He found it. Flat on his belly, his tiny feet fluttering beneath the couch in his father’s skylit home studio, Rory Mascis, four years old and three feet tall, is stretching to retrieve a miniature guitar. “Do you want to hear some songs?” he asks, his long brown hair alive with static as he stands. “Lou and I are going to play some songs.”

By “Lou,” he means Lou Barlow: bassist, bandmate, friend, and foil to his father, Dinosaur Jr. frontman Joseph “J” Mascis Jr. At the moment, Barlow is downstairs in the living room with an acoustic guitar, waiting alone beside a small amp that he’s readied for Rory’s baby Les Paul. It’s a dreary May afternoon and Mascis’ Amherst, Massachusetts, home is playing host to the Dinosaur Jr. crew as they tweak and approve the final mixes of I Bet on Sky, the trio’s third full-length offering since reuniting, unexpectedly, in 2005.

“Rory,” says Barlow, 46, as he settles into a vast sectional couch next to the younger Mascis. “Before we start, you get to introduce us. Like I showed you.” Rory shifts in his seat and giggles. “Hey people, thanks for coming to the show,” he says. “We’re the Bathroom People Toilet Team. This song’s called ‘Diarrhea Doctor.'” At Barlow’s behest, they count it off together.

“Diarrhea doctor,” Barlow growls, “put your butt in my faaaaaaace!” Rory squeals. Laughing too hard to strum or sing along, he buries his face in a pillow. “It’s so good,” he manages to say, coming up for air. “It really is,” Barlow says in agreement. “It makes you crazy, it’s so good.”

In the kitchen, the mood is far more sedate. The elder Mascis, 46, currently at war with the flu, sniffles at his laptop, clicking through pages of used amps on Craigslist and GearSlutz.com, as the rest of the family eddies carefully around him. The day before, he and his wife, Luisa, a tall, Berlin-born brunette, took Rory on a quick trip to Manhattan, where he and Dinosaur Jr. drummer, Emmett Jefferson “Murph” Murphy III, joined former Minutemen bassist Mike Watt onstage at Le Poisson Rouge for a set of Stooges covers that included guest appearances from friends (Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore) and fans (stoner folkie Kurt Vile). And though Luisa glows when she talks about the performance, her infamously taciturn husband barely reacts at all, even as Rory comes running into the room for a snack.

“He’s in that phase,” Luisa says of her son, “where he thinks anything to do with his butt is just hilarious.” As Murph, 47, and band manager Brian Schwartz observe nearby, laughing, producer John Agnello comes clattering down the stairs from the aforementioned top-floor studio, carrying freshly burned CDs with mixes ready to be heard. Just as they did with both 2007’s Beyond and 2009’s Farm, the Dino Jr. threesome have been working here with Agnello and engineer Justin Pizzoferato on and off since February, creating what Luisa warmly refers to as “another family” in the house. That the word “family” could be used to describe a band so legendarily dysfunctional may surprise those familiar with their mythos. But in starting their own families, and in embracing the pliability of the term, it seems they’ve learned to cohere and communicate as exactly that.

Mascis shuffles over to a stereo and pops in a purely instrumental version of a song he’s given the working title “Downtown.” For the next hour, he will stand motionless, awash in his own influential bath of distortion and effects, offering mostly inaudible edits anytime Agnello appears at his side. “Less treble on the guitar?” the latter asks. Mascis’ mouth opens slowly, the response lost in the noise. We listen again. When it’s finally done, “Downtown” will become “Pierce the Morning Rain,” home to the lyric from which I Bet on Sky takes its name. Both stronger than the two post-reunion records that preceded it and equal to the electrifying, mid-1980s run of albums which established their legend, I Bet on Sky offers further evidence that, together, against oft-repeated odds, Dinosaur Jr. have grown more compelling as they’ve grown up and older.

Along a bookshelf in the kitchen, Barlow silently examines a J Mascis bobblehead doll. “This house is great, Luisa,” he says of the Mascis’ white colonial, previously the childhood home of actress Uma Thurman, whose father Robert Thurman, a renowned Buddhist scholar, played host here to the Dalai Lama. “You know, after our last place burned down, I told J we had to get this house,” Luisa says. “The energy is so special, don’t you think? Do you remember our last house up here?” she asks, referring to “Bob’s Place,” another home studio in the area that Mascis lost to fire in 2003. “No,” says Barlow. “That was a dark period. No idea what you guys were doing.” Luisa seems to immediately regret asking the question.

