(This article originally appeared in the September 1994 issue of SPIN.)

It’s an early Wednesday evening in North Oakland, and the lead singer for America’s most popular new rock band is getting carded at the pizza parlor. He hasn’t gotten around to replacing his lost California driver’s license (though that doesn’t stop him from puttering around town in a classically Berkeley, moldering Ford Fairlane), but Billie Joe of Green Day really is over 21, though just barely. For a moment, I wonder whether I’ve got their press kit in the car with me — has a photocopied photo-feature from Entertainment Weekly ever been successfully presented in lieu of valid ID?

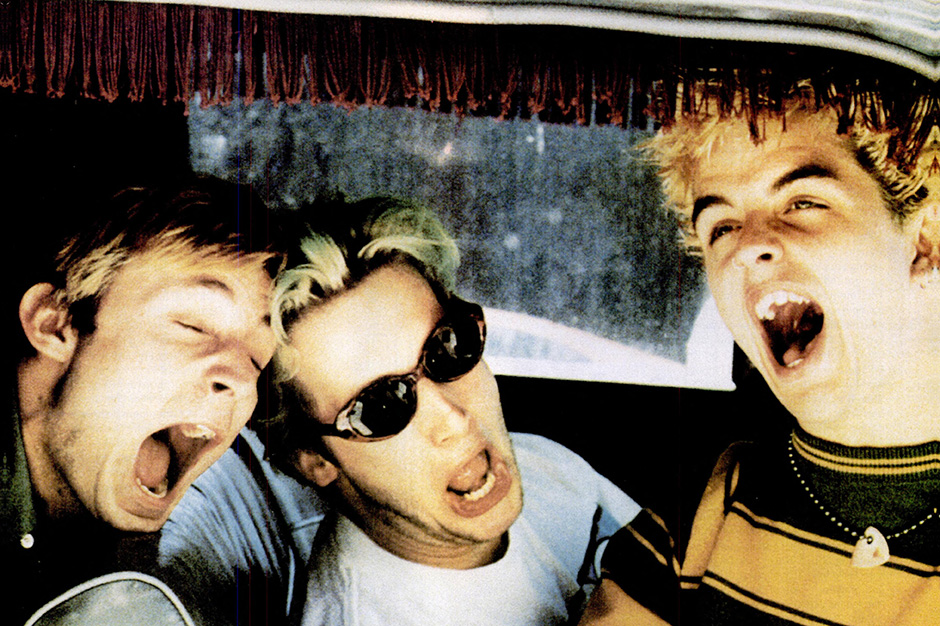

Not that the woman behind the counter is feeling generous. We’re at an upscale place, famous locally for its deep-dish slices, on the rather genteel College Avenue in Rockridge. With their dyed, crunchy hair, sub-5’8″ bodies, and baby faces, Billie Joe and Green Day drummer Tré Cool look a bit too Telegraph Avenue for her taste, like punk street kids who wandered in from begging near U.C. Berkeley. Bassist Mike Dirnt, whose stoned, sleepy demeanor and taller frame make him the one member of Green Day who looks older than he actually is, has already quietly secured his beer and gone off to a corner. Meanwhile, Tré and I can’t help slipping Billie Joe a few sips as we wait by the window for our take-out pies to arrive.

Suddenly, the same woman is back again, still taking in that by-the-manual tone punks hate almost as much as they do cops and hippies. “I’m sorry, but we’ll have to ask you to leave now. We could get shut down for a code violation.” Billie Joe doesn’t say anything. He just grabs my glass mug, takes one more deep gulp, and then spits the whole thing out high up the window. I watch a parabola of Red Hook and saliva descend down the glass, as Billie Joe’s out the door. When a guy in an apron appears to wipe up the window, Mike leans over to him and, ever the sidekick, remarks: “I’m sorry you have to clean that up, but I can’t say I think what he did was wrong.”

