In early ’80s London, rock critic-vocalist Neil Tennant and architect-keyboardist Chris Lowe constructed a different, far more arch and playful life for themselves as the duo Pet Shop Boys. They were fascinated by the club scenes in their native U.K. and New York City, the latter of which was exploding with innovations from Latin Freestyle DJs and rising pop stars like Madonna. Those influences shaped their 1984 single “West End Girls” and seminal ’86 debut LP, Please, the beginnings of a career that has made them worldwide cult heroes, and more than an occasional mainstream success, for their commanding, intellectually teasing dance-pop.

The twosome’s latest full-length, Electric, lives up to those high standards. Produced by Stuart Price (Madonna, the Killers, Kylie Minogue, Scissor Sisters), the new effort is a startlingly contemporary record of massive beats, surging tempos, and euphoric, nasally crooned paeans to the power of sound. Speaking on the phone from London, Tennant, 58, shared with us the secrets for how these Boys have stayed fresh for more than 30 years.

Chris has said Electric is about rediscovering the joys of youth. What joys did you discover?

We first recorded in New York exactly 30 years ago, and we were listening to Latino dance music on the radio. I had a cassette of Madonna’s first album, because I was a journalist and I had an advance. We were listening to 92KTU on the radio, and it was a very powerful influence. Somehow, it’s all re-emerged on [Electric], and I don’t even know how. It wasn’t a deliberate strategy, but it seems to have some of that young flavor of New York in the early ’80s. Throughout the album, the music’s got a lot of space in it. If you listen to electronic dance music of the early ’80s period, like for instance, Madonna’s first album [1983’s Madonna] — there’s a lot of space in the music, too. It’s not filled up with samples and clever keyboard parts. [That era’s music] has a slightly naïve technological approach in that the synth-bass lines are probably played live, so the timing of the records is a little unsteady. If you listen to Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam’s [1985 single] “I Wonder if I Take You Home,” she’s singing totally out of tune, but there’s something really great about it.

What differentiates yourselves, Depeche Mode, and others from the reunion circuit?

Ourselves and Depeche Mode have never broken up, so when you don’t break up, you don’t get the great moment where you come back together again. [Laughs] You have the continual history, which I think is a testament to your integrity that you are doing this music because you want to do it and you love doing it, and you’re not just a sort of genre-hopper. You want to feel that the potential for new sounds and new songs is still possible for your new music. If Chris and I were just touring the songs from our first two or three albums, we would have given up and done something else. But the backbone of the Pet Shop Boys is that we love going to the studio and writing new songs. We do it for pleasure as much as anything else. It’s just a wonderful thing we share between the two of us, and that’s why we keep on doing it. Once we’re done [working on an album], we really want our album to be a huge, massive international hit, then we deal with the disappointment.

Is there any desire for the success of your 1986 to 1988 “Imperial Phase”?

You can grab [success] at certain parts, but I don’t think we ever did that. Success came to us, and we became a kind of huge cult band around the world. The Pet Shop Boys are a household name — in Britain and Europe, anyway. It’s a complicated thing, because is [success] even about music, really? Is it just about sex? Are the Rolling Stones still selling sex in their early seventies? I sort of think they are. Is Madonna still selling sex? I sort of think she is.

How has rock music in general shown up in your own music over the years?

When rock’n’roll is good, it’s really pop music. My favorite records by Bruce Springsteen are pop records: “Dancing in the Dark,” “Tunnel of Love,” Streets of Philadelphia.” I think the cover we’ve done of the Bruce Springsteen song [“The Last to Die”] on this album [Electric] makes it into a pop song. But we haven’t changed it any way at all. It’s just done in a pop style rather than his E Street Band style. We could do a lot of Bruce Springsteen — not that we will. They’re very powerfully written songs with good melodies and quite simple chord changes, more simple than our chord changes, so they take to the electronic treatment. Where I have a division from rock music is when it ceases to be about the excitement in the songwriting and it becomes about ego. But I also break with pop music when it becomes about ego, and there’s a lot of ego in pop music.

How do you guys differentiate between having a “style” and projecting ego?

