Aaron North eases his dirty silver truck onto Sunset Boulevard and tells me how this is going to go. “I don’t want to be interrogated,” he says on this mid-summer night, sliding into Hollywood traffic. “We’ll drive for a while, and I can just talk. Are you a rock’n’roll fan? I know so many stories. My head is full of that shit.”

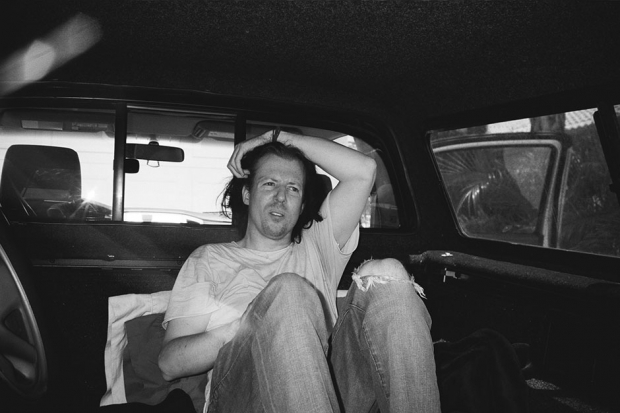

North, slight and pale, sits behind the wheel wearing jeans with holes at the knees and a t-shirt adorned with a Mount Rushmore of Communism: Lenin, Mao, Marx, Stalin, and Trotsky. His stringy hair is dyed black, like it was back in the early 2000s when he played guitar with a pack of rabid Hollywood wolves called the Icarus Line and then toured the world with Nine Inch Nails for a few years starting in 2005. Small red blotches dot his face, a reaction to the antidepressant Lamictal, one of a half-dozen or so such medications he’s on. He cracks his knuckles nervously at stoplights, plays his muddy Stooges bootleg CD loudly, and speaks in a ceaseless rush of words. It’s been a while since he had an audience.

“This over here,” he says in his trembling California-dude accent as we creep past an armpit of a bar, “that’s where Charles Bukowski used to drink. He’s one of my favorite writers — him and Henry Miller. I had a Kerouac phase after I quit music where I thought I was going to drive around and write all the time. See the back? See the carpeting? I figured I’d sleep in my car. I did that, but I never really did the Kerouac thing. I should’ve written three books by now and I haven’t finished one yet, so what’s the fucking point? That’s just how my brain works. Okay, we’re coming up to where David Bowie and Iggy Pop used to cruise for teenage girls. I’m obsessed with those kinds of facts. I can’t get enough of them. It’s like, ‘This is what happened.'”

North knows that undisputed facts are luxuries afforded the stable, sober, and dead. Over the last few years — to varying degrees of his own dismay — he’s struggled to achieve any of those three states.

We pass the Troubadour. “Great club,” he says, shifting into a higher gear. “I must’ve played there 50 or 60 times. I know a shit-ton about engineering and sound, and they do the sound right. It’s the way the speakers are set up. I saw [Greg Ginn’s revamped] Black Flag not that long ago. Not at the Troubadour, somewhere else. It was the first show I’d been to in I don’t know how long. Whoever their drummer is now is garbage.” North smacks out a pattern on the steering wheel. “That classic Black Flag fill — the guy couldn’t even do that. It was fucking pathetic.”

We turn on a side street and park down the block from a sagging apartment complex. North points to the curb. “John + Exene 1980” is scrawled in the concrete. A cop car stalks past the X co-founders’ former apartment. North scowls in return. “They’re busy trying to turn Hollywood into a middle-America, family-friendly Disneyland,” he says. “I’m a punk kid. I think when you clean something up, you kill it.”

We get back in the car, and North checks his cell phone. On the back is a homemade sticker: Shoot Pigs in the Face.

“The Starwood was there,” he says, nodding to a decrepit mini-mall. “That’s where the Germs played their last show. Darby Crash went from there to Oki-Dog” — a grubby hot dog stand catty-corner to the mall — “and then he OD’d. Wait. Fuck. Do I have my timeline right? The medication I’m on puts my head in a fog.”

We slink past a Jim Morrison party spot and a Henry Rollins pseudo-squat, past a church where the doomed Gun Club founder Jeffrey Lee Pierce posed for photos and a quiet apartment where Christian Death frontman Rozz Williams, American goth-rock’s guiding spirit, hanged himself.

“I know you’re not here to see this stuff,” says North. “I know that, dude. What do you wanna see? I haven’t talked about my life because I believe in taking the high road, not because I have something to hide.”