A certain level of controversy, always faintly ridiculous, seems to accompany everything Green Day does. A few days before, I’d seen the band play “BFD,” a modern-rock showcase hosted by San Francisco radio station Live 105 at the Shoreline Amphitheatere. On that rarest of Bay Area days, a 100-degree scorcher, Green Day appeared third on the bill, at 3:30 in the afternoon, after a dazed and heat-struck Beck. The amphitheatre, which seats about 20,000, quickly went from half-empty to almost full — much like when Pearl Jam played second at Lollapalooza there in 1992. The crowd wasn’t punk in the least — over the course of a nine-hour day I spotted one guy in an MDC shirt and felt sorry for him — but its enthusiasm for Green Day exceeded anything the other ten bands playing could have hoped for. Before too long the high school kids, piled onto the lawn in back, were moshing like water over a sandbank.

And who could blame them. There’s something that can’t be equaled about seeing people almost exactly your own age getting to be real live rock stars. The members of Green Day have become rock stars in an eyeblink; their third album, Dookie (the first for Warner Bros. after two on the indie label Lookout), has risen to No. 31 on the Billboard album chart after MTV Buzz Bin airplay for the video “Longview.” At Shoreline, Green Day played the part to perfection, headbutting the microphone, shredding flowers, darting around in shorts like a baby AC/DC, tossing out snotty banter (“I hope you guys are beating the fuck out of each other and go home with fucking bruises,” said Billie Joe), and just plain acting as if throwing out loud rock music on a hot day was what life was all about. During “Longview,” a song about masturbating bored in front of the television, Billie Joe had whipped out his dick and shaken it around during the line, “I’m feeling like a dog in heat.”

Later, during a day when bands were playing half-hour sets and then retreating with mechanical bows, Green Day refused to come offstage. Maybe it was problems with the sound, or maybe Green Day just isn’t happy without a little conflict. It did feel a bit rote, hearing the band vamp while roadies whispered threatening things into Billie Joe’s ear, and the singer suggested to the crowd, “Now that they’re angry at us, we could rip out the seats.” Still, even coming off a grueling European tour, with no day off in between, Green Day’s enthusiasm gave an empty show its only feeling of common purpose.

Proud boomer Gary Kamiya was less impressed in the San Francisco Examiner, writing “It’s hard to know what to make of a bunch of 22-year-olds who want to play roots punk. They did the primal Sex Pistols/Clash style of punk very competently, complete with impressive vertical leaps by the bassist, a guitar slung at an unimpeachably low level, and the requisite petulant outbursts. But why?”

Well, to get out of Rodeo, for one thing. A town outside of Berkeley, once described by Green Day’s singer as “white trash and hicks,” Rodeo simply isn’t on the map of Bay Area culture. Billie Joe — I asked him his real name; “None of your business! First name Billie! Last name Joe!” — is the youngest of six children raised there by a waitress mom; his dad, a jazz drummer and trucker, died when he was ten. His childhood friend Mike Dirnt, with whom he began playing music at the age of 11, comes from a troubled situation himself; he moved out on his own at 15.

Billie Joe left home, too, at 17, and he lived on couches and in a scary live-work band space. He once lived in an old brothel and hotel, located on a desolate block in West Oakland under the BART trains. I remember seeing a show there some years ago: It was like discovering the slacker version of New Jack City. West 7th Street would be commemorated on one of Green Day’s best songs, “Welcome to Paradise” first recorded for the band’s 1992 album, Kerplunk, and then redone for Dookie.

But even before leaving home, the two had found paradise: an all-ages, all-volunteer club located on and named for Gilman Street in Berkely. The center of Bay Area punk life, Gilman attracted an international cult in the late ’80s, as an example of DIY at its best. Led there by Billie Joe’s “more cultured” older sister Ana, Dirnt and Billie Joe would go from being fans hoping to cadge enough money to get in the door, to performers (under the name Sweet Children at first), to signing a deal with one of the scene’s most respected labels, Lookout. Their first record, a four-song seven-inch, came out in 1989, before either had turned 18. The suburbanites had fully entered a community they still speak of in reverent terms today.

