In honor of the recent 20th anniversary of Jay Z’s debut album, Reasonable Doubt, we’re publishing a series of pieces looking at the rapper’s singular career and achievements. Welcome to Jay Z Week.

Jay Z is Top Five, Dead or Alive by default not only because is he a gifted lyricist, incomparable hitmaker, and New York hip-hop ambassador. No, Jay Z’s place in the canon comes from the fact that Shawn Carter embodies a lifestyle. His body of work and biography — the real-life story of a doomed drug dealer who becomes a legitimate businessman and, later, a business, man — has helped shaped an entire culture’s weltanschauung. But back in the mid-’90s, Jay Z was just another guy trying to get signed.

Hov had already proven himself before his debut, Reasonable Doubt, dropped on June 25, 1996: His demos were classics, he spit rhymes at ridiculous speeds, and he had a co-sign from legendary OG Big Daddy Kane. Still, DJ Clark Kent, formerly an A&R at Atlantic, couldn’t convince executives that the artist then known as Jaÿ-Z was a bankable star. He saw what Jigga was capable of during those pre-Doubt days and his frustration boiled: “For a while I was like, ‘F**k all A&Rs,’ because I was like, ‘I tried to show you this s**t.’ Like, ‘What makes you not see this?'”

After a deal with Payday Records fell through, Jay Z pooled his money with fellow entrepreneurs Dame Dash and Kareem “Biggs” Burke to form Roc-a-Fella records and finally release his hustler’s bible, Reasonable Doubt, which went on to become a new standard for East Coast street rap. A skillfully woven tale of crime and glamour, the album remains a grand accomplishment, especially considering its relatively small-scale ambitions: Jay Z and his talented team just wanted to prove they were the best in the game. They weren’t planning to continuously shift the culture for two decades, or lay the groundwork for a hip-hop empire. They weren’t even planning to release a follow-up.

“I think that’s the reason why it was so good, because it was more, like, effortless,” DJ Clark Kent says. “‘Yeah, we gon’ do it. We gon’ put this record out and we gon’ walk away.’ That’s what the plan was.”

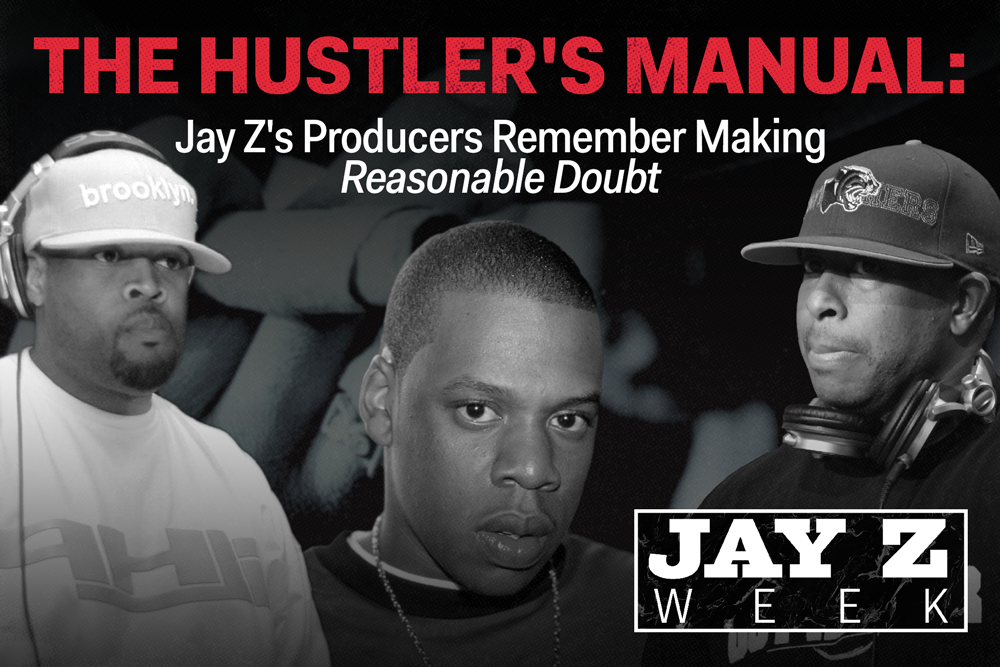

Jay Z couldn’t leave the game alone, though. Roc-a-Fella rose to dominance at the turn of the century before falling apart in 2004; Jay Z, Dame Dash, and mentor Jaz-O eventually went their separate ways; and the King of Rap scepter currently belongs to the North. But Reasonable Doubt‘s classic status remains unimpeachable. The beats are still as crisp as they were two decades ago, and the lyrical gems — universal truths about perseverance, camaraderie, and confidence, all derived from street realities — are still precious. To celebrate the album’s 20th anniversary, SPIN spoke with several of the producers behind Reasonable Doubt (including DJ Premier, DJ Clark Kent, and Ski) about the crate-digging excavations, convenient twists of fate, and exchanges of cold, hard cash that went into the album’s creation. Don’t knock the hustle.

