There’s something inscrutable about Janelle Monáe. Speaking with the 27-year-old, Kansas City-born musician, it can be difficult working out whether her intense self-assuredness is simply part of her magnetic cabaret, or something more. She talks quickly, with intent and poise, and comes off as thoughtful and serious — quite the opposite of the fun-loving weirdo seen in her new video for “Dance Apocalyptic.”

Talking over the phone,she barely deviates from the autobiographical factoids that make up her public narrative: her working-class roots, her commitment to individuality, her artistic independence. (She’s signed to Bad Boy, but Diddy hasn’t crashed one of her videos or obtrusively eh-eh‘d on a trackyet.) And, of course, there’s the mythology behind her albums, configured as discrete parts of a vast, inter-connected composition sketching the origins of her “DNA-sharing” muse/alter ego, Cindi Mayweather. (Suite One was 2007’s Metropolis EP; 2010’s The ArchAndroid delivered Suites Two and Three.) Really, the only mundanepersonal detailshe reveals is that she took a morning swim before sitting down to take calls at her Wondaland home/studio compound in Atlanta, and to discuss the latest installment of the Mayweather saga, The Electric Lady, out September 10.

“Has it been three years? It’s been that long?” She feigns surprise about the gap between full-lengths. “I don’t keep up with time like that, because I’m constantly working. It’s a release for me. I used to know when Monday was Monday and Friday was Friday, but I don’t even know.”

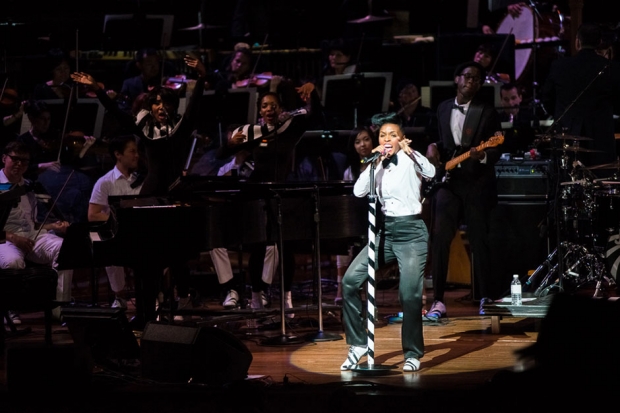

There’s something fascinating about Monáe’s commitment to her story. From the saddle-shoes-tux-pompadour outfit she favored almost exclusively while promoting The ArchAndroid (in homage to the uniforms worn by her blue-collar family) to the intricate character development of her android doppelganger/protagonist, her devotion to persona isn’t just a branding angle — it’s an example of how she views her entire being as an exploration of artistic freedom.

“Creative independence is my air, it is my water,” she says, citing her label/musical clique, the Wondaland Arts Society. It’s the home of Monáe’s inner circle of collaborators, including her primary creative team, the trio of Chuck Lightning, Roman Gianarthur, and Nate “Rocket” Wonder. Her records have borne the Wondaland imprint since her 2003 unofficial debut, The Audition; Bad Boy joined her, not the other way around.

“I definitely have been in a blessed position, to come into the industry really being in control of my artistry,” she says. “Wondaland was always moving units independently and, as we are right now, speaking directly to the people. This is honest, open, unfiltered music, and we’re blessed to work with people who have helped us move the underground above — so we have a bigger platform.”

With The Electric Lady, it’s apparent that Monáe aims to top The ArchAndroid, which rated high among critics, debuted in the Billboard Top 20, and landed her a 2011 Grammy Awards nomination for Best Contemporary R&B Album. It made her a name, but not necessarily a household one.

To get there, she’ll have to make sure all those households are up on her highly developed mythos. Before undertaking The Electric Lady, she requests you re-read the liner notes from The ArchAndroid, which in turn details the Metropolis plot: She’s actually from the year 2719, where her genomic sequence was stolen to create the famous archandroid Cindi Mayweather, before Monáe herself was forced back in time. That kind of yarn-spinning shows that she’s as much a devotee of science-fiction author Octavia Butler’s vivid Afro-futurism and Steven Spielberg’s crowd-pleasing fantasias as she is of more traditional R&B wellsprings. The beauty of her music is that it combines all those influences, tying narrative complexity to deep human emotion.

The new album’s funky, fragmented single “Q.U.E.E.N.” — featuring Erykah Badu and a 40-second, fist-in-the-air rap verse from Monáe herself — might be an unlikely candidate for radio play, but within a week of its release on YouTube, the video racked up almost three million views. That has a lot to do with the song’s repeated hook — “The booty don’t lie,” a life maxim if there ever was — but it’s Monáe’s chameleonic delivery that gets it over.

