This article originally appeared in the April 1994 issue of Spin.

Coogee Beach, Australia, is what you get when you give English refugees exercise and sunshine and proper dental work. A triple-wholesome suburb set on a sandy cove just east of Sydney–sort of a Gidgetville of juice bars, curry stands, family hotels, seaside flats, and beer gardens–you see more California-style, drop-dead blonds per square foot here than you ever could in Malibu.

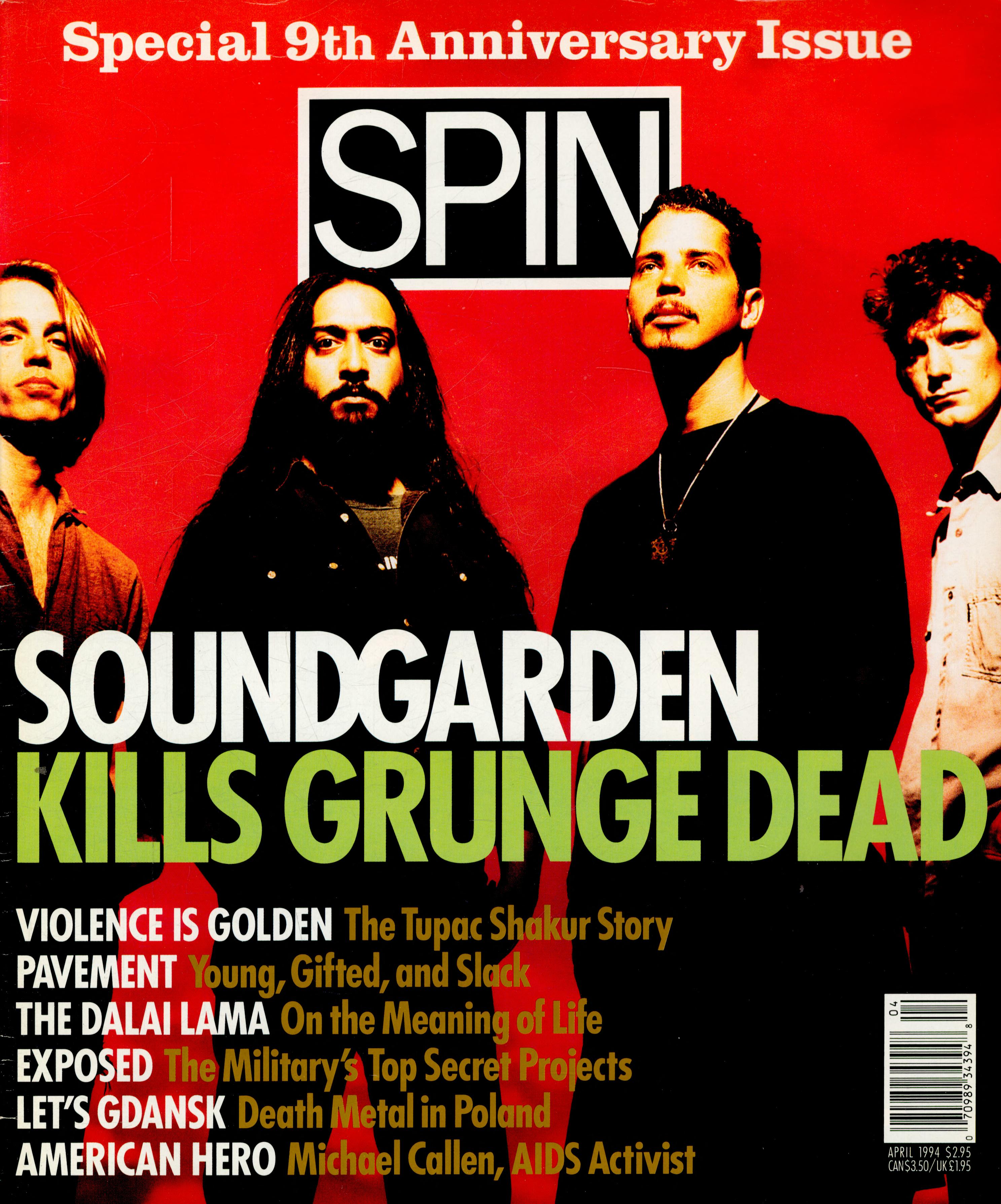

Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil, king of all rock riffs, stands on a beach promenade, gazing sadly into the waves toward Seattle, though on second thought he may be scoping out the topless women sunning themselves on the white sand. Drummer Matt Cameron is checking out wombats at the Sydney Zoo; bassist Ben Shepherd is inside recovering from jet lag; singer Chris Cornell is out on the beach roasting to the raspberry-sherbet rue he will wear for the next week. Tomorrow night, approaching the club where Soundgarden will play, there will be Ministry T-shirts and long hair and Psychic TV tattoos, flannel shirts at the height of the Australian summer, bad skin and Winona-bes, Alice in Chains tapes blasting from cars, and all the goatees and skinny guys with cigarettes that make up the alternative nations of the world. But that’s tomorrow.

“This is paradise,” Thayil says.

The first time I ran into Thayil was at a club called the Off Ramp in Seattle a couple of years ago, just after L7 played a set that had grunge kids hailing off the stage like little Superballs. Thayil, if I remember correctly, was cradling about three Budweisers just in case the bar decided to close before he had slaked his thirst. He decided I looked like a person who needed a drink, and he handed me a long-neck.

“So have you heard the advance tape of Badmotorfinger?” he asked.

I had.

“Sounds too much like Rush,” he said gloomily.

Thayil raised a bottle and clicked it to mine. “Here’s to Geddy Lee,” he said.

Soundgarden’s first EP, Screaming Life, may have seemed like just another obscure indie record when it came out in ’87, but in retrospect the first bow-shot of the modern rock era was fired on the first ten seconds of that limited-edition, blue-vinyl Sub Pop masterpiece (in the opening measures of the song “Hunted Down”). Thayil’s riff consisted of bottom-string guitar notes that didn’t bend, exactly, as much as