Colin Irwin’s feature on U2‘s album The Joshua Tree first ran in the June 1987 issue of Spin. In honor of the album’s 30th anniversary, we’re republishing it here. Today, U2 announced a set of Joshua Tree anniversary reissues, including “super deluxe” box sets featuring a live recording of the band’s 1987 Madison Square Garden concert, album outtakes and B-sides, a collection of remixes, and an 84-page hardcover book of Mojave Desert photography by The Edge. The package is due out June 2 from Interscope. In May, U2 will kick off a 30th anniversary Joshua Tree tour of North America and Europe.

With a platinum-bound LP and a sell-out tour, U2 have finally conquered America. But first they had to conquer the problem of being a political band in a country torn apart by politics. Dublin’s dockside area is pretty much like dockside areas the world over; you wouldn’t put it high on your after-nightfall sightseeing list. All the same, it’s the part of town that perennially inspires misty-eyed expatriates to stare into the bottom of their pint mugs and reminisce about the enigmatic character of aul’ dirty Dublin. In a city swimming in romance—a historical sense of romance built on patriotism, literary genius, and draught Guinness—the dockside takes on an almost mythical importance.

U2 feel a special empathy for this place. Their studios—Windmill—nestle right in the heart of the docklands. Their business deals are struck and tours set up in the chic offices nearby that act as the central hub of the considerable U2 operation. And they drink in the pub adjacent to the waterfront, on first name terms with the bar staff; they unassumingly discuss the weather, last night’s TV, and other such burning issues with the dock-workers and local characters who frequent the pub.

Whatever happens—whatever happens—U2 always wind up back here. It’s home, of course, but more than that, it’s a sort of therapy. They came back here once, after a particularly triumphant tour of America, imagining that they were the kings of the world, that every right-thinking human being in the Western world was desperate for news of their daily progress. “Oh yeah?” said their mates in the pub, when they bounced in with gushing stories about their adventures, “all very interesting, but are youse gonna get a drink in or what?

It works the other way too. They returned here after playing the Wembley leg of Live Aid in a state of abject depression. They didn’t think they’d played well; they had to chop one song from their set because they’d spent far too long on the first two; and Bono, in particular, felt he’d blown U2’s career entirely when he’d spontaneously leapt into the audience to embrace a young girl. That moment, of course, turned out to be one of the most enduring images of Live Aid, a symbol of the whole event, but they didn’t know it at the time and retired to their lair to lick wounds and decide whether or not they had a future.

So when the regulars in this dockside pub queued up to slap them on the back and say the boys had done OK, something special had happened. When Irish eyes are smiling, they smile like no others.

I had been warned about U2. About Bono. His hospitality. His disarming modesty. His genial, reasoned reaction to criticism. His man-of-the-people persona. Bono, I was told, is a professional nice guy. He seduces interviewers for breakfast. Don’t be fooled, they said, don’t be fooled.

Much of it turns out to be true. As soon as I arrive at U2’s rehearsal studio, he bounds over, all smiles and pumping handshakes, thanking me for coming, offering tea, coffee, or something stronger. It’s an unusual kind of greeting from a guy who could start a riot on the streets of London or New York. Is Bono really that paranoid about preserving his heroic public image?

“If I’m an icon,” he says later, “I must be a very bad icon.” That may be so, but the inescapable suspicion is that U2 have knowingly fueled their near messianic standing. The stark, emotive images they use in their music, the white flag flying symbolically above them on stage, the ritualistic worship from their audience… and that’s before we even think about Bono on stage, lost in his own excitement, crazed and irrational in his boots and blackness, hair flowing behind him as he leaps on P.A. stacks and lands among audiences like a dervish.

Bono grins ruefully at the accusation. He holds up his hand and says, “guilty, guilty, GUILTY.” If it’s any consolation, the rest of the band are equally exasperated by his antics. They’ve sat him down and tried to talk him out of it, fearful that one day he’ll snap a vertebra leaping from a stack or be mauled to death by the pack. I elicit a sort of promise from Bono that this sort of behavior won’t ever happen again. The rest of the band groan when they hear of it. “The thing is,” says The Edge, “Bono just can’t help himself. Have you ever seen him when he comes offstage? He has a kind of glazed look on his face. He can’t help himself. He’s in another world.”