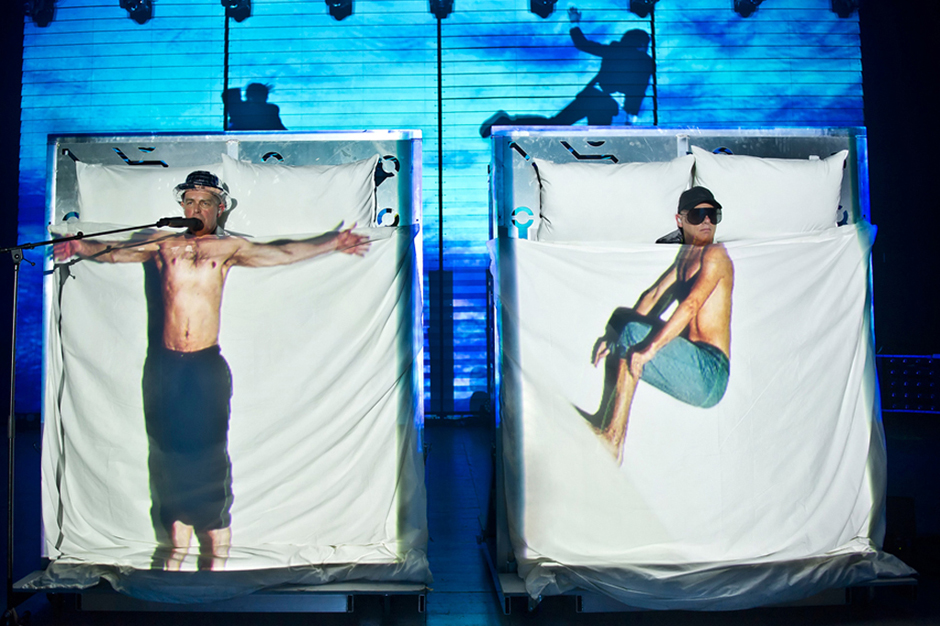

Well, we design the shows as a sort of whole. The idea is the music and the visuals become one experience. It’s normally a multimedia experience. There might be other performers on the stage as well and a lot of film. And this tour [that] we’re going to bring to the United States in September, it’s a very electronic, high-energy, hi-tech experience. Our last show was extremely theatrical, more colorful than this one. This one is dark and more electronic, but it’s got an incredible pulse and pace to it. It’s amazing, because it’s become a very conservative thing where people think it’s almost rude if performers perform new songs and that all the audience wants to hear is the hits. If I go see David Bowie, I don’t just want to hear “Jean Genie,” “Suffragette City” and “Let’s Dance.” I want to hear some weird tracks from Diamond Dogs. I want to hear some of side two of “Heroes”. We’ve applied that [attitude] to our show. You get “West End Girls” and “Always on My Mind” but you also get new songs, you get rediscovered songs like “I’m Not Scared.” The idea is to make a whole sweeping statement that encapsulates everything we’ve done.

How do you feel about how contemporyary R&B production has been emphasizing dance music?

The giant melting pot of contemporary pop, American and European, is interesting. It’s got house music, electronic music, electronic ’80s music, hip-hop, R&B, and it’s all being stirred around. Coldplay are friendly with Jay-Z and Beyoncé. There’s a lot of on-the-floor kind of records, which I find immensely tedious. But it is interesting: You get Snoop Dogg on what, to me, sounds like a Euro-cheese record. Actually, a lot of this music sounds to me to be very early-’90s. Rather than ’80s, it sounds very early-’90 — that period where we had sort of Euro-disco meets grunge. It was a tricky period.

Speaking of growing pains, have you met any of the babies from ’89’s “It’s Alright” video?

Oh, I’m always meeting them. In the last 18 months, I think three of the babies have come up to me. One was on the street. I think one was in an airport, maybe even on the same flight. And another one was in a club or something. Actually, one of the mothers of the babies came up to me and said, “My baby was in your video.” It was a really enjoyable video. It was in Notting Hill somewhere, and we got there, and all the babies were asleep — all the 50 babies. And then one of them cried [and] they all fucking woke up. It was Chris’ idea, that video. I still think it’s a very original idea, and it terms of the style, it was meant to be a tribute to Robert Mapplethorpe, the way it was lit in black-and-white.

So all the babies seem to be well-adjusted?

Oh yeah, they seem to be thriving. We should get them all together for a party. We could have a joint 30th birthday party for them.

Nearly 30 years ago, you dismissed the band’s initial accolades. Were you just being coy?

To be honest, we didn’t feel the slightest bit ambivalent about it. What we did was we never wanted to appear triumphant and become egotistical monsters and say, “Hey, we’re number one, pour the champagne.” Although inwardly, we probably felt a bit like that. [Laughs] I mean, it was sort of a ridiculous period in a way. A year after I left Smash Hits magazine, we were number one in America. [Laughs] It’s a tribute to American taste as well, I think.