they refused to commit to a single pitch; Matt Cameron’s drumming was spare and sort of thuddy, but also laid-back in a style common to metal drummers of the time but not to underground art bands. The bass lurked subliminally deep, and most of the space above was occupied by the powerful, piercing cry of singer Chris Cornell, who sounded like a goddamn trumpet. It was a record capable of making you forget everything but the overwhelming need to shake your long hair in front of your eyes.

“Songwriting for me is in the proximity of the possibilities,” Cornell says later.

Soundgarden made music that was simultaneously hard rock and an ironic commentary on hard rock–meta-rock, as it were–but unlike the standard ironic rock take of the third-generation of post-new wave America (the Mojo Nixons and Dead Milkmen and numberless art-school pop bands that sang gentle songs about their toaster ovens) Soundgarden (1) played it dead-on straight; and (2) actually rocked. Soundgardenian meta-rock became the lingua franca of the so-called Seattle sound and its impetus became the reason it is often difficult in 1994 to tell the difference between the alternative-rock station and the heavy-metal station of a big-city radio dial. Man, even their hair rocked.

Back above the Australian beach, outside the hotel where Soundgarden is staying while it rehearses for its first tour since completing its fourth and best album, Superunknown, Thayil gesticulates to make a point, and his half-finished cigarette flies out of his hand and skitters across the sandy pavement.

“My mom’s been going around saying how proud she is of me,” Thayil says, “but she also talks about the good genes she supposes I hate and what my excellent musical upbringing did for me. Sorry, Mom. I know you studies to be a concert pianist at the Royal Academy of Music, I know you were a music teacher for 20 years, but I got my musical education from locking myself in my room as a teenager and listening to Kiss.”

“I listened to all that rock crap in high school,” he says, fishing a cigarette butt (not his) from the ground and looking for a place to throw it away, “but I always hated Led Zeppelin–too pretentious–and Black Sabbath had really cool riffs, but they stretched them out in really stupid ways. we were way more into stuff like Scratch Acid at the time. At first I think we wanted to do, like, Black Sabbath songs without the parts that suck.”

