It’s The Garden of Earthly Delights in downtown Manhattan: home to halfway forms, magical creatures, and outlandish “cut-ups.” Two wolf heads are rendered in taxidermy; their tongues, daggers. One hangs upside down from an invisible thread opposite the other in a suspended kiss. Stiletto heels have horn transplants, two illuminated coffins bracket each side of the room, and an odd-looking cross, rendered in neon, hangs above it all – not Christian, not Satanic, but something else. This is the top floor of the Rubin Museum. This is an art show, and it’s called Try To Altar Everything.

The artist is musician/occultist/professional provocateur Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, and the method — the “cut-up” — is a style of Dada collage. Popularized by Beat generation artists Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs, “cutting up” involves rearranging pieces of texts into a new whole: literally dissecting with scissors and stitching back together. To “cut-up” is to throw out those old notions of traditional congruity and edit – alter – everything.

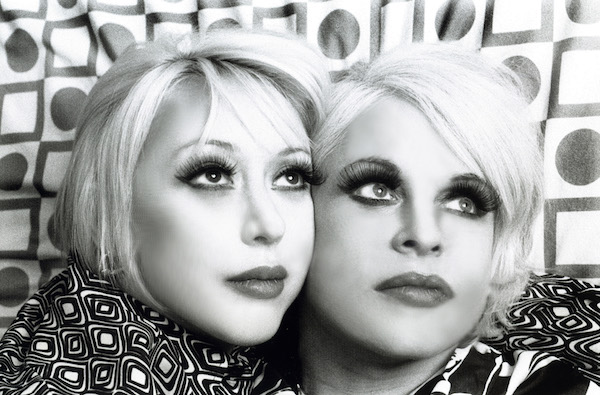

Enter Breyer P-Orridge, a cut-up h/erself: a “pandrogyne,” a third being neither man nor woman. Beginning in the early 2000s, s/he took on new gender pronouns and began undergoing elective surgeries (breast implants, liposuction, tattoos, hormone therapy, etc.) alongside h/er spouse, the dominatrix and registered nurse, Lady Jaye, to look more like the other. Like Aristophanes in Plato’s Symposium, the pair believed that they were two halves of the same being, stuck apart. “Some people feel they are a man, trapped in a woman’s body. Some people feel they are a woman trapped in a man’s body”, they explain: “Breyer P-Orridge just feel trapped in a body.” Genesis was naturally devastated, then, when Lady Jaye succumbed to cancer in 2007, but maintains h/er devout belief in the system that they created together. Referring to h/erself in the first-person as “we,” Genesis asserts that s/he represents the couple on Earth, while Lady Jaye does the same in the afterlife: “s/he is her/e.”

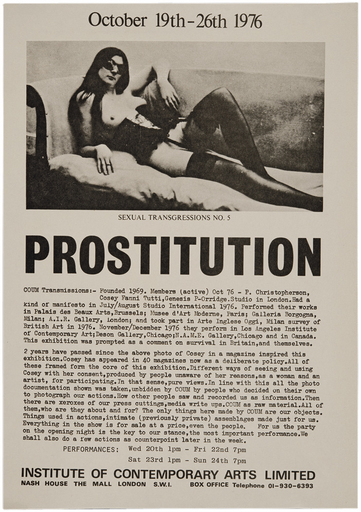

This is only one branch of Breyer P-Orridge’s life-turned-art. S/he has been cutting up for a long time now, having first gained notoriety for staging transgressive exhibitions in the ’70s alongside h/er performance collective, COUM Transmissions. Highlights include: blood enemas, masturbation rituals, and more. So notorious did the group become that they were even debated in Parliament. Nevertheless, little did those MPs know what was in store: Throbbing Gristle, diviners of industrial music, and later, Psychic TV, a self-styled “propaganda device” for a new, magickal religious sect, Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth (TOPY). Think of Thee (now defunct) Temple as the codification of Breyer P-Orridge’s philosophy, and know that its Bible is over 500 pages long, and membership involved mailing in pubic hair and semen samples.

Similar offerings can be found at the Rubin, sans bodily fluids (the institution’s restriction, not the artist’s), as part of a new site-specific work. Visitors are invited to bring small, symbolically meaningful objects to the museum as donations for display. Already there are photos of couples kissing, keys, USB drives, and other assorted personal items. Breyer P-Orridge arranges them in small jars that dot the walls of the museum, and in doing so, has altered the space into one of intensely devotional energy: conceivably the realest altar Thee Temple has ever seen. Its membership, too, has continued to grow: the first thousand participants were awarded special Psychick cross pendants made in Tibet.

Perhaps this is testament to the staying power of Breyer P-Orridge’s ideas, which some have derided as either too extreme or just short of insane. Genesis would be the first, however, to remind her detractors that — as her forerunner Allen Ginsberg once wrote — sanity is just a “trick of agreement.”

