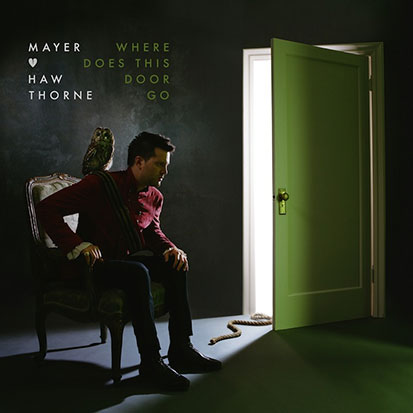

Soulster Mayer Hawthorne grew up Andrew Cohen in Ann Arbor, Michigan, not Detroit (his stage surname came from the street he was raised on), and he lives in L.A. now, but chances are that only makes him more determined to prove he’s carrying on a certain Motor City legacy. He pays tribute to Henry Ford and Berry Gordy in “A Long Time” on 2011’s How Do You Do, for instance, and references Highland Park and the long-gone Chrysler LeBaron on his new Where Does This Door Go.

Of course, Hawthorne’s main strategy along these lines has been trying to sing like he’s signed to Motown, which, on his first two albums, his decent falsetto and mid-register let him do better than most. As a white person, this initially seemed to link him to a tradition you could trace through any number of soul-history-conscious Detroit garage-rock revivalists all the way back to Mitch Ryder — even if Hawthorne was more likely to cite J. Dilla and Juan Atkins as inspirations; even if the door he came in through was the soul-history-conscious undie hip-hop label Stones Throw; and even if he’s generally opted for ladies’-man smooth over wild-man sweat.

On his new album, Hawthorne slicks up even further. His road band, the County, barely shows up; songs are shaped by a half-dozen, up-to-the-minute R&B/hip-hop/British-pop producers. And when the sound isn’t aiming to scale the charts Timberlake/Thicke-style, its “vintage” seems more ’80s than anything: Prince, quiet storm, the post-disco electro-funk retroactively called “boogie,” and — in tracks like “Allie Jones,” “The Stars Are Ours,” and sympathetic first single “Her Favorite Song” — a kind of vaguely West Indian, lightly funked semi-disco intermittently echoing Eddy Grant, ’80s Brit-soul group Linx, and Stevie Wonder’s “Master Blaster (Jammin’).” Which is to say, in two years, Hawthorne’s nostalgia has shot ahead ten years.

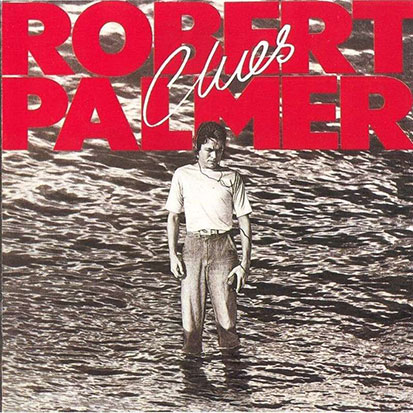

Meanwhile, he’s also establishing a rep as quite the snappy dresser. His suits and ties apparently read “nerd” to some (my friend Jill proclaimed him “the new Weezer”), but what I see, again, is a Romeo thing, from a guy whose first vinyl single looked like a red heart. Add the often conventionally model-like beauties who inevitably tend to wind up as eye candy in his videos, and seems to me that Hawthorne’s true well-tailored, reggae-flirting, chameleon-like, blue-eyed-soul precedent is one Robert Palmer — another dapper dan who managed to maintain just enough cool distance from his material to mask the surmountable limitations of his singing.

Also Read

8 Essential Doom Metal Bands

On Where Does This Door Go, Hawthorne ups the product-placement quotient, and one line Palmer might appreciate — given the apparently recently removed female undergarments strewn about on the covers of both 1976’s Some People Can Do What They Like and 1978’s Double Fun — is the lyrical advert for how Agent Provocateur is “accentuating your voluptuous curves.” That comes from Hawthorne’s Fatback-interpolating “Robot Love,” where he also asks not to be treated like a sex machine. He’s been known to cover Chromeo like Palmer was known to cover Chromeo role models the System, and on 1980’s eccentric Clues album Palmer fully embraced new-fangled technology, to the extent of interpreting some synthy Gary Numan future shock about being the “last electrician alive” and collaborating with Numan on another track. Palmer explained back then that he heard Numan’s “Cars” as “a soul song”: Interestingly, the same thing that Detroit techno innovators like Juan Atkins thought at the time.

And the Numan tracks were not even the most forward-looking blues clues on Clues. The two weirdest and hookiest were both singles, not to mention spare, anxious, herky-jerk new-wave moves promoted by outlandishly choreographed art videos for the new MTV crowd: the feather-falsettoed, xylophone-tricked, bouncing and clanging “Looking For Clues,” which opens the album worrying that whenever a phone rings horrible news will be on the other end; the ominously drifting, lower-registered, minor-keyed, hum-blurred “Johnny And Mary,” in which a depressively aging couple tire easily and lack a sense of proportion and need the whole world to confirm that they’re not lonely. Both songs charted in the U.K. — where Palmer was born and started his career playing Northern soul clubs, though he’d grown up the son of a boilermaker turned Navy intelligence officer in Malta, later settled in the Bahamas (where Clues and other LPs were recorded), then Switzerland, and in 2006 died of a heart attack in France. But where “Johnny And Mary” hit biggest was neurotic, robotic Germany, where post-krautrockers the Notwist would cover it ominously in 1994, when they were still too art-metal for indie fans.

Talking Heads’ Chris Frantz helps out bass-drum-wise in “Looking For Clues,” a month or so before Palmer helped out percussion-wise on Remain In Light, and “What Do You Care” has some frantic David Byrne nerves in its electro-funk, presaging blockbuster beats Palmer later took to the bank in “Addicted To Love” and the Power Station. It’s worth noting that Palmer’s interest in African music may have predated Byrne’s — he showed it off as early as “Off the Bone” in 1976, and it’s no doubt where Clues‘ “Woke Up Laughing” gets its off-kilter vocal cadence and wood-blockish rhythm. Heard now, the track also scans not far from the experiments that Arthur Russell was trying back then. Add two numbers featuring Free alumnus/”All Right Now” co-writer Andy Fraser on bass — beefy butt-rocker “Sulky Girl” and whipcracking Beatles remake “Not A Second Time” — and its clear that Palmer was dabbling all over a map found in nobody else’s glove compartment.

So, in some ways, of course, he and Mayer Hawthorne aren’t totally alike. They were born three decades and a couple of weeks apart, but where Hawthorne is now 34 and only on his third album, in 1980 Palmer was just 30 but already on his sixth, after four LPs fronting bands. His solo sets weren’t quite as retro as Hawthorne’s first two, either — the Meters and Little Feat’s Lowell George backed him on early ones, and some optimistic funkers almost could pass for the band War, but curiously for a late ’70s blue-eyed soulster he never really went disco. He wasn’t more than a couple years behind on Caribbean sounds, though, titling his 1975 album Pressure Drop after its Toots and the Maytals cover, for example.

Hawthorne’s sounding less backdated lately, though, so the gap is closing — especially as his proclivities turn more Anglophile with a Jessie Ware duet, and more global with Steve Mostyn’s Turkish saz opening a song where Kendrick Lamar big-ups Bob Marley. Still, what Palmer and Hawthorne most clearly share, on the surface, is a certain sense of style and fine taste in wine-glass women and upscale apartment shots and rare soul grooves. Palmer’s hair might’ve been more perfect. But Hawthorne’s could get there.

Robert Palmer – Looking For Clues by jpdc11