It feels peculiar reporting an entire story on Soundgarden from Australia without even a nod to Seattle–the land of baggies and flannels and Kmart-brand grunge boots, of constant drizzle and excellent coffee. I think about flying up to visit Susan Silver, who manages Soundgarden and is married to Chris Cornell, and asking her to show me around.

“This is the record store where Kim might be hanging out if he weren’t in Sydney,” she might say. “This is the house where Chris and Kim and original bassist Hiro lived when they decided to start the band. Here’s the Soundgarden sculpture the band named itself after. Here’s where they rehearse. Here’s where they played their first show.”

Instead I decide to call Sub Pop prexy Jonathan Poneman, for the quote that is all but obligatory in Soundgarden profiles.

“There’s a perspective, a natural integration of ideas in Superunknown that I don’t think the band has really captured since Screaming Life,” Poneman says. “For some reason, Soundgarden has always been seen as the Seattle also-ran, though they are in many ways the defining band of the regional sound. I have been listening to this record with an intensity bordering on obsession; it redefines an entire genre of rock for the better.”

Huh?

“If anybody is going around saying that Soundgarden is any less important than any other band in this town, tell him that Jonathan Poneman is going to kick his ass.”

Sure thing, dude.

***

Everybody pretty much knows the basic history of Soundgarden by now, that Thayil went to high school outside Chicago with Sub Pop founder Bruce Pavitt and original Soundgarden bassist Hiro Yamamoto; that Pavitt and Yamamato drifted to the groovadelic Washington alternative college Evergreen State, and that Thayil, finding no jobs in Olympia, drifted north to the University of Washington; that Thayil and Yamamoto and Chris Cornell formed Soundgarden as a power trio with Cornell both drumming and singing; that Matt Cameron came aboard as a drummer in ’86, and Ben Shepherd took over from Yamamoto and temp-guy Jason Everman as bassist near the beginning of ’90. “I had been a Soundgarden fan for so long,” Shepherd says, “that when I was asked to join the band, I felt like Charlie Bucket getting the golden ticket to go to the chocolate factory.”

For a while, the band had rotten luck with labels. They left Sub Pop and recorded Ultramega OK for SST just as Sub Pop started getting hot, and they recorded Louder Than Love, an extremely metallic sort of, um, grunge album for A&M, a year before the “alternative” market existed–Soundgarden was sold as a mainstream metal band at a time when gutty, Soundgarden-inspired indie units were knocking off metal bands left and right. While Soundgarden’s Seattle contemporaries in Nirvana and Pearl Jam were busy cultivating the neuroses that would later make them household names, Soundgarden was touring with Skid Row, Danzig, and Guns N’ Roses. Badmotorfinger, Soundgarden’s last record, eked its way to platinum.

Superunknown seems poised to sell far more.

Once the epitome of the long-haired, finely muscled rock god, the newly shorn Cornell sort of resembles Captain Morgan on the spiced rum bottle. Cornell has strong features: a chiseled chin, full lips, a nose that is small but strongly set, searching eyes, and a very expressive face. More important, Cornell may have the only voice in rock that bears relation to the great operatic divas. On a song like “Behind the Wheel” from Ultramega OK, which showcases the power and range of Cornell’s voice the way some Rossini aria might the voice of Metropolitan Opera soprano Dawn Upshaw (who was Thayil’s fourth grade girlfriend), you wait for the high C, you want it, you need the high note as badly as you need more oxygen in a crowded mosh pit.

“We were sometimes perceived,” Cornell says, “as this band who was sort of copying the Sub Pop trend, even thought we had the second release on the label. And I noticed when people wrote articles about Sub Pop we were mentioned, but when the backlash happened we managed to escape it. That always seemed pretty good.”

The other thing you should know about Soundgarden is that, despite their manly demeanor, they’re about the farthest thing from a party band you’ll find, though they do like to eat. The tour manager wants to take them out to dinner at an Italian café in neighboring Bondi Beach, but Matt Cameron spotted a place earlier that serves blue-eyed cod and kangaroo filet. The band troops up to Cameron’s restaurant for some real Australian food, and plenty of Australian beer. “The chef prefers to serve the kangaroo rare,” the waiter says.

