. It was the great equalizer. Bruce Springsteen might have been the greatest rock’n’roll star in America, arguably, but he didn’t have any fuckin’ electricity. And neither did I!

Do you remember what you were doing when it happened?

I was out on Cunningham Park, which is in eastern Queens, toward the Long Island border. We were hanging out in the park, probably smoking pot, chilling and talking. The perimeter of this huge field was surrounded by streetlights. And I remember the streetlights going out, not all at the same time, but one after the other, almost like an amusement part or an arcade. I was expecting them to flick back on, and they didn’t.

The people I was with wandered down Union Turnpike, and realized the power was out. We were out there for maybe an hour or two, and it clearly wasn’t going back on. We found people with transistor radios, and they were able to find out bits of information—that the blackout was citywide. Some of the bars were giving out drinks. I remember seeing a bunch of police officers hanging out near this bar on the block. The neighborhood, being what it is—a middle to upper-middle class white neighborhood, with a police presence—there was no crime. There was nobody breaking in stores. It certainly crossed our minds to do so, but we didn’t take any action.

Of course, other things were going on in other parts of the city that were struggling. It was another one of those incidents where the gross income disparities are highlighted, between neighborhoods that are actually really close to each other in New York City.

The next morning, I heard radio reports, and then eventually when the power went on, we saw these incredible televised images of this wild wholesale looting going on. Being foolhardy teenagers, we were like, “Oh damn, we should have gone and gotten stuff somewhere. Music Box Records has a whole lot of stuff I could have cherry-picked!”

What music were you into at the time? If you had gone and cherry-picked a few records from Music Box, what would you have taken?

I was probably right at my tipping point between classic rock, Grateful Dead, Hot Tuna, Jam Band stuff, latter-day Led Zeppelin and British prog rock stuff, and what was beginning to blow up in New York. You have to remember that a bunch of the great New York bands did not record until 1977. The first Television record—I don’t remember whether that had come out yet. Patti Smith’s record was out, and I had it. I had the first couple of Ramones records. I probably would have went out digging for the new punk and new wave records that I hadn’t heard yet. If I’m not mistaken, the Richard Hell and the Voidoids record came out that year. There were a bunch of others. We had a good used record store in town, so I probably would have gone for new stuff and old stuff. The old stuff was cheap, and the new stuff was more expensive. Oh my gosh, records were probably $4.99!

The following is an excerpt from Love Goes to Buildings on Fire

Casanova Fly and Disco Wiz had set up their sound system earlier in the evening at 183rd Street Park. They were prepared for a battle, and if they were outgunned, they wouldn’t be outsmarted. The Master Plan Crew—basically one kid, DJ Eddie, with no skills and a bunch of weak-ass disco records—had challenged them many times, and they’d finally agreed. Eddie had big Cerwin-Vega speakers and a serious amp. But he didn’t know the science of funk.

Caz and Wiz let him go first while they fiddled with their own gear — essentially Caz’s home stereo system — on the opposite side of the park, hooking it up to an extension cord they’d wired into the lamppost. As night fell, it was still near 90 degrees and sticky. Wiz was worried about their amp blowing in the heat. The crowd was getting thicker. People brought coolers with forty-ounce bottles of malt liquor; you could smell the acrid scent of dust being smoked.

When it was Caz’s turn, he slapped the Incredible Bongo Band’s “Apache” on the turntable and let it rip. The conga beats richocheted around the park, everybody in the park shouted their approval, and Caz knew that Eddie was finished. He cued up his second record for the one-two punch: Pleasure’s “Let’s Dance.” “Let’s make it fuh-fuh-fuh-fuh-fuh-fuh-fuh-FUNKY!!” the singer chanted over a churning wah-wah riff. Then the drums crashed in, and the horns, and the kids who came with Caz and Wiz were going bananas.

And then the beats started slooooooooooooooowing down, until they stopped dead.

Time stretched out. The streetlight they were plugged into went dark; then the other working streetlights around the park perimeter cut out, one by one.

“What the fuck did we just do?!,” Wiz yelled. You could barely see your hand; there was no moon.

The crowd in the park muttered and laughed, shouted, looked around. There were no lights in any of the apartment buildings.

Some asked the time; a guy with a glow-in-the-dark watch said it was 9:40. Then someone else yelled: “Hit the stores!”

Others repeated the cry.

People started running towards the shopping strips on Jerome Avenue, West Tremont Avenue, Grand Concourse. One group decided to start the looting with Caz’s soundsystem. Caz and Wiz both pointed handguns at the people they had just been playing records for.

“Go THAT way, motherfuckers!!” instructed Caz, pointing out of the park.

Caz asked Wiz to get some friends to pack up their gear, then dashed off, saying there was something he had to get. As Wiz tells it in his book It’s Just Begun, Caz was back 15 minutes later with a single item: A Clubman Two mixer that he’d been eying at a nearby shop for quite a while