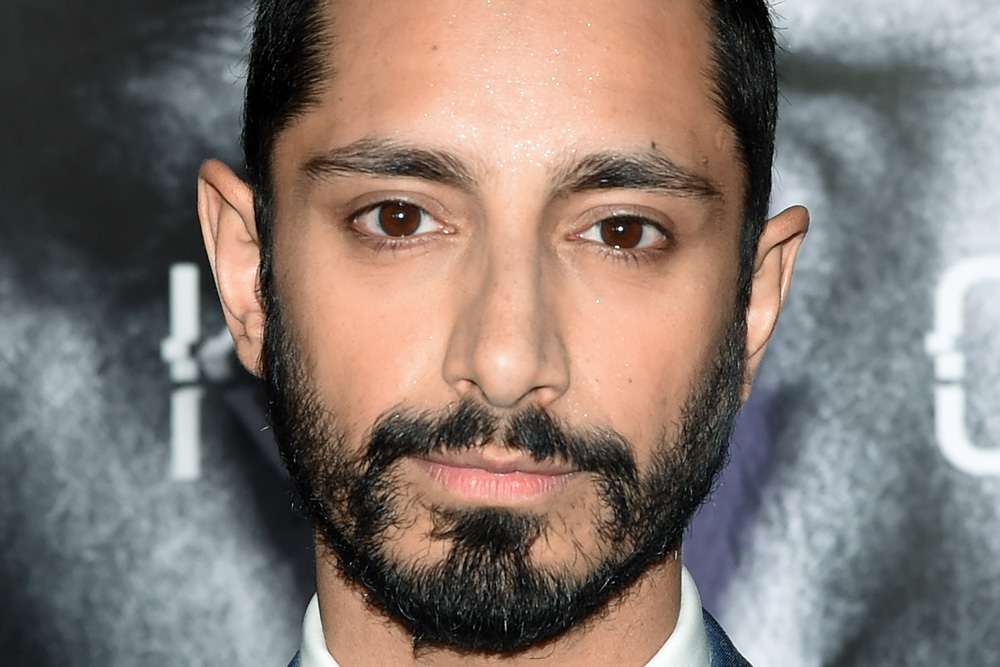

Riz Ahmed might be having the busiest year of his life. Not only does the U.K.-born actor and musician have the lead role on HBO’s critically celebrated crime drama The Night Of, but he’s booked a ton of film roles in 2016 alone, playing a social-media CEO in the latest Jason Bourne installment, a private eye in the forthcoming mystery City of Tiny Lights, and a former Imperial pilot in December’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, just to name a few.

In addition to his high-profile acting gigs, Ahmed is also a rapper who performs as Riz MC — this October he’s due to release an LP with former Das Racist MC Heems under the joint moniker of Swet Shop Boys. One could assume that Ahmed would end up more invested in one venture than the other, but the 33-year-old pursues both music and acting with equal zeal. “Sometimes one thing can open doors to the other,” he explains over the phone. “My first track, ‘Post 9/11 Blues,’ got banned [from British airplay]. Chris Morris, who directed Four Lions [a 2010 film in which Ahmed starred], saw that video and he reached out to me. We started a conversation and a collaboration over three years, which led to Four Lions.”

But for the time being, Ahmed’s most visible role is on The Night Of, where he plays the once-doe-eyed — but later tatted-up and drug-smuggling — prison inmate named Nasir Khan, a young Pakistani-American college student accused of murdering a woman after an inebriated evening spent at her Upper West Side apartment. We speak to Ahmed about his HBO performance below, as well as his musical inspirations, and the time he scored a front-row seat to Michael Jackson’s Dangerous stop at Wembley Stadium.

What drew you to the role of Nasir Khan on The Night Of?

I think it’s just really interesting to read well-written characters. Naz doesn’t necessarily have the most dialogue, but it doesn’t matter because it’s a part of a project where all of the characters are written well. You can read a character that feels amazing, but if the world around it and all the writing around it — even the way the stage descriptions are written — don’t feel just right, then you know there’s no point in doing the project. No character is ever bigger than the whole film.

Did you seek this project out, or did HBO seek you out?

No, I didn’t know anything about it. I’m from the U.K. — we don’t have HBO there. In 2011 or 2012, I was coming back from Venice Film Festival off The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and my agent called me and said, “I’ve sent you a script. Read it on the plane. You’ve got an audition when you land.” I didn’t know who [series creators] Steve Zaillian or Richard Price were. I just read the script and thought, “Wow, this is cool.” Literally went in the room, dropped off my bags, went into town, and read two scenes. I think sometimes things work out better if you’re not in control of them. You don’t have time to overthink.

So they definitely envisioned the lead role being of Pakistani descent?

Yeah, absolutely. I think Steve and Richard are both sticklers for authenticity. So something that they felt was important was that in the British version [Ed.’s note: The Night Of is based on a British series called Criminal Justice] it was the son of a cab driver, and they kept that element. Cab drivers in New York are not going to be white caucasians, generally. They’re going to be South Asian, Middle Eastern, West African. So [the writers] just went, “Okay, so [the lead] obviously has to be Pakistani.” And when you put that domino down, suddenly it takes you into this whole other world and opens up this community and these issues of xenophobia. But I don’t think they ever went into it saying, “Okay, we want to talk about this issue or theme.” It’s about just really putting a magnifying glass on the world around us and seeing what follows from that.

I know that James Gandolfini was involved in The Night Of before he passed away. Did you have the opportunity to meet him during filming of the pilot?

