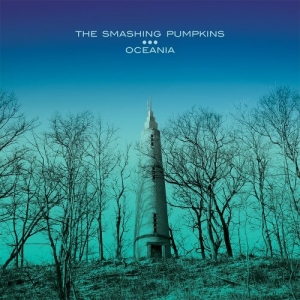

Release Date: June 19, 2012

Label: EMI

He was right about Pavement, y’know. Insufferable, self-righteous, whiny, and megalomaniacal as Billy Corgan can be, let’s give him that. It is possible to adore both bands and still regard the notorious, gratuitous Smashing Pumpkins diss on Pavement’s 1994 anti-hit “Range Life” — “I could really give a fuck,” it famously concludes, though the key phrase is the ambivalence of “I/they don’t have no function” — as cheap, snotty, class-bully-masquerading-as-class-clown cruelty, ambitious men who cynically refused to appear ambitious deriding an ambitious man whose band earnestly put out a double album called Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. Cheap, feigned-apathy posturing. A dick move. Clown verse, bro.

And Billy has never stopped bitching about it. About anything. For nearly 20 years. He’s gassed on about the usual, of course (the Great Pavement Reunion Cash-Grab of 2010 justifiably drove him nuts), but also Mudhoney, Arcade Fire, AutoTune, America (“We’ve lost our moral compass”), indie rock as an ethos, etc. The decades pass, the targets change. (Or don’t: See “I’ll fuckin’ piss on Radiohead.”) One unfortunate side effect of being on Corgan’s side is that you always hear him talking. As mastermind of the Alt-Rock Revolution’s most shameless, inelegant, unapologetically world-domination-seeking band, it was his exquisite misfortune to rise to power in an era when rising to power was regarded as gauche and embarrassing and possibly fatal, when cultural adulation became a horrible side effect instead of the Whole Point, when fame and success might very well drive you to suicide, or at least a ukulele-based solo album.

No, our Billy was a rock star uncool enough to actually want to be a rock star — uncool enough to think he deserved it — back when being uncool wasn’t cool either. Prime Smashing Pumpkins reveled in the alleged worst aspects of the ’70s (the excess, the prog, the squeedly-deedly-doo guitar solos) and has nonetheless aged splendidly: Siamese Dream is a shitload less dated than, say, Ten; and Mellon Collie, for all its blatant absurdity, is an astoundingly deep, committed, multifaceted, entrancing clusterfuck that is way closer to being the best record of the grunge era than any of us should be comfortable with. Don’t tell him that, of course, or let him tell you.

The comedown has been unpleasant. Our hero took the failure of 1998’s vaguely industrial Adore personally, of course — “I’m disappointed with our fans,” is a thing Billy Corgan said, into a microphone, to Howard Stern — and has struggled thereafter, shedding long-suffering bandmates like befouled layers of flannel (mind those horses, D’Arcy), vying in vain for a comeback, most recently with 2007’s rote, joyless, hilariously titled Zeitgeist. Now we greet Oceania, a new record with a new band that’s easily his best work since his rat-in-a-cage heyday, calm and confident and warm (everything his sound bites are decidedly not), redolent with arena-wimp grandiosity, evoking his greatest hits without getting caught up in the futility of trying to top them. A pleasant surprise, a palpable relief. To expect more from a Smashing Pumpkins record in 2012 is to wildly misunderstand the situation. That, we have come to find, is Billy Corgan’s job.

Not promisingly, Oceania is an “album within an album,” a subset of a much larger, stranger, plainly foundering, nonetheless allegedly ongoing 44-track piecemeal project called Teargarden by Kaleidyscope, whose early tepid reception on social media led Corgan to the conclusion that People Still Like Albums; which, okay, yeah, let’s stop to acknowledge the fact Billy Corgan is a man prone to public befuddlement that a diffuse, confusingly structured opus entitled Teargarden by Kaleidyscope has failed to resonate with the listening public. This, then, is his riposte. He’s made it clear that Oceania is to be an immersive, album-length experience unconcerned with the crass frivolity of hit singles, which is what people say when they are no longer generating hit singles.

