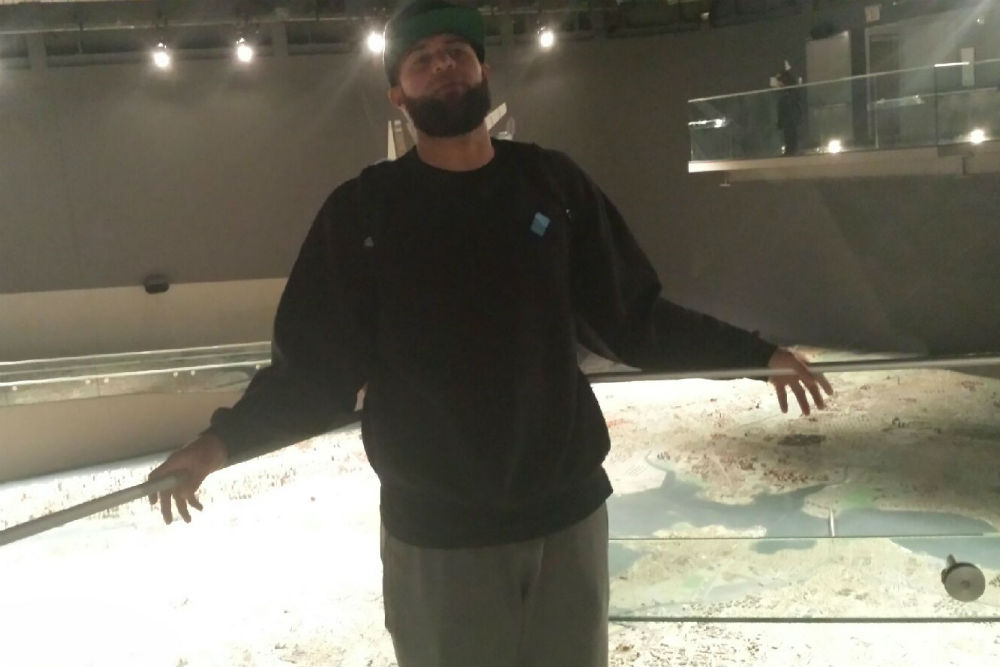

On a Thursday afternoon in April, Homeboy Sandman and I are circling the city of New York. We’re at the Queens Museum in Flushing Meadows Corona Park, a few minutes down the road from CitiField, where Sandman’s hometown Mets play. The park is probably best-identified by the outdoor presence of the famous Unisphere, the 120-foot stainless-steel globe built for New York’s World’s Fair in the mid-’60s, but the rapper prefers the indoor Panorama: a 1/1,200th-scale model of the Big Apple, built for the museum in 1985. He tells me he used to take girls here as an underfunded teenager growing up in Queens: “Yo, I can show you the whole world, and the whole city in one day!” was his endearingly corny pitch.

Standing 6’5” in a black sweatshirt, gray sweatpants, 33 ? cap — and, yes, a backpack — the 35-year-old Angel Del Villar II is a towering but never imposing figure. He carries himself with the veteran ease of an MC who’s been established in the game for as long as he has: a steady ten years of releases since the 2007 debut of his first EP, Nourishment, with critical acclaim and a devoted fanbase building gradually (if undramatically) up to his sixth LP, Kindness for Weakness, out this week. His confidence is a self-assured one, missing any kind of brashness; where Jerry Seinfeld once equated wearing sweats in public to announcing “I give up!” to the world, Sandman would likely tack on a shrugging “…giving a f**k what you think.”

Sandman might not know the whole globe just yet, but he’s got Gotham pretty well down. “I’ve lived in all [five boroughs] except for Staten Island,” he explains. “I lived uptown in Washington Heights, my first girl was on Academy. I lived in the Lower East Side, on 10th street, Alphabet City between B and C. I lived all over Queens: Corona, Elmhurst, Jamaica, Sunnyside. Now I live in Sunset Park.” Sandman’s NYC wanderlust is more a product of utility than romanticism. His primary funds are in straight cash, so it’s easier for him to shuttle between sublets than put down roots anywhere. (“I don’t have a lot of things, so it’s cool to just hop into a new place… Pretty much all I got is merch.”) Nevertheless, things seem to work out for the boy Sand — he lived on and off in the pricy L.E.S. for five years paying just $800 a month rent, and currently lays his head in a “stupid nice” Sunset Park apartment. “God just hooks me up with these amazing things,” he raves.