The moment is this day’s most biting reminder of the storied past and stormy dynamic that Mascis and Barlow share. Though no words or glances are exchanged, the tension between them is palpable. As mixing winds down for the day, a sitter arrives to allow everyone a chance to have a rare dinner together. “Don’t go,” Rory begs us from the doorway, his voice shrinking.

“Why don’t you write some more songs?” Luisa asks him over her shoulder.

“I can’t do it alone,” he whines. “I can’t do it without Lou.”

It is, Mascis admits, “a weird story”: band splinters as it reaches its creative apogee, only to reform and improve decades later. But Dinosaur Jr.’s beginnings were also fairly benign. In 1984, the saturnine, then-stallion-haired, 17-year-old dentist’s son answered a flyer he saw posted at Main Street Records in nearby Northampton, Mass.; some likeminded kids in the area were looking to start a punk band. Deep Wound, the resulting hardcore outfit, found Mascis, a thunderous drummer, combining for the first time with Barlow, a shy, sensitive, Midwestern transplant living 30 miles away in working-class Westfield. Despite some regional success, and an appearance on a compilation, Bands That Could Be God, assembled by manager (and future Matador Records co-founder) Gerard Cosloy, the group dissolved within a year. In its wake, a foursome called Mogo formed, though it was quickly abandoned by Mascis, who started Dinosaur on the side without telling guitarist Charlie Nakajima. The resulting lineup boasted a chemistry that’s remained explosive nearly three decades later: Barlow on bass, Murph on drums, and Mascis up front on guitar.

Frustrated with his new instrument’s physical limitations, Mascis immediately began experimenting with various effects pedals and combinations of amps, arriving at an idiosyncratic and volcanic sound: punk made peace with the guitar solo, and his plaintiveness became another means to bludgeon. “When he was younger,” says Megan Jasper, a close friend and now vice president at Sub Pop Records, “J had some anger, like any punk rock kid. Usually, though, when a young person is angry, they tend to be really loud. And J wasn’t. He was only loud when he played music.”

And Dinosaur Jr. were notoriously loud. Through three formative records in three years, a road apprenticeship with Sonic Youth, and a place on the label of their decidedly modest dreams, SST, the trio became a titan of the American underground and Mascis an unlikely guitar hero. “He had this style of playing,” says Built to Spill frontman Doug Martsch, “like he didn’t really know how to play guitar. I know now that that’s not true at all, but it didn’t seem like any other guitar playing I had ever heard before. It was wilder. It was freer.”

“Placing violence in beautiful music is something I learned from their records,” says indie-folk luminary Will Oldham. “Dinosaur’s music has a concern and a fatalism, but an unyielding energy to it, as well. It’s like they’re hitting you with one fist and correcting you with the other hand, alternately. That’s a good kind of love, I think.” After hearing the band’s first two albums, Oldham sent Mascis a copy of his personal fanzine in the mail. In return, he received a one page, hand-written letter from Mascis. “It was all of these almost rudely sarcastic compliments,” Oldham remembers. “Just taking a piss, which was fine, but why send the letter? You can’t help but think that this guy is nice enough to take the time to write this letter. And even though he’s trying to be funny and mean, obviously, he has a desire to connect.”

Soloing is Mascis’ lifeblood. “That’s how I like to express myself,” he says. “Everything is just the build-up to the guitar solo.” He means this quite literally. Mascis rarely communicated with his bandmates verbally, exerting total, silent control over the songwriting process and the trio’s direction. By the time the band had completed 1988’s Bug, Barlow and Mascis had stopped speaking to each other entirely, years of passive aggression (and what Mascis calls “mental warfare”) spurring an increasingly talkative and reactive Barlow to finally crack.

