FADE IN AMSTERDAM, JUNE 30

There are giggles coming from Beck Hansen’s dressing room at the Melkweg arts corner. Given the rafts of weed and hash that flow through the canals and “coffee shops” of this ridiculously accommodating city, preshow bouts of goofy euphoria commonly go unnoticed. But instead of getting small, Beck and his gorgeous backstage playmates are going through growth spurts. Cosimo, Beck’s four-year-old son, is crazy talkative and has more bounce in his step than a Timbaland bass line. Beck’s daughter, Tuesday, barely one, is still all gurgles, but she made her Berlin stage debut a week ago, her tiny eardrums protected by massive cans as she crawled among the monitors while Dad powered through “New Pollution.”

Beck is experiencing new sensations, too. Modern Guilt, his 11th album, is days away from release. It’s the final record in his deal with the Universal Music Group—a business relationship that has endured for 14 years—and his future as a slicing-and-dicing track master, popping-and-locking showman, and icon of cultural cool is emphatically up in the air. At 38, Beck is more than a decade past his smirking commercial peak—1996’s double-platinum bricolage masterpiece Odelay—but arguably in only the earliest phase of his emergence as a mature songwriter and recording artist. Coproduced by Beck and Gnarls Barkley soundscaper Danger Mouse (a.k.a. Brian Burton), Modern Guilt percolates on the surface with sonic pleasures but haunts subliminally with a very dark portrait of paranoia, weariness, and societal ills.

Riffing on cultural crises is one thing, but when a musician’s eyes finally open to the absurdities of the road, you know he’s taking the measure of his life. And only two weeks into an eight-week tour of Europe and the U.S., Beck has had it with the bus. “It’s like sleeping on a washing machine,” he says, bleary-eyed. He’s just rolled in from Zurich, Switzerland. Tonight, post-show, he and his family, his two nannies, his band, and his road crew will drive, and ferry, and drive some more to Southampton, England. Their sprint last week, from Arendal, Norway, to Berlin, was a brutal 25 hours. “My son got bounced all around the bus,” Beck says.

Also Read

30 Overlooked 1994 Albums Turning 30

In even a remotely funny way?

“No.”

LOOP #1 / BECK / QUOTE

“I was popping into people’s studios all the time [in the early ’90s], recording different tracks. When the guy from Bong Load [Records] called to tell me they were releasing ‘Loser,’ I don’t think I even had a copy of it; that’s how long it had been since I recorded it. Then a major label in New York, which I won’t name, called and said they wanted to meet me. I didn’t want to go. But a friend said, ‘Why not? They’re gonna pay for your ticket!'”

SCRATCH VOCAL #1 / COLLABORATOR

SPIN: Is Beck’s working method similar to that of other artists—Gorillaz, MF Doom, the Black Keys—you’ve collaborated with?

DANGER MOUSE: In certain ways, but different in others. He can write songs so fast. It’s something I wasn’t used to.

SPIN: Did that surprise you? Did your respect for Beck grow?

DANGER MOUSE: Absolutely. It’s not to say that I didn’t have respect for him going in. But watching him work the way he does…[As a producer], I’m always feeling pressure to figure out “How the hell is this going to work?” And before you knew it, he had the solution. And I’m just watching, astonished, and going, “Okay, that’s why you’re Beck.”

REWIND ZURICH / JUNE 29

The place looks as if it seats 100, but there are only six of us here. Somewhere on the other side of majestic Lake Zurich, 45,000 schnockered locals are crammed onto the waterfront boulevard Fanmeile (Fan Mile) to watch the 2008 European Soccer Championship final on three mammoth video screens. No wonder there are so few of us tucking into the langoustine ragout with lemongrass sauce at the divine lakeside eatery Riva Fish Inc., with its stunning night view of swaying sailboats and luxe mountainside homes.