I ask if we can go see somewhere important to his story.

“We can do that — we can definitely do that,” he says, nodding. “Let’s cut deep. Let me show you where I went fucking nuts.”

“Aaron was the best, most entertaining guitar player I ever saw,” swears Queens of the Stone Age bassist Michael Shuman, who briefly played with North in the latter’s ill-fated post-NIN project, Jubilee. “He had this wildness to him onstage. He would scare you in a mind-blowing way. Everyone I knew in L.A. wanted to be in a band with him.”

And now? Shuman exhales deeply. “I honestly haven’t heard from him in forever. I don’t know if I want to get into it. We had some problems and then he sort of vanished. I hope he’s doing okay.”

By most standards, Aaron North is not doing okay. He’s 34 years old and, by his estimation, has the body of a seventysomething. When he looks in the mirror, he sees a “junkie-looking motherfucker” — despite, he says, having been straight-edge for a decade. In order to pay for his various medications, he draws the maximum amount of state welfare. He tells me that his treatment was a nightmare of incompetent doctors and labyrinthine bureaucracy, but now he feels like he’s finally found the right prescriptions. He uses an EBT card to buy food and attends group therapy multiple times a week.

Sometimes, North says, he sleeps at his mom or dad’s house. (His parents are divorced.) His grandmother is ill, so occasionally he goes to her home to help care for her. There was a period when some fans let him crash on their couch for a while, and he has a rental storage unit in Redlands, California, 70 miles east of Hollywood, where he keeps his musical gear, some of it still in road cases bearing the Nine Inch Nails logo. But the space has also doubled as a place to spend too many low and lonesome nights.

That is his situation, as he tells it, and it is actually far better than it once was. Up until about 18 months ago, when he hit upon a sustainable combination of medications and behavioral therapies for his bipolar disorder and severe depression, North had abandoned contact with nearly all his former best friends and musical partners. He has not played music in public since late 2008. His Internet presence petered out around 2011 — strange for someone who was a key contributor to a website, Buddyhead, that once drew millions of readers. His seclusion was so total that in the spring of 2012, an Icarus Line fan page posted an image of a milk carton with the words “Have You Seen Me?” written above the guitarist’s face. North, a sort of L.A. rock Zelig who counted Trent Reznor, Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme, and Tool’s Maynard James Keenan among his friends and collaborators, had been a beacon. Then he went dark.

“He was one of the only motherfuckers I saw when I first got into making music who was killing rock and raping roll,” says Eagles of Death Metal frontman Jesse Hughes, who means that as high praise and who, like so many others interviewed for this piece, warily counts himself as a “former” friend of North’s. “He had courage at a time in rock when it was real easy to talk big but demonstrate cowardice. He did unbelievable shit.”

Onstage with Icarus Line and later with Nine Inch Nails, North radiated a scarily intense charisma, stabbing his amplifiers with his instrument, spewing psychedelic guitar sleaze, and giving himself over to the thrilling don’t-give-a-fuckness that signals authenticity in rock’n’roll and a severe problem everywhere else.

“I saw Aaron push all his equipment off the front of a stage at an Icarus Line show in Silverlake,” says ex-Black Flag and Circle Jerks singer Keith Morris. “The band was told to get off the stage because they were playing too long … and there went his stuff. You never knew what Aaron might do. He was a star rock’n’roll crud.”

“You’d see Aaron smash guitars, and it seemed insane,” says former Icarus Line manager Les Borsai. “This was rock’n’roll — you never stopped to think that it actually might be insane.”

Aaron North’s youthful years follow the crusty, familiar contours of the Southern California rebel-rock script. Growing up in Black Flag territory in the South Bay cities of Hermosa Beach and Torrance, the son of an architect and a homemaker, North caught the disease when a friend of his uncle gave him some punk LPs.

“I became a super punk-rock kid at 14, 15,” he says, still driving as the sun sinks and Iggy Pop moans through the car speakers about feeling like dirt. “I was into Guns N’ Roses and Rage Against the Machine. I thought, ‘I can never play as good as Slash or Tom Morello.’ When I got Black Flag records, I was like, ‘You’re from where I’m from and your songs are all power chords. I can do that.'”

Like his punk heroes, North was not lacking for high-octane, anti-authority fuel. “All through high school, I was either getting jumped by kids who didn’t like the way I looked or getting beat by cops who should’ve been protecting me but still thought punks were some sort of criminal gang. It was constant harassment.”

