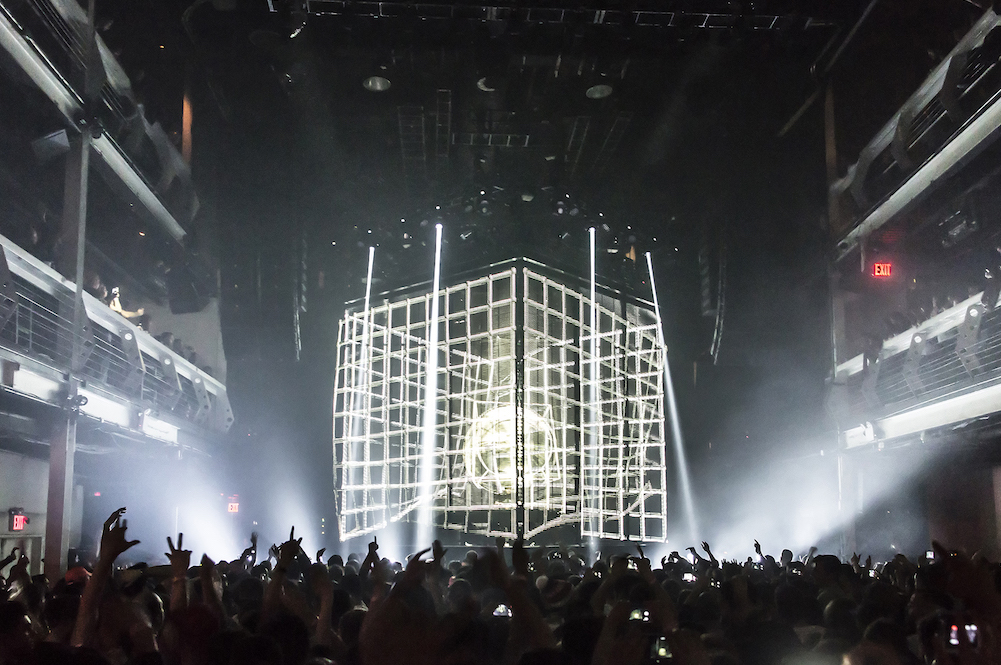

Eric Prydz is barely visible inside the largest hologram in North America. The enormous, luminescent box projects 3D images — undulating geometric landscapes, glowing meteorites, crackling thunderstorms — to 3,000 whooping fans at Manhattan’s Terminal 5. In the sound- and light-booth three stories up, a different kind of chaos is unfolding: The visuals engineer moves miniature versions of those icons (which took a year and a half to make) around a computer screen like he’s playing an especially stressful game of Tetris, executing the biggest series of shows (at least from a ticket sales perspective) that Prydz has ever played.

“Nothing’s pre-programmed,” Prydz tells me a few days earlier at a midtown coffeeshop. “Every show is unique. Doing it that way, there’s a lot of problems that can happen. It’s not pressing play.”

This commitment to craft sets the 39-year-old father of two apart from his peers who do press play. Bridging critical legitimacy and commercial viability as few DJs of his caliber have been able to do successfully, he’s no longer the guy who did 2004’s “Call on Me” — which topped charts, blasted singles sales records, and paved the way for post-Eurodance copycats. More than a decade away from that song’s Steve Winwood tribute, these days Prydz is more closely associated with the hipper set: CHVRCHES, whose “Tether” he sent further heavenward last year, and Four Tet, who remixed “Opus,” the gargantuan lead single from Prydz’s 19-track debut LP of the same name. He stays consistently relevant with a simple idea for what his music should sound like. “It’s always about being at a club,” Prydz says. “On the dance floor, at a festival, in a dark club somewhere — that’s what the music is made for.”

Also Read

The 101 Best Albums of the 2010s

Growing up in Stockholm, Prydz fulfilled a certain Swedish stereotype. “Eric Prydz as a 6-year-old: huge ABBA fan,” he says. His dad “could barely stomp his foot to a beat,” but his mother would go out dancing at local clubs and bring the party home in the form of vinyl LPs that she would then play for her young son. “There was always music on at the house,” he remembers. “American disco, German and Swedish stuff, a lot of Italo disco from Italy.” The song that made the biggest impression on him was ABBA’s jingling paean to lovesickness, 1980’s “Super Trouper.”

“There was something about it that just made me go, ‘I just want to listen to this over and over again,’” he says, smiling at the memory of his first musical love. “I loved when the chorus kicks in and it gets all electronic. It had live instruments, but then it had these synthesizers.”