Beck, who hasn’t a care or a clue who is getting their kicks tonight on the soccer pitch, does the monkfish and gazpacho—the latter, he’s been assured by a friend, will act as a coolant on what has been a stultifying day in Switzerland. Not even the boat ride he, his actress wife Marissa Ribisi, and the little Hansens took hours earlier could cut the heat. “The kids were, like…” Beck makes a low groaning sound. “Let’s just hope there’s no heatstroke.”

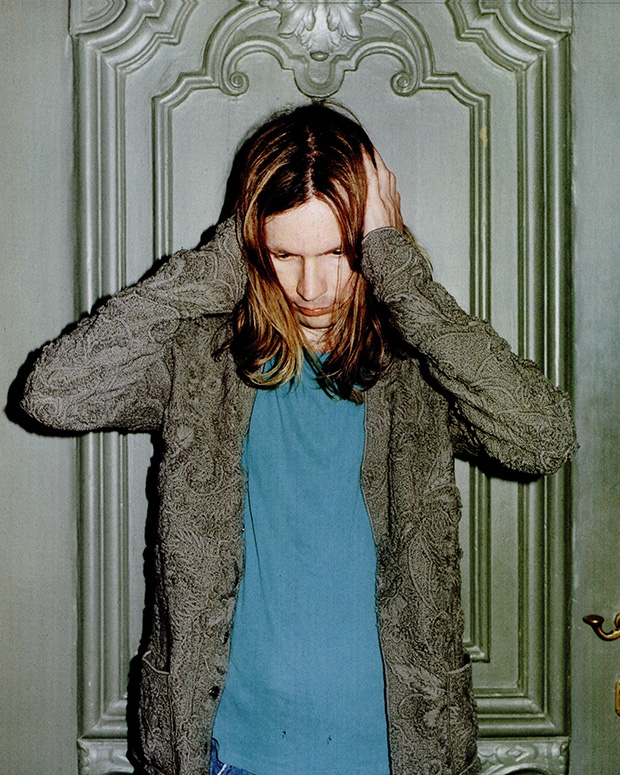

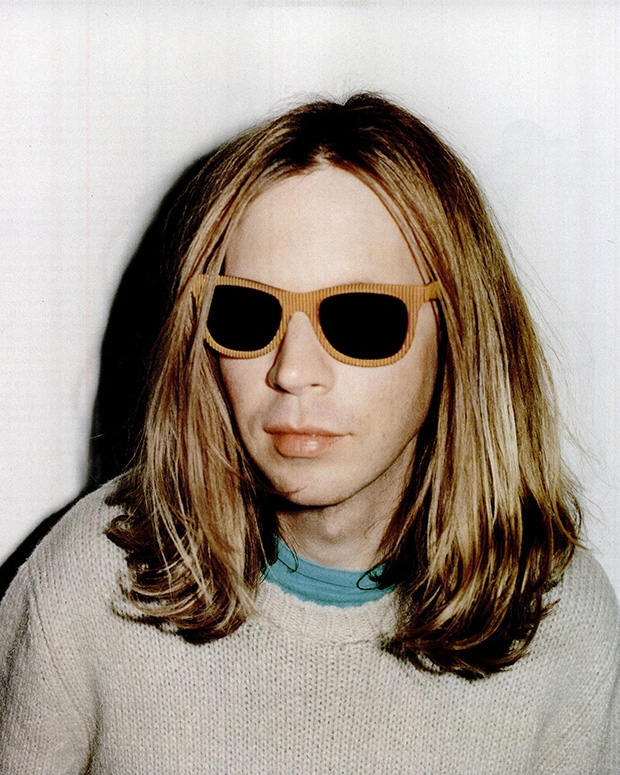

If you didn’t know better, you might think that’s exactly what has zapped Beck’s energy tonight. “Low-key” doesn’t quite describe his vibe; that would suggest he’s a warm-bodied presence. In fact, he’s more of an essence—there but not there, friendly but remote, in the flesh but somewhere in the clouds, too. It suits his ethereal looks, which are still long and lean and striking, even if his Huck Finn features, now framed by shoulder-length locks, have yielded to faint age lines, dense stubble, and an unexpected crop of chest hair.