https://open.spotify.com/embed/album/3YPK0bNOuayhmSrs0sIIBR

Prelude

Ski: Well, DJ Clark Kent introduced Jay Z to Dame Dash and myself. Back in the ’90s, Clark was producing Jay Z, and Jay Z was looking for management. At the same time, Dame was managing a rap group I was in, going by the name Original Flavor. Clark brought Jay to one of our video shoots and Jay kind of auditioned for Dame, and what Dame heard was too hard. He knew [Jay] was the truth.

When he did the “Can I Get Open” record, that was him showing and proving right there. He wasn’t rhyming about his life per se in that song. And that happened later, when I think one of his friends pulled him to the side and was like, “Yo dude, you living this life, man, that people don’t really know about. You need to take your rhyme abilities and talk about what you really do.” That’s when Reasonable Doubt became Reasonable Doubt.

DJ Premier: I knew Jay already because of Jaz-O and him already doing the [1989] “Hawaiian Sophie” record. Jay just did a few lines on it. I used to see them together a lot at all the hot hip-hop spots we would hang at around that time — back then it was [New York nightclubs like] the Payday, Milky Way, and Mars. Those were the hip-hop spots where, if you weren’t really popular, you couldn’t even get in because they were selective with who they let in. I remember Jay Z coming in with that giant chain. He really had a big, long chain on even back then.

DJ Clark Kent: I don’t think there was ever a moment when he wasn’t making Reasonable Doubt. I think the first time he made a demo it was to make Reasonable Doubt.

“Can’t Knock the Hustle” (feat. Mary J. Blige) [Produced by Sean C, Dahoud Darien, and Knobody]

Sean C: [Knobody, Dahoud Darien, and I] would always be at Knobody’s house — his mama’s house [in Harlem]. She would let us be in there making beats all day.

We knew who Dame was and we knew he was working with this new rapper, Jay Z, who was starting to pop. So we were like, “Yo, let’s give him some beats.” We gave him a beat tape that had a bunch of beats on it and “Can’t Knock the Hustle” was one of them. And I remember he hit me up saying, “Jay wants to use this one.”

Knobody: I sat there and developed a whole track there in the house and then introduced the track to everyone. It wasn’t until Jay Z got on it that I had Dahoud come in and add some chords and sounds to it. And the same goes for Sean. But the original track was done with me. It basically was just playing over the sounds that were in the track — to thicken it up.

Dame told me [Blige] was crazy over the track itself, so that was pretty amazing to hear at that time in my career and from an artist like Mary. It was an honor, to be honest.

Dahoud Darien: I mean [Jay Z] sat up there, listened to the beat. He don’t write no rhymes down, no paper. Just like they say Biggie do it, he do it the same way. He’ll sit up there in the corner while he’s playing the beat. He’s sitting there, nodding his head for a little bit. I remember you think he’s listening to the beat but he’s probably just writing the rhymes in his head at the same time. And then he goes into the vocal booth and knocks it out like a champ.

[The beat] was a replay of Marcus Miller. And, musically, think about “Lifestyle” with Young Thug. If you think about it, they were heavily influenced by that record just because, boom boom boom, and the other goes, boom boom bo boom. You can’t knock the hustle, you dig what I’m saying?

I remember in the beginning when Jay Z did his vocals, they had like a ’round the way girl who was on it. I remember specifically saying, “Okay this is not it. We’re going to have to back and get somebody else.” Knobody ended up telling Dash, “Yo, we gotta change the hook around on the vocals.” Then Dash was like, “You know what I’ma do? I’ma get Mary J Blige.” And that’s what happened.