“There’s so many people that work there,” says Billie Joe of Gilman. “And there’s things that people have done that SPIN magazine couldn’t understand. You can’t even explain what their place has done for the music and culture of the Bay Area.” Tré Cool: “Gilman doesn’t even want the press.” Dirnt: “It’s like trying to describe being a stripper without ever being a stripper.” Billie Joe: “There’s something religious — I mean, there’s people who come from all over the world that come to that place and find some kind of —” Tré Cool, half jokingly: “Punk-rock mecca.” Billie Joe, not joking at all: “Yeah.”

“We’ve played in front of 20,000, 30,000 people,” says Billie Joe, “and I still haven’t felt the same thing that I felt playing in that place. There are bad shows I’ve had there that I’ll remember for the rest of my life, and there’s the greatest shows I’ve ever played. An gone to.” Dirnt: “The best shows I’ve seen in my life. Operation Ivy.” Billie Joe: “Neurosis.” Dirnt: “Neurosis, oh my God.”

It wasn’t only Gilman, of course, but the feeling of being a part of such a closely knit scene. Tré, who played drums at the age of 12 in the Lookouts with his Mendocino neighbor, Lookout Records boss Lawrence Livermore, before joining Green Day at the time of Kerplunk, remembers a show in someone’s one-bedroom apartment: “The bands are crammed into the kitchen. They grabbed a space heater and threw it out the window so somebody could stand where the space heater was.” “When you’ve gone to one of those shows,” says Billie Joe “it’s almost next to godly.”

I press for details — names of bands, ‘zines, whatever — and the mood starts to stiffen. The band starts talking about “punksploitation,” and the way undergrounds lose their personal nature upon reaching the public eye. Billie Joe is about to lose his temper, and I have no desire to revisit the pizza parlor.

“Can we talk about something else besides the underground?” he asks.

Why, sure. How about the costs of major-label success? For a band like Green Day to make it big is somewhat different from Nirvana, the Breeders, or many of the other indie rock-gone-“alternative” acts of the last three years. Despite their often Beatle-esque and quite clean power pop sound, Green Day comes out of what those within it call the punk scene, and I’ve always thought of it has hardcore. Punk, of course, splintered in all directions; into clannish college bands, arty disco, whatever. But the mantle of punk has always been claimed by new generations of scabily dressed kids with a completely uncomplicated view of noise as rebellion.

Since the A&R people at major labels share the more elitist tastes of the indie-rock breed, it’s been rare until now for bands who developed their popularity within the all-ages punk circuit to get signed. The irony, however, is that hardcore’s popularity has always dwarfed indie rock’s; a far wider range of people enjoy it than the more twisted taste preferences of the indie scene. Recently, with not only Green Day but also punk bands on Bad Religion’s Epitaph label like the Offspring and Pennywise, the music industry has started to discover this truth for itself. The signing blitz is on. So for the punk community, Green Day really is the next Nirvana — harbinger of dramatic changes to come.

Not surprisingly, the scenewide furor that has resulted combines the brutal energy of hardcore with all its lack of clearheadedness. Most inexcusably, at Gilman Street in May, former Dead Kennedys singer, Jello Biafra, was assaulted repeatedly and seriously injured by a punk kid while a crowd chanted “sellout” and “rock star.”

Meanwhile, the June 1994 issue of the Bay Area ‘zine Maximum RockNRoll came out with a showing a man putting a gun in his mouth. “Major Labels: Some of Your Friends Are Already This Fucked,” the headline read.

Inside, far more comments were directed at Green Day than Kurt Cobain. The accusations were numerous; that no one on a major label could be considered “independent” or “alternative”; that the success of Green Day exploited the volunteer labor of people within the scene; that “each band from the punk scene that signs to a major label has sold us out,” particularly bands like Green Day, who by selling 50,000 copies on an indie label like Lookout could support numerous other bands with the profits; that, in the words of Brian Zero, organizer of an anti-Green Day protest in Petaluma, “if they want to call a band like Green Day ‘pop-punk,’ we can call Green Day the next Billy Idol.” Only Lawrence Livermore really stuck up for the band, resigning his MRR column and writing, “Fame is a powerful drug, and I don’t think it’s a wholly bad one.”