James was on board from the beginning as an executive producer. He was going to play the character of John Stone. In episode one, John Stone’s character is not in most of the episode. So the amount that he actually ended up filming with the pilot was actually quite minimal. I think we shot that pilot in 2012, during Hurricane Sandy. I remember that crane that came loose in Manhattan, it was dangling over our hotel. I remember that we had to be evacuated, myself and Peyman [Moaadi], who plays my father, and Poorna [Jagannathan], who plays my mother. The next day we came into work and I remember James was talking about the hurricane and stuff. He was just such a down-to-earth, chilled-out, generous guy. I remember he laid on, like, sushi chefs and pastry chefs for the crew as a treat the day that he was filming. He seemed to be that kind of guy — very generous spirit.

Naz — and, by extension, his family — undergoes a series of life-altering changes as he tries to prove his innocence. Even if he does ultimately walk free, will he ever fully regain the life he had prior to the murder he’s been accused of?

Speaking in generalities, the legal system, the criminal-justice system, any kind of system is essentially kind of dehumanizing and it can harden you or it can break you down. Often it does a combination of both of those things. I’ve interviewed lots of different people who’ve been through the prison system, and it had different effects on different individuals, but it was life-changing for all of them. It’s a lot like being in war. It’s something that stays with you.

Being from the U.K., what did you learn about the American legal system that you were perhaps less aware of before?

Something that was interesting is just the concept of Rikers Island. Whether you’ve been accused of murder or shoplifting [in New York City], you’re going to probably end up in Rikers. If you don’t have proper legal representation and you can’t make bail, you get sent to central booking, which is weird that it’s right underneath New York City — under Chinatown. This subterranean labyrinth of holding cells, and then from there if you don’t make bail, or they don’t grant you bail, or you can’t afford bail, or you don’t have the right lawyer to ask for bail, you’re going to go to Rikers. It’s this real mix of people from across the whole spectrum of the criminal-justice system. People can be stuck their for years.

As Naz’s story develops, he consistently faces — both in and out of prison — being reduced to a cultural stereotype. Are you interested in raising awareness in terms of the roles you play in your acting career?

No, I mean, I don’t see myself as an activist or anything like that. I think that denigrates the real effort and commitment of true activists who do the real work. Ultimately, as an actor I want to play a diverse range of roles. But [because] of the time and place I was born and the body I have been brought into, playing characters and appearing on TV screens in itself feels like a political act. I think that’s a gift and a curse in some ways.

I think it’s funny that we apply the label of “political” to a certain kind of art or certain kinds of artists more regularly than we do to others. I think ultimately what’s going on there is people who don’t necessarily fit the traditional mainstream mold, or whose work is focused on people that may not be as visible in our culture, get labeled as political. Well, ultimately all of it is political.

Switching gears for a second, what’d you grow up listening to?

I grew up listening to a lot of early ’90s hip-hop. I had the debut Wu-Tang album, Biggie, Snoop, that kind of stuff. Hieroglyphics, the Gravediggaz. I remember D.O.C.’s The Portrait of a Masterpiece was something that had a big influence on me. The athleticism of that kind of rapping, where you’re rapping really fast — that was something that applied to me as a kid.

Growing up in the mid-to-late ’90s in London, you start seeing the explosion of drum’n’bass and then the birth of U.K. garage and grime. I decided to focus a lot of my energies as an aspiring MC. It was a very natural way to express yourself as a kid from a certain kind of neighborhood. At the time, we were surrounded by pirate radio stations — before the internet blew up. I would do sets on pirate radio as an MC. As much as I enjoyed the pace of double-time flows and syncopated rhythms, my inspiration for lyrical content came from the U.S. — Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Common were big influences on me.

What informs the music you make as Riz MC?

I get good references from a wide range of music. Something who’s been a good influence in the last few years is Qawwali music. If you listen to a Qawwali singer like Aziz Mian — he’s like James Brown. Qawwali is like Pakistani gospel-jazz. It’s emotional but it’s also improvised, and it’s all about that sacred-and-profane tightrope. He’s dropping punchlines. Growing up, my role models, particularly as a rapper and stuff, were all black, and that was something that I really embraced. People like Tupac. But it was interesting to, in the last few years, find a lineage of singing and storytelling and rhyming that comes from my own ethnicity.

Do you remember the first CD or cassette you ever bought?

It was “Don’t Walk Away” by Jade. [Sings] “Don’t walk away boy / Don’t walk away / My love won’t…” The first album I bought was Diamonds and Pearls by Prince and the New Power Generation. The reason I bought it was because of the track “Get Off.” I saw the music video, and it was the most sexy, arousing thing I had ever seen as a 12-year-old.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=RAsgeSp2PjI

And what about your first concert?

I remember when I was 10 or 11, Michael Jackson was playing at Wembley Stadium. I think it was the Dangerous tour. My brother managed to get a ticket to go with some friends. I couldn’t go, and I was crying my eyes out because Michael Jackson was my absolute hero. So my dad randomly gets a phone call from a family friend who goes, “We’ve got one extra ticket.” So my dad took me to Wembley Stadium. I can’t believe he did this — he went up to a random South Asian family who were also in the line and just left me with them. He said, “Look, this is my son. He loves Michael Jackson. He has a ticket. Son, go with them. Will you take care of my son for the concert?” And they were like, “Um, okay.”

They went to sit all the way at the back, and I was like, “I’m just going to the toilet.” And I just left. I went in between people’s legs so I could be right near the front. I stood on a random box that someone had left in the crowd so I could see everything. It was just incredible, man.

By the end of the concert, I was like, “S**t, these people are going to be looking for me.” Against all odds, walking back through exciting I just bumped into them. They were like, “You totally ran off.” I was like, “Shhh, don’t tell my dad.”