It’s hard not to find Sevier’s undiplomatic manner a little off-putting. There are points during the discussion with Smith’s family when I have to stifle my own instinct to jump in and smooth things over. The following day, when Sevier meets the former owner of a now-defunct record label, it’s all I can do to keep from kicking him under the table so he’ll stop staring at his laptop while the guy details his life’s work. But Numero’s no-bullshit approach has a purpose: They’ve got work to do and don’t want to waste anyone’s time.

Still, you can see why Sevier’s comments wouldn’t put Smith’s family at ease. Especially in the South, the music business is viewed with a certain historical distrust. And while it would be a vast oversimplification to say that the industry was built on entrepreneurs from the North swooping into southern towns to sign talent to wildly unfair contracts, that happened plenty and the emotional residue from that dynamic still exists. But more problematic for Numero is the so-called “reissue industry” as a whole, which covers a swath of companies, including glorified bootleggers who repackage old music without seeking any permission to do so or paying any royalties afterwards. Several Black Blood songs have turned up on these types of collections. Numero’s success, in part, can be attributed to the fact that they have a spotless reputation for scrupulousness.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=zXQF4ZBZNHI

Despite a few tense moments, the meeting hums along. Shipley and Sevier hold forth on some of Numero’s greatest triumphs — a four-CD/six-LP box set of songs by the once prominent but largely forgotten Chicago soulman Syl Johnson that was nominated for two Grammys and resurrected Johnson’s career; “You and Me,” a never-released demo by a group called Penny & the Quarters that Numero stuck on a compilation and led to the song’s prominent inclusion in the Ryan Gosling/Michelle Williams film Blue Valentine. They show off a prototype of their impressive-looking Eccentric Soul: Omnibus, a box of 45 reissued 45s that will come out in late October, complete with a 45,000-word book detailing the twisted stories behind each record and artist. Smith’s children talk expansively about their father, a dentist by trade. According to their accounts, he was a strong personality who was passionate about his music, politically active, and tough on his kids. They seem inclined to get this project off the ground.

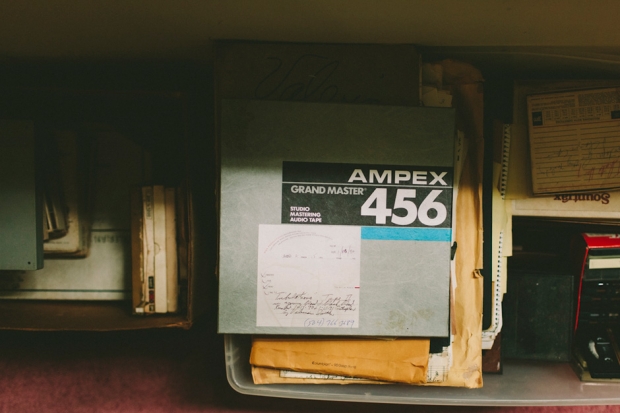

Eventually, two boxes of master tapes are brought out. Shipley digs through them a little, occasionally lifting a tape to his nose and sniffing it for mold, while Sevier methodically picks up each tape and writes down what’s on it, where it was recorded, and when. These boxes are only a small part of the cache: There are many additional ones in a walk-in closet toward the back of the house. The closet, Kim tells us, is where she used to go to smoke cigarettes in secret. About eight years ago, she tried to put one out in a napkin, which led to a fire. Fortunately, it was extinguished before reaching either the master tapes or the 12 canisters of butane stored behind them.

At a certain point, though, the mood of the meeting shifts, almost imperceptibly. Shipley asks if they can look at the other boxes of tapes to see what condition they’re in, but no one seems ready to show him. Shipley is unable to provide the family with any meaningful financial details about a potential deal because, as he puts it, “We don’t know what’s here. I don’t know if it’s a single CD, if it’s a box set — I really don’t know. There’s no point in me even looking through these tapes right now, because I’ve basically got to sort through and make piles. ‘Here’s 100 good songs. Here’s the 20 best of those 100.’ That could easily take a year.”

Also, there is concern over Sevier’s notebook.

“What’s he writing down?” the youngest sister Shawne asks.

Sevier explains that he’s taking information from the master tapes and keeping notes from the conversation that will help him to eventually shape liner notes for the project.

“I’d like to get a copy of that,” Shawne says.

“I’ll type it out; you’ll never read my handwriting in a million years,” answers Sevier.

“Well, we have a copier here,” she offers. Sevier again says he’ll type out the notes and send them to the family later.

There are murmurs around the room. Sevier’s reaction to the interest in his notebook seems to have amplified whatever anxieties had been lurking just under the surface of the meeting. Eventually, an uneasy truce is brokered. Someone takes an iPhone photo of Sevier’s notes. He promises to send a legible, typed copy once he gets in front of his computer. But the air in the room has changed.

When SPIN’s photographer tries to get the family to pose for a portrait after the meeting, they ask about signing releases and having approval over whatever photos might run. A vague plan for creating a “discovery document” to lay out a future course of action for the project is mentioned. But after the Smiths go back inside and we stand on the sidewalk next to the car, there are immediate doubts about whether the project really has a future.

“That got weird,” says Shipley.

Sevier motions to the car. “Let’s get the hell out of here.”