During a show in December of 1989, he sabotaged a set by milking feedback during a song that didn’t call for it, taunting his bandmates all the while. It was Mascis who eventually responded, taking a swing with his guitar, and as Murph started to leave the stage, Barlow jumped up on the drum riser, in triumph, ecstatic for having finally provoked a response. Mascis asked Murphy to break the news that the band was breaking up, but a new bassist had already been hired and an Australian tour already booked. Barlow heard that news by way of MTV.

On July 27, 2012, at 4:47 p.m. PST, Lou Barlow tweets the following:

“i’m training my son to kick journalists in the balls on sight.. spin guy coming by tonight for a dino jr ‘fly on the wall’ piece”

I wouldn’t read that tweet until I reached the driveway of his house in Los Angeles’ Silverlake District, a gorgeous hilltop stucco whose front door is haloed by a nest of neon Bougainvillea. “My son, Hendrix,” Barlow says, “he told me earlier today, ‘There’s a bad man coming and I’m going to kick him with my soccer shoes.’ This is a horror movie I’m about to send you into.” Barlow, in sandals and torn jeans, is leaning against the wall outside his home’s side entrance as his wife, Kathleen, takes a break from preparing dinner.

Inside, Hendrix is nowhere to be found. But Murph, who is currently without a fixed address and has been living here for most of the year, emerges from his bedroom in a faded T-shirt and cargo shorts, a ball cap atop his cleanly shaven head. Kathleen is plenty familiar. “I had his dad at Smith,” she says of Murph’s father, who was a professor of African Studies at the famed all-women’s college in Northampton. It was as a student DJ at Smith’s radio station that she first learned of Barlow through a spectral Dinosaur Jr. song he wrote named “Poledo” (from 1987’s You’re Living All Over Me). A station interview blossomed into a long-term, often long-distance relationship.

“When I first met Lou,” she says, “I had to do all of the talking, especially when we were dealing with the outside world. He had never had to find an apartment on his own, or call the gas company to get service. I’ve always done that for him.” She squints to see him across the room. “He’s better now.”

“Yeah,” Murph says. “If we ever got a hotel, I’d have to go in because these guys couldn’t deal with just going up to the desk and asking for a room for the night. I could not understand that.”

Murph, who would continue to play in Dinosaur Jr. for another five years after Barlow’s departure, has long assumed the unenviable position of intermediary between his bandmates. “My parents were divorced when I was 14,” he says. “It was always, ‘I don’t know, ask your mother; I don’t know, ask your father.’ I had to mediate, and because J and Lou wouldn’t talk or communicate, it was very similar.”

“He’s here,” Barlow yells, pointing toward a much smaller version of himself standing on the other side of the sliding glass door, two small, dark eyes slightly obscured by a mess of brown, sun-streaked hair. “Get him, Hendrix! Get him!” After a long, hard stare, Hendrix, scurries back into the darkness of the living room, bumping his older sister, Hannelore, as he goes.

Before dinner, Hendrix throws a silent temper tantrum below the dining room table.

“Honey,” Kathleen says to her husband, as bacon hisses in the pan. “He’s kicking.”

Barlow, watching his son flail about on the ground, is reminded of Rory in that moment.

“He’s so awesome with Hendrix,” he says of the younger Mascis, staring. “I wonder if he will be like J. He’s so fascinated with what his dad does, with guitars and amps. I’ve found that little boys are so tactile. They’ve got chaotic energy, too, you know? They just channel it. They need to.”

After Barlow’s departure from Dinosaur Jr., he spent much of the ’90s channeling his anger into his songwriting for Sebadoh, a cassette-recording project that would become an influential, full-fledged studio and touring project throughout the course of the decade. But he remained haunted by the internecine dramas that both defined and galvanized Dinosaur’s early years, and by what he saw as a missed opportunity to break the ceiling that Nirvana smashed two years after he left.

“J saw that coming,” Murph says of Nevermind, recalling a moment just before that album’s release, when Nirvana handled opening duties on a slew of Dinosaur Jr. dates along the West Coast in support of 1991’s Green Mind, the band’s first major-label album and its first without Barlow. “In Tijuana, J comes up during their soundcheck and says, ‘These guys are going to change everything.’ He just kinda looked at me said, ‘Murph, you’re an idiot. Don’t you get it?’ And I said, ‘Get what?’ And he just shook his head and said, ‘Dude, this is going to change everything.'”