So he did what lots of angry kids dream of doing, and burned shit down. Meaning he started actual fires. “It was just small stuff out where nobody lived,” North says, as we pull into a lot by a park near the last home he called his own. “But one of the fires got out of control and destroyed a guy’s trailer. I had to pay the damages. Every job I had in high school, the money went to paying this guy back. I was lucky I was still underage when I did it, so I didn’t go to jail. It was serious trouble.”

North doesn’t feel comfortable sitting and talking in the stationary car, so we get out and pace by an empty public basketball court. The outside air stinks strongly of weed, and two teenage boys at a park bench seem to find something seriously funny about their hamburgers. Beyond them, a police cruiser slowly traces the perimeter of the park.

I ask North when he realized there was something wrong with him, something that couldn’t be attributed to being a Black Flag fan in a white-flag world. “I would have these rages,” he says. “I remember one time in high school this teacher’s-pet motherfucker locked the classroom door on me five seconds before the tardy bell rang. I lost it. I smashed my hand through the classroom window. I felt like I was in the right, but I knew my reaction was not appropriate. I knew something was wrong with me. That’s the first manic episode I consciously remember having. But I just figured they’d eventually go away. I didn’t want to think there was something wrong with me, so I never tried to get help.”

North’s first real band, started when he was still a teenager, was called Gassex. “Little punk brats,” he calls it. After meeting fellow hellion Joe Cardamone, the two formed the more sordid Icarus Line in 1998. Vicious and rank and dressed all in black, the outfit released two independent albums before winning a deal with Virgin subsidiary V2, which released the band’s Penance Soiree, a minor classic of squalid confusion, in 2004.

“I signed them based on 11 minutes of death-trip music I heard on a demo,” says Jon Sidel, the V2 A&R man responsible for bringing the Icarus Line to the label. “Aaron and Joe were rebelling from the verse-chorus-verse-chorus songwriting that was on the radio. They were into anarchy. Dealing with them was like being in 1969 and having the Stooges walk into my office.”

The high (or low) point of the band’s performing career occurred at a 2002 gig in Austin, Texas. In the middle of a set at the Hard Rock Café during that year’s South by Southwest, North used his mike stand to smash a display case holding a guitar that once belonged to Texas blues legend Stevie Ray Vaughan. The incident was widely reported, the stories often depicting North as some sort of rock’n’roll black knight who’d pulled a magical sword from a phony corporate stone. “I wasn’t trying to liberate that guitar,” North says, cracking his knuckles again. “We were playing a show we didn’t want to play at a shitty club. People were spitting on us from the balcony. I snapped.”

//www.youtube.com/embed/BW1fBeqsn_s

He shakes his head. “Everyone said it was great. It wasn’t great. I had a meltdown, and I was championed for it. I was having a fucking manic moment in public. That’s why I did all those things I used to do: serious mental problems. But I kept thinking it would get better. I never told anyone what was wrong with me, so who knows what other people thought about why I behaved like a fucking maniac sometimes.”

Accordingly, the true nature of North’s behavior was hard for others to gauge. “We’d be in the studio, and there’d be a little technical problem, and Aaron’s pupils would go from little dots to grapefruits in seconds,” Sidel remembers. “He’d start shaking. We were like, ‘Calm down, it’s an easy fix.’ And he was like, ‘I can’t help myself.’ I thought it was perfectionism, you know?”

Though Icarus Line, who just released their sixth album, Slave Vows, were valorized for their Stooges-like ferocity, they also emulated the older band in a way that makes myths grow and money disappear. “They didn’t sell,” says Sidel. “Penance Soiree had all these accolades and sold, like, 17,000 copies. The band was just — this is when fucking Puddle of Mudd was popular, you know? They had their shot, and it didn’t work out.”

At the same time that the Icarus Line were whipping themselves into a frenzy onstage, North was doing the same to readers online via Buddyhead. Started by North pal and Idaho transplant Travis Keller in 1998, the byline-free site mercilessly skewered what it saw as a rock scene fat with talentless poseurs — and did so in a bombastically judgmental proto-Twitter tone. (“You’d have to smoke crack for this to sound good,” began one review of the Libertines’ 2004 self-titled debut.)

“There was so much bullshit in music, and no one was being honest about it, so we decided to speak up,” says North of the site’s mission. “Limp Bizkit were talentless assholes, so that’s what we said — over and over.”

