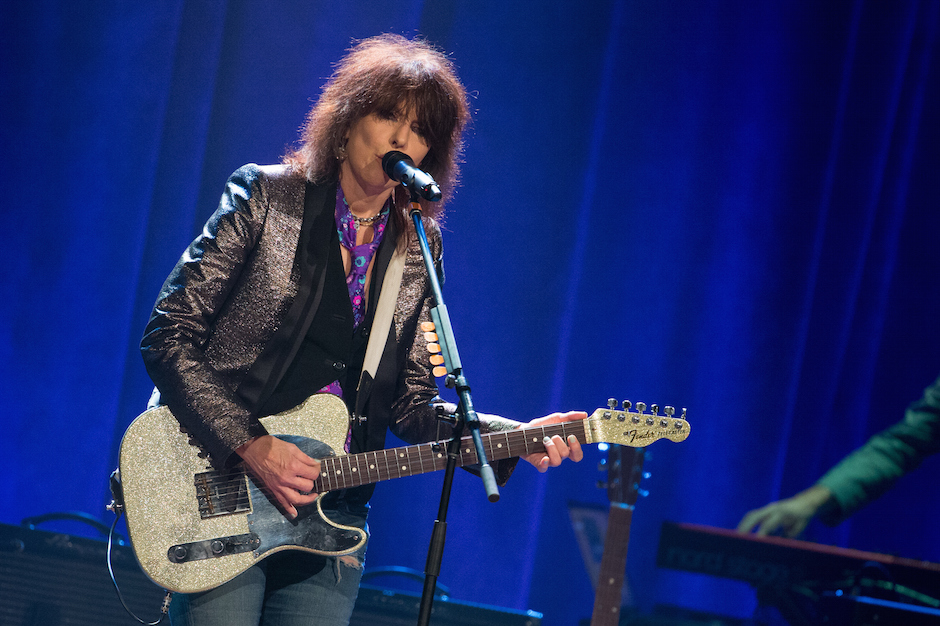

“You know, if you don’t want to entice a rapist, don’t wear high heels so you can’t run from him. If you’re wearing something that says ‘Come and f–k me’, you’d better be good on your feet…” Surprisingly, this statement isn’t the gaffe du jour of a Republican presidential candidate — it comes from Chrissie Hynde, the frontwoman for the Pretenders, who once penned the line, “I’ll never feel like a man in a man’s world.” For over 30 years, the singer has been the driving force behind the band, which has, in its multiple incarnations, sold more than 25 million records and garnered widespread respect, in part for her lyrics and persona evincing a kind of femininity that’s tough, wry, and regally detached while still bristling with a very human need.

In one of the band’s most famous songs, “Brass in Pocket,” Hynde’s voice shifts between a tease and a command in the same verse: “‘Cause I gonna make you see / There’s nobody else here / No one like me / I’m special, so special / I gotta have some of your attention / Give it to me.” The women artists who came after her considered her a rock’n’role model. Madonna famously recalled seeing Hynde perform in Central Park back in 1980. “She was amazing: the only woman I’d seen in performance where I thought, ‘Yeah, she’s got balls, she’s awesome!’,” Madge said. “It gave me courage, inspiration, to see a woman with that kind of confidence in a man’s world.”

Hynde’s position as one of the most powerful, influential women in rock makes her comments all the more devastating, a misplaced display of bravado from a woman who had an early hit covering “Stop Your Sobbing.” Her remarks come from an interview in The Sunday Times originally intended to promote her memoir Reckless, which includes, among the memories of her ascent as the black-jacketed goddess of Rock Olympus, the story of her rape at age 21. A member of a motorcycle gang promised to give the young Hynde a ride to a party and instead drove her to a vacant house, where he assaulted her. However, in her account within the memoir, and to her interviewer, there is none of the righteous rage to be expected from the victim of such a vicious crime: “This was all my doing and I take full responsibility,” Hynde says. “You can’t paint yourself into a corner and then say whose brush is this? You have to take responsibility… I mean, I was naïve.”

Hynde’s naïveté is far broader and more damning than she supposes, particularly in her unforgiving assessment of what other women should do to prevent their own rapes (spoiler alert: it’s that bitter old chestnut about hemlines and cleavage). Her words are like embers of a still-lit cigarette tossed casually in a trashcan, and they have ignited a blaze of rebuttal online, including a powerful essay by Lucy Hastings, director of the group Victim Support.

