For a rock icon of the ’60s and ’70s, Neil Young has had an awfully long, awfully strange career—he was famously sued by his own label for not sounding enough like himself on an album from the mid ’80s—and delving into his music can consequently seem like a daunting task. But now that Young is back on Spotify and Apple Music, anyone who’s been putting off the task of digging into his insanely deep catalog no longer has any excuses.

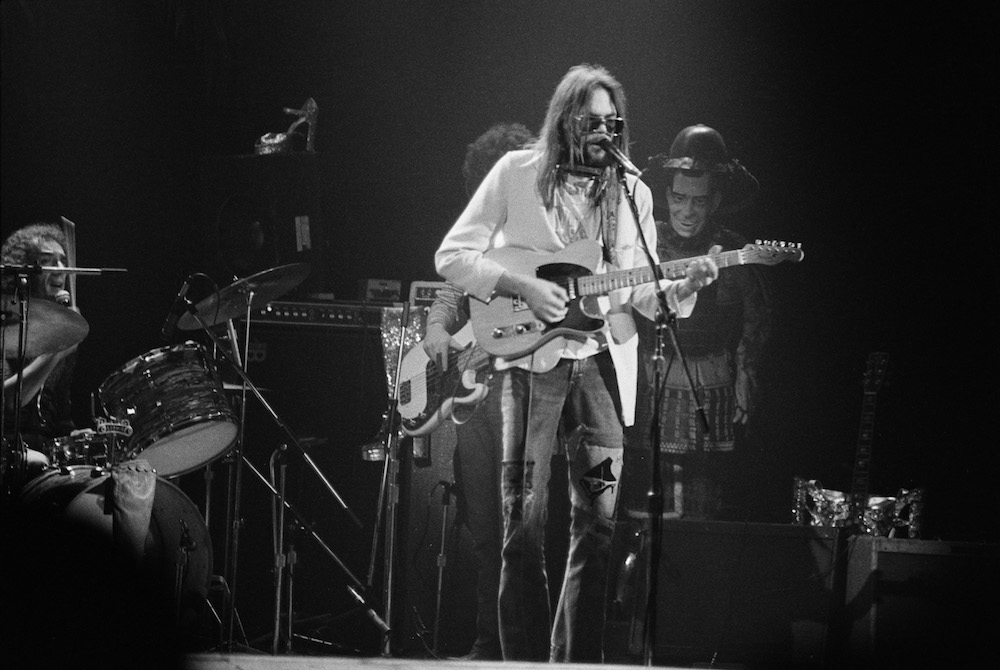

You’d have a hard time finding so much as a single bum note in the dozen-plus albums Young released during the first decade of his solo career, so one option would be to just pick an album between his 1969 self-titled debut and the 1979 tour document Live Rust and press play. But if you’d like a more guided tour than that, below you’ll find 10 great songs, each of which offers a slightly different path. We’ve mostly stayed away from the big hits here, focusing instead on lesser-known tunes that exemplify something special about Young’s sweeping vision of rock’n’roll, encompassing the mellowest California folk, the fuzzy jams of his longtime band Crazy Horse, and his far-out experiments in electronic alienation.

“Motion Pictures,” On the Beach, 1974

On the Beach is perhaps the most beloved album among die-hard Neil fans. It came second in his so-called “Ditch trilogy” of the early and mid ’70s, a trio of challenging and often dark albums that came after the runaway success of 1972’s Harvest, at a time when listeners mostly thought of Young as a free-spirited folkie with an occasional taste for long guitar solos. Among visions of oil-sucking vampires and mass-murdering revolutionaries storming Laurel Canyon, there’s “Motion Pictures,” one of the sparest and loveliest ballads Young has ever recorded. “I hear the mountains are doing fine,” he sings, backed by a wistful lead guitar. The world may be full of blood and confusion, but while “Motion Pictures” plays, everything is all right.

“Powderfinger,” Rust Never Sleeps, 1979

Never mind the songs—simply sorting your way through the bands Neil Young has played with over the years can be a challenge. There are the solo records; the contributions to Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young; the Stray Gators, who backed him during the Harvest years; the brief flirtation with Devo. Easily the most important of these groups is Crazy Horse, the muscular rock band that first backed Young on his classic second album, 1969’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and continued working with him, on and off, on more than a dozen albums spanning his entire career. For a one-song encapsulation of the Crazy Horse sound, try the anthemic “Powderfinger,” which first appeared on the ’79 live album Rust Never Sleeps. Close your eyes and you can almost imagine you’re hearing the Men or Dinosaur Jr.

“Lotta Love,” Comes a Time, 1978

“Lotta Love” was a top-10 pop hit single in 1978, but only after Nicolette Larson, who sang backup on Comes a Time, recorded her own discofied cover version. Comes a Time is sort of a spiritual sequel to Harvest, Young’s folk-rock breakout album, and with its cascading vocal layers and irresistible chorus, “Lotta Love” is very much in that wheelhouse. It also shows that—despite the grit and feedback of his rangier work—Young was always capable of writing a perfect pop tune.