Keller and North (the latter of whom quit the Icarus Line in 2005, and Buddyhead in 2008) were also fed salacious celebrity gossip: Who was fucking whom, using what, fighting when. And if confirmation was what you desired, the dirt often came attached with a phone number for the celebrity involved. This was good for attention — the site reportedly was earning as many as 12 million page views per month — and a steady source of income for lawyers.

“We were constantly getting cease-and-desist letters,” says Bryan Christner, Buddyhead’s attorney in those days. “I have a bunch from Courtney Love. I actually pulled out one of those not that long ago because I needed to see an example of a highly aggressive cease-and-desist. It’s a good thing that litigation is so expensive, otherwise they’d have gotten in a lot more trouble than they did. I helped them because I thought what they were doing was brilliant, and it’s a shame Aaron went away, because he was the one behind it with the pen full of poison.”

“The reality,” says Dillinger Escape Plan guitarist Ben Weinman, speaking on the phone from his home in New Jersey, “is that Aaron North is a hard person to believe.”

North and Weinman were close once, having become friends when the Icarus Line and Dillinger toured together. “When he joined Nine Inch Nails, it was the perfect scenario — it was like the good guys won,” Weinman recalls. “He never kissed ass to get somewhere. He didn’t drink or do drugs. He was this lone-wolf person who didn’t fit in anywhere but found really amazing creative outlets. But Nine Inch Nails didn’t work out. It made him obnoxious: ‘Yeah, I fuck models now — go piss off.’ He’ll blame his situation on this, that, or the other, but he’s not always telling a straight story. His resume alone should’ve allowed him to keep being in good bands. So why isn’t he? It can’t just be because he’s mentally ill. That doesn’t make sense.”

But how could it? North says that after signing up for NIN in ’05, he was squeezed by a relentless touring schedule, under pressure to be at his wildest night after night, frightened to tell others about the demons in his head. He claims he did not have any addiction problems, and that those with damaging things to say about him are interested in revisionist history or simply have incomplete knowledge. Painkillers were necessary at times — canceling shows was not an option — even if they would counteract what he calls his “crazy pills.” So maybe he wasn’t so nice to his old friends all the time? If that’s a punishable offense, just about every human who suddenly earns fame and money should be up against the wall.

“Aaron North is different things to different people,” says Buddyhead contributor Tom Apostolopoulos. “I never had a problem with him. I love him, but there was also a time when I couldn’t deal with the kinds of things he’d get involved in.”

Like what? “I’d rather not get into it. You should talk to Travis or Joe.”

I tried to, and was shut down. North’s two closest ex-colleagues —Buddyhead’s Keller and the Icarus Line’s Cardamone — refused to speak to me for this story, other than to express disgust over the various shady ways in which their former comrade caused them pain. They were clear, though, in sharing their belief that writing about North was a misguided waste of time. He’s a destructive force, they told me, and he shouldn’t be rewarded with attention.

Theirs was not an isolated reaction. Others would speak about North only on condition of anonymity. I was told that he skipped out on debts and spread hurtful lies, and that he was not a victim. I was told that he was a manipulator who prided himself on being clean while gobbling painkillers, then explained his actions by saying the pills were necessary in order to ease back pain caused by years of sacrificing his body onstage.

“I’m not an addict,” North counters, in response to these dirty whispers. “I’m quite sober, almost frighteningly so. I have been ‘drug free’ for years… Well, can someone who is bipolar and takes more meds than a 90-year-old dying of cancer consider themselves to be ‘drug free’?” He adds that “the struggles of med changes, med combinations, dosage alterations, therapy, and group therapy would all be an absurd waste of time if I was also abusing drugs.”

Still, suspicions persist. “I’d be careful about giving him the most empathetic possible understanding,” said a former running mate of North’s who wished to remain nameless. “Whatever situation he’s in now, I’m telling you right now that there is no fucking way that it’s possible he’s clean. Clean and sober is not merely being off of street-illegal drugs. When someone is telling you about how many medications they’re on or how suicidal they are, are they doing it because they really need help, or are they manipulating you and trying to get you to be sympathetic?”

North shields his eyes from the headlights of a cop car that’s driven into the park. A police officer with a thick mustache, wearing sunglasses at night, opens the passenger-side door and asks for ID.

“I’m just walking around,” says North. “Why would I have ID on me?”

“Why wouldn’t you?” asks the cop.

North says, “I’ve been in this park after hours 2,000 times.”

The cop cocks his head. “Why’s that?” He tells North to take his hands out of his pockets. “We’ve had a lot of drug problems in this park.”