“I always resented being on a stage,” says Bono. “I always resented that barrier between us and the audience, and this led to that infamous gig in Los Angeles where I ended up falling off the balcony and a riot ensued and people could have got hurt. The band took me aside backstage and said, ‘Look, you’re a singer in a band. People in the audience understand the situation… you don’t have to remind them all the time of the fact that U2 aren’t stars to be worshipped. They already know that.’”

Bono’s act of joining the audience was intended as a sign of parity, of oneness; in fact, it always had the opposite effect, suggesting a blessing from the Almighty and provoking more frenzy.

“Yeah, isn’t that funny? I swear to God, that was the last thing on my mind. I came out of the exact opposite feeling. We were born out of that punk rock explosion. I was 16 in 1976 and in a punk band, and this idea of separating the artist from the audience was the antithesis of what the explosion was all about. I carried that with me, and I would end up in the audience as a result. But it was a big mistake. By doing it, it looked like a big star trip. It only happened because… well, we played in England in Milton Keynes in front of 50,000 people. It had been raining all day and the field was like an Irish bog. We went onstage and I thought, ‘How can I possibly live up to this? Are we capable of playing the concert these people deserve? They deserve the best concert of our lives.’ I can’t answer those questions, I can’t come to terms with it. So that sort of feeling has led me to exaggerated gestures onstage, but I’ve since decided words speak louder than actions. I’ve got to write words now and put actions behind me.”

That’s all very well, but while he’s on the stand, we might as well have a go at the songs. Shock for dramatic effect is a useful tool of the songwriter, but U2 have made a fine art of it. Is such liberal use of emotive imagery not a little opportunistic?

“Oh the Irish are great dramatists. The English hoard words and the Irish spend them. We’re loose. Like James Brown… ‘I’m a sex machine….’ Now that’s not subtle. On one level we’re being accused of being too subtle, and on another, we’re not subtle enough. On the new record I’m interested in a lot of primitive symbolism that’s almost biblical. Some people choose to use red and some people choose turquoise. I like red. Some people like lavender. I’ll take Miles Davis home with me, and he paints in purple.

“Sure, we arrived with placards in our hands—and bold placards—but that’s not just what U2’s all about. Boy wasn’t like that, nor was October. It was simply about one album—War—that was a reaction to the new romantic movement, the cocktail-set mentality, and deliberately we stripped our sound to bare bones and knuckles and three capital letters: W, A, R. We stand accused since then for one album. You could say the same thing about John Lennon, he went through a similar period, or Bob Dylan in his earlier work… “Masters of War” and all that. It was just a period we went through.”

Do you regret it now?

“No.”

***

Yet still, there’s a lurking unease. U2 is an Irish band. Which shouldn’t make any difference, but in fact makes a world of difference. Their legacy is Van Morrison, Thin Lizzy, the Undertones, and a host of very fine traditional musicians. But it is also the history of war. The guidelines on this have been pretty clear. Any Irish band with half a chance caught the first available ferry to Liverpool and kept quiet about “the troubles.”

“If you’re writing songs,” says Bono, “there are two things that you just don’t write about—politics and religion. We write about both. No wonder we get into trouble.”

And so U2 created a new mold. They stayed in Dublin, did everything on their own terms, and freely aired their confused state of mind on the forbidden topics. But there was a cost.

“For a few years I didn’t know if I wanted to be in a band at all and we thought U2 might break up,” says Bono. “It was after Boy, which I thought was a great album. I just lost interest. I had less of an interest in being in U2 and more of an interest in other sides of me. Whether I was talking to a Catholic priest in the inner city or a Pentecostal preacher, I was sucking up whatever they had to say. I was interested in that third-dimensional side of me, and I thought rock ‘n’ roll was a bit of a waste of time.

“I thought, OK, U2 were good at being a band, but maybe we could be better at doing other things, like getting involved in the inner city or something. We were teetering on the brink of collapse. So I thought, ‘Well, if I am going to be in a band then I’m gonna write about the things I want to write about.’ Like October is about being caught up with faith, and “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is about hypocrisy.