Despite not living in Queens anymore, he’s still rooted to his home borough through his family, who remains entrenched in their Elmhurst neighborhood. “My father ran for city councilman [in 2001],” Del Villar explains of his pops Angelo, a former bouncer turned attorney. “And he lost, he came in third place. But he got 20 percent of the vote. The winner was this guy named Monserrate. He got 27 percent, he was the incumbent. And then the second-place guy got 22 percent. But all those guys had big money, ads on TV, all of that, posters everywhere. My father got 20 percent just off of people saying, ‘Yo, Angelo’s running for city council.’”

It’s not particularly hard to draw the link between father and son in this respect. Like his dad, Angel has never had a ton in the way of big-money support or promotional push — his most prominent appearance on TV was in 2010 as an MC mentor on the MTV reality show Made — but through grassroots support, good word-of-mouth, and personal hustle, he’s carved out a niche for himself as one of New York’s best and most consistent underground rappers. It’s a small piece of the pie — he’s never charted an album on the Billboard 200, or even on the top 200 of the crit-polling Pazz & Jop list — but it’s big enough to keep him liquid, and on the good side of his succession of landlords in the Greatest City in the World.

Most of them, anyway. “I got evicted from [one place in Jamaica, Queens], still owe them a little bit of cash,” he recollects. “I’ll pay them one day when I’m in the surplus, you know what I’m saying?”

If there’s a rapper this century worthy of inheriting hip-hop’s “Teacha” honorific from KRS-One, it’s Homeboy Sandman — not least of all because that was literally his profession for two years in his mid-20s. He taught math and science at “a District 75 school, the citywide special-education district,” though he often ended up going off-book. “It was special ed, nobody gave a f**k,” he explains, referring to his unconventional lesson-planning. “I shut down math class and taught Roots when I was reading Roots… I would teach these kids about rhymes. I wasn’t even really rhyming at that time.”

The classroom mentality has translated to Sandman’s career as a full-time rapper, which started shortly after his teaching days came to a close. With humor, pathos, and relatability, he’s sought to inform and engage with his audience on matters of national relativism (“America the Beautiful”), charitable donations (“Canned Goods”), and fame (“Lonely People”), among countless other 101s.

But what has increasingly defined Sandman over the course of his career (and separated him from other hip-hop PhDs, including KRS himself) is the lack of rigidity in his rhymes. That flexibility can be seen both in the unusually relaxed pacing of his meter — Sandman’s lines only have as many syllables as they need, and he’s fine giving you the rest of the measure to catch your breath if need be — and the even rarer empathy of his preaching. This quality is even more evident in discussion with Sandman, where he constantly qualifies his statements by validating the points of the opposing perspective. (Talking about how he fits into contemporary hip-hop as someone in his mid-30s, he allows: “Maybe there are cats that are like, ‘Homeboy Sandman, this cat is 35 years old, that’s too old.’ Maybe they are. That’s cool, they’re free to do that.”)

Which isn’t to say that Sandman never finds himself caught up in the moment. In fact, one of the obvious highlights of Kindness for Weakness finds him in several such moments: the uproarious, Edan-produced “Talking (Bleep),” in which an incensed Del Villar offers six verses to six separate irritants, including MCs inquiring about guest features without mention of compensation (“They are the definition of buggin’”), fans who want the same song over and over (“I don’t make the same jam or record twice / I am way too nice”), and girls that automatically assume monogamy in their relationship (“She told me, ‘Grow up, stop acting like a kid’ / I had to tell her, ‘Yo, that ain’t what love is.’”) Each story ends with a wah-wah’d guitar (à la Charlie Brown’s teacher) providing an approximation of how ridiculous the offenders sound to the boy Sand (“You sound like thiiiiiiiis….”).

The most vitriolic section is saved for the Huffington Post — for whom the MC has actually written a number of editorials, but who insulted him by passing on one article of his “about the link between mass media and private prisons” and still reaching out to him to comment on “some rap beef / between a dude that’s mediocre and a dude that’s okay.” (He won’t say who the two rappers were, or ID the rapper in the final verse who “sucks that is way more famous than I am.”) In retrospect, Sandman has mixed feelings about calling out the publication. “I think I was kind of immature,” he says. “When it comes to music, I can’t censor myself, particularly if some s**t is hot. So I have to be like, ‘That s**t is wild.’ But, you know, I wrote a piece that HuffPost decided they didn’t want to rock with. That’s their right to do that, I’m happy they gave me that platform.”