SPIN chatted with the lifelong firebrand to see what’s kept h/er going these past four decades. Read our conversation below, and check out Try To Altar Everything at the Rubin Museum, open until August 1.

Much of your work concerns spirituality and devotion, including the creation of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth. You even had Psychick crosses made for the first thousand people who donated offerings to the Rubin.

That’s our ongoing logo. We designed it intuitively: it contains the Christian cross, and it also contains the cross upside-down, so it negates a position. It’s not one or the other: the line through the center is saying, “somewhere in the middle,” that’s the place that we should be. But that’s the minority, so it’s smaller. The vertical is time, moving. The more we looked at it, the more we thought “this is a beautiful symbol! It can be interpreted so many ways, but they’re all positive.”

Rather than just get them made in China, we were fortunate that the Rubin Museum and [curator] Beth Citron, went with me to Kathmandu. While we were there, she located Tibetan refugees, who then made all the crosses for us. We invited them into the process of the exhibition: they got money that they would not have otherwise gotten. We were actually giving back to the inspiration of a lot of what we do.

There’s [another work] that’s also interactive. There’s a beautiful, red armchair that Lady Jaye had in her apartment when we met, where we used to sit and cuddle, fall asleep together, watch TV together, and make love, actually! That’s going to be there on a print, and certain days, we’ll be in the museum. There’s a telephone: People can call in and ask me about the exhibition. [We can] actually share our thoughts: not just present them, but actually be present and answer for them.

There’re also 20 or 30 other works?

Yeah. [Those works are all] focused on their spiritual, devotional content… or intent.

The pieces are always things from my daily life, seen in a symbolic, devotional way. That’s what brought me to Nepal, and why we fell in love with Nepal. You can be walking along, going to work in an office, and just to the side, someone is burning a relative and sweeping the ashes into the holy river. Somewhere else there’s a sacrifice, and somewhere else there’s chanting for healing. It’s all integrated. Nothing is separated: death, life, the processes of life, the processes of devotion, loving, and worship, are all integrated in what we feel is a healthy way.

Where did your interest in ‘magick’ and spirituality begin?

It really took off when we were ten years old, in 1960. Two things happened. My father gave me a copy of Seven Years in Tibet, and that’s what turned me on to Tibet, and Tibetan Buddhism. Right there. We read this book and were enthralled. “How nice to have a culture that’s about unconditional love, generosity, kindness, healing, pacifism.” All the things that seemed to me to be the best qualities of the human species were the ones that were amplified, instead of bigotry, punishment, and intimidation: all the things that are so sadly part of monotheistic religions, where life is a game that you win by not getting punished in the end.

So it was that, and then my grandmother on New Year’s Eve. For some reason the adults on New Years Eve decided to have a séance. They got a wine glass and put it on the table, and had the alphabet in a circle, written on bits of paper, and a “yes” and a “no.” People would put their finger on [the glass] and it would start moving. They would ask it, “is anyone there?” And it would go “yes.” They would ask a question, and it would spell out the answer.

It was all very hilarious, and not very serious, but [the glass] was moving. And nobody was sure why it was moving. Then my grandmother said “let me sit there.” So she sat down, and put her finger on it. As soon as she put her finger on it and said “is anyone there?” it started to move so fast. No one else could keep their finger on it. It kept spelling out words, really, really, really fast. Then she took her finger off, and it spelled about two and a half more words, flew off the table, and smashed.

Wow.

Exactly. We said to her the next day, “What was that?” She went, “Oh, I used to be a medium, but I stopped it because it was too frightening.” Then she said something really odd: “Don’t ever grow a beard. It will destroy your powers.” We were ten, nearly 11, thinking “What the hell does that mean?” It was a bit scary, we were like “Oh, why did she say that?” Yet it was so powerful a moment that when we turned 18 and went to university, the first thing we did was grow a beard. To say, like, “Well f**k you, Granny [Laughs.], I’m going to grow a beard, then!”

Did you feel a loss of powers?

No. Not at all. [Laughs.] No we didn’t, whatever that means. But after about a year we got rid of it, and never grew it again. But it was that strong a moment that made me want to rebel against it, even all those years later.

Do the crosses still represent TOPY?

They represent a way of life, and a desire for a truly devotional experience of living. The Psychick cross becomes a clue that you may be with friends. That, in and of itself, was the original intent: a non-verbal clue, somewhere on your person, whether it’s a huge tattoo or a little tiny cross. Something that people will [see and] go “We probably have a lot in common.” What a wonderful way to begin a conversation, and feel that you have support systems.

Our ultimate aim is to set up an actual community. Literally, a village. A village that becomes a think tank that experiments with different dwellings, different ways of being, different ways of surviving, different ways of sustaining, and as an example, in and of itself, gives hope to others, because we are in a crisis situation. There’s no question. It doesn’t matter how many band-aids those in control want to throw around. The odds are very high that there will be a Mad Max world in the next 20 years.

