Tonight, on Halloween, hordes of us will do what humans have done for eons and herald the coming of the dark, cold months with a celebration. Though it’s been untold generations since our fall festivals were softened into a vestigial superstition, Halloween’s roots lie deeper than playing make-believe. They grow from our inborn compulsion to gain some measure of understanding, of control, about the things we spend the rest of the year trying to deny. Life is tenuous. Pain is constant. The world is frightening. These are ineluctable truths. And so is this: Black Sabbath matters.

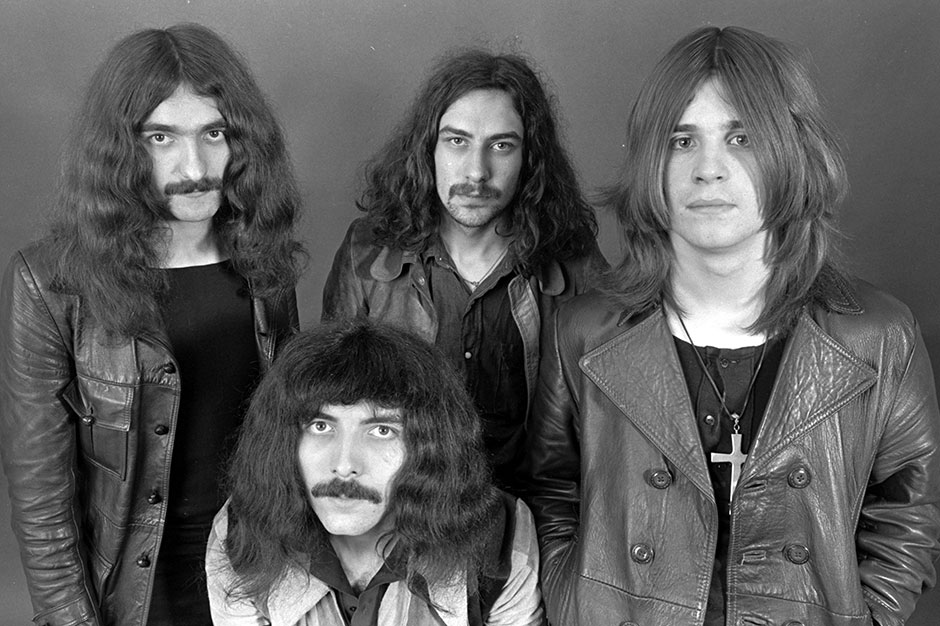

Black Sabbath was the first rock band to get over on trying to scare the shit out of you. Others (Led Zeppelin, Blue Cheer) were making sinister, heavy music before singer Ozzy Osbourne, guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler, and drummer Bill Ward got together in Birmingham, England in 1969. None of those other bands were as committed or singular in their bleak vision. From the start, Sabbath emitted no light. That was for others to do. The band’s self-titled first album was released in 1970. In sickly and unnatural colors its cover shows a witch-like figure in front of a desolate country house. The eponymous first song opens to whispering rain, a tolling bell, and a slow, creeping guitar riff. Then Ozzy enters. He sings as if he has no soul to lose. He could be the dead-eyed henchman in some Vincent Price movie. He could not wail virtuoso-style like Robert Plant or Ronnie James Dio. Instead, Ozzy sounded plainly human. Or as if he remembered what it was to be one.

After “Sabbath,” the first album descends even further. At times the music is bluesy; the rhythm section has a swing to it, which instantly makes Sabbath more memorable than 82 percent of all metal. Iommi plays some jazzy licks on “Warning.” But the mood is defined by the sepulchral gravity of his down-tuned guitar and Osbourne’s yob zombie vocals. The latter sings, “My name is Lucifer / Come take my hand,” as if he’s trying to convince himself, which is more disturbing for it. The album is the stuff of B-level horror films and Dennis Wheatley novels, of Ouija boards and idly drawn pentagrams. For myself, and millions more, it’s the necessary stuff of release. Others, including the band members themselves, have made connections between Birmingham’s bleakness and the music’s oppressive weight. Robert Christgau called the album “bullshit necromancy.” Better that than the real thing.

Black Sabbath’s musical appeal is self-evident: Riffs, hoodoo, rhythm. I listen to “Wheels of Confusion” today and I still feel the same excitement that I did when I heard “War Pigs” for the first time 15 years ago. Iommi could put more incredible riffs into a single song — it’s just, you’re listening and going: another one? Another one? ANOTHER ONE? Ward and Butler have that blues-bred groove. They lumber only when they choose to. Ozzy’s got that undead charisma. The music is nimble. It finds shades of black. It gives pleasure in a way that, say, a black-metal genius like Xasthur doesn’t. Xasthur is an emotional snuff film. Sabbath is Witchfinder General. Really, though, there’s no reading I can give of Black Sabbath’s music that is likely to change minds. Some people love haunted houses. Others don’t. Shadows give depth to the things in the light. That’s as good as I can do. That, and “Supernaut.”

And this too:

//www.youtube.com/embed/zxTKxFEhEBY

Listening to that makes the world more vivid, and maybe more honest. Smiles show fangs. Strangers hide plans. Generals gathered in black masses. The inherent criticism of Sabbath is that their music is shallow, simple fantasy, a toe-dip into true terror. While I have an unaccountably positive, psychosomatic reaction to the band’s particular emphasis on flatted notes and minor keys, I also have nightmares. I get scared. Black Sabbath doesn’t sound like a fantasy to me. They sound like a band that accepts anxiety and fear. They sound like a band that allows for every day to be what Halloween once was, back before we thought we put darkness on a leash.

There is no control. Tony Iommi has been battling cancer. The Osbournes dulled whatever lingering edge Ozzy may have had. It’s hard to predict what those two, along with Geezer Butler, will be able to conjure in whatever studio they’ve been working in with producer Rick Rubin. (For convoluted reasons, those three and Bill Ward are on bad terms.) Whatever material comes from the Rubin sessions — and it might be great, as the band’s live shows this year were, and their just-announced Australian shows next year likely will be — it can never be the Sabbath of 1971. That band has become a ghost that haunts the current band’s existence. That band has become the thing it was always meant to be.