And yet. The specific glory Oceania aims to recapture is obvious from the onset: The whisper-to-a-snarl King Kong surliness of opener “Quasar” mirrors the “Cherub Rock” trajectory exactly, the digital crunch of that classic Wall of Guitars grating pleasingly against the analog flowing-locks-in-wind-machine virility of the soloing, Corgan bleating robustly o’er top, as he does, trying out some Hare Krishna chants: “Yod he vav hey om,” he seems to conclude. A fine start. “The Celestials” shifts fluidly from the forlorn acoustic plaints of “Disarm” to the ice-cream-truck-rattling mega-chorus of “Today,” withstanding the corny vow, “I’m gonna love you / 101 percent,” which any decent college football coach will insist is at least nine percent short. For pure nostalgia, your best bet is probably “Chimera,” a cheerful, unencumbered riff-rocker in the tradition of “Rocket,” forever an underrated Corgan look, wherein he knocks off the long-winded topographic oceans shit and is simply content to write out four minutes’ worth of kick-ass Guitar World tablature.

The topographic oceans shit actually does okay here, though, and for that we must hesitantly nod to the new guys. Right or wrong, we have been trained by the man himself to dismiss Billy’s various fellow Pumpkins as largely superfluous and unhelpful and possibly entirely inaudible, hired-gun line-regurgitators with zero creative input, at best (mere promo-photo variety, at worst). It is thus with initial trepidation and irony that we meet Mike Byrne (drums), Jeff Schroeder (guitar), and Nicole Fiorentino (bass/vox), but given Oceania‘s heft and team-player cohesion, these people would actually seem to exist — to matter. If you buy into the immersive-full-album-experience concept, you have them to thank.

Byrne, who is, like, 12, and was apparently kidnapped from a Sam Ash mid-drum roll, is the easiest to isolate, of course; the impressive, tom-heavy rumble of “Panopticon” quickly asserts his lithe, explosive, decidedly Jimmy Chamberlain-esque ferocity, a deft balance of muscle and sinew. Schroeder presumably sneaked a few hot guitar lixxx in here somewhere. But Fiorentino is the revelation, her bass lines melodic and agitated and reassuring; listen to her prowl nimbly through the somber “Pale Horse,” reigning in the slightly overwrought mellon collie while subtly adding to it, her similarly unassuming backing vocals both softening and sharpening the sting as Corgan moans “Thorazine / Thorazine / Thorazine.”

And so when it’s time for the nine-minute, multi-suite title track that gets way out of hand, these young bucks at the very least keep up, rein Corgan in, keep him honest. (If Schroeder’s responsible for the skronking, “Maggot Brain”-yearning anti-solo that fades it out, then good for him.) As for Corgan himself, you’re either on board with his pained yap at this point or you ain’t. He’s a corny lyricist by default — “Rise! Love is here!” “Breathe! Love is air! There is a sun that shines in me.” “My love is winter / My love is gone.” “I’m not here to hold your hand / I’m just here to understand.” “Sweet baby, nurture me / Sweet lady, if you please.” (Pass.) “I used to know what a wish was for.” (A date with Tila Tequila.) And so forth. This is a man who has published a book of poetry. It was a confusing time.

But wait, Jesus, I’m sorry: 1,200 words about Billy Corgan, many of them unnecessarily sassy! Look: The eye-rollers come fast and furious here, lyrically and otherwise — always have, always will — but there’s a sweetness, a naïveté, a puppy-dog earnestness to his on-record persona that’s far preferable to the blowhard-on-stilts intolerability of his on-the-record persona. “You don’t deserve me, but I deserve you” is the ultimate quasi-messianic howler of a Billy Corgan line; if he said that on Howard Stern, he’d be buried in hoots of derision. But sung with what passes for “soulful” (for Corgan) in the midst of the lovely rainbow-in-curved-air-style electronic frippery of “Pinwheels,” he convinces you to keep giving a fuck, to concede that he does, in fact, have a function.