The crisis, is that climate change? War?

Oh, a collapse! A total collapse of the current system. The alternative is totalitarian capitalism. The problem with that is that it will have to sacrifice huge numbers of people to famine, drought, disease, and it will do that, at least in the very beginning, in a racist way. Africa’s basically ignored in foreign policy because it’s black. Let’s get real here. They don’t care because they don’t care what happens to blacks! That’s the worst part of what’s been happening in politics: it’s giving credence to racism.

We’ve been making a documentary under the auspices of Hazel Hill McCarthy III, it’s called Bight of the Twin. It’s a great reminder for me that, in Nepal, the average YEARLY wage is $140. A year. In Benin, in West Africa, it’s less! You have to keep on and on reminding yourself — never mind everyone else — that 90-plus percent of human beings wake up and their only concern is “will I eat today?” “Will my children eat today?” The answer, for many, is “no.” That’s a travesty, and we’re all guilty of them not being able to say “yes.” All of us, me included. We’re all guilty because we live privileged lives.

Does your exhibition at the Rubin Museum confront that issue?

To a degree. Not enough, but its initial premise was not overtly political. That’s why there’s a telephone: because it’s a conversation that needs to go deeper. If you can generate questions, and make yourself available for those questions – at least more so than the average artist does – then there’s something.

We have had people talk to us already that have developed really simple, sustainable dwellings, that could be used for all those displaced refugees: cheap, collapsible, and reusable. So why aren’t they being manufactured en masse? William Burroughs is so brilliant: he said to me once, “When you want to know why something is not happening, Gen, look for the vested interest.” Why is there no cure for cancer? Because the medical industry doesn’t want one! And the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want one! Because they would lose too much money! Why is there no car that runs on water? Because the petroleum industry doesn’t want one! Why were there no infinite light bulbs? Because they didn’t want one! Our world has become reliant on disposable, incurable consumption.

You mentioned earlier how your spirituality differs from monotheistic religion, in that you focus on being a better person in the here-and-now.

Absolutely. It makes you an enemy of bigotry, of racism, preconceived bias, hatred, and intimidation. Once you’re looking for wisdom, you have to look at why things happen and why people behave how they do: you cannot, in all conscience, accept any form of prejudice. It makes no sense. It’s anathema for anybody who’s looking for wisdom.

How do you square that, though, with COUM and Throbbing Gristle’s confrontational tactics? Bodily mutilation, for one?

Different ages require different strategies. Things don’t happen in a vacuum, and artists don’t make work in a vacuum. COUM Transmissions began almost as Theater of the Absurd, and eventually became focused in on transgressive behavior and taboos. Why do societies have rules and regulations about certain behaviors, usually sexual? You only have to look at different societies to realize that they’re arbitrary! What’s illegal in one country is the norm in another! In one country you can have X number of wives, in another you can only have one. In another you can have two husbands, and in one country you can have anal sex, and in another one you can’t! You have to go, “well, if it’s just different everywhere, that means it’s arbitrary.” It’s imposed from above by the people with the power.

That doesn’t mean it’s a natural choice, because it would be the same everywhere if it were. So who’s making the decisions about what’s acceptable, who’s deciding what is transgression, and what are their motives, as it’s a choice? That’s when it gets political, and that’s when you get in trouble with the establishment. You’re suddenly going, “just because you don’t like this, doesn’t mean it’s inappropriate. It just means you don’t like this! What if you decide you like it in 20 years?”

For example, in 1976 in October we had an exhibition at the ICA called “Prostitution.” Amongst it were four little tiny sculptures that we made, myself, using used tampons as one of the elements. To just show you how silly it was: they were a throwaway, last minute thing. One was an art deco clock, filled with one month used tampons, and its title was It’s That Time of the Month. There were questions in Parliament! We were called “wreckers of civilization” by an MP, for those little sculptures! Now, really? Really? Isn’t that obviously a joke? Then, six years ago, Tate buys those same four tampon sculptures, for their national collection of British fine art. Now they’re in the collection with the Turners, and the Constables. So what’s real, and what are rules, and how come they move so often?

Are you happy to see them in a museum? Does their purchase mean that they’ve lost their edge, or that you’ve changed society for the better?

Well, let’s hope for the latter. We changed British society for the better, but without naming names, we’ve had struggles to have new used tampon sculptures shown in other places: in other countries. From 1976 to now, what’s that, 40 years? So in 40 years, Britain’s become able to accept the existence of used tampons. [Laughs.] Maybe in other countries it’ll take another 40 years.

But yes, we feel vindicated. It’s not anything more than that. We feel vindicated that we spoke about something that we thought should be said, and sometimes the best discussions are those things that people find uncomfortable. They found it uncomfortable to the point where they thought we would destroy the British empire, and now they can live with it. Therefore, something has happened that’s positive. Now we need to export that tolerance to other places!