“Politics as Usual” [Produced by Ski]

Ski: I was in Long Island with my son’s mom, driving back from the mall. Turned the oldies station on, ’cause I always listen to the oldies station, ’cause you know I was a [crate-]digger. I’m listening to the radio and motherf**kin’ Stylistics come on: “Hurry Up This Way Again.” I just kept listening to the radio, saying, “That would be kinda tight.” So she took me to the record store. Copped the CD. Went home, assembled it, chopped it up. I said, “Yeah, Jay. It’s crazy.”

Rumor has it that Clark Kent made a version of the same beat, but Jay took my beat. Clark tried to tell me that his beat was better. I was like, “Nigga, if your beat was better he woulda took your beat.”

“Brooklyn’s Finest” (feat. The Notorious B.I.G.) [Produced by DJ Clark Kent]

DJ Clark Kent: What happened was [Biggie finally] had competition. Because Big was out, he s**t on everything. You know, Nas was who he was and he was doing what he was doing, but this guy was different. So Nas is kinda the s**t and Big kinda s**t, but Nas isn’t his direct competition. This guy Hov comes and it’s like, “Hold up.” And I’m warning [Biggie] like, “My guy is coming… He don’t write rhymes.” “Get the f**k outta here.” I’m like, “No, he don’t write rhymes. He usually gets it in one take. He ain’t gotta do his verses over.”

Right before I went to the studio, I was in a session with Biggie and Junior M.A.F.I.A. [The beat for “Brooklyn’s Finest”] played by accident and Biggie wanted it for himself. I told him it was for Jay and he was mad. He liked it so much that he was like, “Nah, I gotta be on the song.” So I said, “Just come to the studio.”

I left him in the car and I went upstairs to record with Jay — never said nothing until he comes out the booth and the record’s done. And I say, “Yo, we should put Biggie on this,” and he’s looking at me like, “What are you talking about?” And Dame is like, “Nah, ’cause we ain’t paying Puff no money.” All that. I was like, “Well, you know he’s my man.”

So I acted like I had to go to the bathroom, went downstairs, brought him back up. [Jay Z] was like, “You a funny nigga,” but that happened. They became friends instantly. That’s because of the respect they had for each other’s art.

The [sampled] song itself [Ohio Players’ “Ecstasy”] is my favorite record — ever. And I liked it since it came out [in 1973] when I was a kid. And as I became a producer, I always wanted to try to use it. So I used it once before, on a song by a group called the Future Sound, which was one of Damon’s artists. I didn’t feel like I used it right, but it was still my favorite record. Every party I played, at the end of the night, I played that song.

They wouldn’t do a hook and I didn’t wanna do it, but it was, like, eight hours going by and we had nothing. I was calling them like, “Can y’all come back to the studio?” Ah, scratch something. I could scratch everything, but it’s not coming out right because the beat had a certain feel to it. So I just I looked to the second verse and it said both of their names. I just wrote around that and was just like, “Let me see if I can come up with something.”

I think what made it easier was when I left that space and shouted out cities in Brooklyn. I just wrote down, like, every little section of Brooklyn and said them until I ran out of space to say. So it was Marcy, Bed-Stuy — which was kind of stupid because Marcy [Projects are] in Bed-Stuy. But I didn’t care. I wanted both of them to have their section. I wanted to it to be Marcy equals Jay, Bed-Stuy equals Big.

“Dead Presidents II” [Produced by Ski]

Ski: The first beat I made for Reasonable Doubt was probably “Dead Presidents.”

I have no idea [why “Dead Presidents II” appeared on Reasonable Doubt instead of the original]. I never knew. Maybe he wanted to give the people more. Maybe he wanted to say, “F**k it, let’s switch it up and give ’em a little bonus verse.” You never know.

We went to this music conference — I think it was How Can I Be Down? Nas had just released Illmatic and he had the song on there, “The World is Yours.” And I was playing that song the whole time I was there. I couldn’t believe what [Pete Rock] did with the beat and how the piano was so melodic. So I said, “You know what? F**k that. When I go home, I’ma try to find something that sounds like that.” So I was digging and digging and digging. Then I came across the Lonnie Liston Smith joint and I said, “Ah yeah, this s**t right here? I feel this.” I added the drums, then I took the Nas sample just to reference it.

I played it for Jay and then the Nas hook came on and I said, “Don’t worry about that, I’ma take that out.” He was like, “Nah, keep that. That s**t is dope.” So that’s how we ended up keeping the whole Nas sample in there.

When he laid that [verse] down the first time, I was like, “F**k is wrong with you? How you saying this kind of s**t?” I was just happy that this crazy-nice nigga was on my beat.