Also Read

30 Overlooked 1994 Albums Turning 30

I’m a survivor of domestic violence and sexual abuse myself, a child who was told that being hit with a belt was “discipline,” that I deserved to get slapped in the face for yawning during homework time and setting off one of my father’s “bad moods.” As a child, I was told by my own mother and a therapist I was forced to see in my teens, that the neighbor boy (a few years older and more than a few pounds heavier than I was) who stuck his hands down my skirt, stuck his fingers inside me, almost every day for two years, was “just exploring, like kids playing doctor.” As such, I should light my own torch with Hastings’ fury. And yet, I can’t stoke the coals. I feel only a cold sadness for Chrissie Hynde because I remember what it was like to be crushed by the stone-press of denial.

Hynde’s clipped, elliptical account of one of the worst moments of her life — “When you play with fire, you get burned” — resonates with me; or rather, with the woman I used to be, who froze out her terror and rage in an Arctic cynicism, who cloaked her wounds in a “so over it” attitude. I believed that I was the architect of my greatest suffering because that’s what my parents taught me, because that’s what they learned from a culture with a bedrock of “boys will be boys,” an entertainment industrial complex in which violated women are objects of intrigue (whether they’re on CSI or SVU, Game of Thrones or the Lifetime movie of the week), and a legal system that often doles out more jail time to drug dealers than rapists (assuming said rapists even see the inside of a courtroom). There is another, equally powerful force crackling through this current: a desire to be in control. Because if I was too rowdy, too loud, then I deserved to be hit, and if I deserved to be hit, there was some semblance of logic, of order, however brutal, to the world. To every action, an equal and opposite action.

For years, I wouldn’t use that scarlet A. What happened to me wasn’t abuse, it was discipline, “playing doctor.” As a teenager and young twenty-something, I listened to co-workers espousing the values of corporal punishment. I would nod along when they’d say that they’d taken an ass-whooping or two, and it made them smarter, stronger, and more resilient. I was even known to say, with a wry laugh, that I’d been hit, too, and look where I was. I had a scholarship, a job. I learned to ignore that sizzle at the back of my head, the sound of some desperate animal trying to claw under an electric fence. Reading the comment sections in thinkpieces about Hynde tells me that I am not alone in my digging. One commenter on Jezebel’s writeup talked about being raped in her own bedroom: “I woke up at 3 in morning with a knife at my throat. And I still blamed myself.”

Another commenter said that “even my most feminist of female friends who have been assaulted try to shoulder some of the blame.” A commenter who described responding to sexual assault calls at a hospital echoed this sentiment: “When I responded to hospital calls, they would spend a lot of time thinking and critiquing their own actions.”

These people, like Hynde, like me, can spend a lifetime divining a perfect alchemy of self-blame, a set of runes and codes where leaving the window cracked, or accepting that ride, or looking at our father “the wrong way,” or letting the neighbor boy take us out for ice cream, conjures the ache to end all aches. We do this because living under the glass jar of appropriate hemlines and moderate drinking (or better yet, total temperance), walking with our keys between our knuckles (and always in a well-lit area, never in a shortcut), getting alarm systems and buddy systems, feels safer than the alternative: an unfathomable wilderness where we can be badly hurt just because the wrong man happens to walk under our windows, or picks us up on his motorcycle, or lives one court over, or gives us his last name.

Believing that I brought my abuse on myself was like living with a shard of ice hovering inches from my heart, that one wrong move would stake me. But every time I leave the house, I risk that one wrong move. That one wrong move is called life. After several years and many panic attacks, and with the help of gifted therapists, I started to accept — slowly, painfully, and with many hiccups of “If only I’d …” — that only my abusers were to blame for my suffering. I lived in a cruel, violent world among cruel, violent people, and that yes, it could happen again.

For the sake of all survivors, it’s vital that we shout down the rape apologists, even if they’re people whose work we would otherwise admire and are victims themselves. Chrissie Hynde’s remarks are infuriating, but they’re also heartbreaking — a dispatch from that glass jar. Her efforts to justify her own assault speak to how deep the hooks of rape culture have sunk inside her, and how profoundly she’s been scarred. So, somewhere inside the furnace of our collective rage, there should be a soft gray spot of sympathy for her, since she could not manage to feel it for herself. Some days, knowing the truth that what happened to me was never my fault makes me feel smarter, stronger, more resilient; other days, it stings and throbs with the full pain of thawing.

But it is not a corner I’d painted myself into, it is an open room where I can forgive, and embrace the girl I was, because I know that the only people to blame for her pain are the people who abused her. And I hope that somehow, someday, Chrissie Hynde finds that room.