These matters have to be addressed, so I bring them up again upstairs, and the dangerous edge returns to Billie Joe’s voice. “Tim Yohannon [MRR‘s fanatical leader] can go and suck his own dick for all I care. He doesn’t know what the fuck he’s talking about. I’ve never waved a punk-rock flag in my life.”

Tré, giggly stoner that he is, tries to undercut the tension. “Hey, we finally got on the cover of MRR.”

Green Day says it needed to jump labels. Its popularity was creating jammed shows on the all-ages hardcore circuit, often ending up shut down by the police. Billie Joe is vehement. “If we’d stayed on Lookout, we’d be making more money than we’re making on Warner Bros., because that’s the kind of relationship we had with Lookout. And still have. It was more just a matter of distribution and a change of pace.”

The members of Green Day deny caring about what Maximum RockNRoll thinks, but then they start talking about Kurt Cobain, with whom they clearly identify; and all the frustrations of a success of their own community won’t allow them to enjoy come pouring out. “Can you imagine,” demand Billie Joe, “what is feels like to pick up that magazine, something you totally respect, and read all these fucking opinions about you? Of course you’re gonna be a manic-depressive. Because you’re either totally high or someone’s totally shooting you down, thinking that you’re a total dick. A fucking god or a fucking asshole. If they think that in any way major labels are partly responsible for the reason Kurt Cobain blew his face off, I think they were partly responsible for that too.”

“Putting him on a pedestal,” chimes in Dirnt. “If you want to be a regular guy, all of a sudden people just assume that you’re an asshole ’cause you’re rich or something, or they love you for it, you know? You can’t be modest and play music. To some extent he’s like Jesus to me. He died for my sins…so I could sign to a major label?”

Toking from a bong before we got started, or ripping up that couch in the “Longview” video (filmed in the tiny apartment Billie Joe then shared with friends), Green Day is basically the latest version of rock’n’roll’s favorite heroes: fucked-up adolescents making their bid at a rebellion that’s partly heroic, but also laughably juvenile. For an eternity, the new bands taking this stance were mostly metal; in this context, it isn’t surprising that one of the “classic albums” Billie Joe lists for me is Mötley Crüe’s Too Fast for Love, or that Green Day is known throwing trashy metal covers into its set.

//www.youtube.com/embed/FWvKSPQ9p5Q

I went back and listened to a couple of old Lookout records, one by Operation Ivy, another by Crimpshrine. A glimmer of the energy Green Day loved is buried deep within the vinyl — but you really had to be there. With Green Day, you don’t; you just have to prefer that your rock idols be people who were. More or less regular guys gain celebrity now, instead of those ’80s monsters of rock.

After Billie Joe was kicked out of the pizza place, I took him next door to a supermarket to buy him that beer. He told me he’d once worked in front of the store, selling newspaper subscriptions. We talked about Adrienne, his punk-rock girlfriend. They first got together four years ago, but for much of that time Adrienne has lived in Minneapolis; the separation has prompted such Kerplunk songs as “80” and “200 Light Years Away.” At the Shoreline Amphitheatre, Bille Joe signed autographs for his new fans, then walked backstage with Adrienne, two kids holding hands.

After the interview, I headed out to West Oakland, needing to see the “Welcome to Paradise” crash pad once again. Last time I was there it was to see my roommates band, Corduroy, which had just formed and which still tours the country playing shows that sometimes net them just six or seven dollars. (Plus beer, lots of beer.) It’s an old story in rock, where no one is created equal. I arrived at West 7th and Peralta, but of course there’s nothing to see now. Just an empty-looking building in a desolate neighborhood, with a sign over the door. “VALVA REALTY, FOR SALE.”