“He had a really fast downward spiral.”

HENDERSON, NV — Roughly a month before 18-year-old Las Vegas–area swim champ Jay Sirat was found asphyxiated in the garage of his suburban home, he penned a love letter to bath salts while checked into a Utah rehab center:

“You make me feel ready for anything. I love the way I can bump you just about anywhere. When I was with you, no one could control me. You made me tingle with each experience. When you hit me, I just started losing my mind. You made it easy for me to pass drug tests and still feel buzzed. I love you all and with all my heart and thank you for always being there for me, in every way and every situation.”

It was the afternoon of March 25, 2011, when Jay’s sister, Brittany, came home from work and went to her bed-ridden grandmother’s room. A couple of hours before, her grandmother had asked Jay to bring her some peaches, but he never returned. Brittany says she first thought Jay had just spaced out. On the kitchen table she saw an unopened can of peaches, a can opener, and an empty bowl. After a half hour and a couple of unanswered calls to Jay’s cellphone, a worried Brittany went into the garage. She saw Jay’s phone vibrating on a tool bench, plugged into a charger. Jay was slumped forward, in front of an exercise machine, with electrical cord wrapped around his throat. She thought he was playing a gag on her. Then she noticed his feet were not touching the floor.

“Jay was at the beginning of the salts wave; they absolutely contributed to his death,” says Alisa Sirat, Jay’s mother. Alisa and her husband, Robb, are sitting on the lawn outside a community swimming complex in this Vegas suburb, where Jay helped lead the high school swim team. Today, Jay’s 14-year-old brother, Troy, is competing in his place as an homage. “He had a really fast downward spiral,” says Alisa. “And it was fueled by daily trips to head shops to buy bath salts.”

Things weren’t supposed to go this way for Jay. The Sirat family is solidly middle-class and active in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Robert is an industrial components salesman. Alisa is a teacher. Their home and their neighborhood are well-manicured and seemingly untroubled.

But Jay began his distressing drift at the end of his sophomore year in high school. Recruiters from colleges such as Cornell started scouting him for their swim teams. Eventually, more than two-dozen fat envelopes arrived at the Sirat home addressed to Jay. Alisa thinks it might have been this excessive attention that freaked her son out. He started to party and get cocky. Then, the summer before senior year, Jay got busted for driving under the influence of weed and Ecstasy. He was placed on probation for a year with monthly drug tests. His grades started slipping and he wound up not applying to any colleges. When his mates on the swim team all graduated and moved on, he was left behind.

Even though Jay was regularly coming up clean on his court-ordered drug tests, his parents saw him becoming more erratic. “Not just adolescent moodiness, it was beyond that,” says Alisa.

One night, about five months before his death, Jay got into a fight with his dad because he wanted to sleep on the trampoline in the backyard. Jay stormed out and said he would stay with his girlfriend. Once the girlfriend picked him up, they began to fight, and Jay threw himself out of the moving car. When his father went to help, he found Jay shirtless, screaming, and throwing rocks at him. “He was so angry, he seemed possessed,” Robb recalls.

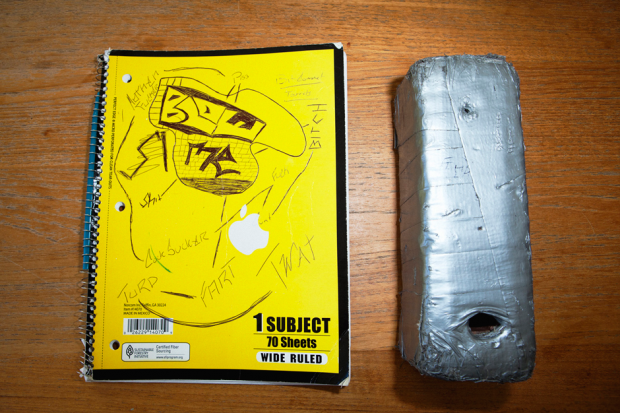

Things started disappearing from the Sirat house — electronics, jewelry, Jay’s parents’ wedding rings (Alisa found hers in a local pawn shop and bought it back). His parents were certain that Jay was using, but were confounded by the way he continued to come up clean on his monthly drug tests. When Jay disappeared one night, his parents searched for him all night and found him early the next morning, curled up by a Dumpster in the parking lot of a local school.

When Jay posted “I should end it all” on Facebook, his parents were able to get him temporarily committed to a psych hospital. By emptying their bank accounts, looking under couch cushions, and rolling up loose change, the Sirats put together $20,000 to send Jay to Renaissance Ranch, a Mormon-affiliated rehab facility in Utah.

While Jay was in Utah, Alisa combed through his room. She found dozens of foil packets with powdery residue inside. She went through his pile of unwashed laundry and found receipts from a head shop called Jungle Zone in nearby Summerlin. Alisa drove to the store, which was a few blocks away from a practice pool where Jay would often swim. Inside the Jungle Zone, she saw a five-shelf display by the counter; Alisa recognized the foil packets inside the display case.

She checked Jay’s bank statements and discovered that he was making daily trips to the Zone and a couple of other local head shops. Alisa and Robb told Jay’s probation officer, as well as his counselors in Utah. “I said, ‘Look, this is the stuff he’s on,’ Alisa says. “They treated me like I had a third eye in the middle of my head.”

Robb called a doctor to ask about the effects of bath salts. “I might as well have said I was Abraham Lincoln and I was drumming for Bon Jovi,” he laments. Bath salts and their consequences remain a mystery to the wider rehab and law enforcement community, let alone public consciousness.

Jay made it to 30 days clean and sober at Renaissance Ranch. He wrote extensively in his journal, attended meetings, and regularly called his girlfriend. But it was all for naught. After moving into a sober-living house with a sketchy reputation, Jay started using heroin and overdosed. He was revived in the ER with nitroglycerin and drove home to Las Vegas the next day. When his parents picked him up, he told them, “If I stay here, I’m going to die here.” One week later, Jay was dead.

“I know it sounds odd,” Alisa says, “but there have been a lot of good things that have come from his passing.” Not only did a half-dozen of Jay’s friends quit drugs because of his death, but the Sirat family started a public petition campaign on change.org to have bath salts outlawed. That drive contributed to the public clamor that has led to the current ban.

Alisa and Robb don’t think Jay killed himself. They believe Jay was so desperate after a year of snorting bath salts, taking Ecstasy, and smoking Spice that he wanted a fix but did not want to use drugs anymore. “The coroner reported a very slight amount of Ecstasy was in his system,” Alisa says. “But at the time, they didn’t know to test for bath salts.”

Perhaps, Jay was trying to choke himself and create a natural high of adrenaline. He had recently promised his swim friends that he wasn’t going to use drugs again. Alisa thinks Jay may have been trying to keep a promise, but she can’t be sure. And her uncertainty mirrors that of every police officer, DEA chemist, and user. Alisa tucks strands of her hair behind her ear, as cheering from the backyard fills the silence.

“Who knows? That’s the thing.”