This piece originally ran in the February 1999 issue of SPIN. In honor of the 20th anniversary of Built to Spill’s Keep It Like a Secret, we’ve republished this article here.

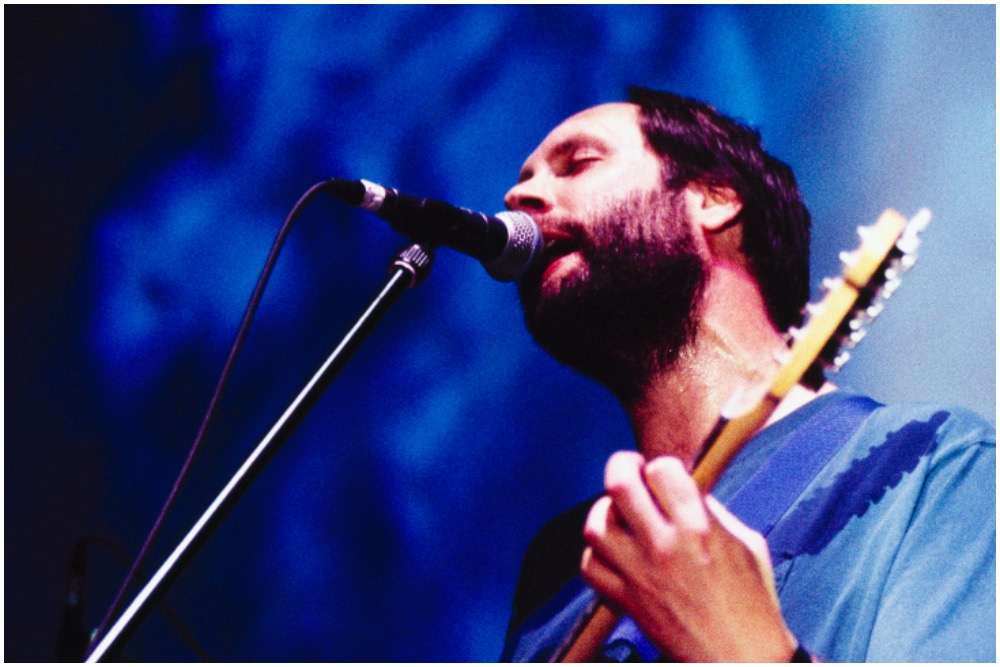

Doug Martsch, the leader of Built to Spill, has this winter coat with a hood and lots of pockets. It was yellow originally, maybe, or light brown, or tan—hard to tell through the stains. The guitarist/singer/songwriter has had it, he says, “eight years or something. I’ve wanted to get a new one for a few years, but I just never shop. Go to thrift stores sometimes, but I never want to look at clothes. My mom sent me a pair of pants recently.” Between his coat and his customary beard, Martsch had been mistaken for a panhandling homeless guy the morning of our interview in tony Princeton, New Jersey. “They almost didn’t let me back into our hotel. This guy was like, ‘What do you want?’ ‘Uh, I need to get in.’ ‘What room are you in?’ ‘Uh, 222.’ He was like, ‘Oh, okay, sorry.’ So if I ever am a street person, I’ll just go ‘222.’ Works every time.” It should be pointed out that the hotel in question is the Best Western off Route 1.

It should also be pointed out that, given the size of the contract Martsch signed with Warner Bros in 1995, after a record-label bidding war for his services, he doesn’t exactly have to live this way. He chooses to, just as he’s chosen to have himself and the other two members of Built to Spill—drummer Scott Plouf and bassist Brett Nelson—do without a roadie and squeeze three into a room (including foldout cot), on a tour that must be earning the band four-figure guarantees each night.

You wouldn’t expect this attitude from, say, Radiohead, arguably the only other late-’90s band to have released a guitar album as majestic as Built to Spill’s last one, the Warners debut Perfect From Now On. But then, you also wouldn’t hear Thom Yorke say, as Martsch does, that he lives so frugally because “we know it’s not going to last. We know we’re not going to make it big.” When Martsch received his signing money, he moved out of the Boise, Idaho, trailer home he was occupying with his girlfriend, Karena Youtz, and their son, Ben (now almost five), into a real house with a home studio in back. With the money left over from what Warners gave him to record Built to Spill’s new album, Keep It Like a Secret, he’ll pay off the house and still have enough to send Ben to an alternative private school. His rock ‘n’ roll dream, such as it is, has already come true.

Even by the standards of the indie rock scene he emerged from, Martsch’s park-ranger looks and utter lack of attitude make him a strange duck; for a guy on a major label, he’s otherworldly. Self-effacing to an extent that slights his very real talents, bright-eyed, open but wary, Martsch finds standard biz schmooze overwhelming, and the idea of selling his talents unbearable.

For instance, there’s this pop music tradition: Concerts should include songs from your latest album. Shows you like the thing. Not Martsch, who gave Warners Perfect From Now On, a gorgeously textured piece of orchestral punk whose tracks average seven minutes (forget radio crossover), then bad-mouthed the CD in interviews and played exactly a song and a half from it when he toured in the summer of 1997. On this current road jaunt (he only goes out sporadically, so as not to miss time with his son), Martsch is performing a grand total of three songs from Secret; he’s still only attempting a couple from Perfect.