“Down by the River,” Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, 1977

I know, I know: “Down by the River” is not exactly a deep cut. But no song that nears the 10-minute mark can be dismissed as a fluffy single, even if everyone you know can sing along to the chorus. Young’s lacerating electric guitar playing is an underappreciated facet of his genius, and there’s no better showcase for it than the middle section of “Down by the River.” Dueling with the late Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten, Young lays down what is, for my money, the greatest rock guitar solo ever played, favoring swaggering rhythm over the flashy pyrotechnics he was more than capable of unleashing. Each note is like the slash of a knife, cutting you down as you listen.

“Winterlong,” Decade, 1977

New songs recorded for greatest-hits compilations are usually throwaways, but not “Winterlong,” whose aching melody first appeared on the 1977 compilation Decade (another pretty good place to start for Young neophytes, incidentally). Neil Young’s influence on grunge and the shaggy indie rock of the late ’80s and ’90s is immeasurable. For evidence of that, witness the ’95 Neil album Mirror Ball, which saw Pearl Jam playing backing band for their hero, or Sonic Youth’s stint opening for him on tour in ’91, or the Pixies’ loving version of “Winterlong,” released as the B-side to 1990’s “Dig For Fire.”

“Driftin’ Back,” Psychedelic Pill, 2012

Among Neil Young’s many idiosyncrasies is his fanaticism with audio sound quality. The whole reason his music disappeared from Spotify in the first place was the Pono, a piece of hardware and proprietary file format, conceived of and marketed by Young, that supposedly played back music at a higher definition than was available on other portable players. Whether or not you share his ideas about clarity, you’ve gotta respect it. Halfway through his half-hour guitar epic “Driftin’ Back,” from 2012’s Psychedelic Pill, after about 10 minutes of free associations about Picasso, Jesus, and the Maharishi, Young delivers a chant that is always a hilarious surprise, no matter how many times you’ve heard it: “Don’t want my mp3, don’t want my mp3.” The man was 67 years old at the time, and this was the first song on the album. Neil Young has his convictions, and he does not back down from them.

“Thrasher,” Rust Never Sleeps, 2010

Young isn’t really known for his lyrics, which are sometimes hectoring or sentimental. But on the acoustic ballad “Thrasher,” he’s remarkably vivid, watching farm equipment slowly rolling toward an unspoiled field, burning his credit card for fuel. “Where the eagle glides ascending, there’s an ancient river bending / Down the timeless gorge of changes, where sleeplessness awaits,” he sings in the second verse. “I searched out my companions, who were lost in crystal canyons / When the aimless blade of science slashed the pearly gates.”

“Mr. Soul,” Trans, 1982

In a catalog filled with left turns, Trans stands out as perhaps the weirdest Neil Young album. Recorded in the midst of what was evidently the world’s greatest Kraftwerk binge, Trans finds Young’s voice fed through an icy vocoder on six of its nine songs, backed by stiff drum machines and synth patches. This wasn’t alienation for alienation’s sake: The far-off nature of the vocals was inspired by Young’s attempts to communicate with his young son Ben, who was born with severe cerebral palsy and had difficulty speaking.

“At that time [Ben] was simply trying to find a way to talk, to communicate with other people,” Young said in a 1995 interview with Mojo. “That’s what Trans is all about. And that’s why, on that record, you know I’m saying something but you can’t understand what it is. Well, that’s the exact same feeling I was getting from my son.” “Mr. Soul,” a rerecording of Young’s 1967 hit for Buffalo Springfield, offered longtime fans a familiar tune to grasp amid the new electronic sounds.

“Arc,” Arc, 1991

The only Neil Young record that can hold a candle to Trans in terms of audacity is Arc, a 1991 “live album” that featured a single 35-minute track, collaged together from bits of crowd noise, feedback, and song fragments recorded during Young’s ’91 tour with Sonic Youth. The cut-and-paste style was apparently based in part on a suggestion from Thurston Moore, and like Sonic Youth, the album mixes pure noise with moments of bracing rock. Arc is no easy listen, but it’s a lot more fun and accessible than its reputation might have you believe.

“Girl From North Country,” A Letter Home, 2014

Old age has not dulled Young’s adventurous impulses in the slightest. In 2014, he sat down in Jack White’s 1947 Voice-o-Graph recording booth, which cuts straight to vinyl, and recorded A Letter Home, an album of covers, paying homage to Bruce Springsteen, Willie Nelson, and others. Bob Dylan’s “Girl From North Country” is an obvious highlight, the Voice-o-Graph’s old-fashioned grit matching the nostalgia of the lyrics. But A Letter Home‘s true heartbreaker is its spoken introduction.

“It’s great to be able to talk to you. I haven’t been able to talk to you in a really long time,” Young says into the antique microphone, addressing his mother, who died 15 years earlier. “My friend Jack has got this box that I can talk to you from. I’m glad to be able to send you this message, and tell you how much I love you, and also tell you that I think you should start talking to daddy again. Since you’re both there together, there’s no reason not to talk.” After that, he starts playing.