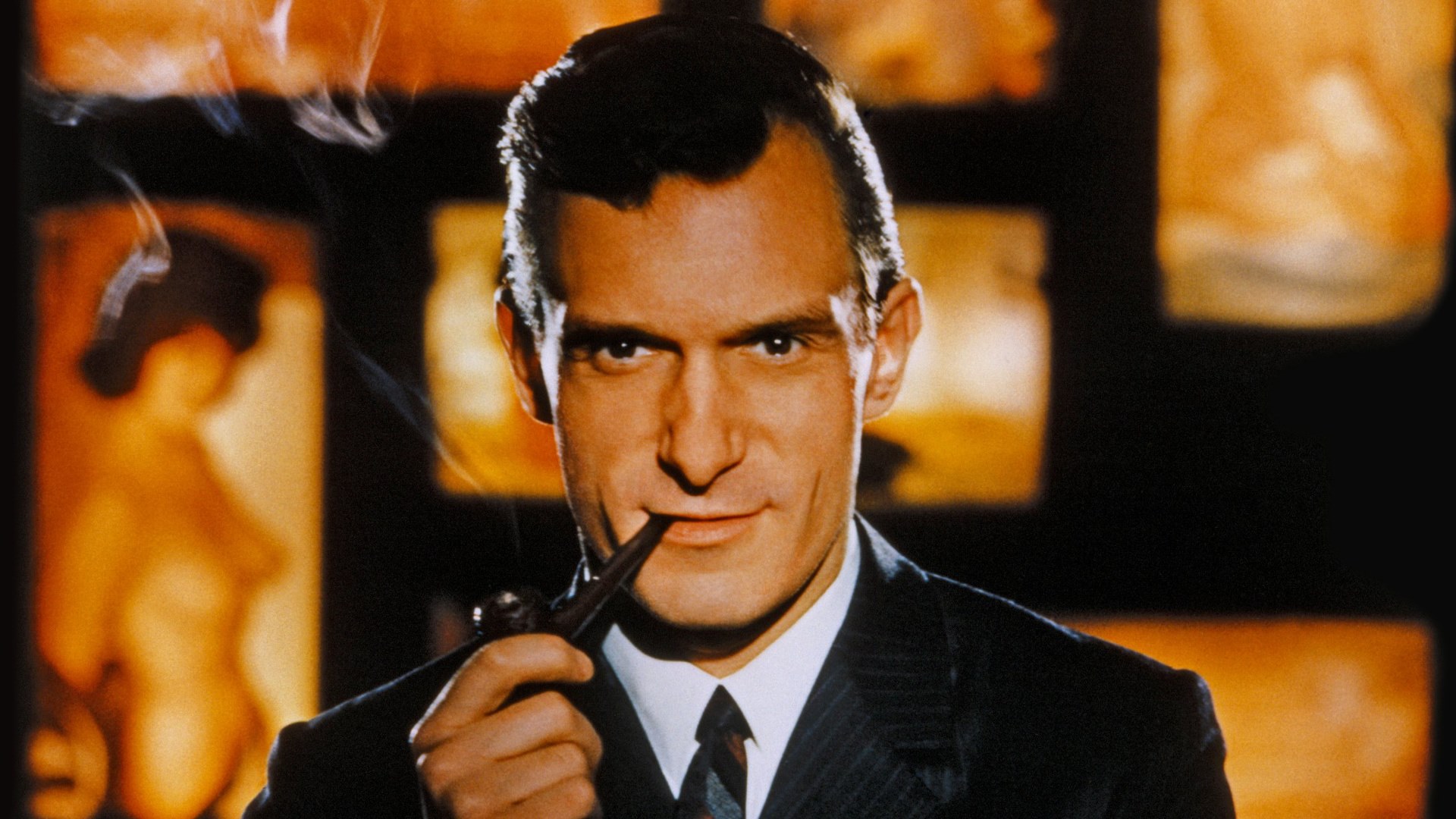

What do we talk about when we talk about Hugh Hefner? If your answer is something like “an eccentric billionaire weirdo” or “a rich, bathrobe-obsessed creep,” then Amazon Video’s new docuseries American Playboy: The Hugh Hefner Story will not be as perverse or condemning as you might hope. The show, which curiously mixes Mad-Men-aspirant reenactments with talking-heads interviews and archival footage, exists more to rehabilitate the image of Hefner and Playboy, reminding contemporary viewers that the men’s magazine was once hip and cutting-edge, at least for roughly the first two decades of its existence. It is, at no point, explicitly damning, or even very critical, of Hefner or his legacy.

