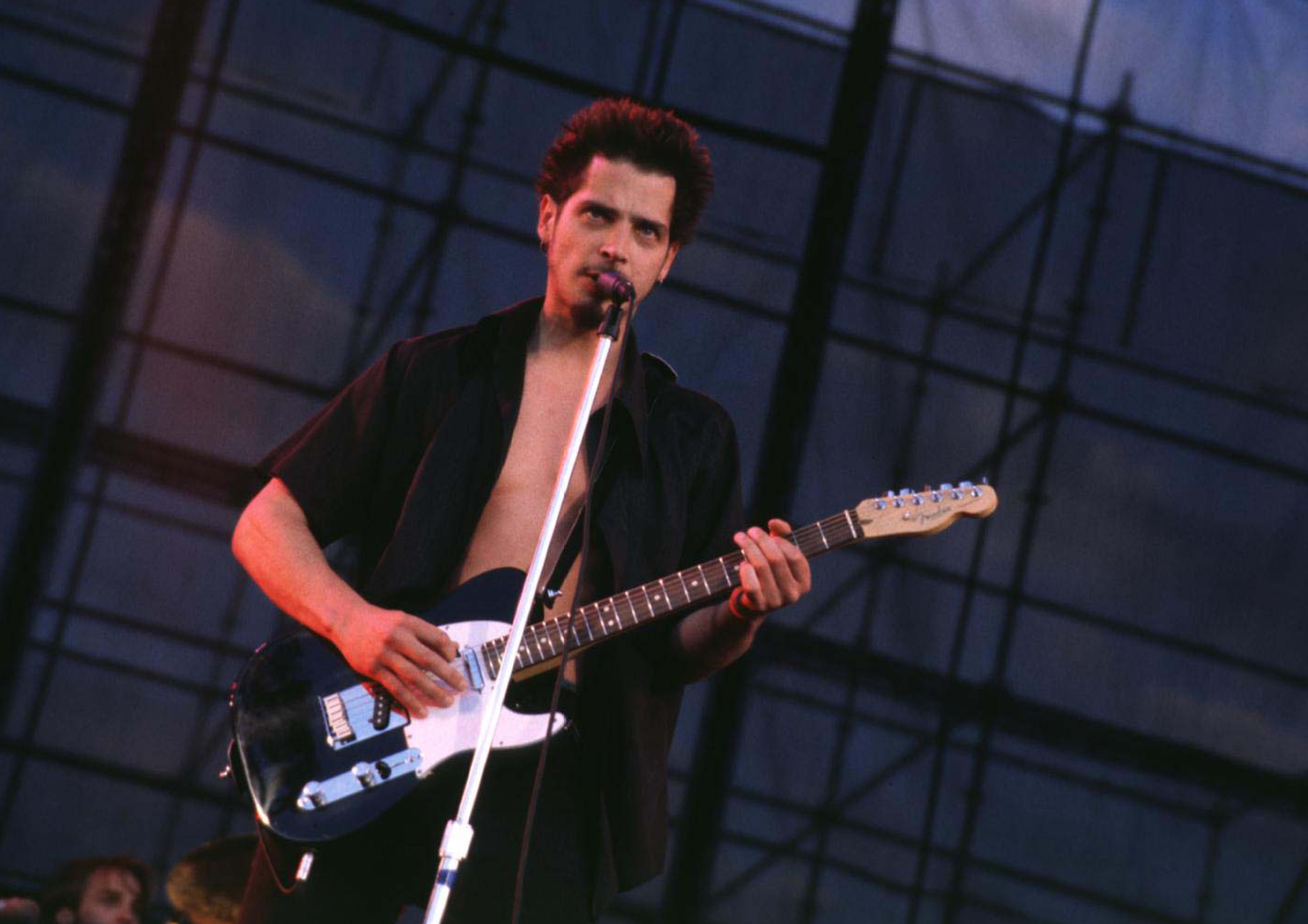

Chris Cornell, former frontman of Soundgarden and Audioslave, passed away May 17, 2017 in Detroit at the age of 52. In light of his passing, we are republishing feature on Soundgarden’s breakup, which originally appeared in the July 1997 issue of Spin.

“Once you sort of define what the band is, then you have to move on from there or you’re finished, you’re done,” Soundgarden frontman Chris Cornell told Spin in the spring of 1996. On April 9, 1997, less than one year later, Soundgarden’s label A&M Records issued a terse press release stating that, after 12 years, the Seattle foursome had “mutually and amicably disbanded to pursue other interests.” Had the pioneering alternative rock act simply run out of ideas, or were there more negative forces at work?

It’s still unclear, as the fiercely private band–Cornell, 32; guitarist Kim Thayil, 36; drummer Matt Cameron, 34; and bassist Ben Shepherd, 28–isn’t talking. “People are digging and there’s nothing to dig up,” says Susan Silver, Cornell’s wife and head of Soundgarden’s management company Silver Management. “They looked honestly at themselves and decided it was time to move on.” A Seattle insider portrays the band as a close-knit family that finally succumbed to a dislike of touring, one that had gradually increased as members moved into their 30s. “This is the most boring breakup in history,” says the source.

Unsurprisingly, however, rumors of internal conflict are flying, the most persistent of which pits Cornell and Cameron against Thayil in a battle over the evolution of the band’s sound during the recording of their fifth and final album, Down on the Upside. A former associate says tensions flared further during Soundgarden’s stint with Lollapalooza last summer. “The band was miserable,” says the source. “They expected it to be like 1992 when they hung out with the other bands. But Metallica [the headliners] kept a very separate camp and there was fighting between managements over billing.”

Also Read

Every Soundgarden Album, Ranked

After Soundgarden toured Europe the following September, morale was so low that Silver hired Offspring manager (and old friend) Jim Guerinot to help make the upcoming U.S. leg tolerable. But by December the band had decided to take the summer off, which would have been their first such vacation since 1988. Soundgarden’s final concert in Honolulu, on February 9, proved disastrous. Before a less-than-capacity crow, Shepherd threw one of his increasingly common tempter tantrums and stormed off stage. Cornell, “anxious to start a solo career,” according to a source at A&M, had had enough.

In one sense, the breakup is a sign of the times. With alternative rock sales stagnant, major record labels have been trimming both their rosters and the staff hired to support the alt-rock boom of the early ’90s. Seattle, grunge’s birthplace, has been hit especially hard: Sub Pop, once the home of Soundgarden and Nirvana, is fending off a rumored shutdown, while both Silver Management and Curtis Management (which handles Pearl Jam) have scaled back. “We went from cover stories and an influx of every A&R person and suburban teenager to clubs closing down and Seattle reverting back into the quiet town it once was,” says Daniel House, president of Seattle’s C/Z Records. “It’s quite sad, but it’s also almost a relief.”

In any case, Soundgarden will be remembered as the reformers that brought the indie-punk aesthetic to hard rock, became the first “Seattle Sound” band to sign with a major, spawned countless imitators, and sold 20 million albums in the process. “Soundgarden paved the way for a lot of bands,” says Jason Finn of Seattle’s Presidents of the United States of America, who collaborated with Thayil on their last album. “Now they’re pulling the plug with dignity. They’re not grasping on to the end of some tired old movement–they’re moving forward.”