“Rare!” Thayil exclaims. “Is it possible to get some medium ‘roo?”

“I’m not sure,” says the waiter, looking doubtful, “but I’ll check for you.”

“Man,” Cornell says, “if people find out we’re eating kangaroo, some of them are going to be really bummed. I think I’ll stick to the lamb.”

Cameron orders ‘roo for the table, cooked medium, with fried eggplany and a roasted red pepper sauce. The ‘roo is quite good.

“We were up in Vancouver playing a show with the Melvins,” says Cornell, poking at his lamb chops, “and when we finished our set, [Skid Row’s] Sebastian Bach was waiting for us in our dressing room all by himself, with his fist wrapped around a bottle of Jack Daniel’s. He looked at us, and he could kind of see that we were putting on our coats or something, and he was laughing hysterically; we couldn’t figure out why. We all filed out. He said mid-laugh, ‘I can’t believe this. You guys are leaving me alone at your own show.’ We all went our separate ways and he was sitting there getting fucked up in our dressing room. A lot of those heavy-metal guys seem to think that it’s part of their job to keep the party going.”

“You know,” Thayil says, “people always think of us as macho pigs. We play masculine music, really powerful rock. We rock without the long, pointless sections that go nowhere, the stupid guitar solos, the lipstick, and the codpieces. We are what we are, and I guess we’re not especially interested in showing a sensitive female side. But I think one of the reasons we’re considered so macho is because we’re unavailable. Chris is especially sexual onstage, but after the show he doesn’t belong to you, and I think people sense that. I think we may scare young women.”

“Last year,” Cameron says, reaching for the place of kangaroo, “Sassy readers voted us the ugliest band in America, which is pretty cool, but sometimes the politics seem a bit heavy-handed. We did a show in Olympia right before Badmotorfinger came out, and people there were starting the riot grrrl Kill Rock Stars label at that point, and there were T-shirts, and they were great. I asked if I could buy one of the T-shirts, and the guy said, ‘No, man, you’re a rock star.’ I thought to myself, ‘What a closed-minded idiot!’ I mean, we struggled a lot. We were poor. For years, we slept on people’s floors right next to the cat box when we went on tour. We don’t have the attitude that people seem to think we have, the sexist posing, the drugs.”

“But Superunknown is a very stoner-friendly record,” says Cornell, “which is funny, because none of us really do drugs. If you listen to it straight, it’s great, but if you get really stoned, it can seem that the whole thing was conceived for that state of mind. I can’t explain why.”

“In the LP version,” Thayil says, “we even have a gatefold, so that the kids in the Midwest can use it to clean their pot.”

A couple of days and a harrowing plane flight later, the band makes it to a resort town called Surfer’s Paradise, which is more or less the Miami Beach of Australia, a skinny coastal town about an hour south of Brisbane, pounded by waves and plagued with jellyfish, crowded with high-rise hotels popular with Japanese honeymooners. Surfer’s Paradise is the jumping-off point for the Big Day Out tour, a sort of Australian Lollapalooza that Soundgarden will headline this year. In the lobby bar of one of the tallest hotels, Cornell and Thayil are settling back with a couple of beers when Billy Corgan from Smashing Pumpkins wanders through, and decides to join them for a strawberry margarita. Corgan chatters about the pain of his life, the supposed incompetence of his band (everybody rolls their eyes), the lifesaving virtues of Jungian therapy, bands that suck. Cornell gets up to leave. Corgan tells Thayil how important Soundgarden used to be to him, and he baits him by saying that the Pumpkins sometimes do a cover of Soundgarden’s “Outshined” that segues into a Depeche Mode song or something.

“I’m think of making my next album really new wave,” Corgan says, “like ’83-’84 new wave, not like Berlin. I spend all my time doing things that may be a bit tangential, but I think I’m going to go back to the core, the heart music. Echo and the Bunnymen.”