“I was going for 30, but I would have loved 28,” Beck says about the running time of Modern Guilt, which clocks in at a fleet 33 minutes. He’s the kind of conversationalist who takes in your questions with expressionless eyes, then looks for his answers somewhere over your shoulder. “A lot of my favorite records are around 28 minutes. Rubber Soul. Pink Moon. It wasn’t really conscious, but I like giving myself a challenge. ‘What can I say in 30 minutes that doesn’t need to be said in 50?'”

PUNCH-IN AMSTERDAM

“I hear it’s very short, but good!” says a breathless young Israeli about Modern Guilt, outside the Melkweg three hours before showtime.

“And I hear it is a return to form!” squeals his new BFF, a Netherlander in shorts and a blazer. “It starts quiet and gets psychedelic. Just like Beck!”

REWIND ZURICH

The decision to collaborate on Modern Guilt with Danger Mouse dates back several years. “When The Grey Album came out [in 2004], I thought, ‘I’d like to work with this guy,'” Beck says. “I didn’t know anything about him at the time. But we started running into each other in L.A. [Late in 2007] I called him and said, ‘I’d like to work on something by the end of the year.’ But he only had one day available, because he was finishing the [second] Gnarls Barkley record. So that day we did the first song on the album, ‘Orphans.’ And then he said, ‘You know, tomorrow I can come by, too.’ And the next day we did ‘Gamma Ray.’

“I think in January he told me he had two weeks. And I thought, ‘Well, if we did two songs in two days…’ So we got together again and did a lot of songs, 15 or 16 really quickly.” That number grew to 30 or 35. Only ten are on the record.

LOOP #2/BECK/QUOTE

“So I went, and I met with these two executives in some high-rise in Manhattan. They sat me down across from this big desk and, out of these huge speakers, blasted my own song right at me. You know how these guys do—they started bobbing their heads to the music.”

DATA COMPRESSION NIELSEN SOUNDSCAN

YEAR TITLE COPIES SOLD

1994 Mellow Gold 1.2 MILLION

1994 One Foot in the Grave 168,000

1994 Stereopathetic Soulmanure 92,000

1996 Odelay 2.2 MILLION

1998 Mutations 587,000

1999 Midnite Ventures 743,000

2002 Sea Change 679,000

2005 Guero 867,000

2005 Guerolito 76,000

2006 The Information 432,000

2008 Modern Guilt 84,000*

*First-week figure

CROSSTALK ZURICH

SPIN: Your contract with Interscope gives you complete creative control, but did label executives express excitement that you were working with a hitmaker like Danger Mouse?

Beck: I never heard a word, but I’m sure they weren’t angry. But the fact that somebody makes hit songs, that’s not what attracts me to them.

SPIN: Was there any commercial consideration in choosing Danger Mouse? He’s not the kind of producer you’ve chosen to work with in the past.

Beck: Well, in ’98 I was gonna work with the Neptunes. I’d just recorded Midnite Ventures and was listening to the first stuff they were doing. But I took a few years off, and by the time I came back, they’d become the producers, and for that reasons I thought our musical collaboration wouldn’t be pure. When [Danger Mouse’s multiplatinum] Gorillaz record came out, I thought, “Maybe it’s the same thing, again.” But after he and I met and hung out, I decided I wasn’t gonna second-guess it.

SPIN: Do you feel pressure to make hit singles?

Beck: I don’t. The songs that were successful weren’t intended to be. It’s weird. With Odelay, I thought we were doing something experimental.

SPIN: What was going on in the culture at the time that made that album a hit?

Beck: I have no idea. I mean, maybe it was so different from what was prevalent at the time. You know, we were coming off of six or seven years of homogenization, that ’90s rock sound. I think it got acceptance by default.

SPIN: Aren’t you undervaluing its boldness?