“Everybody got that song wrong. Probably because I got that song wrong. I was trying to contrast Bloody Sunday with Easter Sunday, to point out that here was a war of religion, which was leading to bloodshed, based upon the dying of one man on a cross. That song has got us into so much trouble, and maybe it was because I didn’t get it right.

“But I was at a point when I almost didn’t care if “Sunday Bloody Sunday” blew up in our faces. Same with October. I just didn’t care. I’ve since worked out that I’m a far better singer and songwriter, with all my failings, than I’d ever be as a social worker or some sort of polemicist. That’s what I’m best at, and I’ve come to terms with this band. I want to be in this band. I think U2’s unique and I think it’s getting better. A lot of our contemporaries are getting worse, but U2’s on the up. We literally started again with Unforgettable Fire. The Joshua Tree is another step, but if people think The Joshua Tree is a peak, they’re wrong.”

Misunderstood or not, the band’s place in Irish folklore is well assured. These days almost every musical project of any significance in Dublin seems to involve or revolve around U2, be it Bono guesting on a hit single by the Donegal folk-pop group Clannad, or the disastrous Self Aid festival last summer, or the flood of new Dublin bands emerging in U2’s wake, many of them sounding like U2 clones, and some of them signed to U2’s own label, Mother.

In a country where half the population is under 25, it has even been suggested that Bono, young, sensible, charismatic, and articulate, should go into politics. For several years Irish politics have been a mess: the national debt is awesome, unemployment frightening, and the leadership keeps shifting between Charles Haughey (who has just regained power) and Garret FitzGerald. As the child of a mixed marriage (his father’s Catholic and his mother, now dead, was Protestant), Bono would, in fact, have a wide non-sectarian appeal. This was apparently well understood by the Vatican, which has recently invited him to meet the Pope. Bono said sure—as long as there was no publicity. “But that’s the whole point!” declared a confused Vatican official. “In that case,” Bono replied, “he can join the queue with the rest of the punters.”

Bono did run into Garret FitzGerald, however, and engaged him in a vigorous argument about unemployment. Later, FitzGerald contacted him and asked him to serve on a committee. Bono agreed, and then pulled out, feeling he was in danger of being used as a political weapon. But the two did meet up again on a social basis. Were they discussing Bono’s political career? “No way. We were talking about T.S. Eliot. We didn’t talk about politics too much. The problem with voting is that no matter who you vote for, the government always gets in.”

***

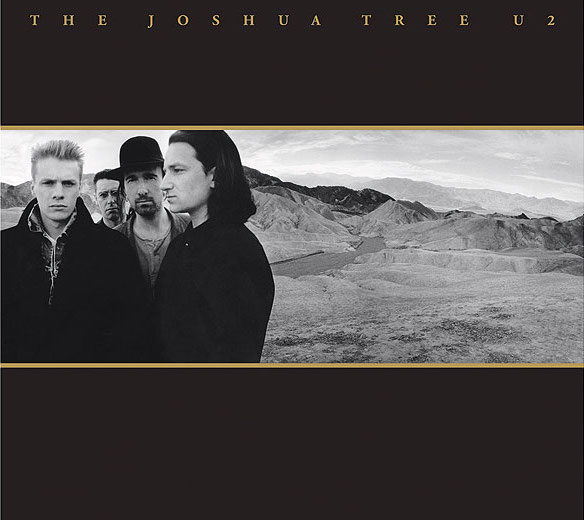

The Joshua tree grows in deserts, an oasis of vegetation in barren lands. It also has religious significance, though Bono is reluctant to explain it. “I’d be walking into a trap if I spelled it out,” he says, grinning. The desert, anyway, is an enduring symbol throughout the album. “A symbol,” says Bono, “of both the positive and negative, the sort of thing you should think about, but not talk about.”

The Joshua Tree is quite different from any previous U2 LP. For one thing, the band wrote songs for it—real songs with beginnings, middles, and endings, with lyrics that weren’t thrown together in the studio between takes. Forever plagued by self-doubt, Bono was wretchedly depressed before its release. At one point, he contemplated calling the pressing plants to stop production because he suddenly had a blind panic that the record wasn’t up to scratch. All doubts have since disappeared: the record has become one of the fastest-selling LPs of all time in Europe, entered the American charts at No. 7, and Bono can almost bear to listen to his own voice at last.