This is standard stuff to anybody who has read even a single Billy Corgan profile, the basic curriculum of Pumpkins 101. But Thayil isn’t buying. He’s sore.

“Don’t you see,” Thayil says, “you’re this incredibly talented guy. People like your music. You have a good band. You sell a lot of records. You don’t need all this…stuff.”

“What sign are you?” Corgan asks.

“What do you mean, what sign am I?” Thayil says. “What difference could that possibly make?”

“C’mon,” wheedles Corgan, “when is your birthday?”

“All right, goddamn it: September 4th.”

“Aha!” Corgan says. “A Virgo. You’re argumentative.”

“Damn right, I’m argumentative,” Thayil says, and takes a long, angry pull at his beer, “which you should know because I’ve been arguing with you for half an hour, not because of any sign.”

“I’m a Pisces,” Corgan replies. “We pick up on those things.”

A minute later, Corgan, still probing, finally finds the key to Thayil’s heart: “I hate how in magazine pictures, they always stick me somewhere in the back.”

Thayil explodes: “What do you mean? You write all the songs, and you do all the interviews. You play the instruments on the album. You control the band to the extent that most people think of Smashing Pumpkins as the Billy Corgan Experience, and all you care about is some photography?”

“But I hate it,” Corgan says, “it means they don’t think I’m the cute one.”

“Ooh,” Thayil says a little too loudly as Corgan walks away, “I’ll bet he’s going to call his therapist in Chicago, wake her up at four in the morning, and tell her about that big, mean bear who made fun of him.”

The next day at the Big Day Out festival, Thayil is talking to Kim and Kelley Deal in the Breeders’ dressing room when Corgan walks past wearing a long-sleeved Superman T-shirt like the one your four-year-old nephew probably owns.

“You hurt me deeply,” Corgan says, touching the giant S on his chest and pouting. “You hurt me deeply in my heart.” The Pumpkins go on to play the best set anybody has ever heard them play, their usual passiveness and precision overlaid with an unfamiliar scrim of anger that throws their music into brilliant relief.

Matt Cameron is a little astounded. “Kim should rent himself out as a tour shrink,” he says.

The first date of the Big Day Out tour is held on the periphery of a house track south of Surfer’s Paradise. The concert site absorbed seven inches of rain the day before, and the ground is swampy, cratered with squishy footprints, and ripe with an animal aroma some charitably call “fertilizer.” The mud is further ground into adobe by the force of 26,000 slam-dancing feet, and by the time Soundgarden goes on late that night, it is ankle-deep and black as tar. It’s like the La Brea Tar Pits out there–you keep expecting to see a pogoer swallowed whole by the muck.

Through the rear window’s venetian blinds on the motor home that serves as Soundgarden’s dressing room, you can see into the next trailer. We watch the Ramones begin to rehearse silently. Maky tapping out the rhythms on a drum pad, CJ and Johnny playing the vicious downstroke riffs that are at the core of the music. The Ramones don’t seem to know anybody can see them, but Soundgarden can’t help watching, involuntary voyeurs to the most primal process in rock’n’roll: 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4. Later, everyone troops out to watch the Ramones’ set, which is awesome. Neither Thayil nor Shepherd can resist sagging to the splits and doing a little air guitar during “Teenage Lobotomy,” but somehow what went on before was more private, more powerful; it belongs to them.

Soundgarden’s set that night is an almost surreal, underwater thing, sounding more like Debussy than, say, Mudhoney at a distance of a quarter mile. During “Spoonman,” a 7/4 stomp that is the first single from the new album, one kid toward the back intentionally falls face-first into the much, and then a few more do, and then a quarter of the crowd is covered head-to-foot in stinking black ooze and grinning from the wonder of it all.

After Soundgarden’s set, the guys pile into the van, and a local radio station crackles into life. “Was Chris Cornell’s voice as magnificent as it is on rec-awwd?” asks a DJ to a woman presumably calling from one of the dog track’s pay phones.

“Oh yes,” says the woman. She sighs. “It was increidiboo.”