Beck: Well, it definitely had energy and that threads-hangin’-out kind of sound. But part of it was just ineptitude, and the other was trying to avoid certain things that, when I started out, I just considered bad taste. Certain beats, drum sounds, guitar sounds. But that album sat around for six months or longer. I had many people tell me that it wasn’t good and would be a mistake to release. But at least I went out and did something interesting, instead of trying to re-can “Loser” ten times.

SPIN: So what happened?

Beck: When the reviews came out, I got an incredulous call from my tour manager: “Have you seen the reviews?!” After Mellow Gold, I stopped reading them, and I said, “Are they awful?” He went, “No! They’re saying it’s a great record!” I was shocked.

SPIN: How did—

Beck: I’m sorry. I’ve gotta catch a bus.

HARMONIC DISTORTION #1

-Beck and family’s bumpy overnight travel time from Zurich to Amsterdam by tour bus: 12 hours.

–Spin reporter’s travel time from Zurich to Amsterdam by Boeing 737 (after a sweet night’s sleep): one hour, five minutes.

HARMONIC DISTORTION #2

“BECK, RIBISI BUY $7 MILLION L.A. HOME”

—People.com, November 12, 2007

RETURN AMSTERDAM / MELKWEG

As dressing rooms go, it’s the usual dump—complexion-draining overhead lighting, mismatched furniture, walls the varying shades of Amsterdam’s green-gray canals. Beck is sitting quietly at a table scattered with food. Absently, he dips his sweater sleeve into a smear of preserves. A drag, for sure, but he doesn’t even bother to wipe the sticky blob off the table. If his energy was low last night in Zurich, it’s not even metering tonight. The sleepless bus ride, a Spin photo shoot, a hernia he’s been nursing since a harness-stunt mishap on the set of a 2004 video shoot, all have him blanched. Ironically, he’s eyeing tonight’s set list to make sure there aren’t too many slow tunes. Otherwise, he says, the audience “ends up at the falafel hut.”

This time around, Beck is touring with a stripped-down new band and stage show, in part because it suits the leaner masculinity of the new songs, in part because it’s what he can afford. The puppet shows and Nudie suits and horn sections of the past? “Well,” he says. “I usually spend my money trying to make the shows interesting, and I end up not breaking even sometimes. These days, it’s just ‘Get up there and play,’ and that’s all that’s important.”

Despite his stature as one of the most electric, forward-thinking, and prolific rock stars of the past two decades, Beck, at his core, is an artist with the DNA of a bohemian, a feverish noodler who’d have to make art regardless of business considerations.

He chuckles nervously. If he had his choice, “none of it would be a business consideration,” Beck says. “I mean, I’ve already blown most business considerations. I can’t tell you how many opportunities I’ve turned down.”

Like commercials? “Oh, yeah. Most people I know don’t think twice about it. It sounds stupid, but it’s just not the reason I started making music. It has to ultimately be something that is for the sake of creative effort rather than pure business. Maybe that’s because I came of age in the ’80s and saw so much commercialism. It was disgusting to me. So I’ve always tried to avoid it.

LOOP #3 / BECK / QUOTE

‘When the song [‘Loser’] was over, one of them said, ‘We think you’ve got something here. It’s gonna need work, and we can help with that. We’ll also have to change your image a bit. But if you do those things, maybe we’ll be able to work with you.’ I looked at them and said, ‘Goodbye.'”

CROSSTALK AMSTERDAM / MELKWEG

SPIN: You came from a family of artists. Your grandfather Al Hansen was an influential but scuffling player in the Dada-like Fluxus art movement of the ’60s. Your dad, David Campbell, was for years a sideman in L.A. How did it feel to be a person following those same creative impulses but suddenly making a lot of money doing it.

BECK: My record deal wasn’t such that I was living high on the hog. Even after Odelay, I was still in a tiny two-bedroom house. It’s funny, my tour manager will say, “Yeah, I worked with them. They have a jet.” And I’d be like, “Really? That person has a jet?” Seriously, you’d be shocked. But they’re just better at business. It’s not my strong suit, at all.

SPIN: Were you upset, then, when People reported on the $7 million home you bought last fall?