“With ‘Q.U.E.E.N.,’ I did a lot of questioning as it pertains to sexuality,” she explains. “‘Is it peculiar that she twerk in the mirror? / Is it weird to like the way she wears her tights?'”

Did those questions find answers? Monáe pauses, then eloquently evades the personal, as always. “A lot of what I say on this new album isn’t necessarily authoritative. It isn’t coming from, ‘This is how I experience these things.’ I’m merely posing the questions.”

That sort of open-ended inquiry is something she believes in fervently. “It’s all about exploring the ideas,” she says. “My intentions have always been to speak out for those who feel marginalized…because I have felt that way as a woman, an artist, an African-American, and a creative. I’ve definitely felt those pressures, and so being an advocate for the marginalized is what I do with this platform. My role is to help change minds.”

Monáe isn’t necessarily set on trying to appeal to the mainstream. Instead, she wants to remind those on the outside that they can belong, if they want to. “As an artist, sometimes you get privilege, but you can make different decisions,” she says. “I try to make sure that if I’m partnering with Cover Girl, or a brand with a lot of money, that it can be of help to some girl growing up in the ghetto. I would like to use those platforms to say, ‘Hey! Embrace the things that make you unique, love yourself, and redefine what it means to be beautiful.'”

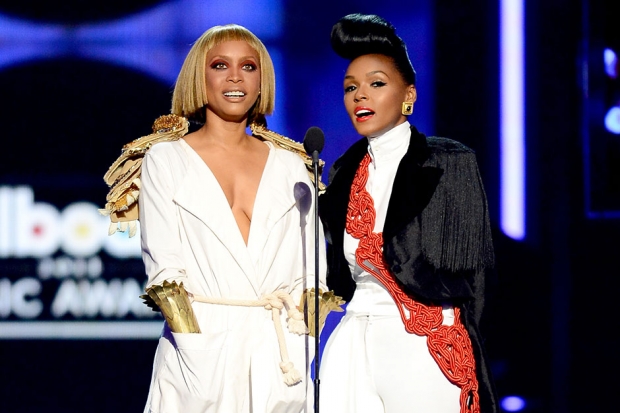

And so, in her Cover Girl spots and on the red carpet, she wears outfits that riff on menswear: sleek suits, high-neck blouses, capes, and structured hats. Meanwhile, her adherence to red lipstick is an eye-roll in the direction of those, like A$AP Rocky, who persist in trying to hem in black beauty.

It turns out that what’s unknowable? about Monáe is mostly that she lives up to being an anomaly: She’s a thinking person’s artist, dedicated to sonic and philosophical growth. “I like evolving,” she says. “I think that every experience, every place you’ve been put in life, has the opportunity to mold you and the person you are becoming. Janelle Monáe is just ahead of herself.”

There’s a wistful tone in her voice when she makes that last statement, as if it’s trying to keep up with her ever-changing third-person self. “I’m learning about myself, just like you are, every day,” she says. “I want to create music and feel like it’s fulfilling for me, but also for a lot of other people, because I’m considering their thoughts as I’m creating.”

The Electric Lady, named after a series of vibrant paintings Monáe created while on tour, feels more outward-looking than The ArchAndroid. “Dance Apocalyptic” borrows from airy Motown pop, Bo Diddley, and Juicy J’s “Bandz a Make Her Dance”; on the title track, she shares vocals with Solange Knowles, building on the sprawling psychedelia of The ArchAndroid‘s “Mushrooms & Roses.”

Still, “I did not set out to recreate that,” she notes. “I find that repetitive and boring and dishonest. This is about community. So as I’m asking myself about these issues, and ‘Cindi’ is going through these issues, I’m also putting them back to the community. And I also wanted to bring in a community of artists.” To that end, she called in Badu, Grammy-winning jazz bassist Esperanza Spalding, Miguel (for the sultry duet “Primetime”), and, in something of a coup, Prince, who features on “Givin Em What They Love.”

“I got a chance to produce my musical hero and my friend, Prince,” Monáe says, allowing herself some audible glee. “He doesn’t get on anybody’s album, so for him to do that is just an incredible dream. I still can’t believe it.” Then she immediately returns to her default flat affect. “But more than just working with him,” she intones. “I’m glad I got a chance to flex that producer’s muscle. It taught me a lot about working with artists and how it feels for other producers to work with me.”

Beyond the lofty ideals and bucket-list features, Monáe says that The Electric Lady also allowed her the chance to pursue her biggest, and perhaps simplest, goal: “I wanted to create one of the best R&B albums of the year.” That’s the most straightforward, unencumbered remark she utters during our conversation; although, as if trying to cover her emotional tracks, Monáe’s frankness quickly gives way to cheekiness: “I wanted to stretch, so I brought in symphonies and orchestras — and Prince.”