In the early ’90s, his tastes took a much darker turn. Prydz started listening to the jagged pulse of electronic body music (the bastard child of post-industrial and electropunk), led by innovators like U.K. outfit Nitzer Ebb, Belgium’s Front 242, and the Canadians in Front Line Assembly. As Prydz would continue to do throughout his life, the burgeoning beatmaker had his fingers in a few different outlets while in school. He toyed around with an Amiga 500, a very early desktop computer model from 1987 that was discontinued in 1991. “It had a music program where you could only do four sounds at once,” he says. “It was very limited.” Following a perfunctory audition for a classmate’s band, EBM aspirants Enemy Alliance, Prydz learned slightly more complex musical expression by playing electropads, a combination of drums and synthpads. “They made dark synth music,” he recalls. “It was right up my alley.”

A few years later, in 1996 or ‘97 by his recollection, Prydz took a break both from his band and his personal music-making to fulfill another archetype — that of a disgruntled young slacker, working a boring desk job while skateboarding on the side. Except, he says, “Instead of using the vacation pay for rent and stuff like that, I bought this brand-new workstation synthesizer that just came out, the Roland MC-505 groovebox [a hybrid of a MIDI controller, music sequencer, and drum machine]… I got obsessed with it. I didn’t hang out with my friends anymore, I was just sitting at this box, day and night, making music.” A friend who ran a skateboarding shop happened to be playing a cassette of one of Prydz’s tracks when an A&R scout from EMI/Parlophone also happened to be in the store; in 1999, Prydz signed his first record contract and moved to London. “That’s how it started,” he says.

That’s how — or rather, when — Opus started as well. Prydz had been thinking about his debut album since he first inked his major-label deal, but due to the fine print he couldn’t even start planning it exactly as he wanted until recent years. “There’s always been input from everyone else,” he says. “They wanna say, ‘We want the record sleeves to look like this,’ or, ‘That track is nice, but can you change it a little bit more there?’” Even before he was freed from his contracts, Prydz had already started seeking artistic liberation with alternate identities and aliases that he still assumes to this day: Pryda, his progressive-house persona and the name of his label, and the harder-driving Cirez D, associated with his techno label, Mouseville. “The record company owns your real name, so I could only release Eric Prydz music through them,” he says. “They only wanted music they could sell, and I wanted total freedom to do whatever the f**k I want to do.”

In 2012, he did just that, unveiling 37 tracks on the exhaustive Eric Prydz Presents Pryda; last year, to celebrate the tenth anniversary of his label, Prydz released three EPs as Pryda. Opus, released in February through Virgin, is both a continuation and extension of this excavation — a mix of demos that, for years, have been sitting in the vault (which he estimates to contain thousands of tracks) and more recent tracks that more accurately reflect his evolution as a producer. “If someone doesn’t know who [I am] and what I’ve done over the past 15 years, this album would be like my business card,” he says.

Opus’ surging arpeggios and Human League-esque bombast are not only a long way from “Call on Me,” but also Prydz’s earliest days making music, when he had an allergic reaction to what he calls “cheese.” While still living in Stockholm and spending a lot of time with the DJs in Swedish House Mafia, Prydz suggested they tone down the emotional grandiosity of their signature big builds and even bigger bass. “It was a good thing that I left, because if I was still there and I had a say,” he told Beats 1 host Zane Lowe in a recent interview, “it would never have become as successful as it did.” He’s come a long way — Opus shines with the brightness of a million moist eyes — but he mitigates corniness by avoiding EDM’s myopic focus on the drop. “You get goosebumps when it kicks in,” he explains. “I try and get that same reaction with melodies; the drums are there to show you the tempo. It’s the way I express myself musically.”

The other way he expresses himself is witnessed at his after party at Manhattan’s newest dance club, Flash Factory, where Prydz — as his dark-knight alter ego, Cirez D — unleashes brutal techno to a 525-capacity room packed with die-hards. His low-end stabs ripple through the room like a sonic boom as he bobs to the beat jovially behind the decks, occasionally leaving his post to refill a tumbler of Jack Daniels from the booze table behind him. Whether he’s riding leftover adrenaline from the exhilaration of performing earlier in the night or simply charged up to throw down some more, Prydz’s after-hours set reminds me of something he said in our interview a few days prior: “We always try to one-up the last show in a big way.” But tonight, as he cheekily slips in a sample of Snap!’s “The Power” between thundering beats, he’s one-upping his own ambition.