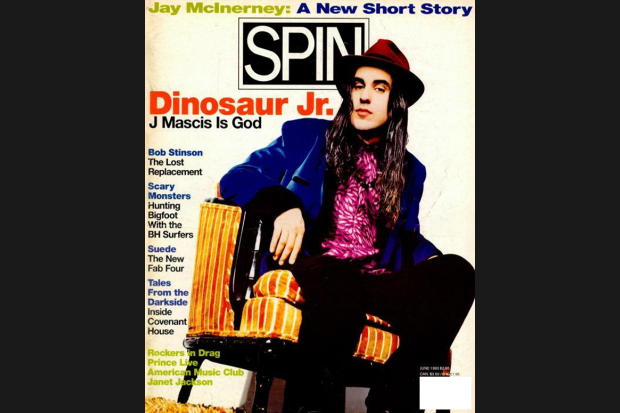

The alternative-rock wave that Nirvana unleashed helped Dinosaur Jr. enjoy a new level of visibility and commercial success. The majority of the roughly 1.2 million albums the band has sold can be attributed to its output during the 1990s. In 1993, their frontman would appear on the front of SPIN beside the cover line, “J Mascis Is God.”

“This is our ongoing conversation about what we do,” Barlow says, looking to Murph. “Yeah, J can do it without us, but Nirvana was an organic band. We had that thing, and lost that thing. If we had remained the original unit, our music was so angry we would have made it. Because when I was kicked out, the anger in the music subsided, it opened up.”

“But the dysfunction,” Murph says, interjecting. “It was just too great.”

“That’s the thing,” Barlow says. “You and I, we add that gnarl. When [J] liberated himself from the gnarl and what we had done, the music spread out. It became less…” He searches for the words. “It was beautiful, but Nirvana was still calling upon the gnarl. And we had that, but then I left.”

Murph, who has since struggled with addiction, and who Luisa calls “the beating heart” between his two bandmates, opted to leave the band after a disheartening run of dates on Lollapalooza’s main stage in 1994. “J was much more like a businessman back then,” Murph says of the time when the band’s leader was splitting time between New York and Amherst, recording every song’s part himself. “I’ve always thought that if he wasn’t playing music, he could be a Wall Street guy. It just felt like business. I showed up and learned my parts and played them. When he said to me, ‘If this isn’t fun anymore, you shouldn’t do this,’ my attitude was, ‘Man, this has never been fun. We aren’t a fun band.’ But we are now.” He takes a deep breath. “I still sometimes wonder, ‘How is this possible?’ But J and Lou have had kids, they’ve had to open up and they’ve had to learn how to communicate. It’s always a little awkward when the three of us are together, but we’ve just worked it out.”

While Barlow and Murphy began to reconnect during that time, the former’s relationship with Mascis remained tense. Barlow took jabs at his former bandmates in songs and in interviews, as well as from the stage after a Sebadoh show in Northampton on that outfit’s final tour in 1996. Mascis had come to show his support with friend and fellow guitar visionary, My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields. Barlow, drunk and incensed, began prowling the length of the stage, screaming at Mascis: “Me and Murph made you! We made you! Fuck you and your shitty attitude!”

“I was frothing at the mouth,” Barlow says, recalling the night. “I realized I had to make this gesture of anger, to the world, at that moment, with him there, even though I know he’s not processing it. I don’t care if it makes me seem crazy. I’m releasing those four years of just awfulness. I’m letting it go.” He pauses and looks to Murph. “And it was huge for me.”

After dinner, Barlow checks in on Hendrix’s bath. “How you interact with your kids is really fascinating,” he says, peeking in on Kathleen and his son. “My parents infused me with a lot of acceptance for the chaos of life, you know? There was an understanding that things happened. Life is not about whether or not you feel comfortable in every moment. It’s about stretching and working with people. They prepared me for that.”

In 2002, Barlow apologized to Mascis for the drunken outburst after the Sebadoh show. Together, the two shared vocals during a live performance in London of the Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” alongside Watt and original members Ron and Scott Asheton. Four years earlier, Mascis had been dropped from his label and retired the Dinosaur name altogether, opting to release a few solo albums under the name J Mascis and the Fog in the interim. But when Mascis began considering how best to reissue the band’s early catalog on CD in 2004, the demand for a reunion began to mount.