Certainly, there is something of the Straight Outta Compton effect here: Like the N.W.A. biopic, the film was produced by Alta Loma Entertainment, which is owned by Playboy Enterprises, who are still in business and have a brand they have a vested interest in protecting. But this doesn’t just pose an issue for those fixated on the documentary’s shirking of any perceived responsibility–perhaps, creating a less aggrandizing portrait of a man who has been accused, in recent years barely covered by the series, of being an accomplice to Bill Cosby and of running his notorious Playboy mansion “like a prison.” It will annoy those seeking an objective, full-bodied, and engaging portrayal of one of America’s most bizarre business mavericks. The series does not revel in Hefner’s quirks, or illuminate his psychology apart from how he makes business decisions. Instead, it works overtime to make him seem like a normal, red-blooded, ambitious, all-American male, albeit one who’d dedicate his life to enabling horniness. Hefner, the show argues, was primarily distinguished merely by the richness of his vision, business smarts, progressive attitudes, and prodigious desire to stay sexually active and independent.

This element of the show points to the biggest obstacle for entry in American Playboy. Even in its first four episodes, which detail the creation of the key building blocks of the Playboy empire—the magazine, the Playboy’s Penthouse TV series, and the franchise of exclusive Playboy clubs—the show feels unnecessarily protracted. At the center of the drama are Hef’s “Eureka!” moments and business breakthroughs—initially, buying nudes of Marilyn Monroe for a mere $500 for Playboy’s first issue. The soundtrack stops dramatically as we watch the series’ Hefner surrogate (played by Matt Whelan) invent the centerfold by folding a piece of paper, and put the finishing touches on the prototype of the bunny costume, which the documentary treats as an iconic symbol of American culture on the level of Washington crossing the Delaware. There is high drama when obstacles for the business are overcome, even down the level of banality of getting Diner’s Club as an advertising client.

American Playboy is a product of the age of drawn-out, narrative podcasts and in-depth, serial documentaries like O.J.: Made in America. Like the Academy-Award-winning Simpson film, Amazon’s show not only aims to examine the particulars of Hefner as a figure, but the ways in which he influenced American culture, for better and worse. The investigation of that impact, however, is fairly strictly limited to the seismic appeal it had for men. When it does discuss the lucrative opportunities it provided for women and people of color, the series creators give them a comparatively meager voice in the film, as analysis is largely offered up by family members and lifelong friends of Hefner’s who work or have worked for Playboy Enterprises.

Also Read

The Crash of the Unicorns

Jesse Jackson crops up sporadically whenever civil rights—an area where Hefner is an categorical hero, according to the doc–along with the late comedian Dick Gregory, in an archival interview. The primary female commenter is Hefner’s first daughter, Christie Ann Hefner, who seems–at least in this film’s edit–unbothered by the absence of her father for most of her early life, as she would go on to become president of Playboy Enterprises in the 1980s. Elsewhere, tributes to Hef comes from charmers like Gene Simmons and Hollywood super-producer/Rush Hour director Brett Ratner, the latter of whom gleefully alludes to the importance Playboy took on in his masturbation routine during his formative years.

You’ll have to wait around five hours in American Playboy to get any real discussion of the dark side of the Playboy empire. Even when the septu-and-octagenarian former executives Victor Lownes and Richard Rosenzweig who began Playboy are telling you that being a Playboy bunny was the best job in the world, it’s hard not to think that there wasn’t a downside to being ogled by hundreds or thousands of men every night as a 18-to-22-year-old woman, no matter how good the tips were. Hefner is, in Playboy’s glory days, never portrayed as anything less than un-gentlemanly; usually, he’s a victim of public opinion. Even when he is shirking his family responsibilities–which began at least in the first moments of Playboy’s existence–he is portrayed as just an obsessive businessman, destined for bigger things, in need of a different, more fluid lifestyle. He and his first wife Millie Williams, by the series’ account, parted on wholly amicable terms, with their relationship becoming simply stagnant rather than emotionally abusive.

American Playboy consistently backs up Hefner’s vision of the ideal American man, even when there are many times when that perspective seems a little limited. If you’re looking for the series to give a picture of Hefner as a legitimately fraught figure, instead of just a blow-by-blow account of the rise and fall of his business empire, you’ll be disappointed. It takes well into the second half of the series for any major obstacles to crop up, as we finally get to the shifting ’70s after eight episodes into a ten episode series. A knottier tale is, I’d venture to guess, what a lot of viewers intrigued by the prospect of this series are looking for. From the opening voiceover of American Playboy, the assumption seems to be that the viewer’s common perception of Hefner is as a “man who [had] it all,” instead of a strange relic of another time, whose towering success now seems increasingly difficult to fathom.