“This is too funny,” says North. “I kinda need to know if walking in a park is a problem now.”

The cop collects North’s personal information and confers with his partner. “Get out of here,” he says.

North cuts across the park, moving in small, quick steps. He stops on a palm tree-lined sidewalk in front of a dull townhouse. A beetle scuttles by. “This is it,” he says. “This is where I freaked out. I lived on the second floor. I went two months at a time without leaving that place. I’d unlock the door and order food and just tell them to leave it at the bottom of the stairs because I couldn’t deal with seeing other people. That happened pretty much the year after I left Nine Inch Nails. That’s when I cracked.”

According to North, in 2005, longtime Nine Inch Nails co-producer Alan Moulder, who mixed Penance Soiree, recommended his services to Trent Reznor, who promptly made a phone call inviting the guitarist to rehearse for a spot in his live band.

“I get a message, and this guy says he’s Trent Reznor, and he wants me to play with him,” says North, peering up at his old apartment. “I was confused, and thought he was just talking about doing an interview with Buddyhead or something. So I emailed him back and was like, ‘You want me to be in your shitty fucking goth band?'”

He did. After one rehearsal, North was invited to join the NIN touring machine. “After the Icarus Line, I thought I needed something manageable,” says North, smiling ruefully, “and a tour with Nine Inch Nails seemed like it would be.”

From their perspective, North brought “a certain chaos to the band,” Reznor tells me now. “That live incarnation of Nine Inch Nails was an amazing, unpredictable thing. He helped make it that. I just don’t know that he was equipped to handle it in the long term.”

“Aaron brought pay-offs onstage to the band,” adds drummer Josh Freese, whose time in NIN overlapped with North’s. “He would trash his guitar or give it to someone in the crowd at the end of a show. Or he used to drag his cabinets into the security pit and throw them into the audience. We used to joke around and say, ‘We’re having an off night. Go ahead and trash some gear, Aaron.'”

But, adds Freese, “He’d go too far.”

North’s voice, already thin, recedes into a whisper as he shares an unintentional moment over the edge. “It was at a show in Wisconsin,” he says. “I know I didn’t do anything wrong on purpose. It’s too chaotic and loud onstage for the techs to see you or hear you if your microphone breaks. So there are these drop zones that you’re just supposed to drop the mike stand into, and someone would bring you another one. And this security guard is standing in the drop zone. The zones are marked with neon tape. People are told specifically not to stand in the drop zones because it’s dangerous. I just dropped it down.” He cracks his knuckles. “These are custom mike stands, and they’re fucking heavy. This security guard was standing there. The stand knocked him out. It scalped him. I felt so terrible. He sued me and the band [in 2006]. It got settled, but I was like, ‘I’m just getting worse.’ I wasn’t supposed to even be in the band that long. I’m six kinds of crazy, state-certified crazy. I couldn’t deal with it.”

Reznor also says that North’s offstage antics eventually began to mimic his onstage unpredictability. “He started behaving erratically. It got difficult to have him around. I was still somewhat newly sober at the time, and basically just went to my hotel room and closed the door after the shows, but later I learned that there was some stuff going on that maybe explained Aaron’s behavior.” He leaves it at that.

This notion of an explanation is problematic. Did Aaron North have a drug problem? He says he didn’t. Was he mentally ill? Clearly. But regardless of the cause, he was clearly suffering, and so were the people around him. “There was so much pressure,” he says, recalling the circumstances that led him to finally leave Nine Inch Nails in 2007. “I was picking the opening bands,” he claims. “I was making sure everything was going smoothly. I was trying to work on music with Trent. I had all this money that I didn’t know what to do with. There was the lawsuit. It was all too much for me. I didn’t have a drug problem; no one else knows what was happening with me. It was manic depression, manic episodes, and I feel terrible about them and the trouble they were causing. That’s why I left the band. You don’t just leave a band like that lightly. I’m still bummed about what happened with Nails. I have nothing bad to say about Trent Reznor. He’s a great guy. I’ve dealt with a lot of fucking assholes who used to be my friends. He was never an asshole.”

I ask if any of his old friends or admirers or bandmates have reached out to him lately, to see if he’s okay.

“You’d think so,” he says. “Wouldn’t you?”