BECK: Yeah, well, I don’t really own that. When you buy a house, you make a down payment, and…actually I’m selling it because I don’t have the money to live there. I feel stupid talking about this stuff, but even if I sold everything I own, I don’t have near that much money.

HEAD REALIGNMENT

In lining up dates for the Modern Guilt tour, Beck turned down an opportunity to play his first-ever headlining gig at Manhattan’s 19,500 seat Madison Square Garden. His current show, Beck thought, was “just not right” for the space.

CROSSTALK AMSTERDAM / MELKWEG

SPIN: Have your priorities shifted now that you’ve got a family? Isn’t touring antithetical to that life?

BECK: I don’t know. I don’t think I work any less with having a family. There are times that I wish that were the case. But I’m like anybody; I have to work. You give as much as you can to your children, but I’m in no position to stop everything I’m doing.

SPIN: Did you always want kids?

BECK: Oh yeah. For years.

SPIN: Do you take something away when you see the joy and spontaneity in them?

BECK: It becomes acutely apparent that you’re the grown-up! [Laughs]

SPIN: Do you encourage them to make art?

BECK: They just do their own thing. I thought when you had kids that there were all these things that were gonna happen: tell ’em about this or that, sit them down and play them music and show them what art is all about. But they come out singing. Before he could talk, Cosimo had his favorite songs. And they weren’t songs I played him.

SPIN: Like?

BECK: He loves Joanna Newsom and Gnarls Barkley. And “Splish Splash (I Was Taking a Bath).”

HARMONIC DISTORTION #3

“According to Duncan, sometime in their two-year acquaintance, Beck expressed to her and Blake a desire to leave the church, and they had offered him encouragement and even assistance. ‘That’s ridiculous. Totally false,’ Beck said. ‘Had we been closer and discussed anything as personal as religion, I would have only had positive things to say about Scientology.'”

—From “The Golden Suicides,” Vanity Fair, January 2008

PATCH-IN SCIENTOLOGY

I asked a friend, a Beck fan, if she had a questions he wanted me to ask him. She e-mailed me this: “Why are you a crazy Scientologist when you seem like such a smart fella?”

Until the early aughts, Beck had managed to keep his lifelong connection to the Church of Scientology fairly private. For many people, the queasiness of that affiliation to an organization routinely reported to be a ruthless cult doesn’t quite square with Beck’s cool, which got tested big-time with the suicides last July of artists Jeremy Blake and Theresa Duncan. Introduced to Beck by filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson, Blake—a pioneering digital painter—was recruited to create the cover art for Sea Change. Sensing an opportunity, Blake’s girlfriend, Duncan, passed Beck a script called Alice Underground, which she was hoping to turn into her directorial debut. He read it as a favor, though at that point he’d turned down many screen offers. As Duncan’s project unraveled, she and Blake became paranoid that they were being stalked and professionally sabotaged by Scientologists. Beck, Duncan claimed to friends, had confided that he was desperate to break from the church but terrified to do so. Duncan’s punishment for making this public was, she thought, the source of their trouble.

After a year of spiraling hysteria, Blake and Duncan left L.A. for New York, where her unexpected suicide by overdose led her shattered lover, a week later, to walk naked into the Atlantic to his death.

There are only two things in our conversation that make Beck barely audible: talk of his relationship with his wife, whose family has deep roots in Scientology, and any discussion of the church itself—not that he’s unwilling to go there in that sort of Teflon way with which Scientologists have been known to tackle such questions.

SPIN: What has it been like to have so much press devoted to your spiritual life?

BECK: I don’t pay attention to any of it, really. I’m not that aware of what the perception is. My father was doing Scientology in the ’60s, so it’s something that has been around for most of my life. But the only time I hear anything negative about it is in interviews. In the real world, people I know, they don’t give a shit. I was raised celebrating Jewish holidays, and I consider myself Jewish. But I’ve read books on Scientology and drawn insights from that.