The best-publicized instance of Sandman getting swept up in the emotions of a moment, however, came in an op-ed for a different publication. During the 2014 NBA playoffs, when Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling came under fire for making racist statements recorded on tape by Sterling’s then-girlfriend, Sandman wrote the provocatively titled “Black People Are Cowards,” in which he excoriated the Clippers team for not making more of a stand against their boss than turning their shirts inside-out during warmups. “I have come to the decision that I agree wholeheartedly with the owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, and I too do not want black people invited to my events,” wrote a sardonic Del Villar. “What do you call people that pretend that these ridiculous gestures actually hold some weight rather than face the fact that we are the laughing stock of the entire planet?… I call us cowards.”

The piece was understandably polarizing, and attracted 1.5 million views — one million more than any of Sandman’s videos have on YouTube. But despite some Internet outcry, Sandman found himself underwhelmed with the public reaction to his article. “I was out every single night after writing that article,” he remembers. “I was like, ‘Yo, I know the cats are gonna have something to say, one way or another, and I wanna be present, and I want to be front and center.’” But the confrontation never came: “Nobody says s**t, nobody did s**t, nobody had nothing to say, nobody had nothing to do, nobody wanted fellowship about this or that. And I was kind of like, ‘Yo, you kind of alone on this… Maybe you should stop and think about why.’”

Today, he says he wouldn’t write the article: Not because he disagrees with what he wrote, but because he questions his motivations for writing it in the first place. “From early in my life, I’ve always had these chances that other people in my life didn’t really get,” he explains, referring to a background that includes private high schooling in New Hampshire and an Ivy League undergrad education at UPenn. “And I’ve been like, ‘Yo, I’ve gotta make sure cats know I’m still down for the cause…’ I started [wondering], ‘Why is this so important to you, to make sure that you’re at the ready if it ain’t important to everybody else? Especially when you’re the one who doesn’t even have to deal with a lot of this s**t?’”

Sandman says he tried to keep his preaching to a minimum after that, even when his buds in the teaching community would try to get him to come talk to their kids. “There did come a time I was like, ‘I’m doing this for me…’ Like, I’m lying to myself, telling myself this is productive for the world. I’m doing this so that I feel good. And I really laid off it and didn’t do it at all.” Lately, though, he’s started dipping his toes back in, visiting a handful of schools. “But always just to talk about me, my life,” he clarifies. “Even when I’m talking with kids now, I’m different. I’m like, ‘I’m not here to tell you the truth or nothing. Because I’ve got my truth and you got yours.’”

Earlier at the Panorama, Sandman had been ruminating on his longtime love for the exhibit, and his incredulity at it being overlooked for its showier counterpoint: “The Unisphere is pretty clichéd as far as Queens [landmarks],” he rhapsodized. “But nobody knows about this [Panorama], and it’s right next to it!” An hour later, as we walk out of the Museum to get a closer look at the tour-book favorite, the analogy finally strikes Sandman. “I was even thinking it’s kind of symbolic, being out here. Just for the fact that it is some s**t that you never even knew about, that’s really def. Right next to the clichéd s**t everybody knows about.”

Chances are, Homeboy Sandman will live a long, happy life as a cult figure on underground hip-hop sanctuary label Stones Throw, without ever threatening a true mainstream breakthrough. Kindness for Weakness might be his best album to date, and is certainly one of the best hip-hop albums of the year, but Sandman isn’t the kind of rapper whose albums inspire passionate debates, and he’s not the kind whose sixth LP will convert you if the fifth one didn’t. There’s no jaw-dropping special-guest choices, no big-name producers or flirtations with exciting new subgenres, no career turns to project an easy narrative onto. It’s just a series of engaging, creative, and uniquely personable rhymes over an array of jazzy, clever, mildly unpredictable hip-hop beats. It could have been made in 2006, or 1996. But it’ll still sound great in 2026 or 2036, too.

