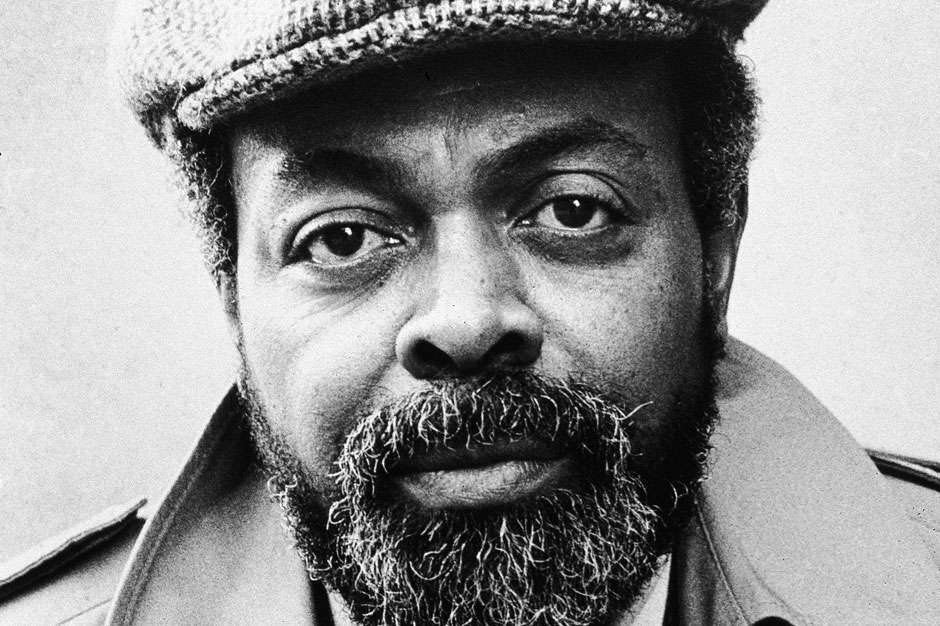

Writer, poet, playwright, activist, music critic, and walking bullshit-detector Amiri Baraka died yesterday at the age of 79. Most of the cranked-out obituaries thus far feel comfortable appending backhanded compliments like “polarizing” or “controversial” or “embattled” to their headlines, a glib misinterpretation of a complex and knowing artist. Perhaps he would have been bemused by these tricks (certainly he wouldn’t be surprised), but it’s heartening to imagine instead that he’ll return someday to drop some harsh words — inspired by both the poetic tradition and a game of dozens, which, as, Baraka himself showed us, was its own kind of poetic tradition — on a still-clueless mainstream.

Born Everett Leroy Jones in Newark, New Jersey, he began his career as in the beat poet mode (as Leroi Jones) and helped found the Black Arts movement, which was essentially the arts wing of Black Nationalism. He changed his name to Amiri Baraka in 1968; by 1974, frustrated by what he perceived as the limiting qualities of Black Nationalism, he’d embraced Marxism. These ideological shifts, used against him by those who preferred things to be just one way for all time (though nothing is), represent Baraka’s persistent search for truthfulness and accuracy — ideals that his work revealed to be always unstable and up for grabs.

When surveying Baraka’s career, things get tense once you move past his “greatest hits,” so to speak: His most celebrated works tend to soothe conventional liberal and academic attitudes. He established himself in the ’60s out of a frustration with positivist clap-trap like “the canon” and “good taste,” but was still immediately absorbed by a neo-canon that codified real quick and tended to dismiss his later, more emboldened works. So don’t forget to investigate stuff like 1982’s New Music – New Poetry, 2003’s The Essence of Reparations, and 2006’s Tales of the Out & Gone.

On to those greatest hits, though. 1963’s Blues People: Negro Music in White America is an explosive volume of jazz criticism, expressionist history, and, in its own way, wide-eyed memoir, staring white supremacy down and presenting its ins and outs logically (making them all the more disturbing) while asserting that the American form of slavery, which helped birth the “negro music” whites love so much and too often pretend is their own, was a particularly insidious and alienating strain of an operation Africans were hardly strangers to experiencing. Its confident thesis — that the roots of so much music deemed “American” goes back to Africa — is one of those intellectual smart bombs that seems apparent and obvious now only because Baraka’s book was so clear-eyed and on-point.

Also Read

Compact Discs: Sound of the Future

And I can’t be the first to have pointed this out, but it’s funny how the literary establishment was okay with something like his 1964 Obie-winning The Dutchman — a play about a white women slowly dissecting a black man’s ego on the subway, ending with the white woman stabbing the black man in the heart — but became far less comfortable with Baraka’s later work, which was more about the oppressed enacting violence on the oppressor. Think something like his 1965 poem “Black Arts,” a staccato manifesto about what poems are (“Poems are bullshit unless they are teeth”) and what he wants them to be: “Poems that wrestle cops into alleys and take their weapons leaving them dead with tongues pulled out and sent to Ireland.”

Baraka’s 2002 poem, “Somebody Blew Up America?,” about the September 11 attacks, was a rabbit hole dive into our nation’s ugly history of exploitation and abuse that located the United States’ culpability in so-called “terrorism,” over and over again. A mobius strip of corruption and hate, it’s punctuated by the loaded question, “Who?” which it never entirely answers, either because the answer is self-evident, or because it’s too knotty to fully extract and stick in everybody’s dumb, xenophobic faces. That it would be attacked for its supposed racism in the midst of real-life policies enforced to vilify brown people all around the globe is precisely why speaking one’s mind — and letting it all out via smart, fearless art, warts and all, racial epithets included, with iffy conspiracy-theorizing and then some — is vital. And given Baraka’s reputation as a rhetorician comfortable with violence and even hate, his life-long ideological searching suggests someone indefatigably optimistic about life’s possibilities. You don’t remain so razor-sharp and daring for so long if you’re cynical.