Barlow remembers the moment he brought Murphy into his L.A. practice space to play together for the first time in what had been 16 years. The first song they decided to play was “In a Jar,” from You’re Living All Over Me. “It’s totally ingrained,” Barlow says of his rhythmic connection with Murph, as Hendrix files out of the bathroom wrapped in a towel. “It’s ingrained on a level that neither he nor I could eliminate. No matter how many drugs we did in the meantime, no matter what happened to us. This is not an intellectual pursuit. We’re not deciding to do this on any level other than something completely intuitive, like riding a bike.”

Barlow speaks in explosions, punctuating his sentences with loud fits of laughter. You can see why a quiet type might find the earnestness and verbiage easy to resent. “You know, after Dino, I said, ‘If I’m ever in a band again, it will never be like this,'” he says, stretching in the hallway. “In the real world, you need to speak with people and you need to support it all together. You can’t make good music unless you communicate. But obviously, Dinosaur Jr. disproves that altogether, which is an amazing reason to be a part of it. I don’t understand it.” He shrugs.

“But that’s the thing about J: he’ll fucking show up,” Barlow says, continuing. “And that’s the reason why [we’re together]. He’s not like me, saying, ‘I’m not going to any goddamned Dinosaur Jr. show.’ He’ll go to a Sebadoh show. He’s still open-minded. I think the thing that brought me back to J was the idea that it’s all fucked up. People are fucked up.” He shakes his head. “If you have musical chemistry, it’s over. That’s it. If you can arrive on a common goal and focus on a song, that’s a miracle.”

The next day, that chemistry is on display at a video shoot in Hollywood for I Bet on Sky single “Watch the Corners,” with the three band members arranged at once and individually in front of a green screen over the course of three hours. There’s a little small talk here and there, but they never make as much sense in the same room together as they do when they’re in motion, when they play along with the track roaring back at them. The song itself is elephantine, a modern update on the white-knuckle melodicism that drove their early recordings. Barlow is barefoot, gesticulating with his bass until the strap comes loose. Murph is smiling. And then there’s Mascis, body inert, who looks as though he can’t feel anything but his fingers and face.

A month later, in late August, the Mascis family has just returned home after a two-week vacation on Cape Cod. Rory was allowed to bring along his friend Zach, who’s over today for a play date, wearing a green felt hat with eyes and teeth adhered to either side. He is, explains Luisa, a dinosaur. But due to a rash of great white attacks near Provincetown this summer, Rory and Zach are focused solely on sharks.

“Dad,” Rory asks his father at the kitchen table, “what do you do to sharks when they bite you? How will you kill them and stuff?”

“I don’t think you can, really.”

For the past 15 years, Mascis has become a devoted follower of Hindu humanitarian Mata Amritanandamayi, or AMMA, traveling with her around the world and even lending his musical talents to her hugging meditations at home and abroad. When Mascis and Luisa, who met in New York in the ’90s, decided to marry eight years ago, AMMA officiated at their marriage ceremony in Providence, Rhode Island. Portraits of AMMA from over the years are in every room of the house, as visible and numerous as the guitars and effects pedals that crowd most spaces and surfaces. There she is smiling in the studio and in Mascis’ study, looking down from windowsills in the kitchen and dining room. On the sunporch that extends into their spacious back yard, Mascis has hung a stained-glass painting of her name in the window.

“I was at my lowest,” Mascis says of the mid-’90s moment when he first discovered her teachings at an event in Boston. “As the band got bigger, I got more depressed. I was looking for anyone to help, to feel better. Doing anything else, I’m never sure if I’m wasting my time or not. But with [AMMA], I had a feeling I wasn’t.” Depressive since birth, Mascis says he was hit particularly hard by the death of his father in 1993 and the pressure to fill the void created by Nirvana, a band his friend Kurt Cobain once asked him to join.