SPIN: Was there a time when you tried to keep it on the down-low for career purposes?

BECK: No, I don’t think so. There were years when I wasn’t involved, but it didn’t mean that it wasn’t a part of what I grew up with.

SPIN: Were you blindsided by the Jeremy Blake and Theresa Duncan story?

BECK: Absolutely. That was out of nowhere for me. I knew Jeremy briefly…I literally met him for a half hour [to discuss the Sea Change cover]. And he came in a couple of days later with about 20 or 30 ideas, and they were all great.

SPIN: That was your total engagement with him?

BECK: I saw him maybe four or five times socially after that. I didn’t really know him well.

SPIN: How seriously did you consider Theresa Duncan’s script?

BECK: I’m not an actor. But he was a friend, and so I read the thing and liked it. But I’d been offered everything from High Fidelity to a John Waters film, and I just turned it all down.

SPIN: Has the belief system of Scientology been a crucial part of your partnership with your wife?

BECK: You know, it’s books; it’s not a belief system. It’s only true if it’s true for you. That’s the way anything is. With my wife, I think…you respond to a person as a person. It’s not based on anything other than two human beings. We’re just like anybody else, working and trying to raise a family.

PITCH ADJUSTMENT ZURICH

When Beck signed his deal with Universal (which started him on Geffen, then moved him to Interscope), he was guaranteed the right to also release music on smaller, indie labels. It only briefly worked out that way. Now it’s at the point of leaving the company that he can open the floodgates if he wants. Does he envision reupping with a major or going the Radiohead or Nine Inch Nails route by, essentially, giving his music away to support a touring life?

Back at Riva Fish Inc., he can’t help but think of his loss of appetite for the road. “Even if I didn’t have a family, I’d have less of a desire to tour,” he says. “It’s something you can punish yourself with when you’re starting out. But after you’ve done eight or nine albums…. To do it, you’re either a machine or on drugs.

“I don’t know,” he continues. “I don’t make predictions because things change so much, but this is probably my last tour. There’s a point when it becomes apparent that it takes away more than it gives. There’s probably a lot of other jobs I’d rather do to support my family.”

As for another major-label deal, it’s doubtful. “Beck is definitely excited about going indie,” says someone close to the artist. It’s unclear if Interscope offered to extend his contract, but label executive Steve Berman is both obsequious—”Beck is very important to us; he’s done an incredible body of work for this company”—and a little stunned by talk of Beck’s indie aspirations. (“If Beck chooses to pursue, you know, an independent route—[long pause] I haven’t heard that directly, so I’m not going to comment.”)

According to Beck, the choice of a major-label deal might not even be up to him. “I may never make anything again that a major record company would want,” he says. “I mean I had to go play [Modern Guilt] for the European record company. They weren’t going to release it unless they heard the music first. I said, ‘Well, I’ve made other records.’ But I don’t think anything’s a given these days.”

FADE-OUT AMSTERDAM

So how will this play out? Quickly, for a reporter. Beck needs his rest before showtime. But for arguably the most imaginative cultural synthesist and record-maker of his generation?

“I have no idea. I know I’ll be working on music. I have some ideas of things I want to do, and I have a lot of things recorded, so I wouldn’t be surprised if I had a few things coming out sooner or later.”

In his downtime last year, Beck dived deeply into movie watching. Film directing, not acting, intrigues him. So he obsessively mainlined vintage flicks: tons of westerns (a fact that even he finds hilarious) and the entire filmography of the brooding Swedish master, Ingmar Bergman. Very heavy sledding.

“Yeah,” he says, “but Bergman’s stuff taught me a lot. Like patience: just the willingness to go with something, to suspend belief and surrender to the nonlinear. There are so many things in music these days that can desensitize you. I’ve been trying to avoid that and resensitize.” With what looks like his last flicker of energy, he fingers his sweater.

“Yeah,” he says softly. “I think that’s what’s needed right now. A resensitizing.”

BURN

Ninety minutes later, Beck and his scorching band bring the Melkweg down.