You Know How It Is

Legend has it that Adam Horovitz once said he knew he would be famous from the day he was born.

Certainly he has the confidence that breeds charisma. “What are you gonna say that I don’t know already?” he asks in “Pass the Mic,” adding that “I’m like Clyde, I like to rock it steady.” (Rockin’ Steady is the name of the biography of former New York Knick Walt “Clyde” Frazier.)

I wasn’t gonna tell this guy anything he didn’t know already. Like Alexander, he’d conquered the world before he was 21. Then he’d romanced several Hollywood hussies before settling on his true love, actress Ione Skye. As Horovitz likes to say, You know how it is.

Actually you and I don’t. Which is why Ad-Rock is a hero to kids of all races and classes — from actor and oil heir Balthazar Getty to the scores of middle-American teens who still call the number found on Paul’s Boutique. He’s living out our fantasy. “I got it made,” he says without gloating. “I’m the luckiest kid in the fuckin’ world. I love it. I love it.”

On a typical day he’ll meet for breakfast with Skye, their friend actor Max Perlich, and whichever other Hollywood kids show up. After eating on Sunset, we go next door to the record store, but Horovitz has most of them already. “You’re not buying a zydeco album, are you?” he teases Perlich.

He shows me his backyard playroom, where there’s an eight-track tape player, ramshackle drum kit, and portrait of Mush Mouth. In his bedroom, we watch a video about reggae featuring the Gladiators. “Listen to that voice,” he says with unexpected and disarming sincerity.” I watch this tape fuckin’ every day.”

We drive to a café, and I say that Kate Schellenbach remembers how, when they were teenagers, Horovitz would “stop to call his girlfriend at every phone booth.”

He also ran up enormous phone bills after he met Molly Ringwald on the Licensed to Ill tour. He and Ringwald also went to Ireland to track down their roots (Horovitz’s mother was Irish). And even though he couldn’t drive, he went to L.A. and lived in the valley. “That should tell you what I’m like,” he admits. It should also tell you why he had ulcers.

What’s more, according to Horovitz, he met Skye when he was still going out with Ringwald. “So I stayed out here and waited until I could go out with her. Kinda secretly.”

At the café, Horovitz asks the waitress to turn down a power ballad simpering from the speakers. “I hate this shit — Michael Bolton. They just take everything, and don’t give anything back.”

This reminds me of “Gratitude,” where Horovitz sings like a rock star, “When you’ve got so much to say, it’s called gratitude.” There are not a lot of words on the new Beasties album, not because the band has nothing to say but because it has too much to say.

“It’s, like — ” he says. Silence.” That’s what. If I had to say something, it would be ‘Lighten up. Be cool.’ There’s just so many buffoons out there.”

Still, Ad-Rock unnecessarily downplays his quite flavorful guitar playing. And I wonder if his reluctance to do vocals isn’t the result of chickening out on being the front man he’s so obviously fated to be. “No, Yauch is James Dean,” he says, already retreating. “I can’t sing. I like being in a band.” Looking away, he adds, “I like Mike D. We kept trying to get him to go solo. He wouldn’t do it.”

Je Suis Music

There’s something about Mike D. He’s everybody’s favorite Beastie — even the other two Beasties’ favorite Beastie. After all these years, they still can’t help saying his name — “Mike D!” — with the utmost glee. The others helped create the look of a white kid pimp wearing a Volkswagen hood ornament. But when Rick Rubin suggested that they could do without Mike D, that was the beginning of the end. For Rubin.

Mike D is certainly in charge of his own shit nowadays. As he says in “Finger Lickin’ Good,” “[I’ve] got a million ideas I ain’t even rocked.” Diamond is the group’s spokesman, a liaison between the band and a world of squares. He deals with the press, accountants, promoters. His fax and car phone, in other words, aren’t just props. While the others rent houses, Mike D owns “Club D,” a Spanish villa with custom pool, subzero fridge, the works. His girlfriend, Tamra, is slightly older and has already been married. He has part interest in a hip clothing store called X-Large, where he sells the T-shirts he manufactures. The band’s lawyer, Ken Anderson, says that Mike D will have his own label someday. Business, however, never gets in the way of pleasure.

“Basically, all there is — is music. Records. Beats. New shit. And learning.” Already solid as drummer, he has the potential to be a Steve Gadd — type studio pro. He isn’t just into music. He is music. Indeed, on the back of his favorite baseball cap is stitched the phrase coined by disco legend Cerrone: JE SUIS MUSIC.

“I grew up totally on the alternative shit,” he says. “I came to the rock shit later. The opposite of how you grew up. I figured if most kids in high school were gonna smoke pot and listen to Zeppelin, then fuck that.”

Mike D worries today’s kids don’t feel as strongly about music as when he and I grew up — when the difference between punk and pothead was a big deal. “I hated Zeppelin then. It wasn’t the music, it was more like culture.”

As Jill Cunniff points out, the club-kid culture she and Mike D soaked up as prepubescent punks in the late ’70s was a very urban, liberal, sophisticated ideal. Before the jocks jumped on the hardcore bandwagon, the scene was a godsend for misfits and nerds. In the streets, Mike D, Cunniff, Schellenbach, Yauch, original Beasties guitarist John Berry, and others, played hide and seek and clobbered each other with giant cardboard tubes. Once inside, they’d hold hands in a circle and scowl at clods who stumbled onto their turf.

As different as this was from my own boilerplate suburban background, Mike D and I have somehow met halfway after all these years. While he now smokes herb and listens to jazz fusion, I now give hardcore the time of day. “So what you’re saying is that we’ve become Genesis,” he says.

Mike D knows me too well. But I press him, and eventually he concedes one point: “Our picture of a person listening to our album is somebody buying the vinyl, looking at the artwork, smoking a joint, putting on the headphones, and listening to it. Which I guess is a classic-rock concept, in a way.”

“In a very big way,” I add. “That’s precisely the image that punk reacted against.”

“Yeah, that’s true.”

Actually, it was only half true. As an incorrigible Led-head, I wanted to say that Check Your Head was the best prog rock album since Physical Graffiti. But I had to admit that, in fact, it’s the best punk rock joint since London Calling. I had been vindicated, but it was the Beastie Boys who had triumphed.

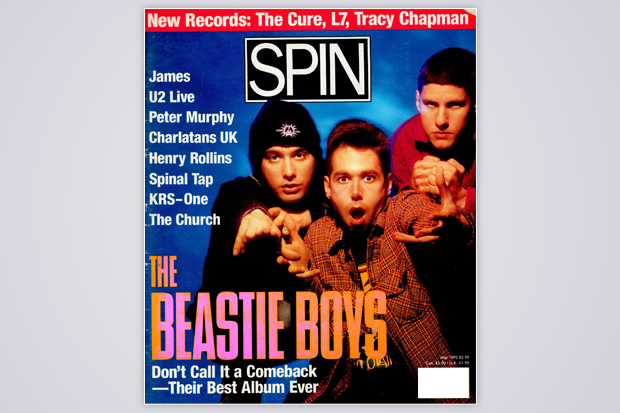

This story originally ran in the May 1992 issue of SPIN.