“I think my voice is the main thing,” he says of the whine that’s distinguished Dinosaur’s music just as much as his guitar tones. “Kurt’s voice had that sound you’d heard on the radio when you were a kid: it was like Paul Rodgers [of Free and Bad Company] or Cheap Trick, that radio-friendly sound, that good rock voice. I didn’t have a voice like that. I sang out of necessity. But when you’re on a major label, then it becomes glaringly obvious. I even had our record-company guy say to me, ‘You should have the Oasis guy sing your songs.'” Mascis nods. “Another guy with a great voice.”

And as AMMA’s teachings helped him find peace creatively, they also helped him relate to those who cared for him. “At some point,” he says. “You decide, ‘Okay, I’m not going to kill myself. I guess I should try to feel better somehow.’” He stops talking and begins to drum the edge of the table with his fingers, humming. “I think I was in the womb, already trying to kill myself,” he continues. “I had the umbilical cord around my neck and I was upside down. I didn’t want to come out. I feel like that must be from a past life. I’ve always felt like a crotchety old guy yelling, ‘Get off my lawn.’ I’ve had that disposition, just walking around, my posture, my demeanor. But I don’t want to dwell as much. I don’t want to bring Rory down.”

Luisa has suggested that we take Rory for a bike ride to buy some groceries. In the garage, Mascis attaches a “Trail-A-Bike” extension to his seat, for Rory to ride behind him. We cycle down their street and across a main thoroughfare, past the Amherst College football stadium and crowded flower beds, onto a bike path stubbled and veined with moss. “Oh man,” Luisa says, as clean, fragrant winds push through cornfields and ferns on our left and right, through the tips of great elms above us. “I think a storm is coming.” Up ahead, Mascis pedals calmly, his hair streaming behind him like cobwebs.

We leave the bikes unlocked outside the main entrance of Whole Foods. Luisa buys a pound and a half of quivering Hake. Together, the three of us wheel through a battery of local cheese samplings, through the frozen-food aisles, Mascis moving slowly, looking right and left and then right again before turning the cart, in step with the dulcet tones of the cashier’s scanners. Keeping pace with him can have a strangely anesthetic effect. You can understand why it might unnerve someone more tightly wound. “The first time I saw J,” Luisa says as we try some juice samples, “Dino was performing in Berlin with the Gun Club. We wanted to stand right up next to the amplifiers, to get a real sonic feeling. The second time, he was in Berlin for Green Mind and my friend, she was promoting the concert. She said to me, ‘That J Mascis, I think he’s on drugs.’ ‘I don’t know,’ I told her. He just seemed kind of dazed.”

At home, we set the table in the sunroom after dark, and eat by candlelight. Luisa’s baked the fish and steamed some fresh chard. Mascis, who often wears thick, clear, safety goggle-like frames, has switched to a new pair of thin purple stems. He is otherwise preoccupied with his new cell-phone case, also purple, which deflects harmful radiation away from the body. His favorite color, purple, is everywhere here: purple paint on the house’s shutters and porches, a purple colander in the kitchen, purple panels on Rory’s soccer ball in the driveway, and a purple leash for the family bulldog, Mango.

Last night, Luisa says, she had a drink with the Mascis’ new neighbor down the street, Violet Clark, the wife of Pixies frontman Charles “Black Francis” Thompson. “She finds Amherst so quiet,” Luisa says. “It is,” Mascis murmurs above the crickets chattering in the trees. I ask Mascis if he’s had a chance to talk shop with Thompson yet. “That’s the one thing I’ve tried,” he says. “Guitars or amps or records or movies, it’s not really his thing.”

Reunions, Mascis claims, are another subject that hasn’t yet come up in conversation with Thompson. While the Pixies have yet to record a new album’s worth of material since they reunited in 2003, Dinosaur Jr. have equalled the output of their first try, and have now enjoyed a longer life the second time around.

“I had a big brother and he beat the crap out of me all the time,” Mascis says, barely touching his food. “He tortured me all through my childhood and I feel like I tortured Lou in some ways, too, just passing it on. But we grew up together and learned how to play together. I’m sure I’d be happier playing with other people, but I know Dinosaur’s got an original energy. It’s not like I was looking for friends. I had friends.”

I ask him if he considers Barlow and Murph like brothers.

“No,” he says, with a small laugh. “More like distant cousins.”