“There’s a side of me I can’t work out. I can’t really work out why anyone would buy a U2 record. When I listen to it I just hear all the mistakes. It’s a shame because we’ve made a few good records. But I just can’t listen to them. Sometimes when we’re on the road, Adam (Clayton) goes through periods where he almost locks himself into a room for a few days and plays the records, and I hear them under his floor, but mostly I think the instrumentation is good or the way the group has played is good. But I don’t like the way I’ve sung on any of the records.

“I don’t think I’m a good singer, but I think I’m getting to be a good singer. On Unforgettable Fire I think something broke in my voice, and it’s continuing to break on The Joshua Tree, but there’s much, much more in there. See, I’m loosening up as a person, about my position in a rock ’n’ roll band, but for years, I really wasn’t sure who I was, or who U2 were, or really if there was a place for us. People say U2 are self-righteous, but if I ever pointed a finger, I pointed it at myself. I was defensive about U2, therefore I was on the attack. When I hear U2 records, I hear my voice, and I hear an uptightness. I don’t hear my real voice.

“A lot of it has to do with writing words on the spot, making them up as I go along. But Chrissie Hynde said to me, ‘If you want to sing the way I think you want to sing and the way you can sing, then write words that you can believe in.’ I’ve never done that. I was literally writing the words as I was doing the vocals. I thought writing words was almost old-fashioned. A hippie thing to do. I thought what I was doing in sketching away way… Iggy Pop had done it and he was a bit of a hero. I thought that as soon as I had a pen in my hand I was dangerous.”

The words he’s written for The Joshua Tree mostly concern America. New musical attitude and the newfound desire to write songs as opposed to sounds led U2 to look beyond the McDonald’s mentality and dig into the roots of American music, of blues and soul and gospel and R&B and country. Bono tells of being amazed at watching Keith Richards at a piano playing gospel music. And when T. Bone Burnett handed Bono a guitar and asked him to casually play a U2 song, he felt he couldn’t do it because The Edge wasn’t around. He determined to find some roots.

“I am one in a long line of Irishmen who have taken the boat or plane to America. At an early age I opened up to America, or America opened up to U2, and I love to be in the U.S. I love the people and the wide open space and the deserts, the mountains, even the cities of America. American people are very open-minded, and there’s a willingness to trust in them that can be manipulated by a man like Ronald Reagan. A dangerous man.

“I didn’t have stars in my eyes, but the time I spent in El Salvador and Nicaragua earlier this year showed me another side of America. The way American foreign policy is affecting the farmworkers of Salvador or Nicaragua was something I felt I had to write about. I suppose The Joshua Tree is about that other side of America. People will accuse of us of biting the hand that feeds, but if that’s the case, then we’ve got to bite it.”

Although the album covers a wide terrain, its key track is perhaps “Bullet the Blue Sky,” a specific reaction to Bono’s recent visit to Central America. “It was awful,” he says. “I wrote the song out of the fear I felt there. San Salvador looks like an ordinary city. You see McDonald’s, you see children with school books, you see what looks like a middle-class environment until you go 25 miles out of the city and see the peasant farmers. I was on my way to a village when troops opened fire above our heads. They were just flexing their muscles. It scared the shit out of me. I literally felt quite sick.”

Bono talks a whole lot more that night in dear dirty Dublin. About U2 fans—they range from Muhammad Ali to Desmond Tutu—his adoration of everything Martin Luther King stood for, and, most urgently, his desire to become a great singer. “My heroes are Van Morrison and Janis Joplin on the one hand, Scott Walker and Elvis Presley on the other. Where I’m at now is trying to work the two together. The other interesting thing is that all the people who inspired me when I was growing up had the same confusions about faith and fear of faith: Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, Patti Smith, Al Green, Marvin Gaye, all of them. This has been a real encouragement. And as a result of being more relaxed about who I am, I’m opening up more….”

He certainly is. Later that night he calls my hotel to make sure I haven’t been mugged on the way back.