“Feelin’ It” (feat. Mecca) [Produced by Ski]

Ski: “Feelin’ It” was actually like my son. I did it with my homegirl Mecca from and for my homeboy [Geechi Suede from Camp Lo], who came up. And I was in the crib, I just recorded the song, and I’m like, “I love this song.” I wrote the hook and the verse.

I said, “Let me take it to Dame’s crib.” Jay was there and I said, “Yo check out my s**t. I got a new song.” I played it for them. Jay looked at me and said, “You know I’ma take that song from you, right?” I said, “What?” Then he gave me a bag full of money and I gave him the song. It’s crazy ’cause he kept the hook, and the way I was flowing. He said, “Yo, I’ma take the hook and I’ma take your flow,” and obviously he made it way much better than me.

Let me tell you something: Jay Z is the reason why I stopped rapping — because he was so ill. I said, “Damn, if I wanted to be a rapper, I wanna be him.” And he was just so good I said, “F**k that. I’m just gonna do beats for him.”

“D’Evils” [Produced by DJ Premier]

DJ Premier: Jay Z actually called me and recited the whole rhyme on the phone and gave me the concept of what he wanted it to be. So he already knew it was called “D’Evils.” He told me what the song was about. He did the whole verse on the phone and he even told me which scratches to use. So everything was pretty much already mapped out. He said, “I just need the track to sound like that atmosphere. I just need it to sound like the darkness of the lyrics.”

“22 Two’s” [Produced by Ski]

Ski: That’s like my nightmare song because I never liked that beat. People seemed to like it so I said, “F**k it.” Jay used to spit that verse [a cappella] every time we did a performance. He used to always have the crowd going crazy. So he said, “I’ma just make a song out of it.” I played that beat and he’s like, “I’ma use that one.” And I’m like, “That one? That one? I got so many better ones.”

There’s a skit with Maria Davis’ Mad Wednesdays [showcases]… the lady talking at the beginning. That’s where that verse became very popular. He used to spit that verse at her event. That’s why she got on the song and did the whole [thing] like we was up in Mad Wednesdays. That’s how she usually brought it to the stage.

[The track’s outro is] what she did if you cursed or if you did anything crazy in her club. She had the mic and was gon’ scream you out or make you get out or embarrass you or whatever.

“Can I Live” [Produced by Irv Gotti]

Sean C: It just speaks to striving and working. He was flossing on the record, but he was dropping a lot of jewels in the record as well. I know it’s like a drug-dealer song, but it’s really about work ethic more than anything. And life. I haven’t listened to Reasonable Doubt in a long time, but when I used to listen to it, that would be the song that would always play in my car.

“Ain’t No Nigga” (feat. Foxy Brown) [Produced by Jaz-O]

DJ Premier: I’ve heard Jaz-O say that there were a couple producers that were there that couldn’t loop up the “Seven Minutes Of Funk” sample [fast enough] and that’s not true. I got the call to come there and cook that song up and I couldn’t make it down there that day.

I just didn’t get there in the timeframe that they wanted to, so I just didn’t like the fact that he kept saying in interviews that some other producers, who are really famous for what they do, couldn’t do it. And that’s bulls**t. I told him, “Stop lying man,” and he was still doing the same thing in interviews. I’m over it now. I’m too grown to be upset with people over that, but I just want that to be clear that that is an outright lie.

But that’s one of the most amazing records [Jay’s] ever done and to this very day the crowd goes crazy. And Foxy killed it. She made her debut and from there, next thing you know, she got a big record deal.

DJ Clark Kent: It [originally] wasn’t gonna be her. It was gonna be someone else. We brought her in and he heard it. “This my little cousin, listen.” “Oh s**t.”

“Friend or Foe” [Produced by DJ Premier]

DJ Premier: That one I was just thumbing around for a beat. They paid me for other tracks and I just started looking for sounds that just sounded funky and original. I’m always known for having the obscure samples, so that’s still my trademark. And if it’s one that’s familiar, I still play it in a fashion where it’s like, “Wow, he put the end at the front and he put the front at the end.” [Ed.’s note: On “Friend or Foe,” DJ Premier flips the beginning notes of Brother to Brother’s “Hey, What’s That You Say.”]

I’m known for twisting things a whole different direction than how everybody else does and that’s what made me get a name — besides my scratching style. So that too is how I got “Friend or Foe,” and I remember Jay heard those horns and he was like, “Lay that down.” This was before Pro Tools [where] we could just dump music in five seconds. This was straight to two-inch tape.