True Built to Spill fans aren’t complaining. The concerts remain as musically satisfying as those of any rock band out there, proof of a major talent that needn’t be summed up by a single release. Martsch draws from a catalog that’s voluminous for a guy still a year shy of 30: three albums with Treepeople, his caterwauling first band formed during the brief period he lived in Seattle (he left as grunge was hitting big, returning to Boise to be with Karena); three more with the Halo Benders, a pairing with Beat Happening frontman and K Records guru Calvin Johnson; and six with Built to Spill, including a rarities compilation and a Caustic Resin collaboration.

In any guise, Martsch’s music willfully mixes up the simple and complex: His epics feel like throwaways and his throwaways feel epic as he moves affably among stoner-rock largesse, slightly skanking punk rock insistence, surreally naive pop tunes, and songs that run through more chords and subsections than most indie bands manage in a lifetime. And though Built to Spill play the exact same set each night, Martsch radically reworks the songs from the records; at a Hoboken, New Jersey, show, two bootleggers pleasantly argued over who would get to tape the set off the sound board.

Bassist Nelson, a fellow Idahoan, has known Martsch since junior high, when they used to argue metal versus New Wave (Martsch was the Scorpions fan). “Doug’s got the same haircut as when I met him,” Nelson marvels. “The only difference is his beard. He never was exactly fashionable for music.” By high school, the two discovered punk and were forever changed. Martsch’s nuclear family, oddly, all converted to Catholicism; the creed Martsch took for his own was purebred Amerindie, not, he’ll tell you, the more stereotypical Sex Pistols rebellion. “It wasn’t about smashing shit up,” he says. “It was about doing cool things, people who were open-minded. That was my romantic image of it. Of course I found out otherwise about lots of people involved. But there is something there that I still hold sacred. Even if it’s an illusion.”

Punk’s ideal of self-reliance goes beyond music for Martsch, who says he bonded with K’s Calvin Johnson over the radical theorist Noam Chomsky, and of late has been reading populist historian Howard Zinn. Besides living simply, Martsch is aggressively localist in his affinities: always taking Northwest indie bands such as Modest Mouse and Satisfact on tour with him; even ending one series of concerts with a jam on “Lie for a Lie” that featured the opening group taking over the instruments Built to Spill had been playing, a passing of the torch. “Doug’s a good influence,” says Satisfact’s Matt Steinke. “A friend of mine says talking to him is like talking to an angel.” Appearing as guest DJ on the college radio station in Princeton, Martsch searches the bin for fellow regionalists such as the Feelings and Elevator to Hell, rejecting Elliott Smith, whom he admires, because “everybody knows about him.”

But will more than the zealous handful who love his mind games and guitar splashes ever know about Doug Martsch? Keep It Like a Secret is more accessible than Perfect, with shorter songs and an anthem of sorts, “You Were Right,” which regurgitates with Classic Rock clichés ad nauseam: “You were right when you said a hard rain’s gonna fall”; “You were right when you said we’re running against the wind.” His A&R man at Warner Bros., Joe McEwen, remains optimistic. “I think he has the ability to write great pop songs—he’s so close,” says McElwen. But whether Martsch wants to get any closer is another question. “When I think about our audience,” he says with his usual cheery reserve, “I think about my friends, you know?” And if that’s not enough? Another big smile. “Oh, we-ell.” Does the current unpopularity of guitar rock discourage him? “In a way that depresses me, but in a way it’s what we’ve been shooting for all along.”

Warner Bros. is contractually required to release one more Built to Spill album, and if sales don’t climb beyond the last album’s 43,000, that’ll likely be it. But major label or no, Martsch won’t stop handcrafting his sound, or showing a determination he refuses to trumpet. At Princeton, Built to Spill headlines Bucks for Fucks, a university eating club party at which attendees dress as prostitutes or pimps. Nelson says at dinner beforehand that he feels like one of the poor kids in a John Hughes film. But the group rocks just as aggressively as they had the night before at the Hoboken indie rock sanctuary Maxwell’s; when Nelson breaks a bass string 19 songs in, after 2 A.M., in front of a visibly thinning crowd (it’s midterm week), Martsch and Plouf jam till he fixes it, then plow through their final two numbers. A week later, at an industry event for the CMJ music showcase, they were no better, no worse. These guys are committed, in a noncommittal sort of way.

Following the showcase, Built to Spill play unannounced at a K Records event (they’ll do the same for indie Up the next day), trowing in a cover of Steve Miller’s “Take the Money and Run”: Get it? Occasional Halo Bender Heather Dunn bangs tambourine and supplies Dada backing vocals, Calvin Johnson does his belly flop, and on the triumphantly swirling “Virginia Reel Round the Fountain” a crowd of K folk swarm onto the stage. Magically, Doug Martsch has managed to have it both ways, banking Warner Bros. bucks while remaining contentedly indie. Surrounded by his people, Martsch looks as happy as I’ve seen him, welcomed back into the tribe without so much as a joke about the prodigal son.