A lot of rappers of Del Villar’s temperament would use being cordoned off into a relatively limited subset of ‘head-dom as incitement to rain fire and brimstone on hip-hop’s mainstream at any given opportunity. But Sandman is too old for that s**t. He doesn’t pay as much attention to the Futures and Young Thugs of the world as the rest of the Rap Internet, but he’s got nothing against them, either, and he says he was surprised to find out that the poster boy for Millennial MC’ing actually has bars. “All these cats I know that are like, ‘Yo, we represent real hip-hop’ were like, ‘Yo, f**k Drake,’” he says. “So I figured I would hear some Drake and be like, ‘That s**t is cold wack.’ And then I was like, ‘This cat is actually nicer than a lot of cats.’”

Ultimately, he’s learned to be thankful for the audience he has. “I spent a lot of time being mad, like, ‘Yo, our s**t is hot, why don’t you put our s**t on? Why don’t you put my s**t on?’” he says. “But I’m happy that cats get to hear this, and I’m optimistic too. I feel like, this is my ninth year rhyming, you know, and I feel like every year… I see in my life every year, the exposure grows.” He also feels like he’s getting better, not just at spitting, but at being himself. He shares a quote that appears in Miles Ahead, the Miles Davis quasi-biopic currently in theaters: “He says, ‘It takes a long time to sound like yourself…’ I feel like with everything I do, I’m getting further away [from my influences], and coming more into my own.”

https://youtube.com/watch?v=7I1U1Zhi70Q

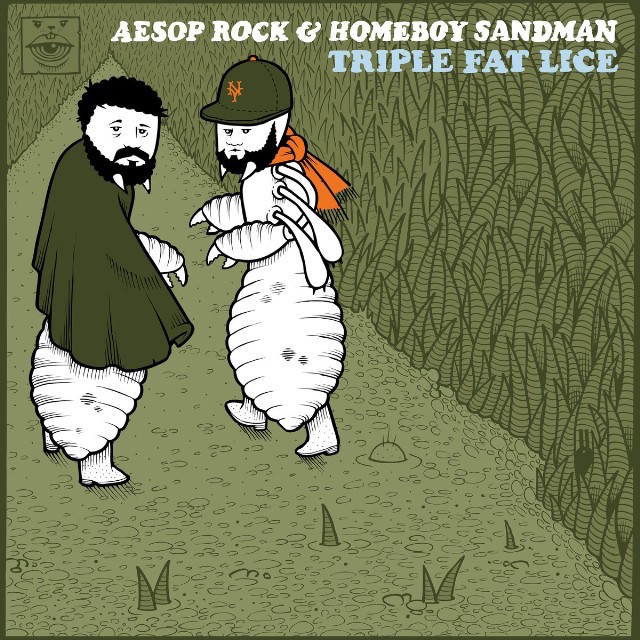

The best song on Kindness for Weakness (or at least the most definitive) is the closer, “Speak Truth.” Over bleating, sympathetic horns, Sand testifies about the importance of performing the title action — “Speak truth as your favorite pastime / Speak truth, even when it’s different from last time” — before he’s joined by a Greek chorus (including Aesop Rock, the kindred-spirit MC with whom Sandman recently released the collaborative Lice EP) plaintively warbling, “Truuu-uuu-uuuuth…” It’s a risky song, one that could sound facile without the appropriate gravity, or leaden without the necessary levity. But in Sand’s hands, it feels as profound a sentiment as you’ll hear in 2016 hip-hop, and the sort of manifesto that his career has been quietly building toward for a decade.

“I definitely try to do that,” he claims, of following the song’s central tenet. Then, he amends: “I guess, ‘Speak truth, or don’t speak at all…’ Because I don’t always need to say some s**t. At some point I was like, ‘Yo, speak truth always, and you need to go out of your way to yell and scream.’ I don’t feel that way anymore. I feel like, pick whatever spots I feel like picking, and then speak truth there… Some of the things I’m talking to you about, like discovering insecurities, discovering overcompensation, these are not always things I saw in myself. Now that I’m able to see them more, I’m able to speak more truth about them, or live more truthfully regarding them. So, you know, as I continue to learn more about myself, it’ll help with the truth.”

And for all he’s learned, Del Villar offers this: “I’m more comfortable saying now I’m the most privileged dude. Nobody ever had a better life than me. I never met nobody ever had a better life than me, from no walks of life, no version, no color, age… It is a good thing to be able to say.”