“Aaron had this idea that we’d learn to be a band by playing a seven-week tour of the U.K.,” says bassist Shuman about Jubilee, the Brit-rock-influenced band North started after leaving Nine Inch Nails which released a couple EPs on Buddyhead’s record label. “It was the worst tour I ever did. We hit every small town you’ve never heard of. So much shit was going down in the middle of it with substance abuse, and you’re playing all these empty rooms in small towns. Our booking agent was like, ‘You don’t really want to do this.’ But we did it. Aaron demanded it because it’s what Oasis did or something. It was the dumbest thing ever. We all hated each other by the end.”

The broken band returned to play a disastrous Christmastime gig at the Hotel Café in Hollywood on December 21, 2008. North spent endless time tuning, and the set derailed. He calls it his “Syd Barrett meltdown.” Not long after, he stopped working on recording Jubilee music. He says he tried to play guitar a few times in the ensuing years, but medications had dulled his talent. “It’s like my hands were always too late for what my head was telling them to do,” he says.

Following the miserable holiday show, North disappeared into the apartment we’d stared at from the street. He says he stopped phoning his friends and didn’t return any calls. He stayed inside for months at a time, reading books about music. His money drained away. The entirety of the first Obama administration is a blank, he says. He was alone and he wanted to die.

The afternoon after our first meeting, North picks me up again outside my hotel. He’s brought me a paper bag full of Icarus Line albums, Jubilee singles, and Bob Dylan bootlegs that he’d burned for me after getting to wherever it was he stayed the night before. Wedged into the seat between us is a thick blue binder labeled “Dialectical Behavior Therapy.”

“A lot of it is fucking bullshit homework,” he says about his treatment as we drive once more on Sunset. “‘Radical forgiveness,’ what the fuck does that even mean?”

North wants to show me Wattles Park, where Nirvana filmed the video for “Come as You Are.” He turns on the Stooges and lets it loose.

“I should be dead,” he says. “I used to walk alone in Watts or South Central trying to pick fights with gang members to try and get killed. I’d think about walking into traffic all the time. Then I finally decided I’d kill myself by jumping off the bridge. I didn’t think anyone would be sad for me, because if they were sad, they should’ve been sad for me years before I actually did it. I was gonna jump from either the Golden Gate Bridge or the Vincent Thomas in San Pedro. The day I decided to do it, I was driving, and I got to the ramp and thought, ‘If I go north, I’ll jump off the Golden Gate, and if I go south, I’ll do it in San Pedro.’ Then I realized that the ramp is the same one I used to get on to go visit my mom in Cucamonga, and I didn’t do it. I still wanted to die, I just didn’t want my mom to deal with it.”

He slows down in front of a large white house. “That’s where one of the Pointer Sisters used to smoke crack,” he says.

We come to a stop beside a rolling green park perched on a steep slope. “A year and a half ago,” says North, getting out of the truck, “I thought, ‘Either I need to kill myself or do something about things.’ I don’t want to play music anymore. That lifestyle and those people — I can’t get involved. That’s why I’m working on a book about what’s happened to me. There shouldn’t be a stigma about mental illness. There’s like a macho thing against it, which is bullshit. And being on government assistance: I’m here, I’m doing it, it’s okay, fuckers. Maybe one person out there would benefit from reading that. It’s a reason to at least try.”

Wattles Park is full of joggers and dogs. A teenage couple is hugging tenderly on the gravel walkway beside where Kurt, Krist, and Dave glowered for the cameras.

“I’m not saying I’m more special than anyone else,” North says as we walk up a steep embankment. “My life was wild enough. Why would I make anything up? I never tried to tell anyone that I felt like I was being applauded for my mental illness. I never tried to tell anybody, because they’d never understand. I’d go on tour and run out of anti-depressants, and trying to kick that shit is harder than kicking heroin. I was in an impossible situation.”

North explains that he knows he’s let people down, that he’s caused pain and offense. He also says he’s been misunderstood.

“If I wanted to be a woe-is-me guy, I’d put it like this: I was good to people. I made good music. I feel terrible that people had to deal with my shit. I know people can’t forgive me for some of the things I put them through, and I know people have hateful feelings towards me. But I don’t want any fuckers feeling sorry for me. If I die, it’s okay, because I lived. I got to travel the world. I got to play music.”

A warm breeze whips North’s hair around into his face. Los Angeles sprawls below. He squints and looks south.

“That little curve out there, that’s where I’m from,” he says, pointing at a place far off in the distance, out where the smog touches the horizon in the fading summer light. “That’s the South Bay. Can you see it?”

I’m not sure. It’s hard to know.

“You just don’t recognize it,” says Aaron North, cracking his knuckles, then cracking them again. “It’s there.”