“Coming of Age” (feat. Memphis Bleek) [Produced by DJ Clark Kent]

DJ Clark Kent: To know what that [being a teenage recording for Jay Z ] was like, you have to know what it’s like figuring out that he was gonna be the guy on the song. Imagine sitting in front of me going, “Yo rhyme,” for, like, three to four hours. Like, you have to rhyme for us to see if you should be on the song. So [Memphis Bleek] had to just keep rhyming. But his useful energy is what gave him the spot on the song. He sounded like the guy that you were gonna hand money to and he’d be like, “I don’t give a f**k about that I just wanna be with y’all.” He sounded like that.

“Cashmere Thoughts” [Produced by DJ Clark Kent]

DJ Clark Kent: If you listen to the record, [Jay’s] talking like a pimp. The name Cashmere — that was Jay Z’s [alter ego]. So “Cashmere Thoughts” were the thoughts of Cashmere. That song got done. The other records weren’t getting done, so that song got on his album. That’s the reason why I’m talking on the song, ’cause we’re talking like two pimps.

“Bring It On” (feat. Big Jaz and Sauce Money) [Produced by DJ Premier]

DJ Premier: [“Bring It On”] was just another random day that just turned into Sauce Money and Jaz-O being there. Jaz-O was always around at that time anyways. That one wasn’t really planned, but it just came together and everyone was there.

Jaz-O I already knew had it poppin’ because, again, he already had two albums out [1989’s Word to the Jaz and 1990’s To Your Soul] and, at that time, we were label-mates already. Sauce Money I had never heard of, so it was dope to hear him set it off with his verse because that set the whole tone.

Ski: Jaz-O was, at the time, probably still is, an excellent rapper himself. You gotta think: Jaz-O was the one who brought Jay-Z up.

“Regrets” [Produced by DJ Peter Panic]

DJ Peter Panic: We used to go to the Tunnel a lot as a crew. That weekend, instead of going to the Tunnel, I decided I was going to stay home and master my craft — I used to always make beats at Clark’s house.

I did the track and Jay came over the next morning to see Clark. I just played the track for him and said, “Yo, this is some new stuff I did last night. It sounds crazy. I just love the bass.” Meshell Ndegeocello was just emerging with “Dreadlocks” at that time, and because she’s a bass player, I was like, “Yo this beat is dope. I could even see Ndegocello playing the bass for this.” I wasn’t even planning the beat for him. This was just something I created.

Jay left and didn’t say nothing. The next morning, Clark’s like, “Yo, Jay wants to use that track.”

If you listen to the Reasonable Doubt album all the way through, 95 percent of those records don’t have any ad-libs on them because Jay is so self-assured in his records that he’d knock it out, one take. He did his vocal on my track and I was like, “Um, it was really, really, really dope.” But the track is an emotional track so you can’t just rock on it. You gotta get into the groove a little bit more.

I go back and I’m like, “Yo, I need you to do that again, but this way.” The room stopped and everybody’s looking like, “Is he really gonna do that?” Jay, knowing that I’m still up-and-coming, said, “Let’s do it.” He did his vocal, his ad-libs, and it was done.

Epilogue

DJ Peter Panic: Jay never really wanted to put out a lot of records; he just wanted to show that he was the best. If you hear him in most of his early records, he always says he just wanted to do one album and get out of the game. I think that they realized after you sign a contract with Def Jam, you’re now a business and they’re depending on you to keep on making music. That just kept him in the game.

Ski: It was honest music. It wasn’t fabricated. It wasn’t trying to do anything that was out of character. He kept it in character. He told his real life story and he did it in such a way, lyrically, it was poetic.

DJ Premier: I think he put this in a certain order of his top five Jay Z albums, and Reasonable Doubt is either number one or two. You heard the stories about how once he sold Roc-a-Fella he had his differences with Dash, but he was like, “I want my first [album’s masters] back.” Because that’s like your first child and that’s how it feels. You’re very, very attached to it, which doesn’t take away from all your other albums, because Jay has such an incredible catalog. But Reasonable Doubt is just that much of a great album.

DJ Clark Kent: What happened with him, I just challenge someone to show me that s**t happening again. Show me who’s gonna be better than that? And the reason why I say that is, let’s say you find somebody who actually comes up with better rhymes. Do you say ’em better? Do you got that flow? Do you got the ability to stop on a dime and then triple? Do you have that ability? No. This guy is the perfect package.